Posted on 11/02/2003 4:11:21 PM PST by blam

Immigrants from the Other Side?

According to the Clovis-First theory, for decades the gospel preached by authorities on the peopling of the Americas, the first Americans walked across the Bering Land Bridge from Asia about 12,000 years ago, and after finding a corridor through the Cordilleran Ice Sheet--admittedly it wasn't an easy trip and the timing was tricky--descended into temperate North America. We know them by their classic fluted points, unlike any others in the world, they left at campsites on their journey south to populate Central and South America.

[~ 45:l ~] There have been variations of the basic theory. The Greenberg hypothesis asserts that not one but three waves of Asian travelers crossed on foot, each founding a different linguistic family. Recently anthropologist C. Loring Brace of the University of Michigan revealed the results of his study, which postulates that two crossings, one on foot 15,000 years ago, the other by water 10,000 years later, gave rise to two linguistically unique peoples ("New Study," MT 16-4). Asians again.

Even before 1997, when a panel of authorities inspected the Monte Verde site in Chile and conceded that radiocarbon-dated evidence of human occupation predates the earliest Clovis sites in North America by 1,000 years (which makes it difficult to defend the theory of a north-to-south population movement), Smithsonian archaeologist Dennis Stanford was looking in a different direction for the origin of the first people that entered America. He was looking not west to Asia, but east to Europe.

Dropping a cold trail for a warmer one

Dr. Stanford is no maverick. His mentors were luminaries in American peopling studies: the late Marie Wormington, Curator of Archaeology at the Denver Museum of Natural History for 31 years and author of classic texts on early Americans, whose seminal field work in the Southwest in the 1930s shaped the practice for those who followed her; and C. Vance Haynes, Jr. of the University of Arizona, who probably more than any other person has defined the Clovis culture (and who today continues to reserve judgment on the validity of Tom Dillehay's purported pre-Clovis Monte Verde site). Stanford, for much of his professional life, was an enthusiastic Clovis-First advocate.

[~ 46:r ~] What made him turn away from the Bering route and look elsewhere for the first migration? His thinking evolved over three decades. In the '60s Stanford, like most of his colleagues, believed that Clovis came from Asia. It wasn't until the '70s that he began to believe that Clovis was a New World development and that evidence of pre-Clovis would be found in the Arctic. "But I wasn't seeing evidence," he recalls, "and after a while it started not to make sense. Everything I found in Alaska that was fluted was post-Clovis in age." There was no technology he considered pre-Clovis. He hoped at the time that once Siberia was opened up to Western scientists we would find the missing evidence. But the end of the Cold War didn't provide the solution for Stanford and his co-theorist, lithics expert Bruce Bradley. Stanford and Dr. Bradley independently looked at the evidence and arrived at the same conclusion. They inspected late-Pleistocene sites and scoured museum collections in Siberia, Russia, and northern China, seeking pre-Clovis technology. Instead, what they found was a totally different method of making tools and weapons.

The Clovis fluted point is knapped from stone, flaked on both sides (bifacial) and shaped into a beautiful thin, flat killing instrument; the base is thinned and relieved into a concave recess so that the point can be securely hafted onto a foreshaft or shaft. (See "Lithic Caches" in this issue for a photo of spectacular examples of Clovis points.) The Asian upper-Paleolithic weapons that Stanford and Bradley found, however, were made using a microblade technology, where tiny blades struck from wedge-shaped cores of stone were inset into long, narrow rods of bone, antler, or ivory. When Far East craftsmen tried to make bifacial tools, the result was relatively crude implements (quite thick in cross section, compared with exquisitely thin Clovis points) and frequently bi-pointed. Stanford and Bradley suspect the Asian bifaces were knives instead of projectile points.

True, they found assemblages containing bifaces and large blade cores. But those sites are in the Trans-Baikal region of central Asia--about 6,000 miles from Alaska--and date to 10,000 years before Clovis. To Bradley they appear to belong to the Streletskayan technology of the Eurasian Plain and not to the Far East.

[~ 47:l ~] Nowhere in Asia did Stanford and Bradley find the ancestor of the Clovis point. They reasoned that if the first immigrants were Asian, they must have brought with them their inset-microblade manufacturing process, in which case there must exist evidence of a transition to Clovis technology. So far, however, nothing resembling an intermediate form between inset microblades and a knapped biface has been found in North America.

Stuck at a dead end, Stanford and Bradley took up a fresh trail. The roots of Clovis, they reasoned, must lie in the Paleolithic Old World outside of Asia. They took up the search for a parent technology that specialized in making thin, flat bifacial projectile points, knives and other biface implements, and other artifacts of stone and bone similar to those of the Clovis culture. They didn't demand of the candidate that it precisely match Clovis technology, only that it exhibit features that could be reasonably interpreted as pre-Clovis. They found only one Paleolithic culture whose technology met their criteria, suggested by Nels Nelson of the American Museum of Natural History early in the 20th century and later by University of Arizona archaeologist Art Jelinek in an article published in 1971 in Arctic Anthropology: the Solutrean people. Named for the French town of Solutré, the culture spread across much of France and the Iberian Peninsula. Stanford and Bradley look to northern Spain and southwestern France for the people who might have carried pre-Clovis technology across the Atlantic.

Newest members in a family with a long history

Whatever problems beset European archaeologists, they don't suffer from a dearth of evidence of early human occupations. The Mousterian culture of the Neanderthals, for example, has been traced back 250,000 years. The Neanderthals made tools of stone, some of them eye-catching even today, but they weren't innovators. For more than 100,000 years they continued to reproduce the same tools using the same pattern, never varying. Says French prehistorian François Bordes, "They made beautiful tools stupidly."

[~ 48:r ~] About 30,000 years ago, at the start of the upper Paleolithic, Neanderthals seem to disappear. Their place is taken by Cro-Magnon man, modern humans who brought with them a culture probably developed in Asia. The Aurignacian period ushered in the beginnings of communal activity and living. People hunted and fished in organized groups, lived in the first man-made shelters, wore sewn clothing, and left the first evidence of belief in magic and the supernatural. They were imaginative artists who decorated cave walls with their paintings and carved ornaments of bone, horn, and ivory. Moreover, they crafted new kinds of tools, including projectile points, of different materials including flint and obsidian.

We find the first evidence about 25,000 years ago of the Gravettians, whose range eventually extended from Russia to Spain. They brought west with them improved methods of knapping spear tips of stone, making them more lethal and easier to sharpen, and the atlatl, a spear thrower that effectively lengthens the hunter's arm and thereby increases the power and range of the thrown spear. Recent finds in Czechoslovakia are convincing evidence that the Gravettians were also weavers, not just of basketry and textiles, but also of nets for snaring small animals. Change was happening faster and faster in Europe, each group of newcomers building on the foundation laid by the existing population.

Enter killers with a flair for art

About 20,000 years ago a new group arrived, some scholars think from the east, others from North Africa. They took up residence in caves and rockshelters in France and Spain--and western Europe was never the same again. We call them the Solutreans. They were highly efficient hunters, the likes of whom probably weren't seen again until the white slaughterers of the American buffalo in the 19th century. Estimates of the number of wild horses killed in the upper Paleolithic at Solutré alone range from 30,000 to 100,000. Full bellies gave them leisure time, which they used to decorate the walls of their caves with fabulous surrealistic paintings of bison and horses and ibex that continue to awe us today. They were carvers, too, for art's sake. In Solutrean sites we find carved limestone tablets--at one site in Spain there are stacks of hundreds. Stanford describes them as "3 to 6 inches long, 3 inches wide, and half an inch thick. The design, sometimes zoomorphic, sometimes geomorphic, is engraved on one side or both." They weren't drilled and made into pendants. They don't do anything. Perhaps they have religious significance. Or perhaps they just are.

What made the Solutreans deadly efficient hunters was their unprecedented skill at fashioning tools and weapons from stone. In the 4,000 years of their supremacy we can see their knapping creations evolve from unifacial points (later reappearing as the willow-leaf point, unifacial again, but of extraordinary delicacy and fineness) to bifacial laurel-leaf points and blades.

[~ 49:l ~] "They had the only upper-Paleolithic biface technology going in Western Europe," Stanford points out. They were the first to heat-treat flint, and the first to use pressure flaking--removing flakes by pressing with a hardwood or antler tool, rather than by striking with another stone. "In northern Spain, their technology produced biface projectile points with concave bases that are basally thinned," he notes, not bothering to say he could just as well be describing Clovis points. The pressure flakes Solutrean knappers removed are so long it's almost a fluting technique--"almost," he's careful to say, but not quite.

The parallels between Solutrean and Clovis flintknapping techniques seem endless. The core technology, "the way they were knocking off big blades and setting up their core platforms," he explains, "is very similar to the Clovis technique, if not identical." They perfected the outre passé--overshot--flaking technique later seen in Clovis, which removes a flake across the entire face of the tool from margin to margin. It's a complicated procedure, he emphasizes, that has to be set up and steps followed precisely in order to detach regular flakes predictably. When you see outre passé flaking in other cultures, you're looking at a knapper's mistake. The Solutreans, though, set up platforms and followed the technique through to the end, exactly as we see in Clovis. "No one else in the world does that," Stanford insists. "There is very little in Clovis--in fact, nothing--that is not found in Solutrean technology," he declares.

Archaeologist Kenneth Tankersley of Kent State University seconds Stanford and Bradley's opinion: "There are only two places in the world and two times that this technology appears--Solutrean and Clovis."

[~ 50:r ~] On and on the similarities pile up. We find carved tablets in Clovis sites remarkably similar to Solutrean specimens. Both cultures cached toolstone and finished implements. (See "Lithic Caches" in this issue.) Stanford and Bradley know of about 20 instances of caches at Solutrean sites; in North America, by comparison, according to Stanford, "we're up to about nine or ten." Just like Clovis knappers, Solutreans used flakes detached by outre passé to make scrapers and knives. Clovis bone projectile points bear an uncanny resemblance to ones made by Solutreans. When French archaeologists saw the cast of a wrench used by Clovis craftsmen at the Murray Springs site in Arizona to straighten spear shafts, they declared it remarkably similar to one found at a Solutrean site.

In 1997 Stanford was invited by French archaeologists to bring specimens of Clovis tools and weapons to an exhibit at the museum of Solutré, organized by Anta Montet-White and Jack Hofman of the University of Kansas. It was on that trip in the summer of 1997 that Stanford, able to compare Solutrean and Clovis tools side by side, became confident he was looking at products of technologies so similar there was a high probability they were in fact historically related technologies--one culture--separated only by time and distance.

A tough mouthful for critics to swallow

Stanford and Bradley know it's asking a lot of their fellow archaeologists to accept the idea that the first immigrants set foot on the Atlantic seaboard of North America. Time and distance are indeed hurdles of considerable height. The Clovis and Solutrean cultures are separated in time by more than 4,000 years, in space by the Atlantic ocean--nearly 3,000 miles today.

[~ 51:l ~] When Stanford and Bradley are in a temporizing mood, they allow the possibility that the astonishing constellation of similarities that exist between Solutrean and Clovis technologies may be the result of independent invention, that bright chaps at two different times and at two different places on Earth may have hit on the same ideas--a lot of them--each by himself without outside influence. Indeed, Stanford is by no means an inflexible dogmatist. "It's very clear to me, at least," he is quick to state, "that we are looking at multiple migrations through a very long time period--of many peoples of many different ethnic origins, if you will, that came in at different times."

For the record, Stanford and Bradley say they push their theory "as the most parsimonious conclusion based on the best available data currently available." But if you talk to Dennis Stanford one-on-one about this particular migration that establishes the Solutrean-Clovis connection, he doesn't hedge. You quickly realize he is a self-assured scientist who is supremely confident that time will prove him right. Listen to his argument, and you have to allow that he has thought a great deal about every side of this theory.

Tackling the question of time

Setting aside for the time being the problem of how Solutreans crossed the Atlantic, and assuming it was a trip they could undertake and survive, the question then arises: Why don't we see signs of their presence in North America 4,000 years before Clovis?

[~ 52:r ~] But we do see evidence of them, Stanford and Bradley counter, at two sites. At Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, stratified deposits that predate Clovis by several thousand years--the lowest occupation level dates to 19,000 years ago--have yielded remains of basketry and lithic artifacts including blades and points, unfluted bifacial projectile points. Clovis-First proponents have contested the radiocarbon dates for nearly three decades now, asserting that radiocarbon dating samples may have been contaminated with coal particles or other carboniferous material carried by groundwater. Although geomorphologist Paul Goldberg of Boston University in 1999 declared unequivocally that "no trace of groundwater activity could be seen"--after minutely examining 25 samples from six layers at Meadowcroft--James Adovasio's labors still haven't received universal recognition.

Meadowcroft Rockshelter would stand as a one-of-a-kind perturbation in the archaeological record if not for the Cactus Hill site in eastern Virginia. The hill is the accumulation of windblown sand over many thousands of years, according to Joseph and Lynn McAvoy, whose private consulting firm, Nottoway River Survey, has been excavating side by side with the Archaeological Society of Virginia. What they've found is a continuum of human occupations dating backwards from the colonial period--witness a pipe stem and a sixpence piece dated 1696--to the Clovis culture. Below the Clovis level, above a bed of sterile clay, they found an assemblage of stone tools including blades and cores and thin bifacial points. Radiocarbon dates from a hearth and other features put human occupation at 15,000-17,000 RCYBP, or about 18,000 to 20,000 years ago. Artifacts from Cactus Hill share so many of the features of the Meadowcroft Rockshelter finds that Stanford and Bradley contend the two sites could be considered related technologies, or even two instances of the same one.

Unfortunately, just as at Meadowcroft Rockshelter, a cloud of skepticism hangs over the Cactus Hill site. Any number of agents--animals, looters, even intrusive roots--could have introduced old charcoal into layers containing younger artifacts, say the McAvoys' critics. They point to different samples from the same layer reporting different ages as corroboration of their concerns about contamination. This, despite the McAvoys' repeated protests that Yale University paleobotanist Lucinda McWeeney judged the anomalous dates to be nothing more than the result of young plants burrowing downward. There's absolutely nothing to show that older material was pushed upward, say the McAvoys . . . over and over again.

[~ 53:l ~] Stanford and Bradley confess themselves mpressed by the fit of the evidence found at Meadowcroft and Cactus Hill. Bifacial weapon tips, blades, and blade cores found at the sites are technologically very similar to Solutrean examples; the radiocarbon dates (if believed) dovetail nicely with the period of the Solutrean culture and fill in the 4,000-year gap. In a paper now in press, Stanford and Bradley deplore the inequity in disallowing evidence from Meadowcroft and Cactus Hill. Their statement is a model of restraint:

Must we wait until yet a third or fourth site is found before we can take this evidence seriously? Probably so. However, we believe that this same rigor of analysis demanded by scholars of these sites has not been applied to the Beringian sites that many consider ancestral Clovis; but it should be.

Supporting evidence from a different source

Archaeological evidence isn't the only weapon in Stanford and Bradley's armory. They point out discoveries in genetics by researchers at Emory University and the Universities of Rome and Hamburg. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is inherited exclusively from the mother, normally contains four markers called haplogroups, labeled A, B, C, and D. These four are shared by 95 percent of Native Americans. Recently, however, the genetics team identified a fifth haplogroup, called X, which is present in about 20,000 Native Americans and has also been found in several pre-Columbian populations. A most interesting fact is that haplogroup X is also present in European populations but absent from Asians. The geneticists' research suggests the marker may have existed in the Americas 12,000 to 34,000 years ago, which means it must have been introduced before Clovis. By whom? Stanford and Bradley's prime candidates are Solutreans.

Now, about that Atlantic crossing . . .

There's a curious paradox at work here. The aspect of Stanford and Bradley's theory their critics find hardest to accept, that anyone could have crossed the Atlantic Ocean 20,000 years ago, doesn't worry Stanford at all. What's more, he says he rarely finds a European scientist who considers the Atlantic an insurmountable obstacle to determined Solutreans. "They aren't like landlocked Americans," he says of his European counterparts.

[~ 54:r ~] Stanford argues from a position of logic, historical data, and common sense. "Everyone knows boats have been around for 50,000 years," he says. Long ago early people in different parts of the world developed the skills needed to navigate open seas. People on the Japanese mainland 29,000 years sailed to offshore islands and returned with obsidian, their preferred toolstone. "Common sense tells us," he concludes, "one leg of the round-trip journey had to be against the current or wind or both." The early Japanese obviously solved the problems of sailing to windward. So must have done ancient mariners in Greece, where 13,000 to 14,000 years ago they regularly sailed from the mainland to collect obsidian from the offshore island of Minos. Why, then, can't we credit the Solutreans, who mastered the working of stone and created stunning works of art, with the same caliber of resourcefulness and problem-solving skills?

Evidence abounds from recent years that the Atlantic Ocean can be crossed in watercraft a lot smaller and less sophisticated than a liner. In 1896 two Norwegians, Harboe and Samuelson, rowed from New York to Le Havre in a dory, which can hardly be considered a high-tech contrivance. In 1976 Irish scholar and explorer Tim Severin built the Brendan, named after and constructed according to records left by St. Brendan, a sixth-century Irish monk, who (if you can sort myth from fact) sailed from Ireland to America. Severin built his curragh of 49 ox hides stitched to a wooden frame and waterproofed with sheep tallow, just as St. Brendan is said to have built his craft, and followed the same route described by the saint: north to the Faroes, then riding east-west currents that sweep past Iceland and Greenland. He landed at Newfoundland after a harrowing voyage--his first sail in a leather-skin boat.

There's also anecdotal evidence that amazing voyages are sometimes made by accident. The BBC in 1999 related the story of five African fishermen who were caught in a storm. In the grueling journey that followed, two died, but three eventually found themselves in South America. Dennis Stanford recalls an incident when he was working in Alaska. It was in the '60s, pre-Pipeline days, when, as he puts it, "Eskimos were still pretty much Eskimos." Stanford hunted and fished with them. "Sure," he says, "it's dangerous. You can freeze to death or get lost, but the Eskimos had been doing it for thousands of years." One day at Point Barrow he got word that two natives wanted to see him--urgently. The urgency, it turned out, was because they had heard he was visiting and wanted to talk to him about New York, to tell him what a strange city it was and how much they had enjoyed it. He asked the natural question: How in the world had they managed to see New York City? They told him their amazing story that had begun one spring, when they were hunting on the frozen Arctic Ocean. The ice broke up sooner than expected, and they found themselves adrift on an ice island. It floated around the North Pole and eventually drifted south east of Greenland. They were floating between Greenland and Iceland when the Iceland Coast Guard picked them up. They had spent the whole summer drifting. They weren't in despair, but they did admit they were starting to get a little worried because the island was melting away under their feet. They got a trip home, with a stopover in New York on the way--having made nearly a complete circumpolar voyage with minimal survival equipment.

No strangers to their marine environment

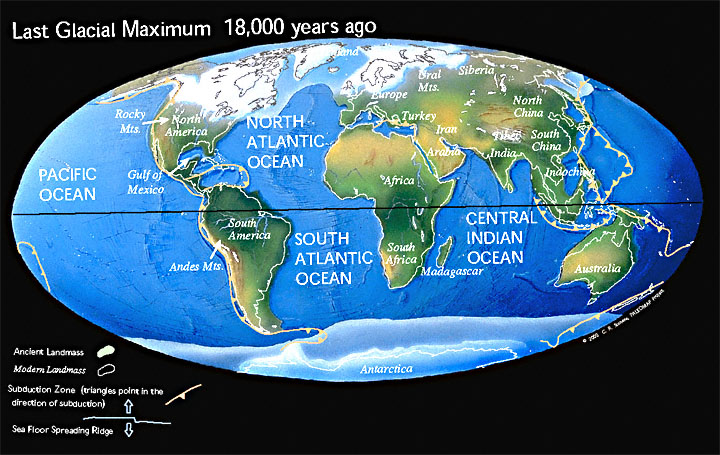

Stanford's Eskimo friends survived a voyage most of us would consider unthinkable because they were adapted to their environment. Stanford has no doubt that Solutreans, too, learned to adapt to conditions in Europe in the Last Glacial Maximum. It was a stressful time for the land and its creatures. Low temperatures, a short growing season, and scarce rainfall displaced animals and people from the interior to fertile areas along rivers and the coastline of southwestern Europe. People learned to exploit alternative resources found along estuaries and the beach, for if the Ice Age was a time of hardscrabble existence on land, it was a time of abundance along the sea. At the time of the Middle Solutrean, when Stanford and Bradley believe the Atlantic crossings were made, winter sea ice formed as far south as the Bay of Biscay. With the ice came marine life that thrived in the ice-edge habitats, including fish, sea mammals, and birds. Today Arctic waters, not the tropics, are the food factories of the oceans, where plankton and krill multiply in abundance. The same was true of the Last Glacial Maximum. Samples of deep-sea cores indicate that foraminifers, one-celled animals (their accumulated shells form the White Cliffs of Dover), found temperature and salinity quite tolerable. Presence of this basis of the food chain would have insured in turn the presence of abundant numbers of fish, and the sea mammals and birds that fed on them. "Remember," Stanford says, "that Solutreans were at least in part shore dwellers. At the time of maximum glaciation the sea level was down 130 m [about 425 ft]. They were living on the edge of the ocean. You can't tell me they didn't figure out how to exploit that really rich subarctic water that was coming into the Bay of Biscay and along the coast."

[~ 55:l ~] Stanford is confident that Solutreans adapted to a maritime way of life. Surely they built boats, almost certainly skin boats, the universal craft built by primitive people who have ready access to animals for leather and only rudimentary tools for working wood. The problem is that leather and wood are highly perishable materials. Stanford resigned himself to the probability that we would never find direct evidence to substantiate the Solutreans' seagoing skills.

Then in 1992 Le Cosquer cave was discovered near Marseilles by diver Henri Cosquer. Today the cave mouth lies 100 ft below the surface; in Solutrean times it would have been on a hillside 300 ft high several miles inland from the Mediterranean. The cave walls are profusely decorated with outlined human hands, complex geometric designs, and paintings and engravings of animals including horses, ibex, auks, and Megaloceros, the great Irish elk with 100-pound antlers spanning 11 ft. Penguins are represented, too, which speaks volumes about the diversity of game available along Pleistocene shores. But what most interests Stanford and Bradley is that among the rock art figures are depictions that may be seals impaled by harpoons as well as possible flounder and halibut--deep-sea fish! Clearly Solutreans learned how to exploit marine resources.

Steppingstones across the Atlantic

We haven't yet found the limits of the Solutreans' hunting forays and explorations. It appears they established camps on the pleniglacial beaches and estuaries of northern Spain; if so, they could easily have ranged as far north as the south coast of Ice Age Ireland. A site found in an unglaciated area of the British Isles was originally thought to be of Solutrean age; on a trip to England last spring, Stanford learned the site has been redated and is now considered even older, a pre-Solutrean occupation.

It requires only a small leap of Stanford's imagination to envision a voyage, perhaps intended, perhaps accidental, beyond areas already explored by the Solutreans. "Tell me," he says, "after 4,000 years of casting their eyes at the water, that all those hunters along the coast didn't understand weather and waves and ice. In the spring, when the ice broke up, they could put out to sea in flexible skin boats, along with huge ice islands, following the current." His critics argue that even the Titanic couldn't make the crossing. He turns the argument against them, for the same iceberg that sank the Titanic would have provided a safe haven for seafarers caught in a storm. They could have pulled their boats up onto it and huddled under the inverted hulls for shelter. For that matter, the permanent ice that bridged the Atlantic, and the sea ice that extended further south in winter, would have provided limitless opportunities to haul out their boats and hunt ice-edge game.

It was only a question of time, in Stanford's opinion, until a boatload of bold Solutreans would have traveled the mere 1,200 to 1,500 miles to the Grand Banks, which, because of the greatly lowered sea level, was the northeasternmost extension of North America. There they would have found fisheries and game animals prolific beyond their wildest dreams. They would have returned to this frozen land of plenty again and again . . . until one day an inquisitive Solutrean wondered if there wasn't some place with even more fish and game just over the western horizon. The distance from the Grand Banks to the coast of glacial North America is so short it makes the final leg of the journey inevitable.

Once here, they quite understandably would have settled initially along the shore and rivers--having just crossed the Atlantic, they would have been comfortable near water and probably uncomfortable away from it. Of course, if their first settlements were at the water's edge, they now lie under fathoms of water. Gradually, however, they would have turned their exploring instincts inland. Meadowcroft Rockshelter and Cactus Hill, Stanford and Bradley believe, just happen to be the only evidence we've found so far of the sires of Clovis.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How to contact the principal of this article: Dennis Stanford Smithsonian Institution MNH-304 Washington, D.C. 20560 e-mail: stanford.dennis@nmnh.si.edu

I agree, including Spirit Cave Man. We're still waiting for the judge to rule on Kennewick Man...I read somewhere that the ruling is expected in weeks.

I'm beginning to think the Kennewick Man type will be different from the discoveries on the east coast of the US, such as Windover, Meadowcroft and Topper.

They may all originate from a common population but seperated by thousands of years. I think one group took the Siberian route and one (or more groups) took the Atlantic route. I think the Kennewick Man type will prove to be the oldest and most dissimilar. Just an opinion.

Haven't you overlooked the Jomon and Ainu groups? (...and more recently (2-4,000 years ago) the Xiongnu, Han and Hakka Chinese)

Another thing, about early explorers, they weren't necesarily on a mission to find, log and report back. They would probably be well prepared to move to a new land and stay there, or move even farther away. Even if carried to the caribbean accidentally, they had most of what they needed to survive at hand. What I think would add to this debate is a discussion of their cultural tendencies when hunting and fishing. If they did so as families, they would have even less reason to return to their homelands once they found a nice place to set up.

You mean "rising." England is a perfect example, It's going like a see-saw.

There are about 10,000 alive today

There was a mixing of the Chinese (Han) and these people thousands of years ago in the Tarim basin. This mixing produced, I believe, the Scythians, Xiongnu and the Hakka. The Hakka migrated all the way across China into south China, Korea and Japan. Their records and legends indicate that during their migration anyone with Caucasian features were executed. (many tried to conceal their appearance)

I also believe that some mixing of all these groups later produced the Huns.( also with possibly an Iranian element.)

An excellent book to read on this subject is The Tarim Mummies by Victor Mair.

"Genetically speaking, some Hakka people have clearly inherited some non-Han features such as wavy hair and high nose bridge."

Further north, yes, it is rising. Maybe we are saying the same thing differently?

See all that ice in the north? It was so heavy that it weighted everything down and pushed up areas in the south (like a see-saw). Now, the south is sinking and the north is rising.

No problem, Southern roots are good.

Remember this? It's coral strata from the Pacific Coast off San Francisco.

I would bet that the numbers for the depthe of the Pacific seabed should be adjusted upward to correct for the uplift on the edge of the Pacific Plate (there are credible estimates that the Santa Cruz Mountains would be twice as high as Everest but for the rate of erosion), so perhaps your 450 ft estimate isn't far off.

Highway 17 would sure be a lot more exciting. We still have much to learn.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.