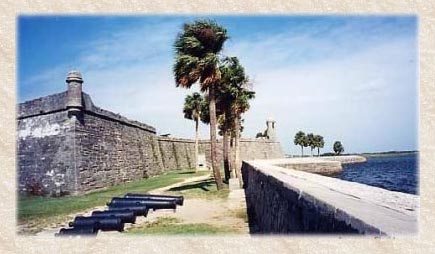

The Castillo de San Marcos, built 1672-1695, served primarily as an outpost of the Spanish Empire, guarding St. Augustine, the first permanent European settlement in the continental United States and also protecting the sea route for treasure ships returning to Spain. It is the oldest major engineered structure existing in America.

To reach the Castillo de San Marcos you must drive through part of the city of Saint Augustine. Saint Augustine is in northeastern Florida near the Atlantic Ocean.

You drive on a small, narrow road with vehicles slowly going both ways. On one side of the road is water. On the other side is the city.

You pass businesses, eating places, stores and hotels. And then you see it, just as the road turns to the left. It looks like a hill of rock rising out of the ground. It seems fierce. And it looks very foreign. There can be no mistake about what it is. It is a very old military base -- the kind that is called a fort. It looks like it should be in some European country, not on the coast of Florida.

Passing through the huge walls of the fort is a little like walking back in time. Today we take you back into the past with a tour of the Fort and it's rich history.....

The First Spanish Period 1565 - 1763 The First Spanish Period 1565 - 1763

Having sighted the land of La Florida in August 28, the feast day of Saint Augustine, Pedro Menendez de Aviles landed on the shore of what is today Matanzas Bay on September 8, 1565, and thus began the founding of the Presidio of San Agustín. The town was to serve very important functions for the Spanish Empire. It defended the primary trade route to Europe and the Bahama Channel (today called the Gulf Stream). It also served as Florida's territorial capital, defending against encroachment into the northern reaches of the Spanish Empire.

The Castillo was not the first fort built by the Spanish but was in fact the tenth, with the previous nine forts being built of wood. Following a pirate attack on St. Augustine in 1668, the Queen Regent Mariana made the commitment to have a masonry fortification built to defend the city and port. The founding of Charles Town (Charleston) in 1670 by the British less than two-day's sail from St. Augustine further emphasized the need for a stronger fort. Construction of the fortress that would become the Castillo de San Marcos was begun in October 1672.

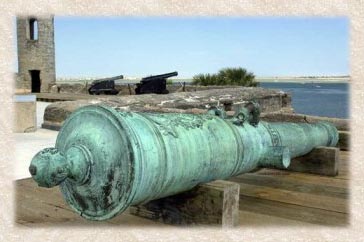

For this new fort the engineers chose to use a local stone called "coquina" (Co-KEY-Na). The name means "little shells" and that is exactly what the stone is made of-- little shellfish that died long ago, and their shells have now become bonded together to form the rock, a type of limestone. The coquina rock was quarried from Anastasia Island across the bay from the Castillo, and after rough shaping had been done, was ferried across to the construction site.

In a work area that was located where the Castillo parking lot is today, the stone masons sent here by the Crown from Havana labored to produce the blocks for the construction. The mortar to bond the blocks to each other was made on the construction site by baking oyster shells in kilns until they fell apart to a fine white powder called lime. The lime was then mixed with sand and fresh water to produce the mortar that still holds the Castillo together today. After 23 years of work, the Castillo was declared completed in 1695.

The Castillo had its first test when British forces under Governor James Moore of Charles Town (Charleston), Carolina laid siege to the city in early November, 1702. At the start of the siege the people of St. Augustine crowded into the Castillo to take shelter. Over 1200 civilians and 300 soldiers of the city would remain within the walls for almost two months as the British troops occupied the town.

The British cannon had little effect upon the soft coquina walls which merely absorbed the shock of the hits with little damage. The siege was finally broken by the arrival of a relief fleet from Havana that trapped the British ships within St. Augustine's harbor and forced the British to burn their ships to prevent their capture by the Spanish. As they withdrew from the area, the British put the city to the torch just as their countryman Sir Francis Drake had when he burned the city in 1586.

After the 1702 Siege, it was decided to improve the Castillo and fortifications of the city of St. Augustine itself. Construction work was begun on a new interior for the Castillo in 1738. The interior rooms were pulled out into the courtyard to make them deeper, and vaulted arch ceilings replaced the wooden roof to make the rooms bombproof to better protect the supplies stored inside. These vaulted ceilings also made it possible to mount heavy garrison guns all around the perimeter of the gundeck rather than just in the corner bastions as in the original design. The construction of the vaults made it necessary to raise the walls of the fortress from their original 26-foot height to the present 33-foot height.

In addition to changes to the Castillo, the Spanish began building walls around the city itself to protect their homes and property from being destroyed yet again. The northern wall running from the Castillo to the San Sebastian River is called the Cubo Line. It defended the land approach to the city from the north. The wall that protected the city's west and south sides was called the Rosario Line. At intervals along their lengths both of these defensive lines had redoubts, small palisaded platforms on which two cannon were mounted. (One of these, the Santo Domingo Redoubt, has been reconstructed at the corner of Orange and Codova Streets.)

In 1740 General James Edward Oglethorpe laid siege to St. Augustine from the newly established English Colony (in disputed territory) of Georgia. He established a blockade of the city harbor after successfully taking the small outpost forts of Fort San Diego, Fort Picolotta, and Fort Mose. (Eventually, Fort Mose would be retaken by the Spanish.)

Oglethorpe placed troops and cannon batteries on Anastasia Island to fire on the city and the Castillo. He hoped that a sustained bombardment and blockade of St. Augustine would cause the Governor of Florida, Manuel de Montiano, to surrender the city and fortress to the British. The English guns fired on the Castillo, but were unable to breach the walls.

The Spanish were able to successfully send a shallow-draft vessel down the river and out the Matanzas Inlet to sail down the coast to Cuba for supplies. When they returned from Cuba, the one British ship that was supposed to be guarding the Matanzas Inlet was gone. So they were able to bring the supplies to St. Augustine unopposed.

With British morale low due to the broken blockade, the defeat of the British forces holding Fort Mose, and the onset of hurricane season, Oglethorpe was unable to organize an assault on the Castillo. With the dawn of the 38th day of the siege, the citizens of St. Augustine saw that the British had withdrawn from the area.

Over the years, the distinctive star-shaped fort and surrounding moat have served several countries.

The British Period 1763 - 1784 The British Period 1763 - 1784

In 1763, Britain finally gained possession of St. Augustine and all of Florida, but not by taking St. Augustine. As a provision of the Treaty of Paris that ended the Seven Years War (The French and Indian War), Britain gained the Florida Territory in exchange for Havana and the Philippines, which the British had captured during the war. The British split Florida into an East Florida and a West Florida with St. Augustine the capital of East Florida and Pensacola the capital of West Florida. On July 21, 1763, the Spanish governor turned the Castillo over to the troops of King George III, and nearly all the Spanish citizens of the town moved to Cuba.

The British would make a number of small changes to the Castillo, including its name, which would now be Fort St. Mark. With the departure of the Spanish from Florida, the British felt no great need to maintain the Fort in first rate condition because they held the all of eastern North America. This outlook changed greatly with signs of rebellion being seen in the Thirteen Colonies to the north.

With the start of the American Revolution, St. Augustine enjoyed new importance as the capital of King George's loyal colony of East Florida. In early 1775, the changes in view of the Fort's new status could be seen. Repairs were made to the gates and the well, and housing in the Fort was increased by adding second floors in some of the rooms because it became regimental headquarters for the area. The British also improved the defenses of the city and its approaches. At this time, the old Spanish monastery on St. Francis Street was also turned into a barracks to house the influx of British soldiers. Today, this building is still in the hands of the military as the headquarters of the Florida National Guard.

Castillo de San Marcos Virtual Tour

As a foreshadowing of later activities, the Fort and St. Augustine also served as a prison for a few patriots who had been captured in Charleston, including Christopher Gadsen, the Lieutenant-governor of North Carolina, and three signers of the Declaration of Independence--Edward Rutledge, Thomas Hayward, and Charles Pinckney.

As the Revolution raged on, Spain came to the unofficial aid of the American colonies by sending money, weapons, medicine, and military supplies. When Spain declared war on Britain in 1779, Bernardo de Gálvez, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, immediately attacked and captured the British forts along the southern Mississippi River. Then he moved against Mobile in British West Florida and captured it as well. The next target was Pensacola, and in two months of heavy fighting, it too fell. By keeping the British occupied in the Gulf of Mexico, the Spanish kept the British from sending troops and supplies to support their efforts against the thirteen colonies, and thus they played an enormous part in the success of the Americans in their war for independence.

Bernardo de Gálvez was the only officer on any side in the Revolution who came out undefeated. The Battle of Pensacola was among the longest and hardest battles of the American Revolution. Yet, this remarkable general is relatively unknown. Only a statue in Washington, DC and one in New Orleans, and a city in Texas (Galveston) stand in tribute to this man who helped win the American Revolution.

At the end of the war, the Second Treaty of Paris returned Florida to Spain. On July 12, 1784, Spanish troops returned to St. Augustine.

The Second Spanish Period 1784 - 1821 The Second Spanish Period 1784 - 1821

With Spain's return to St. Augustine, the Fort had its name changed back to the Castillo de San Marcos. The Spanish soon discovered that Florida had changed markedly since 1763, however. Border problems of the past were now greatly increased by the fact that runaway slaves were coming into Florida to be welcomed by the Seminole Indians. Also, the population of Florida had changed. Few of the Spanish returned from Cuba, and many of the British who had homes and property from the British period stayed in Florida. Some of these were wealthy plantation owners, but many were ruffians and scoundrels who were now calling Florida their home base.

In spite of these challenges and coupled with unrest in her colonies in South America, Spain continued the reinforcement of the new defenses built by the British and the upkeep of the Castillo, including the rebuilding of the City Gates in 1808. Nevertheless, Spain's days in Florida were coming to an end. On July 10, 1821, after heavy pressure from the US Government and numerous other pressures on the Empire, Spain ceded Florida to the United States of America, ending 235 years of Spanish colonization.

The First American Period 1821 - 1861 The First American Period 1821 - 1861

On their arrival in St. Augustine, the Americans changed the name of the Spanish Castillo to Fort Marion, in honor of General Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox" of Revolutionary War fame. However, structurally little of the fortification was changed. The old storerooms with their heavy doors and barred windows were converted to prison cells. In the 1840s, army engineers turned the east moat into a water battery, part of the American Coastal Defense System, and improved the glacis hill around the Fort.

During the Second Seminole War, Seminole Indians were jailed within the Fort, among them Osceola in 1837. Several of them managed to escape, but Osceola was not among them. Already in ill health, he was sent to Fort Moultrie in Charleston where he died in January 1838.

The Confederate Period 1861-1862 The Confederate Period 1861-1862

In 1845, Florida became a state in the Union, but would remain so only until December of 1860 when she joined other Southern states to form the Confederate States of America and entered the ensuing American Civil War.

The federal troops had been withdrawn from Fort Marion leaving only a solitary sergeant at the fort as caretaker. In January 1861 the Confederates marched into St. Augustine and demanded that the sergeant surrender the fort to them. He said that it was government property, and he would need to get a receipt for it. This was done, and Fort Marion was turned over to the Confederacy without a shot. Most of the artillery was then sent away to other Confederate forts leaving Fort Marion nearly defenseless.

The Second American Period 1862 - 1900 The Second American Period 1862 - 1900

The Fort came back into Union hands on March 11, 1862 after the USS WABASH, a Union gunboat, took the city and Fort without firing a shot when it found that Confederate forces had evacuated the area and the local authorities were willing to surrender to preserve the town.

During this Second American Period, Fort Marion was mostly used as a military prison. In the 1870s seventy-four Indians from the Great Plains-- Kiowa, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Arapaho-- captured in the west during America's push toward her "Manifest Destiny", were imprisoned in Fort Marion for three years. Ten years later Apache were also captured and brought east. This time, most of the men, including Geronimo, were imprisoned at Fort Pickens in Pensacola, and the women and children were sent on to Fort Marion.

During the Spanish American War in 1898, almost 200 court-martialed deserters from the American Army were imprisoned within its walls. With the end of the 19th century, however, the Fort finally completed its long tour of duty. It was removed from the rolls of active bases in 1900, after serving under five flags over 205 years. Fort Marion was named a National Monument in 1924. In 1933 it was transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service, and in 1942, Congress restored the name "Castillo de San Marcos" in honor of its long Spanish heritage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|