Skip to comments.

Scientists Warn Asteroid YR4 May Impact Earth - What We Know So far [20:22]

YouTube ^

| February 23, 2025

| Dr Ben Miles

Posted on 12/24/2025 6:14:22 PM PST by SunkenCiv

Asteroid 2024 YR4, has sparked concern about its chance of hitting Earth in December 2032. How worried should we be? Scientists Warn Asteroid YR4 May Impact Earth - What We Know So far | 20:22

Dr Ben Miles | 2.17M subscribers | 462,064 views | February 23, 2025

0:00 The Discovery 2024 YR4

0:56 How to Spot an Asteroid

3:07 Ad Read

4:33 Why Are We So Bad at Predicting Asteroid Impacts?

11:42 How Much Damage Could YR4 Do?

13:04 How Could We Stop Asteroid YR4?

16:34 Conclusion

(Excerpt) Read more at youtube.com ...

TOPICS: Astronomy; Science

KEYWORDS: 2024yr4; asteroids; asteroidyr4; astronomy; catastrophism; catsasstrophycoming; fauxiantrolls; multiplenicktrolls; runforyourlives; science; stopgettingourhopeup; wereallgonnadie; yr4

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-40, 41-58 next last

1

posted on

12/24/2025 6:14:22 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

0:00 The Discovery 2024 YR4

0:56 How to Spot an Asteroid

3:07 Ad Read

4:33 Why Are We So Bad at Predicting Asteroid Impacts?

11:42 How Much Damage Could YR4 Do?

13:04 How Could We Stop Asteroid YR4?

16:34 Conclusion

Everyone is kind of worried about this asteroid 2024 YR4. It is a 90 m wide city killer that has caused astronomers around the world to trigger global planetary defense procedures for the first time in history. In fact, in the last few weeks alone, we've gone from no chance it'll hit us to a 1% chance, to a 2% chance, to a now kind of awkwardly specific one in 42% chance. Douglas Adams, is that you? Some estimates say it could unleash a devastating 8 megatons of energy upon impact. That's 500 times that of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, Japan. But why is there so much uncertainty and confusion about where this asteroid is actually heading and whether it will actually hit us? I wanted to find out what we know about YR4 and how worried we need to be that one city is about to become the unluckiest place in the world. I also want to ask the important question: is it finally time to start training a bunch of oil rig drillers how to be astronauts? Let's find out.How to Spot an Asteroid

Our first attempt at spotting asteroids came in 1801 when Giuseppe Piazzi, an Italian astronomer, was charting the positions of stars across several days. He noticed that one happened to be moving. At first, he thought he had spotted a comet, but its slow and steady motion suggested it was something else. After he tracked the object for about 6 weeks, from January 1st to February 11th, 1801, he boldly announced to the world that he had discovered a new planet. He was wrong. Piazzi had actually spotted the very first detected asteroid, Ceres, which, due to a combination of a brief head cold and poor astronomical alignment, then promptly escaped his gaze and sailed out into the darkness of space.

A similar story presents itself with YR4. On December 27th, 2024, as leftover holiday cookies went stale and New Year's resolutions already showed signs of abandonment, Atlas, the Asteroid Terrestrial Impact Last Alert System, a collection of four telescopes across the world—two in Hawaii, one in South Africa, and a final one at El Sauce Observatory in Chile—were all hard at work scanning the night sky. That was until an automated warning signal rang out: an object had been spotted with a chance of impacting Earth within hours. What became known as 2024 YR4 rose to the top of the European Space Agency's asteroid risk list, finally knocking Disturbance off of the top spot of global rock charts. This is what our telescopes saw: early observations suggested it might just be a small 10 to 30 m in diameter asteroid, roughly the size of a bus or small house. NASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies and ESA's Near Earth Object Coordination Center collected more data to refine its orbit, and calculations suggested it would pass extremely close to the Earth but remain outside of our atmosphere. On December 31st, estimates placed YR4 now at just 20 m across, traveling at 15 km a second or 33,500 mph, and it was expected to pass Earth this time within 880,000 km or 50,000 mi, about 1/5 the distance to the Moon. On this first approach, it missed us, but teams around the world were already asking themselves what would happen during its next orbits.Why Are We So Bad at Predicting Asteroid Impacts?

Just like Piazzi, we will only be able to collect limited data on this asteroid's trajectory. As of April 2025, it will slip from our vision, so we have between now and then to collect as much information as possible to understand what it is that we then do with this information. We turn back to Piazzi and his lost Ceres. Ceres may have stayed lost forever with so little measurement time possible to calculate its future pathway. That is, if it wasn't for a brilliant mathematician who developed a new kind of math for determining orbital pathways based on limited observation time. Later that same year, after Piazzi's initial discovery, Carl Friedrich Gauss, a 24-year-old German mathematician, developed the method of least squares, a mathematical technique used to find the best fitting curve or line to a set of data points by minimizing the sum of the squared differences between the observed and predicted values. An incredibly powerful technique and ultimately one of the many banes of high school math classes. Using his least squares method, Gauss predicted where Ceres would reemerge in the night sky, and later that year, in December 1801, astronomer Franz Xaver von Zach, using Gauss's calculations, successfully relocated Ceres as the 473 km wide behemoth reappeared from behind the sun. Now, 225 years later, we are still basically using Gauss's method of least squares to help plot the path of YR4 today. But that makes it sound simpler than it really is.

One of the first problems we encounter when looking for or tracking asteroids like YR4 is albedo. Now, this isn't asteroids getting frisky in space; albedo is a measurement of the reflectivity of a surface, and an albedo of one is equivalent to 100% of the light being reflected. Fresh snow has a reflectivity score of around 90% and is responsible for those embarrassing ski mask sunburns. At the opposite end of the scale, coal has an albedo rating of around 10 to 15%. The Moon has an albedo rating of 7%, which I always find amazing—that the bright, shiny Moon is actually less reflective than a lump of coal. In space, YR4, by some estimates, has an albedo as low as 5%, and that's worrying. Spotting it against the pitch-black night sky, despite being nearly a football field in size, is basically impossible. But albedo's influence doesn't just limit our detection capability; the reflectivity, or lack thereof, of YR4 is what's causing variations in size predictions. Currently, it's believed to be between either 40 or 100 m wide, and that's not necessarily a range; it's more like one or the other. An asteroid with a darker-than-coal-like surface reflects a similar amount of light to a smaller rock with a shinier, chalk-like surface. We think YR4 is this darker material, indicating that it may be at the 90 to 100 m range, entering the range of city-killing asteroids. But there is a chance that it's the brighter and smaller Tunguska-like object, which ranges in size up to 50 m.

NASA is hoping to measure YR4's true size in the near future, as for about 4 hours in March 2025, the James Webb Space Telescope will use its mid-infrared instrument to determine the asteroid's physical properties, including temperature, mass, and chemical composition, which should help us understand its albedo. However, with all of those difficulties in mind, just a few days ago, estimates of YR4's likelihood of impacting Earth went up from 1% to 2% to now 2.3% or one in 42 chance, meaning that all of the criteria necessary to activate the two endorsed asteroid reaction groups—the International Asteroid Warning Network and the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group, or as I like to refer to them, the Asteroid Avengers—have now been called into action. Odds of one in 42 might not sound too bad upon first hearing, but the question is: would you board a plane with a one in 42 chance of crashing? Probably not. This means that YR4 currently ranks at a three on the Torino scale, which is a scale that estimates the likelihood of impact and the potential for devastation, from zero (no chance at all of impact) to 10 (high likelihood of impact and global consequences for that impact). YR4 is the second highest rating ever of any asteroid we've ever detected; only Apophis, the potential planet killer that made headlines in 2004, scored higher. But why are these estimates for impact still changing so much? There are a few other factors at play.

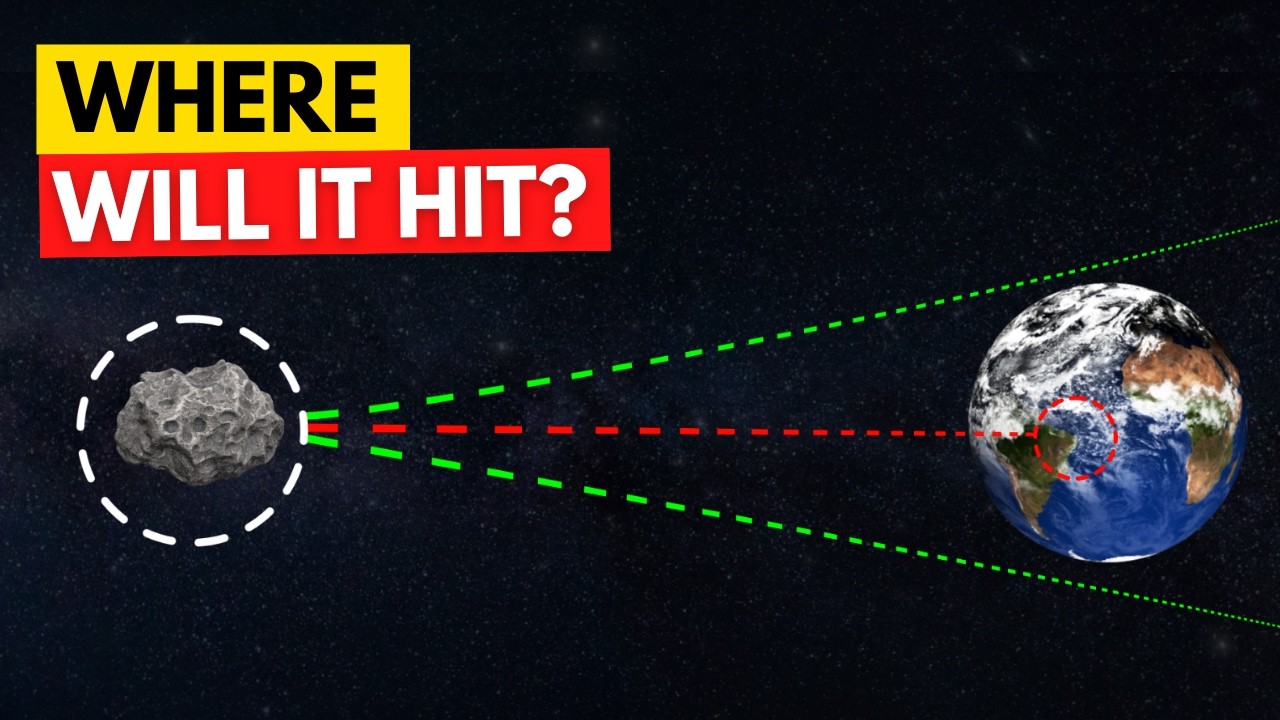

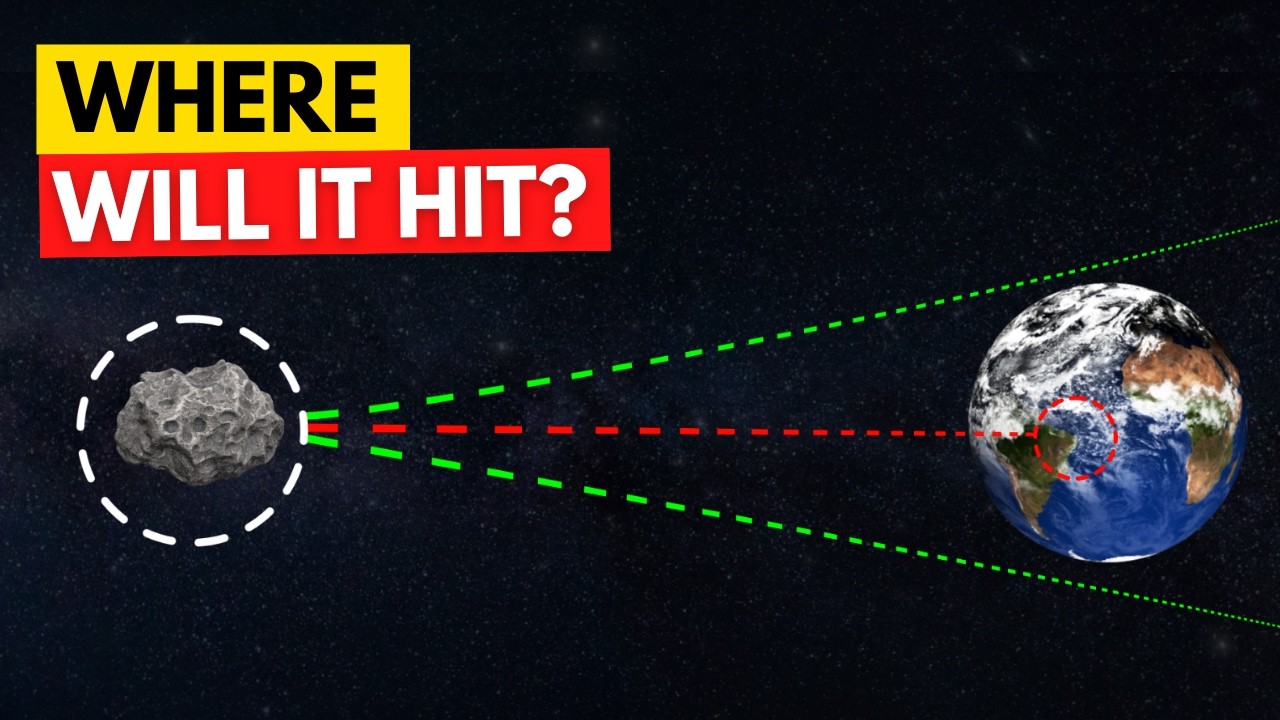

Number one: not only, like Piazzi, do we have limited observation data to work with so far, but if we zoom in to YR4's full orbital pathway, the path begins to look increasingly like a straight line traveling away from Earth. At this point in its trajectory, any errors in our measurements or variations from YR4's movements that we don't accurately detect can put it on wildly different predicted pathways. This is broadly all under the manner of the chaos effect. Even with precise telescopes, our measurements of an asteroid's position and velocity have tiny uncertainties. Over time, these uncertainties compound due to gravitational interactions and mismeasurements and errors, making long-term predictions really difficult to make reliable. What we also see is that YR4's pathway isn't just as simple as an orbit around the Earth. The orbits of asteroids are affected by the gravitational pull of planets, moons, and even other asteroids. Close passes near large planets, especially ones like Jupiter, can significantly alter an asteroid's trajectory in unpredictable ways. There's also maybe a less thought-of phenomenon called the Yarkovsky effect, where the heating of one side of the asteroid caused by the sun can cause off-gassing of frozen material or can cause a steady photonic pressure on the asteroid, slowly changing the asteroid's orbit. This effect depends on the size, shape, material, and a return visit from the albedo of the asteroid, as it will determine how much pressure the sun exerts. There are obviously a few other factors, but the bottom line of this message is that this calculation is kind of hard, and it's okay to be a little off for other asteroids that don't pose much threat to us. But when they look like they will make an impact, every tiny perturbation needs to be taken into account. As time passes, each measurement will hopefully increase our accuracy of the plotting, either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of impact. That is until 2028, when it will make its next close approach to Earth on around the 17th of December, and it will pass as close as 500,000 km from us, about 1.3 times the distance of us to the Moon. The 2028 encounter will provide astronomers with the opportunity to perform additional observations and extend the observational arc by four years, hopefully improving calculations in preparation for our date with destiny in 2032. In the meantime, though, we can run simulations using an orbit simulator to generate 5,000 clones of YR4 under various effects, albedos, and other characteristics. Researchers have modeled future pathways and found that about 70% of them collide with Earth. This collision corridor we can see here creates a horizontal line stretching from the top of South America across the Atlantic Ocean before traversing the Indian Ocean and ending in India. Obviously, it will only hit in one of these locations, and yes, it's important to remember that 70% of the planet is water and only 3% of the planet are cities.How Much Damage Could YR4 Do?

But exactly how bad, in the worst-case scenario, could this be? If we take a city in Colombia as the impact area and assume that YR4 survives entry through our atmosphere, we can estimate, with the data from a similar megaton blast using a nuclear weapon, how devastating the effects might actually be. Here, we'll ignore the radiation radius, which doesn't apply, but we see a 3 km radius for a maximum size of fireball, which would effectively vaporize everything within that fireball. We also see a gigantic 26 km radius of thermal radiation causing third-degree burns for those unfortunate enough not to evacuate. Here, for a medium-sized city, we estimate north of 2 million fatalities, but this number could be much worse in a heavily populated area such as Mumbai; casualties could be north of 6 million. And this is all from an object that is only just slightly bigger than Big Ben. Now, beyond that dive into fear-mongering, I don't want this to be seen as pure fear-mongering. These are worst-case scenarios where the probability drops into fractions of absence. I just wanted to find some clarity on why astronomers around the world have triggered global planetary defense procedures for the very first time. Maybe this is something we shouldn't simply forget about and hope for the best. That may at least allow us to try and figure out which movie universe we're in: either Deep Impact or Don't Look Up. But the question is, if we do choose to act, what could we actually do about it?

[Music]How Could We Stop Asteroid YR4?

Hollywood has made us think that detonating a nuclear device near an asteroid is pretty much the go-to method for planetary defense. But beyond the obvious geopolitical issues of launching nuclear weapons into space, how effective would this actually be? Unlike detonations on Earth, where the surrounding air transmits a shock wave, a nuclear explosion in space behaves differently. With no atmosphere to create the traditional blast wave, the primary effect comes from intense radiation and high-energy particles. If this explosion occurs close enough to the asteroid, these energetic emissions could transfer momentum and heat to the asteroid. But ultimately, this would be far less efficient than explosive forces that we are familiar with in atmospheric detonations.

If, however, the bomb is placed directly on or in the asteroid's surface, the key factor driving its deflection would be thermal radiation, neutron blast, and x-ray heating. These would rapidly vaporize surface material, altering the asteroid's trajectory. Through Newton's third law, this approach, often termed nuclear ablation, relies on the asteroid shedding material explosively to change course. But there is a similar method that doesn't use quite as many atomic weapons. Laser ablation involves heating and vaporizing an asteroid's surface using a very high-powered laser. The expelled material would create a jet-like effect, gradually shifting the object off its path, similar to the nuclear detonation. However, at present, this kind of high-powered laser is purely theoretical.

What is important to understand about both nuclear and laser ablation is that they're not about pushing the asteroid; they work by forcefully ejecting material at high speeds in the opposite direction you want the asteroid to go. That's important to understand because, depending on the asteroid's composition, this could result in just multiple larger fragments breaking off, which might still pose a risk to Earth. Or there is a chance that over time, gravitational forces could cause the debris to slowly reaccumulate. Many asteroids, it turns out, aren't even solid rock but are instead loosely bound rubble piles held together more by gravity than structural integrity. This makes them very different from metallic core remnants like 16 Psyche, which are incredibly dense and tough.

This brings us potentially to a third option that may be more effective and straightforward as a method for asteroid deflection. The kinetic impactor technique is essentially crashing a spacecraft into the asteroid at high speed to change its velocity. But again, how effective is this method in the case that the asteroid isn't actually solid rock? Well, we actually have data that tells us NASA's DART mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, launched on November 2001, set out to answer exactly this question. It targeted Dimorphos, a moonlet orbiting a larger asteroid, Didymos, and aimed to see whether a high-speed impact could significantly alter its trajectory. Before the collision, Dimorphos took 11 hours and 55 minutes to complete one orbit around Didymos. On September 26th, 2022, the DART mission struck at 6.6 km/second or 14,764 m per hour. The post-impact measurements confirmed that the moonlet's orbit had shortened by 32 minutes, a clear demonstration that a kinetic impactor can effectively shift the motion of a rubble pile asteroid.

Each of these proposed solutions suffers from two significant problems: they require time, and they require cooperation.Conclusion

The DART mission started in 2015 before successfully smashing into Dimorphos in 2022, a 7-year time frame that required two of the world's largest space agencies to work together to plan and carry out the mission. If we start today, we might just make it. But who is going to foot the bill? A mission of this scale would require a huge chunk of already stretched budgets. In today's political climate, would NASA or ESA get the sign-off to spend billions on a mission that has a 97.7% chance of not being needed? Or are we in a more terrifying universe, and are we waiting for Elon to step into the fray? Or does this make the film "Don't Look Up" feel more like a prophecy than a satire? People are going to ask why we didn't act earlier, so you're going to have to take the lead on this one. There is some question to ask as to whether nations or corporations would even get involved when they are outside of the risk impact corridor. It could become an international game of "not until 2028," and we're faced with a more accurate reality. Do we make a decision by which point it might be too late? Currently, we are heading down the wait-and-see path, with most agencies rightfully concerned and busy collecting data.

In the meantime, there is, however, one notable exception. A few days ago, China just gave us a little glimpse of hope via a recruitment posting. China's State Administration of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense is now recruiting for a planetary defense team with the aim of diverting similar catastrophes. In a fortunate coincidence, earlier this year, China also announced conceptual plans for kinetic impact missions aimed at targeting and colliding with an asteroid in 2030. Maybe an update to the target of which asteroid they were aiming to impact is all that is needed to save us in 2032. Regardless of China's plans, we can continue to make measurements until April, which is when YR4 disappears and won't return until 2028. I'll be back, but at this moment in history, the way we are responding, or not responding, to the threat says a lot about where we are as a species. We're in what I think of as the age of folly. We've survived successfully the age of whimsy, where all these fun things like famine, pandemic, and natural disasters lead to mass death. You can't really do that much about it other than throw your hands in the air, lament, and write poetry. In the age of folly, we do actually have quite a lot of the tools that may prevent these existential threats, but we also quite like short-term thinking, greed, and gently persistent incompetence, which means we're just as likely to turn these tools on ourselves as use them for our protection. Maybe one day, looking ahead to the future, we get to the age of mastery, a hypothetical place where we both understand the tools and ourselves and are capable of repelling basically any disaster that nature or the cosmos throws our way, except maybe the heat death of the universe. My view, though, is that most civilizations probably don't make it to mastery. The question is, will we, or are we destined to become just another species that almost had the ability to control its destiny but couldn't quite get it together? Either way, at least we'll be collecting data for more than just an asteroid trajectory when YR4 returns in 2028.

If you like this video, hit the subscribe button. We've got some really interesting things coming up soon. If you work on a technical team and solve these sorts of problems out there in the world, I would also be interested in talking to you. I run a venture capital fund called Empirical Ventures, where I back PhD scientists and engineers to help solve some of the biggest problems in the world. I'll leave a link down in the description where you can find out more.

[ad text redacted] Thanks for watching, and try not to lose sleep over any rogue asteroids.

Goodbye.

[Music]

2

posted on

12/24/2025 6:15:28 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

https://search.brave.com/search?q=Asteroid+2024+YR4&summary=1

Asteroid 2024 YR4 is a near-Earth object discovered on 27 December 2024 by the ATLAS–CHL (W68) telescope in Río Hurtado, Chile, with precovery images dating back to 25 December 2024.

It is classified as an Apollo-type asteroid with an elliptical orbit that crosses Earth’s path, having a semi-major axis of 2.5158 AU and an orbital period of approximately 3.991 years.

The asteroid made a close approach to Earth on 25 December 2024, passing at a distance of 828,800 km (515,000 miles; 2.156 lunar distances), two days before its discovery, and then passed 488,300 km (303,400 miles; 1.270 LD) from the Moon.

Initial observations raised concerns about a potential Earth impact in 2032, with probabilities peaking at around 3%, but further tracking confirmed that there is no significant risk to Earth.

Instead, current models indicate a 4% chance that 2024 YR4 will impact the Moon on 22 December 2032.

The asteroid is estimated to be about 60±7 meters in diameter, likely composed of stony S-type, L-type, or K-type material, and rotates approximately every 19.5 minutes.

The James Webb Space Telescope observed it on 26 March 2025, refining its size and spectral characteristics, and future observations, particularly around its 2028 close approach to Earth, are expected to improve predictions of its trajectory.

AI-generated answer. Please verify critical facts.

3

posted on

12/24/2025 6:16:02 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

The rest of the 2024 YR4 keyword, sorted:

4

posted on

12/24/2025 6:16:26 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

To: 75thOVI; Abathar; agrace; aimhigh; Alice in Wonderland; AnalogReigns; AndrewC; aragorn; ...

5

posted on

12/24/2025 6:17:14 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

To: SunkenCiv

6

posted on

12/24/2025 6:18:22 PM PST

by

BipolarBob

(These violent delights have violent ends.)

7

posted on

12/24/2025 6:19:22 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

To: BipolarBob

Nah.

Vance's Fault by that time.

8

posted on

12/24/2025 6:19:23 PM PST

by

Harmless Teddy Bear

(It's like somebody just put the Constitution up on a wall …. and shot the First Amendment -Mike Rowe)

To: SunkenCiv

I, for one, plan on being out of town that day.

9

posted on

12/24/2025 6:19:45 PM PST

by

fidelis

(👈 Under no obligation to respond to rude, ignorant, abusive, bellicose, and obnoxious posts.)

To: fidelis; BipolarBob

10

posted on

12/24/2025 6:21:16 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good night!)

To: SunkenCiv

To: SunkenCiv

12

posted on

12/24/2025 6:22:47 PM PST

by

Kleon

To: SunkenCiv

New bumper sticker

Giant Asteroid 2032

13

posted on

12/24/2025 6:26:23 PM PST

by

Secret Agent Man

(Gone Galt; not averse to Going Bronson.)

To: SunkenCiv

It’s SMOD coming to save us!

14

posted on

12/24/2025 6:27:16 PM PST

by

Jonty30

(Escasooners are faster than escalators,)

To: Harmless Teddy Bear

Although in Ivanka’s second term, the Dems like white haired AOC will blame her and her dad.

Scenario: Missiles ready to head for the asteroid with the ability to break it into harmless piece.

Federal judge rules to stop it with an injunction. SCOTUS agrees that the proper environmental impact statements have not been approved. So the other type of “impact” will proceed. Millions will die so the Court’s power and dignity will remain intact.

As Judge Smails said to the young caddy in Caddyshack: “I’ve had to send people younger than you to the electric chair. I didn’t want to. But I felt I owed it to them, somehow.”

15

posted on

12/24/2025 6:27:37 PM PST

by

frank ballenger

(There's a battle outside and it's raging. It'll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls. )

To: Roman_War_Criminal; SaveFerris

Hmmm, Revelation anyone?

That’s SEVEN years from now. Imagine that.......

16

posted on

12/24/2025 6:32:43 PM PST

by

metmom

(He who testifies to these things says, “Surely I am coming soon." Amen. Come, Lord Jesus….)

To: BipolarBob

8 megatons much of which will be high in the air as it disintegrates. Castle Bravo nuclear test in the South Pacific was 15 megatons, but by error. The explosion was much greater that predicted. Result was the Island gone, more radiation than predicted and some evacuations of Islands around it for years and some deaths due to radioation. It was a complete F—k Up due to bad calculations by the physicists. It also made a new definition of “quick fried” fish, oysters, sharks, crabs, and an Island.

Unless this astroid comes down over a heavilly populated area it will be of little consequence. If it comes down over the ocean it will be of no consequence. 71 percent of the earth is ocean.

17

posted on

12/24/2025 6:36:53 PM PST

by

cpdiii

(cane cutter, deckhand, oilfield roughneck, drilling fluid tech, geologist, pilot, pharmacist, MAGA)

To: metmom

18

posted on

12/24/2025 6:37:05 PM PST

by

No name given

( Anonymous is who you’ll know me as )

To: Harmless Teddy Bear

Or DeSantis’s fault or Rubio’s fault.

19

posted on

12/24/2025 6:38:09 PM PST

by

No name given

( Anonymous is who you’ll know me as )

To: SunkenCiv

It won’t matter because Yellowstone will have already erupted by then and maybe some of the other Super volcanoes.

An asteroid strike will be a piker by comparison.

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-40, 41-58 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson

0:00 The Discovery 2024 YR4

0:00 The Discovery 2024 YR4