Posted on 02/25/2022 5:47:24 AM PST by Red Badger

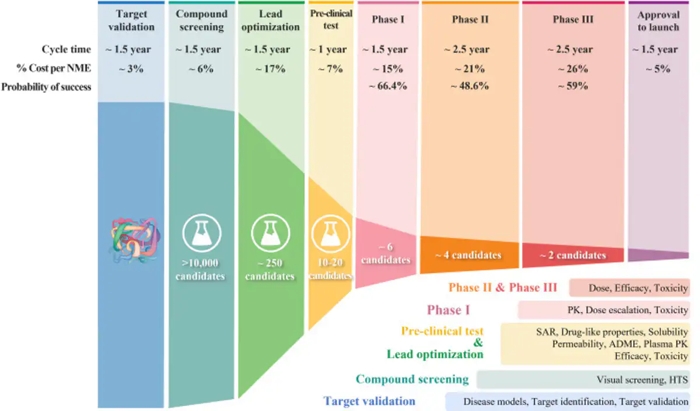

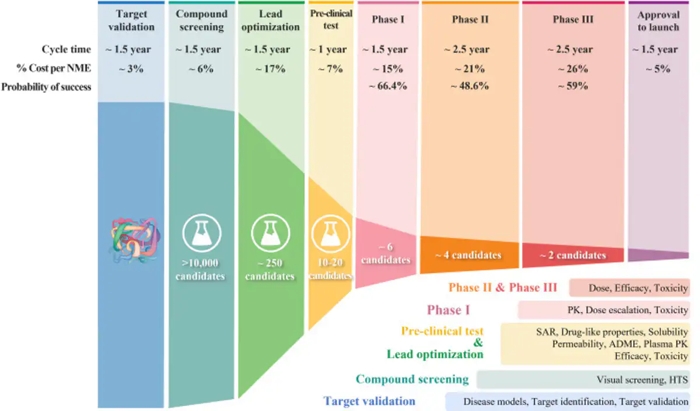

It takes 10 to 15 years and around US$1 billion to develop one successful drug. Despite these significant investments in time and money, 90 percent of drug candidates in clinical trials fail.

Whether because they don't adequately treat the condition they're meant to target or the side effects are too strong, many drug candidates never advance to the approval stage.

As a pharmaceutical scientist working in drug development, I have been frustrated by this high failure rate. Over the past 20 years, my lab has been investigating ways to improve this process.

We believe that starting from the very early stages of development and changing how researchers select potential drug candidates could lead to better success rates and ultimately better drugs.

How does drug development work? Over the past few decades, drug development has followed what's called a classical process. Researchers start by finding a molecular target that causes disease – for instance, an overproduced protein that, if blocked, could help stop cancer cells from growing.

They then screen a library of chemical compounds to find potential drug candidates that act on that target. Once they pinpoint a promising compound, researchers optimize it in the lab.

VIDEO AT LINK........................

Drug optimization primarily focuses on two aspects of a drug candidate.

First, it has to be able to strongly block its molecular target without affecting irrelevant ones. To optimize for potency and specificity, researchers focus on its structure-activity relationship, or how the compound's chemical structure determines its activity in the body.

Second, it has to be "druglike," meaning able to be absorbed and transported through the blood to act on its intended target in affected organs.

Once a drug candidate meets the researcher's optimization benchmarks, it goes on to efficacy and safety testing, first in animals, then in clinical trials with people.

Why does 90 percent of clinical drug development fail? Only one out of 10 drug candidates successfully passes clinical trial testing and regulatory approval. A 2016 analysis identified four possible reasons for this low success rate.

The researchers found between 40 percent and 50 percent of failures were due to a lack of clinical efficacy, meaning the drug wasn't able to produce its intended effect in people.

Around 30 percent were due to unmanageable toxicity or side effects, and 10-15 percent were due to poor pharmacokinetic properties, or how well a drug is absorbed by and excreted from the body. Lastly, 10 percent of failures were attributed to lack of commercial interest and poor strategic planning.

This high failure rate raises the question of whether there are other aspects of drug development that are being overlooked. On the one hand, it is challenging to truly confirm whether a chosen molecular target is the best marker to screen drugs against.

On the other hand, it's possible that the current drug optimization process hasn't been leading to the best candidates to select for further testing.

(Duxin Sun and Hongxiang Hu)

Above: With each successive step of the drug development process, the probability of success gets increasingly smaller.

**********************************************************************************************

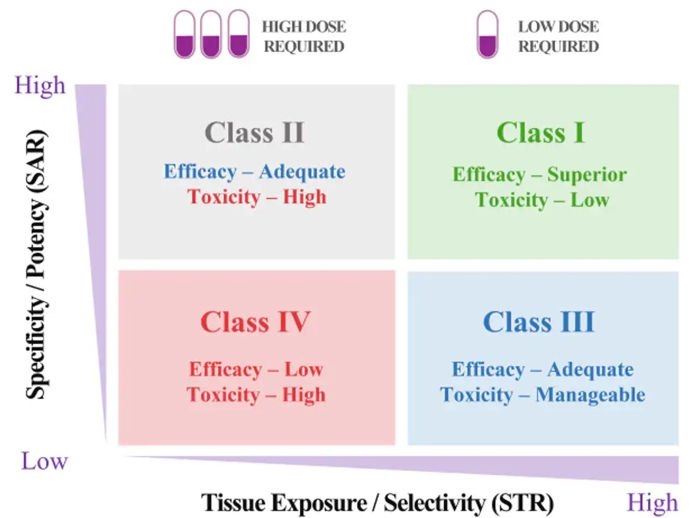

Drug candidates that reach clinical trials need to achieve a delicate balance of giving just enough drug so it has the intended effect on the body without causing harm. Optimizing a drug's ability to pinpoint and act strongly on its intended target is clearly important in how well it's able to strike that balance.

But my research team and I believe that this aspect of drug performance has been overemphasized. Optimizing a drug's ability to reach diseased body parts in adequate levels while avoiding healthy body parts – its tissue exposure and selectivity – is just as important.

For instance, scientists may spend many years trying to optimize the potency and specificity of drug candidates so that they affect their targets at very low concentrations.

But this might be at the expense of ensuring that enough drug is reaching the right body parts and not causing harm to healthy tissue. My research team and I believe that this unbalanced drug optimization process may skew drug candidate selection and affect how it ultimately performs in clinical trials.

Improving the drug development process:

Over the past few decades, scientists have developed and implemented many successful tools and improvement strategies for each step of the drug development process.

These include high-throughput screening that uses robots to automate millions of tests in the lab, speeding up the process of identifying potential candidates; artificial intelligence-based drug design; new approaches to predict and test for toxicity; and more precise patient selection in clinical trials.

Despite these strategies, however, the success rate still hasn't changed by much.

My team and I believe that exploring new strategies focusing on the earliest stages of drug development when researchers are selecting potential compounds may help increase success.

This could be done with new technology, like the gene editing tool CRISPR, that can more rigorously confirm the correct molecular target that causes disease and whether a drug is actually targeting it.

And it could also be done through a new STAR system my research team and I devised to help researchers better strategize how to balance the many factors that make an optimal drug.

Our STAR system gives the overlooked tissue exposure and selectivity aspect of a drug equal importance to its potency and specificity. This means that a drug's ability to reach diseased body parts at adequate levels will be optimized just as much as how precisely it's able to affect its target.

To do this, the system groups drugs into four classes based on these two aspects, along with recommended dosing. Different classes would require different optimization strategies before a drug goes on to further testing.

(Duxin Sun and Hongxiang Hu)

Above: The STAR system provides a systematic way to approach drug candidate selection, taking into account different factors that play a role in how clinically successful a drug may be.

**********************************************************************************************

A Class I drug candidate, for instance, would have high potency/specificity as well as high tissue exposure/selectivity. This means it would need only a low dose to maximize its efficacy and safety and would be the most desirable candidate to move forward.

A Class IV drug candidate, on the other hand, would have low potency/specificity as well as low tissue exposure/selectivity. This means it likely has inadequate efficacy and high toxicity, so further testing should be terminated.

Class II drug candidates have high specificity/potency and low tissue exposure/selectivity, which would require a high dose to achieve adequate efficacy but may have unmanageable toxicity. These candidates would require more cautious evaluation before moving forward.

Finally, Class III drug candidates have relatively low specificity/potency but high tissue exposure/selectivity, which may require a low to medium dose to achieve adequate efficacy with manageable toxicity. These candidates may have a high clinical success rate but are often overlooked.

Realistic expectations for drug development Having a drug candidate reach the clinical trial stage is a big deal for any pharmaceutical company or academic institution developing new drugs. It's disappointing when the years of effort and resources spent to push a drug candidate to patients so often lead to failure.

Improving the drug optimization and selection process may significantly improve success of a given candidate.

Although the nature of drug development may not make reaching a 90 percent success rate easily achievable, we believe that even moderate improvements can significantly reduce the cost and time it takes to find a cure for many human diseases. Duxin Sun, Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Michigan.

This is a similar issue to cybersecurity in new product development. We’ve been working for years to inject a security mindset into the development process from the beginning, but too often we still see new products, esp. on the web, that are full of holes in order to speed to market. I’m glad to see the problem isn’t unique to IT.

I’m not taking anything made after 2000.

I’m going to turn into a hippie and use plants…

When you get it all secure, let us know, and we’ll un-corrupt the government. ;)

The idea of nasal Covid vaccines comes to mind that would break the infection cycle.

Try as I might for the last 10 years, few developers actually listen. They’re under tight deadlines to get things out into their pipelines, and security is often a stumbling block for them. Sad, really, and a big reason why I’ll likely be employed until I’m on death’s door.

“side effects are too strong”

That has been my observation with so many modern drugs. Unless the med is supposed to cure a critical medical condition or save a life, the problems caused by side effects can outweigh it’s benefits.

Or you could develop a completely new drug and call it a miracle “vaccine” with practically no testing and absolutely no idea what the long term effects will be.

And then pay off or marginalize anyone who points out that your miracle vaccine not only doesn’t work, but many thousands of people will be permanently injured or even killed by it.

After the vax nonsense he needs to stfu.

Drugs are usually patented early in the development process. A long clinical trial cuts a significant portion of the patent life of the drug. But safety and efficacy are top priorities. It would be nice to see the process streamlined.

Good observations, but they’re not factoring in the drug companies’ GREED and DISHONESTY. Once those two items are added to the equation, it starts to make sense. I mean, not MAKE SENSE, but it’s more understandable.

The last time I saw a doctor was in 2003 or 2004. I don’t take any prescription medications. I’ve worked in too many clinics and hospitals and stopped trusting the system a long time ago. Do you think I’m nuts? I’ve outlasted a lot of people who heaped scorn on me for not running to the doctor for every little thing. I don’t see people having a good time out there on all these medications and procedures that doctors try to talk you into.

Before my mom started yelling at me about vaccinations she told me with a little laugh, “I had a hip replacement and now I can’t walk anymore!”

I do take vitamins and herbs and some over-the-counter things like Benadryl, aspirin, fiber supplement - really simple stuff. I’ve been taking garlic every day for many years.

I got Mr K (not the one on this forum) to start taking garlic: When I first met him he had a bald place on the top of his head about the size of an audio CD. His hair started growing back and there’s no longer a bald spot - some of the hair even grew back its original color. (He looks like Dr Von Helsing! or Beethoven, sort of.)

And you know I’m NOT the picture of excellent health but on the other hand I’m not laying out hundreds of dollars a month for the ten or twenty pharmaceuticals doctors would have me taking at my age - I mean, they give this stuff to EVERYBODY and you’re supposed to be happy and grateful to have to take like 30 pills a day. And I would be vaccinated and all that happy h0rsesh1t. I think it’s at least probable that one of the reasons I’m still flapping today is the LACK of medical intervention.

The pandemic illustrates this point quite admirably: The most effective treatments and prophylaxis against the SARS-CoV2 are SIMPLE medicines that have been around for A LONG TIME.

Drug developers are still spending a lot of time and money on the holy grail of pharmacology - female viagra.

Hmmm. I was aware of the rough timeline and costs associated with bringing new drug therapies to market. I did not realize the failure rate was that high.

Given this track record, when it comes to the covid-19 vaccines something is very definitely amiss.

I have no doubt truckloads of cash were spent.

10 to 15 years? These were developed in days (Moderna is particularly proud of how rapidly they developed theirs), tested over the span of mere weeks and approved after just a few years.

All this while 2 of the 3 are utilizing brand new, never before put to widespread use mRNA technology. Obviously corners were cut, procedures ignored or modified. Note, those procedures were put in place to help ensure the safety of the products brought to market. They were learned "the hard way" and they have not been followed in this case.

90% failure rate? Well, the FDA seems to be running either an out-of-character 25% failure rate, or even an astounding 0% failure rate with covid vaccines. I know of 4 that were submitted for approval, 3 are approved, and the 4th is not yet completely out of the running.

Amazing that vaccines developed in such a rush with new technologies could experience such previously unheard of success rates. It's almost like they aren't allowed to fail...

Ok, yes, lightning does strike once in a while. But what is more likely, that vaccines rushed through development, using new technologies, just happen to have been nearly universally successful? Or is it more likely that most, probably even all of these should have failed clinical trials. That they did not can be attributed to rule breaking, corner-cutting, and a flat out dis-interest in following procedures or considering negative data.

If the truth ever comes out people are going to prison over this. Though I doubt we'll ever know the complete story behind this BS. Maybe if enough people start experiencing serious long term side effects there will be enough interest by people with integrity to dig into this fiasco and learn the truth.

I hate saying things like that about medicines that I know a lot of people can’t live without. But on the other hand, me talking trash about the medical drugs industry isn’t why nobody trusts them anymore - they’re the ones who did that. They did it to themselves.

Almost every medication I remember internal medicine/family practice doctors I’ve worked for giving to people over age 50 has been found to do something bad to you over time - and they give them to EVERYBODY and you’re supposed to take them EVERY DAY. Like Metformin. They were giving that out like candy - very expensive candy - to all kinds of people. And it’s pretty bad, I guess. Anticholinergic medications are another that comes to mind: They are shown over time to cause cognitive impairment. (So you’ll have a heart/bladder problem AND dementia, too!)

If it wasn’t so blatantly obvious at this point that we’re being lied to and played - and in some cases conveniently killed off - then I would just be another conspiracy theorist who likely has a grudge at some doctor. (I DO have a grudge against a medical practitioner, in fact - but it’s over a stalking issue that started when I worked in his office a long time ago.) The pharmaceuticals industry cynically thinks that we are all A) stupid and B) lazy - that is, we are all so lazy that we don’t bother to take care of ourselves, thinking that the doctor will have a pill or treatment that will fix us. Just take the pills, and all will be well!

Drug commercials are just another reason I am glad we don’t have TV.

That's always been the challenge of pharmaceutical science and the practice of medicine--weighing the risk/benefits for each disease state. Risking death for a drug that helps patients with ED may be considered extreme; risking death for a patient with pancreatic cancer? That's an entirely different risk calculus.

I support this goal.

That thing exists, it's called Chad. And Chad isn't worried about female Viagra, he gets more than he can handle.

Women (and non Chads) want a female Viagra so they can feel about the guy who brings out the garbage and is dependable the way thy feel about the Chad. DTF.

Female psychology is interesting, if nothing else.

“ On average, about 4,500 drugs and devices are pulled from U.S. shelves each year. The recalled products have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and in many cases, are widely ingested, injected or implanted before being recalled.”

Being approved is only part of the story.

But the FDA is more worried someone may take too much vitamin C and get the runs.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.