Posted on 06/03/2010 7:32:55 PM PDT by SeekAndFind

It was 15 months ago that Science carried a story about the completion of a rough draft of the Neandertal genome. Palaeogeneticist Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig was reported as saying "he can't wait to finish crunching the sequence through their computers". It has been quite a long time coming, as it is more than a decade since Paabo first demonstrated it was possible to analyse Neandertal DNA sequences. Earlier reports suggested that Neandertals were sufficiently distinct from humans for them to be classified as a separate species of Homo. The draft genome has more than 3 billion nucleotides collected from three female Neandertals.

"By comparing this composite Neandertal genome with the complete genomes of five living humans from different parts of the world, the researchers found that both Europeans and Asians share 1% to 4% of their nuclear DNA with Neandertals. But Africans do not. This suggests that early modern humans interbred with Neandertals after moderns left Africa, but before they spread into Asia and Europe. The evidence showing interbreeding is "incontrovertible," says paleoanthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the work. "There's no other way you can explain this"."

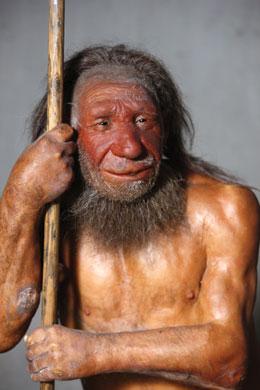

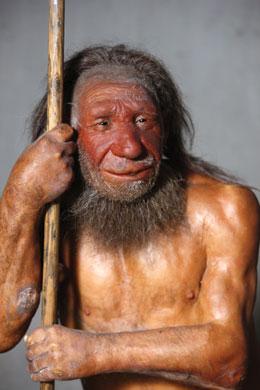

Neanderthals once bred with Homo sapiens. (credit PHOTOLIBRARY, source here)

Genetically, then, Neandertals are not altogether extinct. Paabo is quoted as saying: "They live on in some of us". Therefore, the 'Out-of-Africa' model needs revision, as the migrants interbred to some extent with Neandertals and their genetic signatures spread through the migrant populations. According to Rex Dalton in Nature:

"That revelation is likely to revive the debate about whether or not the two groups are separate species, says anthropologist Fred Smith of Illinois State University in Normal, who has studied Neanderthals in Europe. Smith thinks that they are a subspecies of H. sapiens. Now that the genomes can be compared, it will be possible to investigate the genetic roots of some shared features."

This theme is picked up in the pages of New Scientist, and especially noteworthy is the editorial: "Welcome to the human family, Neanderthals". It calls for Neanderthals to be given a warm reception as truly human relatives.

"Svante Paabo, the pioneer of palaeogenetics, equivocated when a reporter asked whether his genome study suggested Neanderthals are the same species as us: "I would more see them as a form of humans that were a bit more different than people are from each other today, but not that much."

Why so shy? Putting aside the vexing question of what defines a species - which flummoxed even Linnaeus and Darwin - it is hard to see why Neanderthals should now be considered as anything other than Homo sapiens. We know that Neanderthals bred with our ancestors and produced fertile offspring, which is one hallmark of a species. And there is plenty more evidence to support giving them the status of Homo sapiens neanderthalis. Neanderthals shared a common ancestor with modern humans around 500,000 years ago. Its descendants went their separate ways as the Neanderthals adapted to colder climes, but then, at least 50,000 years ago, they resumed relations in the eastern Mediterranean, where the two populations met again. This pattern wouldn't necessarily merit separate species status for most animals, so why for us and Neanderthals?"

There is undoubtedly some journalistic enthusiasm here, because the claimed "hallmark of a species" is not valid: hybridisation is not that unusual between species and sometimes it occurs between genera (within the same family). This in itself is not a decisive argument. However, when we combine genetics, morphology and behaviour, the picture looks much clearer.

"There is, of course, more to the concept of being human than ecology and genetics: we are human because we think, talk, love and believe. It is impossible to know the mental life of a Neanderthal, but there is reason to think that it was not so different from our own. The Neanderthal genome differed little from ours, encoding fewer than 100 changes that would affect the shape of proteins. True, some of these differences occur in genes linked to brain function, but similar variation is found among humans today. Moreover, Neanderthals share with us a version of a gene linked to the evolution of speech, and recent archaeological evidence suggests that their minds were capable of the symbolic representations that underlie language and art. If that's not human, then what is?"

This brings us to why Neandertals have been so misinterpreted over the years. Why has it taken us so long to reject the picture of a brutish, grunting caveman devoid of aesthetics and reason? The Editorial starts with these words: "WE HUMANS like to see ourselves as special, at the very pinnacle of all life. That makes us keen to keep a safe distance between ourselves and related species that threaten our sense of uniqueness. Unfortunately, the evidence can sometimes make that difficult." Is this interpretation valid? Do we like to keep a safe distance between ourselves and anything that threatens our uniqueness? Perhaps we should reflect on on the history of scientific racialism, that portrayed races as occupying different rungs of the evolutionary ladder - was this also to keep a safe distance from races that threatened our uniqueness? Furthermore, is it true that we, the population at large, like to keep this safe distance? Why is it that any reports of animals showing apparent cognitive and creative skills are deemed newsworthy, whereas other studies showing a big divide between humans and animals languish in obscurity? I leave these questions for further thought and reflection.

One thing I have noticed over the years is that people with a design perspective have been far more receptive to the idea that Neandertals were part of the human family. They have been impressed by morphological considerations, but the cultural artifacts of Neandertals have made a big impression. In the early days, these were relatively meager, but more recent years have seen a flowering of reports of Neandertal culture. In this blog, these issues have been explored on several occasions: Burying the view that Neanderthals were half-wits, Darwinist thinking on the origin of religion, The cognitive skills of Stone Age Man, Images of evolution as secular icons, Walks like a man, talks like a man - is it a man?, and Rethinking Neanderthals. There is a pattern here, and it is evident even in the original reception given to Neandertal finds. The Darwinian scientists were looking for intermediates and they found one in Neandertal Man. He was portrayed as an ape-man and used to prop up an evolutionary story of ape-to-man evolution. After it was realised that the original finds were bones from someone deformed by disease, the story did not change much. The icon was too important to lose. Darwinism had created a blind spot for palaeoanthropologists and impaired the progress of science. Those able to make design inferences within science have been ahead of the game, but now the genetic data is published, all have to follow. However, would you believe, the same issue of New Scientist that carried the editorial noted above also had an article with the title: "Neanderthals not the only apes humans bred with". Apes? Really! Outdated traditions do not die when it comes to Darwinism - they just get repackaged!

A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome

Richard E. Green [et al] and Svante Paabo

Science, 328, 7 May 2010: 710-722 | DOI: 10.1126/science.1188021

Abstract: Neandertals, the closest evolutionary relatives of present-day humans, lived in large parts of Europe and western Asia before disappearing 30,000 years ago. We present a draft sequence of the Neandertal genome composed of more than 4 billion nucleotides from three individuals. Comparisons of the Neandertal genome to the genomes of five present-day humans from different parts of the world identify a number of genomic regions that may have been affected by positive selection in ancestral modern humans, including genes involved in metabolism and in cognitive and skeletal development. We show that Neandertals shared more genetic variants with present-day humans in Eurasia than with present-day humans in sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting that gene flow from Neandertals into the ancestors of non-Africans occurred before the divergence of Eurasian groups from each other.

See also:

Dalton, R., Ancient DNA set to rewrite human history, Nature, 465, 148-149, (12 May 2010) | doi:10.1038/465148a

Editorial, Welcome to the human family, Neanderthals, (New Scientist, 12 May 2010)

Gibbons, A., Close Encounters of the Prehistoric Kind, Science 328, 7 May 2010: 680-684.

Re Neanderthals more than likely diabetic. This does not make sense, as their diet probably had relatively little carbohydrate in it, being mostly meat based. Thus diabetes would not likely get expressed.

A semantic thing. It’s not like diabetes is a disease ~ it’s a genetic condition. You got it or you don’t. Folks with an all meat diet with little more to eat than lingonberries and moss probably keep their blood sugar quite in balance by producing exactly what they need.

I like your hypothesis. Given an "out of Africa" human population encountering a Neanderthal population, some amount of interbreeding would have occurred. It now seems that hybrids were viable. A hybrid African/Neanderthal might have been better able to survive in temperate-to-cold climates than either pure African or pure Neanderthal, and so the population with the right mix of Neanderthal genes would have spread.

In fact, all vertebrate animals share pretty much the same base of skeletal parts, internal organs, chemistry, etc. Essentially the same genes make the same things, species by species.

We are much more than brothers to the other species that share this world with us.

Now, when you get to epigenetics, or the control features exterior to the main DNA strands, you run into VAST differences.

That's where you will find the stuff that makes us human. It also makes cows cows, and pigs pigs.

We only recently discovered epigenetics and really have little idea how it works.

The Europeans are the ones with virtually all the red-heads though!

Given the diversity of human characteristics (short dark African Pygmy; blond blue-eyed Scandinavian; Japanese; etc) it makes more sense to consider Neanderthals a different race of humans rather than a different species, given evidence of interbreeding.

Agreed, up to a point.

This entire thread is premised on the idea that interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals can be, and has been, demonstrated through genetic markers.

For sake of discussion I accept the premise, even though am not at all certain it has been proved beyond reasonable doubt. No doubt that future research will either confirm and reconfirm it, or possibly just show how today's researchers got it wrong.

In either case, that would not be the first time it's happened. ;-)

Humans love to mate. They mate all the time, by night and by day, through all the phases of the female’s reproductive cycle. Given the opportunity, humans throughout the world will mate with any other human. The barriers between races and cultures, so cruelly evident in other respects, melt away when sex is at stake. Cortés began the systematic annihilation of the Aztec people--but that did not stop him from taking an Aztec princess for his wife. Blacks have been treated with contempt by whites in America since they were first forced into slavery, but some 20 percent of the genes in a typical African American are white. Consider James Cook’s voyages in the Pacific in the eighteenth century.Cook’s men would come to some distant land, and lining the shore were all these very bizarre-looking human beings with spears, long jaws, browridges, archeologist Clive Gamble of Southampton University in England told me. God, how odd it must have seemed to them. But that didn’t stop the Cook crew from making a lot of little Cooklets. Project this universal human behavior back into the Middle Paleolithic. When Neanderthals and modern humans came into contact in the Levant, they would have interbred, no matter how strange they might initially have seemed to each other. If their cohabitation stretched over tens of thousands of years, the fossils should show a convergence through time toward a single morphological pattern, or at least some swapping of traits back and forth.

But the evidence just isn’t there, not if the TL and ESR dates are correct. Instead the Neanderthals stay staunchly themselves. In fact, according to some recent ESR dates, the least Neanderthalish among them is also the oldest. The full Neanderthal pattern is carved deep at the Kebara cave, around 60,000 years ago. The moderns, meanwhile, arrive very early at Qafzeh and Skhul and never lose their modern aspect. Certainly, it is possible that at any moment new fossils will be revealed that conclusively demonstrate the emergence of a Neandermod lineage. From the evidence in hand, however, the most likely conclusion is that Neanderthals and modern humans were not interbreeding in the Levant.

Of course, to interbreed, you first have to meet. Some researchers have contended that the coexistence on the slopes of Mount Carmel for tens of thousands of years is merely an illusion created by the poor archeological record. If moderns and Neanderthals were physically isolated from each other, then there is nothing mysterious about their failure to interbreed. The most obvious form of isolation is geographic. But imagine an isolation in time as well. The climate of the Levant fluctuated throughout the Middle Paleolithic--now warm and dry, now cold and wet. Perhaps modern humans migrated up into the region from Africa during the warm periods, when the climate was better suited to their lighter, taller, warm-adapted physiques. Neanderthals, on the other hand, might have arrived in the Levant only when advancing glaciers cooled their European range more than even their cold-adapted physiques could stand. Then the two did not so much cohabit as time-share the same pocket of landscape between their separate continental ranges.

While the solution is intriguing, there are problems with it. Hominids are remarkably adaptable creatures. Even the ancient Homo erectus- -who lacked the large brain, hafted spear points, and other cultural accoutrements of its descendants--managed to thrive in a range of regions and under diverse climatic conditions. And while hominids adapt quickly, glaciers move very, very slowly, coming and going. Even if one or the other kind of human gained sole possession of the Levant during climatic extremes, what about all those millennia that were neither the hottest nor the coldest? There must have been long stretches of time--perhaps enduring as long as the whole of recorded human history--when the Levant climate was perfectly suited to both Neanderthals and modern humans. What part do these in-between periods play in the time-sharing scenario? It doesn’t make sense that one human population should politely vacate Mount Carmel just before the other moved in.

If these humans were isolated in neither space nor time but were truly contemporaneous, then how on earth did they fail to mate? Only one solution to the mystery is left. Neanderthals and moderns did not interbreed in the Levant because they could not. They were reproductively incompatible, separate species--equally human, perhaps, but biologically distinct. Two separate species, who both just happened to be human at the same time, in the same place.

This was a big fricking mystery until they managed to extract and study Neanderthal DNA, which is generally described as about halfway between ours and that of a chimpanzee. That explained the mystery; we could no more interbreed with Neanderthals than we could with dogs or cats.

Neither Neanderthal or our modern human DNA is anywhere near that of chimps. In fact, it's beginning to look like the critters that broke off from Ardi, who was barely an ape, were far from being chimps even though the chimps descended from them later on.

The Europeans are the ones with virtually all the red-heads though!Reason enough to be smug. ;')

Yeah they do:

Yuppy "scientists" and evolosers KNOW they have a problem with this stuff i.e. that all other hominids were further removed from US THAN the neanderthal and that if we couldn't be descended from the Neanderthal, we could not be descended from any of them; that's the rational for the revisionism which you're seeing in these current articles.

The rounded torso is basically that of an ape; our torsos are elongated.

No, they don't look like apes. In fact, they have an upright stance, a brain case larger than yours, and when fully grown could be 700 to 900 pounds!

No tree climbing for them.

That’s MtDNA stuff. Now we are talking about full genome ~ not just mitochondria.

Where do you get the 700 lbs?? I mean, I’ve never heard that one.

They were LARGE PEOPLE and ate lots and lots of meat.

The 700 pound computation comes from the fact that Neanderthals were about 30% heavier than other contemperaneous humans, but all these guys were about 5' tall ~ whether Neanderthal or something else.

Bringing them all up to MODERN sized folks at 7 ft would give you a 700 pound Neanderthal with no problem at all.

The point is to show that they were far more heavily muscled and lived a rugged life, and had larger bones.

Your basic Neanderthal was built like a sort of a cross between a chimpanzee and an eskimo and might have been slightly stronger than an average human but could not possibly have been as strong as a typical NFL linebacker, much less a down lineman.

Yeah, they could be much stronger than any modern linebacker.

Believe in fairytales if you want to....

They even had the special bone in the throat necessary for speech and definitely they had greater cranial capacity than most modern people.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.