Skip to comments.

[Flashback] On This Day In History: Ensisheim Meteorite Fell To Earth – On Nov 7, 1492

AncientPages.com ^

| November 7, 2016

| editors / unattributed

Posted on 08/02/2025 7:14:52 AM PDT by SunkenCiv

On November 7, 1492, the Ensisheim meteorite was observed to fall in a wheat field outside the walled town of Ensisheim in then Alsace, Further Austria (now France).

It was a stony, triangular-shaped meteorite weighing 127 kilograms. The object can still be seen in Ensisheim's Museum, the sixteenth-century Musée de la Régence.

Upon impact, the meteorite created a 1-meter (3 ft 3 in) deep hole. Its fall through the Earth's atmosphere was witnessed at a distance of up to 150 kilometers from where it eventually landed.

People living in neighboring areas gathered at the location to raise the meteorite from its impact hole. They began removing pieces of the meteorite, considered a sign of good luck from God. Many of the fragments later ended up in museums around the world.

According to sources, King Maximilian of Austria heard of the stone falling from the sky and decided to look at it. At the time, he was engaged in local battles with the French and believed that the fall was a sign from God, predicting his upcoming military victories.

After removing a piece of meteorite for himself, Maximilian declared that the remains should be kept in the church forever.

The stone remained in the parish church until the French revolution. Later, it was placed in a museum in nearby Colmar by French revolutionaries. French scientists also removed some pieces of the meteorite for further study.

The meteorite was returned to the church but had lost much of its mass by this time. Eventually, the remaining specimen, a rounded gray mass weighing only 55 kg, can be seen today at Ensisheim resting in an elegant case in the middle of the main hall of the Regency Palace...

(Excerpt) Read more at ancientpages.com ...

TOPICS: Astronomy; History; Science; Travel

KEYWORDS: 14921107; alsace; astronomy; austria; catastrophism; ensisheim; france; godsgravesglyphs; history; maximilian; meteor; meteorite; meteorites; meteors; science

Picture this: you live in the town of L'Aigle in Normandy, France. You're just going about your business on this day in 1803, when suddenly, rocks start to fall from the sky.

You'd notice, right? Well, it was the presence of a townful of witnesses to more than 3,000 stones falling from the sky that finally helped scientists confirm that meteorites came from space.

Although writing about meteorites goes even farther back than the Romans, writes French researcher Matthieu Gounelle, prior to the late 1700s nobody thought of them as something that needed scientific explanation. Like rains of less likely substances -- including "blood, milk, wool, flesh and gore," according to historian Ursula Marvin -- eighteenth-century rationalists with their fancy new scientific outlook thought the stories of rains of iron rocks weren't real.

A physicist named Ernst Chladni had published a book in 1794 suggesting that meteorites came from space. Chladni was hesitant to publish, writes Marvin, because he knew that he was "gainsaying 2,000 years of wisdom, inherited from Aristotle and confirmed by Isaac Newton, that no small bodies exist in space beyond the Moon."

...But after the meteorites fell in l'Aigle, Jean-Baptise Biot, a physicist, went to analyze the event. Biot was a scientist whose resume also includes the first scientific balloon flight and pioneering work in the field of saccharimetry (a way to analyze sugar solutions)...

"Biot distinguished two kinds of evidence of an extraterrestrial origin of the stones," Gounelle writes. First, the kind of stone that had fallen was totally different than anything else available locally -- but it was similar to the stone from the Barbotan meteor fall in 1790. "The foundries, the factories, the mines of the surroundings I have visited, have nothing in their products, nor in their slag that have with these substances any relation," Biot wrote.Scientists Didn't Believe in Meteorites Until 1803 | Kat Eschner | Smithsonian Magazine | April 26, 2017

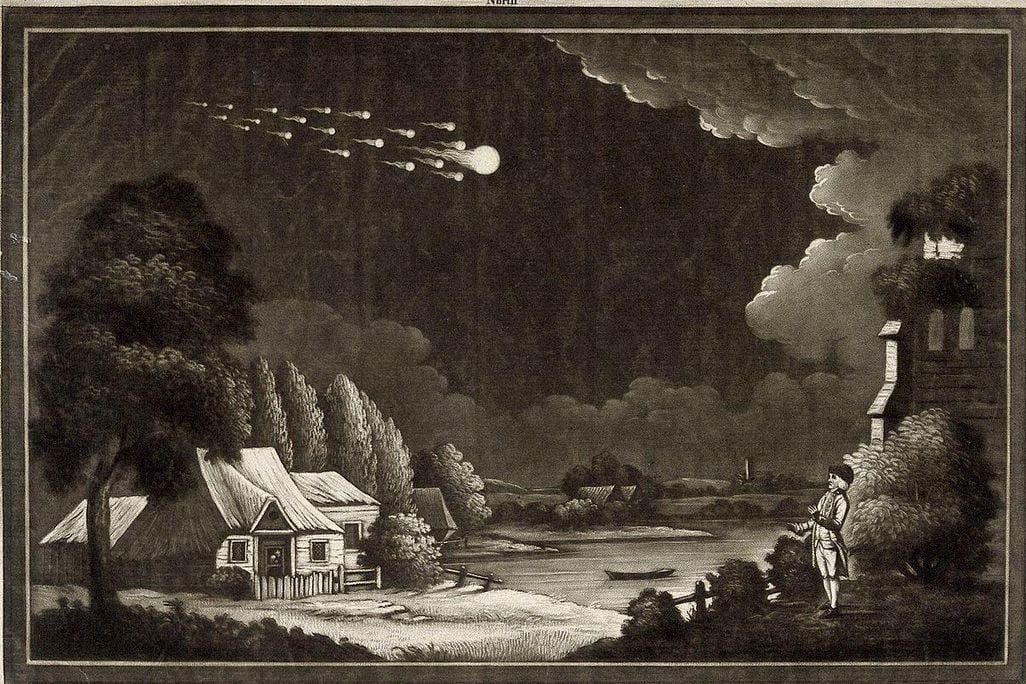

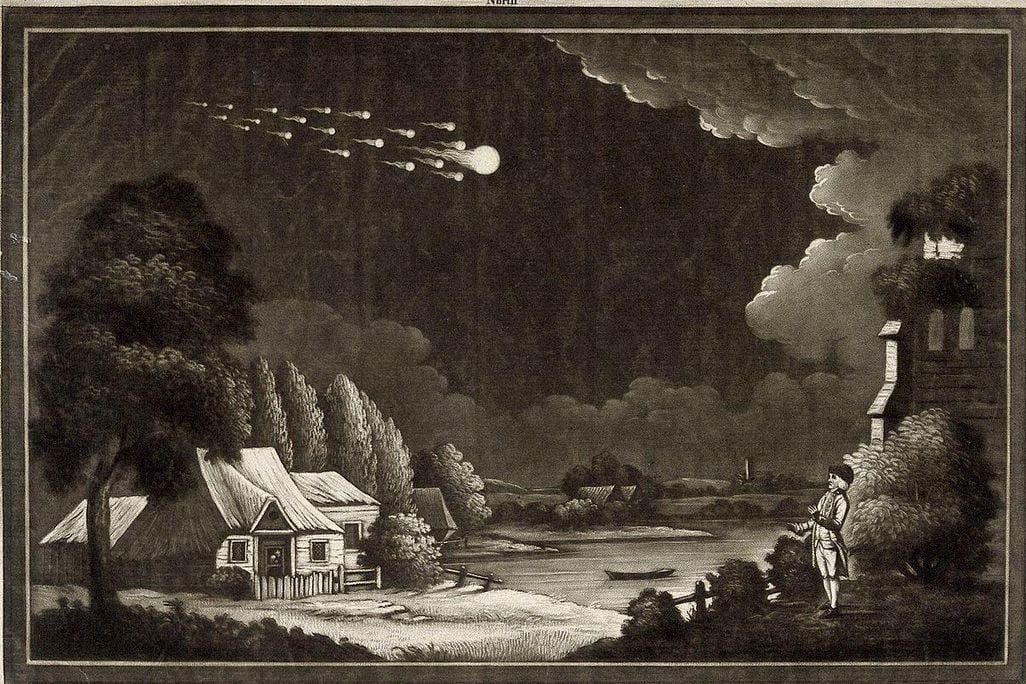

An artist's rendering of a meteor passing over the British Isles in 1783. Unlike the L'Aigle meteor a few decades later, the meteorites from this event were not witnessed falling to the ground, and thus meteorites remained a scientific mystery for another 20 years.Wellcome Images

1

posted on

08/02/2025 7:14:52 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

To: 75thOVI; Abathar; agrace; aimhigh; Alice in Wonderland; AnalogReigns; AndrewC; aragorn; ...

aristotle stones can't fall from the sky [snip] Aristotle believed that stones could not fall from the sky because he thought the heavens were perfect and could not have loose pieces floating around to fall to Earth. [/snip] | Brave AI result

2

posted on

08/02/2025 7:16:34 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: StayAt HomeMother; Ernest_at_the_Beach; 1ofmanyfree; 21twelve; 24Karet; 2ndDivisionVet; 31R1O; ...

3

posted on

08/02/2025 7:17:20 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: SunkenCiv

4

posted on

08/02/2025 7:25:35 AM PDT

by

bgill

To: SunkenCiv

Christopher Columbus also discovered America in 1492 - it was quite the year!

5

posted on

08/02/2025 7:28:45 AM PDT

by

Ken522

To: SunkenCiv

6

posted on

08/02/2025 7:34:52 AM PDT

by

Fido969

To: Ken522

but no one in Europe knew about his discoveries until 1493

7

posted on

08/02/2025 7:41:43 AM PDT

by

ChronicMA

To: SunkenCiv

The meteorite was returned to the church but had lost much of its mass by this time. Um…..how does this happen with a rock?

8

posted on

08/02/2025 7:56:43 AM PDT

by

DoodleBob

(Gravity's waiting period is about 9.8 m/s²)

To: Ken522

Christopher Columbus also discovered America in 1492 - it was quite the year!

The 15th century itself set the modern world: French & English statehood, printing press, rise of Ottomans, Reconquista in Spain, the Caravel and European transoceanic trade & conquest (also the Ming fleet), Hussite Rebellion, Devotio Moderna, Aztec rise, Songhai rise (slave trade), matchlock trigger for firearms, double-entry bookkeeping & modern banking bills of exchange, industrial advances, esp. mills and furnaces, and, of course Da Vinci.

9

posted on

08/02/2025 8:02:44 AM PDT

by

nicollo

(Trump beat the cheat! )

To: DoodleBob

How does a rock go from 122kg to 59kg? The USPS hadn’t been invented, must have been FedEx damaged in shipment. Lucky it even made it to earth...

10

posted on

08/02/2025 8:18:46 AM PDT

by

Ikeon

(Saying f**k to a 5 y.o. gets less response than saying n!$$er to a full grown black person. Explain?)

To: Fido969

11

posted on

08/02/2025 8:23:49 AM PDT

by

bwest

To: DoodleBob

The article says various people and institutions kept chipping away samples from the stony meteorite, reducing its original 127 kilogram mass to 55 before it was finally returned to the church. (After French revolutionaries had removed it.) Its density should have remained the same, if it was homogenous in composition throughout, if that’s what you mean.

Aside: Through gifts and thefts, only a fraction of the rocks the Apollo missions brought back from the moon remain in NASA’s keeping.

12

posted on

08/02/2025 8:31:55 AM PDT

by

BradyLS

(DO NOT FEED THE BEARS!)

To: SunkenCiv

“I would rather believe that two Yankee professors would lie than that stones would fall from heaven.” - attributed to Thomas Jefferson, 1807

13

posted on

08/02/2025 8:45:44 AM PDT

by

KarlInOhio

(I refuse to call the left "progressive" because I do not see slavery to the government as progress.)

To: DoodleBob

Uh, people kept chipping off chunks of it.

14

posted on

08/02/2025 9:18:09 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: KarlInOhio

Brave AI: [snip] According to historical records, Jefferson’s reaction to the meteorite incident was cautious, but not as dismissive as the quote suggests. He wrote to Daniel Salmon on 15 February 1808, expressing that while it was difficult to explain how a stone could have come into its position, it was not easier to explain how it got into the clouds from which it was supposed to have fallen. Jefferson emphasized the need for evidence to support such extraordinary claims. [/snip]

(turns out, use of the phrase “extraordinary claims” is in fact the only indisputably extraordinary claim)

15

posted on

08/02/2025 9:25:30 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: bwest; Fido969

16

posted on

08/02/2025 9:26:57 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: bgill

The trick is to have it miss you.

17

posted on

08/02/2025 9:27:24 AM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(The Demagogic Party is a collection of violent, rival street gangs.)

To: Ken522

In 1482, Ensisheim sailed the sky, um, blue?

To: SunkenCiv

Oh, I get that part.

But the syntax chosen by the writer makes it like a natural, sort-of decompositional situation.

19

posted on

08/02/2025 2:23:20 PM PDT

by

DoodleBob

(Gravity's waiting period is about 9.8 m/s²)

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson