I'm the A.F. flunky in the pic, standing at "present arms".

Posted on 12/04/2008 7:55:40 PM PST by shove_it

Written By Those Who Were There

[...]

This JFK Funeral history project was begun in order to record and preserve this valuable information while it was still available. The four organizers of the Project learned from reading the various accounts they were assembling into this collection, that each individual participant in the State Funeral saw only a small piece of the whole event, and by collecting numerous individual pieces, the whole picture becomes visible. No single person witnessed the entire funeral.

This unique collection of personal memoirs is intended to portray the events of the State Funeral as seen through the eyes of those who were there. There are 20 individual accounts of the Kennedy funeral in this collection. Many of the accounts contain original “insider information" not found in other sources. In some cases, different people remember the same event differently. Different perspectives, compounded by imprecise memories after the passage of 44 years, sometimes result in having conflicting accounts of the same incident.

[...]

No two people see the same event alike. Instead of diminishing the value of the collection, these historical inconsistencies enhance and enrich it. In those instances where different accounts contain conflicting versions of the same event, the Editors have inserted a comment in each account referring the reader to the other versions.We make no attempt to determine which version is correct. Much of the information contained in these personal memoirs cannot be found anywhere else.

This collection is truly unique.Organized and Edited by Four Who Were There: Kenneth S. Pond, Thomas F. Reid, Edward M. Gripkey, James W. McElroy.

2008 Thomas F. Reid All rights reserved.

Any FReepers having expertise in the production of documentary videos and an interest in this subject, FReep mail me and I'll put you in touch with Tom Reid as he would be grateful for suggestions on producing a documentary DVD of this major historical event.

Having received permission from Tom Reid, I'm posting eye witness accounts of three former Old Guard soldiers which you will, hopefully, find most interesting ......

WALKING HORSE FOR PRESIDENT KENNEDY Arthur A. Carlson

When President Kennedy was assassinated, I was in an off-post Laundromat. I had been Charge of Quarters (CQ) in the stable the night before and had the day off, and was doing my laundry. When I was walking back to our barracks, I passed some people clustered around a car, listening to the radio. That is when I learned of the assassination. I was stunned.

At the time I was a 19 year old Private First Class in The Old Guard at Fort Myer, Virginia and had been walking the caparisoned horse (usually Black Jack, sometimes Shorty) in funerals in Arlington National Cemetery (ANC) for about nine months. The caparisoned horse in a military funeral procession is an ancient tradition, symbolizing a fallen leader who will ride no more. A caparison is “an ornamental covering for a horse or for its saddle or harness.” A caparisoned horse with walker will follow a caisson in a funeral at ANC if the deceased was an Army or Marine Corps colonel or above, or had ever served in a mounted outfit. The horse’s tack consists of bridle, saddle and blanket, boots and saber. The boots are turned backward in the stirrups to symbolize the fallen leader looking back over his past life.

I led the Caparisoned Horse throughout the State Funeral for President John F. Kennedy in November 1963. Black Jack (named for General “Black Jack” Pershing) was the last horse with an Army serial number. He had come from the Remount Station at Fort Reno and had 2CV-56 branded on the left side of his neck, and US branded on his left flank. He had very small hooves, and no one was allowed to ride him.

Chief Warrant Officer John McKinney, the leader of the Caisson Platoon picked the White Horse Section for the caisson, and named Black Jack and me for the JFK funeral. My usual replacement would ride Swing with the caisson. Black Jack was taller than Shorty, with an even temperament. Shorty was an evil kicker who did not deal well with loud noises. Last year I got a phone call fiom the first man who walked Black Jack in funerals. He said that Black Jack was wild when he arrived at Caisson Platoon. It took six months to settle him enough to use him in funerals, and he still would dance a lot. We knew nothing about this.

My first part in the Funeral was to follow the caisson as it carried the casket from the White House to the Capitol Building, to lie in state. To reach the White House, Black Jack and I followed the caisson from the stable at Fort Myer, through Arlington National Cemetery, across Memorial Bridge, to the courtyard inside the Treasury Building. We waited there for a time, resting and checking everything again. I think it was then we heard that Lee Harvey Oswald had been killed, and wondered what was happening to our country.

Black Jack was calm. It was the proverbial calm before the storm. When told to move out we exited through a narrow street-level tunnel, barely large enough for the horses and caisson. A large steel grate was leaning against a wall inside the tunnel, and the hub of the right rear wheel of the caisson hooked it and started dragging it along the cobblestone paving and the stone wall. The noise inside the tunnel was huge, and Black Jack went wild. He stayed agitated for the next three days, for the entire Funeral.

Our usual position was behind the caisson, and facing it. At the White House, instead of standing steady, Black Jack constantly threw his head and danced around me. After about 10 seconds people stopped crowding us and gave us space. We carried the president’s body from the White House to the Capitol. Then we moved out and walked back to the stable. When we got there, the few men who had stayed to take care of the other horses said that all the TV people had talked constantly about Black Jack and the soldier with him. The horse had the public’s attention.

We took care of the horses and tack, and then watched tapes of the first day on the TV set in the CQ room. It was a chance to critique everything we had done, look for opportunities for improvement. We hoped that Black Jack would settle down before the next part of the funeral.

After the president had lain in state, we went back to the Capitol. Black Jack continued to act up. We moved the president’s body to Saint Matthew’s Cathedral for the fimeral service. I saw Charles DeGaulle and Haile Salassie, men who influenced history, among the mourners, and also Mrs. Kennedy and Prince Phillip of England. I have never seen a crowd so still and silent. We heard later that when Prince Phillip was designated to represent England, he was told there was no need to hurry - it would take at least 2 weeks to plan and execute such a funeral.

The route was lined with soldiers on both sides standing at parade rest. As the caisson neared they would come to attention. I felt sorry for men having to stand so still for so long. One man who had that duty said that he felt something in his hand behind his back, and a woman whispered “It’s a sugar cube. Put it in your mouth and suck it when you get the chance.’’ From the corner of his eye he saw a female major going to each soldier.

At the cathedral people again decided not to crowd Black Jack and me. I tried to stand at parade rest holding his bridle - at least one of us should behave in proper military fashion. At one point he was pawing the pavement and struck my right shoe. I was afraid some toes might be broken. Later I found that the shoe was ruined, but no bones were broken. The shoe had to be replaced.

Police officers were doing crowd control. Two of them were quietly chatting up a couple of young women, and then their lieutenant came over and spoke to them in a deadly whisper, and they were silent.

After the fimeral service, we headed toward Arlington National Cemetery. Black Jack continued to dance and throw his head strongly. I was getting desperately tired, especially my right arm, but knew that if that horse got away from me I would be walking guard around a radar station in Greenland before the week was out.

At one point bagpipes played. I had trouble getting the beat, but once I learned to march with the music it gave me a burst of energy. That is music to fight by. Then the pipes went silent, and the energy burst faded. By Memorial Bridge I was so tired I had to make a choice - good posture or keep step with the drumbeat. I chose keeping in step.

At the gravesite, Black Jack and I would normally move to the front wheel of the caisson opposite the grave, and face the casket as it was carried fi-om caisson to grave. This time we could not do that because the crowd was so thick, and Black Jack was back on home territory and too tired to make room for us.

As we stood behind the caisson the Air Force did a Missing Man flyover, and then Air Force One flew over alone. It was almost over, and I allowed myself to choke up. Then the firing party fired three volleys and Taps was played. The bugler broke on one note of Taps - we assumed he got choked up, too.

We pushed our way through the crowd, and went back through the cemetery to our stable. We took care of our horses and tack, and it was almost over. We got a phone call that Mrs. Kennedy wanted the tack from Black Jack. I put on a fresh uniform and borrowed some shoes, and took all of his tack - cleaned but not polished - to the White House and gave it to a colonel.

A cardinal rule of broadcasting is No Dead Air. On-air personalities are required to talk constantly. Nothing so attracts attention as misbehavior, and that is why Black Jack and the man walking him became famous. In a pre-funeral meeting someone brought up that horses are bad to poop in public - very unsightly, and asked if not feeding them for a day would prevent that. Mr. McKinney asked what the result would be if they did not feed the soldiers for a day before the funeral. He was told that the soldiers would probably pass out. “That is what the horses will do, too.” End of discussion.

My daughter grew up knowing what Dear Old Dad had done back in pre-history, before she was born, and attached little importance to it. Then when she was in college I got an excited phone call: “Dad, did you know you are in a Michael Jackson video? Man in the Mirror! You are in it!” So now Dear Old Dad became important at last.

Arthur A. Carlson January 2008

[...]

[...]

FOUR DARK DAYS IN NOVEMBER By Douglas A. Mayfield

In November 1963 I was a 21-year-old Army Specialist 4th Class assigned to the Honor Guard Company of the Old Guard, stationed at Ft. Myer, Virginia. I had been with the Honor Guard Company since June 1962 and was a member of the second platoon, burial detail. Although I participated in many types of ceremonies, my primary duty was that of a pallbearer for funeral services in Arlington National Cemetery. On Friday, November 22, 1963 in the early afternoon hours, my team and I had just finished the last h e r a l service of the day and boarded the transport bus to take us back to Honor Guard Company. As I was about to sit down I noticed the bugler sitting in the back of the bus holding a small transistor radio. With a solemn expression on his face I remember he blurted out “The President has been shot!”

My first reaction was obvious shock and disbelief. There wasn’t any information on the circumstances, or his condition, only that he had been shot in Dallas, Texas. On returning to Honor Guard Company, LT Sam Bird, 2nd Platoon Leader, was already waiting in the Znd Platoon barracks. As we entered the barracks he informed us the president had in fact expired. He also told us that Sgt. James Felder, the NCOIC (Non Commission Officer In Charge) of the 2nd Platoon in charge of “A” squad burial team (also known as “regulars”), had phoned the Honor Guard Company from his vacationing location and was en route back to Ft. Myer. After Sgt. Felder arrived, LT Bird selected and assembled two teams of pallbearers &om the 2nd Platoon to be transported to Andrews Air Force Base to await the arrival of Air Force One (President’s personal jet).

The two teams flew from Fort Myer to Andrews AFB on two H-21 helicopters, arriving 30 minutes before Air Force One landed. At Andrews Air Force Base, Honor Guard members from other military branches were assembled with the Army Honor Guard unit, forming two complete joint military six-man teams. LT Bird selected Sgt. Felder and myself to be on the primary team that would eventually carry the president throughout the rest of the funeral procession and ceremonies. This selection was possibly due to Sgt. Felder and myself having both been the two senior noncoms of 2nd platoon. In addition to having seniority and experience, we had also worked together on the same team on hundreds of funerals.

As Air Force One landed and the baggage doors opened, the plan was to have one team on the baggage lift truck who would pass the casket down to the primary team waiting on the ground. This plan never materialized due to the Secret Service insisting they would be carrying the casket and we were to step back out of the way.

I remember LT Bird complying with this order and had Sgt. Felder march us approximately ten paces from the back of the waiting ambulance. We stopped, did an about face and were prepared to watch the secret service place the casket in the ambulance. Watching the poor handling of the casket I’m sure LT Bird was seething, as it didn’t take long before he ordered Sgt. Felder, Marine L/Cpl Tim Cheek and Air Force Sgt. Richard Gaudrea to step to the back of the ambulance and physically assist the Secret Service. The Secret Service obviously objected to this assistance due to what I observed to be light jostling between the Secret Service and the military.

Once the casket was secured in the ambulance, LT Bird had the primary team board an army helicopter and fly to Bethesda Hospital. At the hospital we carried the casket from the ambulance to a small room that led to the autopsy room. There we performed security duties by standing guard outside the small room.

Marine L/Cpl Cheek and myself took the first watch and were standing at parade rest when I saw a camera flash come from a small window in the door at the end of the hallway. Somehow a news media photographer was able to sneak past most secured entries and snap one photograph before being confronted and removed from the premises. Shortly thereafter I saw the hands of someone on the other side of the door taping paper across the small window. That one and only photograph taken inside the hospital by an unknown photographer was later seen printed on page 32B of the November 29, 1963 issue of Life Magazine.

LT Bird then approached us and told us to relax from parade rest, as we would be there for the next several hours. He also told us that he was informed that Marine sentries were placed at every entrance to the hospital to prevent any other unauthorized personnel or photographers from entering the building. [NOTE: A somewhat different description of the confbsion at Andrews AFB and at Bethesda Naval Hospital appears in the account of Richard Cross, who was not present at either site, at Tab 1, Page 2. Editors]

At Bethesda Naval Hospital, an autopsy was performed, the President’s body was embalmed, and it was placed in a new mahogany casket to replace the one that had been damaged while it was being unloaded at Andrews AFB. The procedures took many hours to complete.

The replacement casket was considerably heavier than the original one.

The following morning, Saturday, November 23rd at approximately 4:00am, we placed the casket with the president’s body into the ambulance that transported the president fiom Air Force One to Bethesda Hospital. The ambulance was directed to the front entrance of the White House as we followed behind in a limousine. Prior to reaching the front entrance we exited the limousine and marched behind the ambulance. I remember as we approached the entrance flash bulbs and bright lights suddenly illuminated the area like daylight.

As we removed the casket from the ambulance and started for the entrance to the White House it was obvious that the weight of the casket bearing the President was beyond all of our expectations. I had carried hundreds of caskets during funerals at Arlington Cemetery and none came even close to the weight we were bearing. If media records were correct the casket reportedly weighed over 1,300 pounds. This meant the average weight for each six pallbearers exceeded 200 pounds.

With each step I felt the casket slowly start to descend. Ignoring the lights and media I attempted to gain LT Bird’s attention by whispering his rank without turning my head towards him. He was approximately two to three paces behind us. After a couple of unsuccesshl attempts I finally turned toward him and softly blurted out “Lieutenant!” He quickly stepped forward and grabbed the end of the casket.

This was the only verbal remark made while entering the White House by me or any other team member, contrary to a published book that erroneously claimed that I whispered imploringly “Good God, don’t let go!”

After the casket was placed on the catafalque in the East Wing of the White House, we left and had a quick briefing with LT Bird regarding the weight of the casket and the concern of the impending steps of the Capitol. The overall consensus of the entire team agreed that additional pallbearers were needed before trying to ascend up the Capitol steps. LT Bird agreed and assured us he would see that two more pallbearers be added. LT Bird succeeded and Seaman Larry Smith of the Navy and PFC Jerry Diamond of the Marine Corps were welcomed additions as the seventh and eighth members of the team.

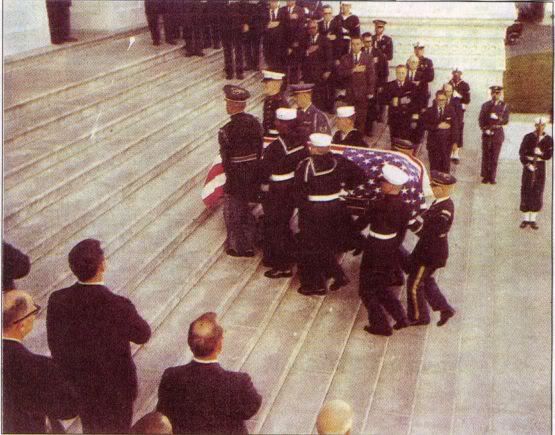

On Sunday, November 24&, in the early afternoon hours we removed the casket from the East Room of the White House and placed it on the waiting caisson. From there we marched behind the caisson during the procession to the Capitol. I remember I was in awe of the number of people lining the streets. They appeared ten to fifteen persons deep and stretched the entire route from the White House to the Capitol. As we arrived at the base of the Capitol steps I remember looking at the steep incline and thinking it looked more like a wall than steps.

I had been up and down the steps many times before but never while carrying a heavy load. I couldn’t stop thinking that even if we made it to the top without a flaw that we still had to look forward to coming down the following day, which was even more frightening. I was greatly relieved when we reached the top and placed the casket on the catafalque in the rotunda.

Afterwards, we returned to Fort Myer, where the rest of the day was spent preparing uniforms, shining shoes, and practicing for hours holding and folding the flag. As good as each member was individually, it was critical that we practice together over and over again since two days before we had never met and didn’t know each other. As simple as folding a flag appears, if just one member falters or the team’s timing is off the flag could be dropped, red and white stripes could be other than straight, and red could be showing in the triangular folded flag where only blue with white stars are supposed to be. We knew that we would be watched and scrutinized by millions of viewers and we wanted to give the impression that we had conducted hundreds of fimerals together and operating in unison was second nature to us.

I remember late Sunday evening around midnight the team was transported fiom the Army Honor Guard Company to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. LT Bird knew that carrying the casket down the Capitol steps would be the most difficult part of the funeral and the team needed to practice descending down steps away from the public’s eye. The tomb was perfect since it had similar steps like the Capitol and the cemetery was closed at night.

LT Bird made arrangements for a practice casket to be delivered from the Army Honor Guard Casket Burial Platoon to use as a prop. Practice caskets are very light and used to train new members to the Casket Burial Platoon. I was familiar with this casket and noticed it appeared heavier than normal. It was believed that somewhere between Army Honor Guard Company and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, sandbags were placed inside for realism extra weight. Even with the added sandbags, the casket was still no comparison to the actual weight of the president’s casket. LT Bird then had two members of the Tomb Guard of the Unknown Soldier, who were not working at the time, climb on top of the casket and the team carried the casket up and down the tomb steps for approximately one hour. Even with the sandbags and tomb guards, it was still nowhere near the weight it needed to be in order to compare it with the president’s casket.

On Monday morning, November 25*, the team was transported to the Capitol by an army bus to retrieve the president’s casket from the catafalque. I remember we were approximately a quarter mile from the Capitol when the number of mourners became so heavy that the bus driver was having difficulty maneuvering the bus through the crowd. After a couple of times of honking his horn with no luck, L.T Bird had us disembark and march the rest of the way to the Capitol.

Once inside the rotunda, we lifted the casket from the catafalque and started towards the top of the steps. It was then when I became very nervous. This was the biggest challenge so far and my thoughts were not only the fear of going down the steps but having to stop at the top before descending and hold the heavy casket while the band played two or three different hymns.

Luckily Lt. Bird was able to have Sgt. Jesse Sharp from the Army Honor Guard, 2nd Platoon waiting at the top of the steps to assist. When the band started to play, Sgt. Sharp stepped forward fiom behind a pillar and with his back to the casket held one end while LT Bird held the other. I remember they took the brunt of the weight allowing the rest of us to discretely relax one hand then alternate to the other while the music played. [NOTE: In his account at Tab 20 Sharp does not mention giving the casket team a short respite by bearing part of the weight for a few moments. Sharp says his only role while at the top of the steps was as a spotter to signal when the Kennedy family had reached the bottom of the steps.-Editors]

Once we started down the steps my only thought was we had to move in unison or the danger of one person tripping another would be a complete disaster. Once we reached the bottom of the steps and placed the casket on the caisson, we again could give a sigh of relief. The only steps left were those in front of St. Matthews Cathedral and they were no comparison to what we just endured.

At St. Matthew's Cathedral, the team carried the casket up the few steps and just inside the entrance doors we placed the casket on a church truck with wheels. [NOTE: Mayfield does not remember an incident on the steps when Cardinal Cushing stopped the casket to bless it, leaving the casket bearers in a difficult and awkward position, as reported by LTC Cross at Tab 5 and also by CPT Mc Namara at Tab 12-Editors]

Sgt. Felder and I then escorted the casket to the front portion of the church where Cardinal Cushing, the Archbishop of Boston, was waiting to conduct Mass. Once Mass was completed, Sgt. Felder and I returned to the casket and turned the church truck around to escort it to the rest of the waiting team at the front entrance to the church. It was necessary to turn the casket around since protocol requires the casket to always face feet first when the casket is carried. From there we carried it down the few steps and placed it on the caisson for its final procession to Arlington National Cemetery.

The march from the cathedral to the cemetery was the longest march of the funeral. Estimated at three to four miles long, mourners lined the route from the church to the Arlington Cemetery gates. I remember I thought I had seen it all with the thousands of mourners at the Capitol, however that was nothing compared to this. It was also an eerie sensation that except for a few shouts of encouragement from the crowd, there was absolutely no noise except for the deafening sound of drums. I was haunted by the sound of drums for days after the funeral.

At Arlington Cemetery we removed the casket from the caisson and started slowly up a slight but long incline towards the gravesite. What made it difficult was the leading cortege was walking extremely slow in front of the casket. I remember Sgt. Felder softly asked them to walk faster. When this didn’t work I remember Sgt. Felder lightly bumped a priest with the casket. At the gravesite it was necessary to reverse direction so the head of the casket would be at the top of the gravesite facing Washington D.C. and the Potomac River.

Reversing the casket placed Marine Pfc. Jerry Diamond and myself to be the first to step on to the sideboards of the grave. I almost panicked when I noticed there were no support boards across the grave. I thought perhaps the persons responsible for the gravesite forgot the support boards. The only items present to support the casket were two wide straps stretched across the grave.

In the hundreds of funerals I performed at Arlington Cemetery there were always support boards in addition to lowering straps. I had never seen a grave with only straps. I was so afraid we would set the casket down on just the two straps and the casket would literally drop out of sight. I remember trying to alert LT Bird or Sgt. Felder when I heard someone say everything was fine and the straps would hold the weight. Regardless I held my breath when we set the casket down. The rest of the funeral went smoothly and I knew we as a team had successfully achieved what we were trained to do.

A few days later I remember LT Bird inviting the team to his officer’s quarters to discuss and critique the entire event. What I didn’t know was that sometime during the funeral while assisting the team in carrying the casket, LT Bird observed a label on the draped flag. The label identified the manufacturer of the flag and LT Bird, being the person he was, contacted the company to let them know it was their flag that was part of the most famous funeral in American history. The company was so appreciative they sent each member of the team a solid brass desk flag engraved with our individual name, rank and title of “Casket Team” to commemorate the event.

LT Bird also presented to each member of the team a copy of a tape he recorded the evening after the funeral. LT Bird informed us that after the funeral he returned to his officer’s quarters to take a well-deserved rest. However, when he sat down he turned on the TV and observed the funeral being displayed from its entirety. With this he turned on his tape recorder and began to narrate the entire funeral. This lasted until midnight when the TV station ended its broadcast and went off the air. The Kennedy family somehow learned of LT Bird’s endeavor and requested a copy of the tape. A copy of the tape now reportedly resides in the Kennedy library in Boston, Massachusetts. LT Bird also provided each member of the team several 8x10 black and white photographs of the entire funeral. I still have the desk flag, tape and photographs and cherish them as much as I cherish the honor of being one of the members of this particular Joint Military Pallbearers team.

By Douglas A. Mayfield April 2008

[...] [...]

FOUR DAYS IN NOVEMBER 1963 By Thomas F. Reid

I learned of the death of President John F. Kennedy by watching TV in The Old Guard Regimental Headquarters. The word the president had been shot in Dallas spread quickly by word-of-mouth. I went to Regimental Headquarters, and was there when I saw Walter Cronkite take off his dark rimmed glasses to announce the fatal news. It seemed like a bad dream, impossible, but true. On November 22, 1963 I was a 26-year-old Captain, the Company Commander of D. Company of the 3rd US Infantry, (The Old Guard).

According to the master plan for State Funerals, the person occupying my position was designated to be responsible for the Interment Ceremony in Arlington National Cemetery (ANC). There was initial speculation that the president might be buried in the family plot in Brookline, Mass. When the president’s family accepted the offer made by the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara of the gravesite in ANC, I went into action as the Ceremonial Site Control Officer, planning and preparing for the Interment Ceremony.

The Military District of Washington (MDW) had a master plan for conducting a State Funeral. There was a specific individual plan tailored for each person entitled to receive a State Funeral, such as Former Presidents Hoover, Truman, Eisenhower and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Each quarter we would have a Command Post Exercise (CPX) to rehearse one of these specific plans. But, we never rehearsed the funeral of the incumbent president, so no specific plan had been formulated for him. We only had the basic master plan to work with as a template.

For my command post I set up a temporary office in vacant space located in the basement of the white marble ANC Amphitheater, opposite the underground quarters for the Guard of the Tomb of the Unknowns. I chose as my deputy one of my platoon leaders, First LT Wesley Groesbeck. The NCO who manned the CP was the company Training NCO, SSG E-6 John R. McLaughlin. He had a desk, a telephone and a cot installed. I did not get to sleep on it very much. D Company operated for the rest of the tumultuous week under the leadership of the Executive Officer, First LT Edward Gripkey, and First Sergeant Melvin Richardson. Ed Gripkey was the Acting Company Commander for the duration of the State Funeral. I was fully immersed in my duties as Site Control Officer, and was completely separated from my company during the four-day funeral.

The State Funeral lasted four days, culminating with the burial in ANC on November 25, 1963. Every evening there was a briefing at MDW Headquarters, where key personnel would receive a report of that day’s activities, plans for the next day, and comments from the president’s family. Every day new elements were added to the Interment Plan, and I had to devise some way to carry them out. First, it was announced that the family wanted an eternal flame, modeled on the one at the Grave of the Unknown Soldier of France, at the Arc de Triomphe. I wondered, what, exactly is an eternal flame, and where do you go to get one? It was fabricated overnight by Army engineers at Fort Belvoir.

Then, since the president had done much to popularize the Arrny Special Forces, a planeload of Green Berets was flown in from Fort Bragg, and I had to find a position of prominence for them in the cemetery ceremony. This was done by forming them into an honor cordon between the caisson and the grave. The Special Forces had a reputation as being rough and tough, but they were not accustomed to ceremonial duty. When one of them in the cordon “took a knee” after standing in position for a long time, the ceremonial troops who saw him go down smiled as if they were amused at his misfortune.

Next, the Air Force Bagpipe Band was given a role in the ceremony, and I had to find a way to fit them into the sequence of events. At the last minute, I was told by MDW to expect the arrival of a nine-man detachment from the British Black Watch Regiment, and to fit them into the ceremony someplace. Finally, a drill team of Irish Guards from the Irish Military Academy was supposed to perform a special routine that they had performed for the President and Mrs. Kennedy when they visited Ireland. The Interment Ceremony was quickly becoming a three-ring circus. It was already up to two rings, and climbing.

The master funeral plan that we began with was rapidly becoming unrecognizable and irrelevant. Something was changed, or added to it several times a day. Improvisation became critical. The Secret Service was not available when we made the initial reconnaissance of the designated gravesite. We roughly laid out the location of the key elements of the ceremony, including the security cordon enclosing the entire site. Later, when the Secret Service was able to examine the ceremony site, they greatly enlarged the size of the security cordon. However, by then all ceremonial troops were Eully committed to other tasks, and none were available for this purpose.

An emergency call went out to Fort Belvoir, and the 91st Combat Engineer Battalion, under the command of LTC Clark was pressed into service on short notice, with very little time to prepare for a task they were not trained to perform. They showed up wearing green uniforms, because combat engineers are not issued dress blues. Without having a chance to train for such an unusual mission, or time to prepare adequately, they did a very good job under difficult circumstances, and lived up to the Corps of Engineers’ motto, ESSAYONS, Let us try.

The Secret Service was extremely nervous about security precautions. They had just lost the president they were sworn to protect, and there was no backup readily available for Lyndon Johnson, who had assumed the office. The Secret Service accepted nothing at face value. They worried that the eternal flame would explode when Mrs. Kennedy tried to light it. In an abundance of caution, an agent climbed into the grave before the ceremony to look under the green mats of false grass (Astroturf had not yet been invented), which hung down over the sides of the grave to conceal the freshly dug earth. I suppose he was making sure there were no surprises underneath that could go Boom. I had to give him a hand to help him climb back out when he had finished his close examination of the grave.

There were heaps of flowers delivered to the gravesite before the ceremony. A huge bank of flowers was arrayed near the grave. On the morning of the ceremony, Leticia Baldrige, who was Jackie Kennedy’s Social Secretary and Chief of Staff, arrived at the grave carrying a wicker basket of flowers that was Mrs. Kennedy’s personal floral tribute. A Secret Service Agent who was there, watched her approach, and asked me who she was. I told him. He said that he was not normally on the White House detail, and he did not know her by sight. He asked if I could identify her. I said, “No, but I had been told to expect her.” The agent went over to her, and carefully looked through the flowers in her basket to make sure there was nothing amiss. They were taking no chances that day.

Earlier, a Secret Service Agent pointed to the newly installed burner for the eternal flame, and asked me what it was. I told him. He asked me what would happen with it. I told him that Mrs. Kennedy would light it with a taper. The burner stood almost knee-high, and had pine boughs piled up around it to improve its appearance. The agent objected to the plan, saying that the gas fuel would accumulate and blow up when she lit it. I explained that this was Mrs. Kennedy’s personal request and a Lieutenant Colonel, the Fort Myer Post Engineer would be standing behind a nearby bush with a propane tank, and he would not turn on the gas to the burner until Mrs. Kennedy moved toward it. He still objected, saying that she might miss the burner, and accidentally ignite the pine boughs, which would cause it to blow up. To minimize this risk, two buckets of water would be poured on the branches before the ceremony. He reluctantly agreed, but despite all our precautions, he had misgivings that it would still blow up. It did not explode.

I foolishly thought that, as Site Control Officer, I was in charge of organizing the ceremony in the cemetery. That notion was dispelled when I learned of the power of the press the hard way. TV coverage of the ceremony was provided by NBC, which provided pool coverage for all three networks. CNN had not yet been invented.

As we were busy laying out can tops to mark the positions of key personnel, a man who introduced himself as Bill Jones, of NBC, approached me. He inquired where the bugler and the firing party would be located. I pointed out their position. Bill Jones replied that our arrangement was unacceptable, because he would not be able to get the bugler on camera. He wanted the bugler to be located slightly down hill and directly in front of the firing party, who would fire the traditional three volleys of musketry right over his head immediately before he played Taps. I objected to the NBC layout, because the muzzle blast would impair the bugler’s ability to play Taps. Mr. Jones said it had to be done his way. He pointed out that previously, for the funeral of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, he had ordered the grave to be turned 30 degrees, so it would appear on camera.

He suggested that I call my Colonel to find out who was going to position the bugler, him or me. I phoned Lieutenant Colonel Richard Cross, Commanding Officer of The Old Guard, to report the problem. He was expecting my call, and he instructed me that Bill Jones, not I, would prevail. I just thought I was in charge. Lesson number one in learning the Power of the Press. The result was that the bugler cracked the sixth note when he played Taps. When that happened, somehow I felt vindicated. I wanted to grab Mi. Jones and tell him, “See, I told you it was a bad idea.!”

A different Armed Service Band played at each ceremonial site. The Navy Band played at the Capitol. The Marine Corps Band played at the ANC Interment Ceremony. After Taps was sounded, and while the flag was being folded, the USMC Band was supposed to play the Navy Hymn. The cue to begin was delivered with a head nod. This was practiced during rehearsal. Nonetheless, it took several vigorous gestures to get the bandleader’s wandering attention. In my after action report I was critical of the band’s performance. I recommended that in the future, the US Army Band should play at the Interment Ceremony in ANC.

The plan for the interment ceremony called for a formation of planes from the USAF to fly over the grave immediately after the casket was placed on the lowering device. On the morning of the interment, during final preparations, an Air Force fbll Colonel driving a tactical and non-ceremonial appearing jeep crammed with radios, showed up and told me he was the forward air controller who would call in the planes for the fly-over. The planes would be orbiting over Richmond, and it would take them 90 seconds to arrive after he called for them. He needed a signal fiom me exactly 90 seconds before the casket was placed on the lowering device. I had never timed any of the ceremonial activities, and had no idea when this 90-second mark would be. My best guess would have to do. I estimated that it would take the joint casket bearing team about 90 seconds to remove the casket fiom the caisson, carry it to the grave, and place it on the lowering device. I told the Colonel to conceal his scruffy looking vehicle out of the way. His signal would be the moment the casket bearers grasped the handle of the casket to remove it from the caisson. It turned out that I misjudged the time. The planes appeared overhead 10 seconds early, but nobody knew the difference except an Air Force Colonel driving a dirty jeep full of radios, and me.

My account is not chronological, largely because during these four days I lost all track of time, and even days. Events all blur together, and I am not sure when certain events took place. One event I am sure of, because it remains vivid in my mind, is being told by MDW to send somebody to the White House on Sunday, the third day, to brief Major General Ted Clifton, the president’s military aide, concerning the details of the interment ceremony the next day. Because the plans kept changing, I had not yet published the Ceremonial Order for the Interment Ceremony, and nobody else knew all the details except me.

I went to the White House to brief MG Clifton myself. When I arrived at his office, the General was at the Capitol Building, where the casket was being placed in the Rotunda. This is the unique, defining feature of a State Funeral, lying in state in the Capitol Rotunda. General Clifton’s wife was in his office, watching the Rotunda ceremony on the TV set in his office. She motioned for me to go in, and we watched the ceremony together until it ended. She said her husband would be back in about 15 minutes, and we waited for him together.

She asked me if I was there to talk about the ceremony in ANC the next day, and I said I was. I explained that at first, we thought the president might be buried in Boston, but that since the decision was made for ANC, we were working hard day and night to put together a ceremony worthy of the occasion. She looked startled, and said, “Captain, you sound like you are complaining about burying the President of the United States.” I assured her that I was not complaining in any way, that it was an honor for me to serve in this capacity. I merely wanted to point out that we were making every effort to produce the finest and most fitting ceremony possible. Neither of us said anything further. She was visibly mourning heavily, which may have caused her to misunderstand my remark.

When the General arrived, his wife greeted him in the outer office, and spoke to him briefly. She gestured in my direction, and may have been telling him that the captain waiting in his office was complaining about burying the President of the United States. When General Clifton came in, he said nothing about my speaking to his wife. I conducted my briefing, and left. No mention was made of his wife. When I reached my CP in ANC, there was a message to phone the Commander of The Old Guard, LTC Richard Cross. I did so, and LTC Cross said something to the effect that “I do not understand what is going on, but MG Clifton does not want you to officiate at the Interment. We are putting Major Stanley Converse in charge, and I want you to brief him thoroughly, because he knows nothing about the ceremony.

I gave MAJ Converse the most intensive briefing he ever received, covering every minute detail of the ceremony.” I instructed my deputy, LT Groesbeck how to attend to the few loose ends remaining. LTC Cross did not inquire why MG Clifton might want me removed, and I do not remember telling anybody at the time about my conversation with his wife. We had scheduled a final skeleton rehearsal for key personnel at the gravesite early on the morning of the ceremony. MG Clifton attended the final rehearsal, which I conducted, because MAJ Converse was still learning the right moves to make.

Following the skeleton rehearsal, I returned to my orderly room to change into my dress blues to perform the interment ceremony. I received another phone call from LTC Cross, who said “I still do not understand what is going on, but for some reason, MG Clifton has ordered that you are not allowed in ANC during the interment ceremony. Do not go to the cemetery.” Stunned, I removed my blues and watched the ceremony I had worked so hard to put together, in a state of shock, on the TV in the company day room, with my orderly, SP-4 Langfitt. He must have wondered why I was not in the cemetery. So did I.

My Executive Officer, LT Gripkey went to the Cemetery with Lt. Groesbeck, my deputy, to provide a backup system to make sure that head nod signals were received by their intended recipients, by cueing MAJ Converse at the appropriate moment. The primary task remaining for MAJ Converse to perform was to help Jackie Kennedy light the eternal flame, making sure it did not blow up as the Secret Service feared. NOTE: LTC Cross has a different memory of whether he fired Reid. See Tab 5, Page 3 .-Editors]

I never received an explanation from either LTC Cross or MG Clifton. The only reason I can think of for being sacked fiom the most important job in my life, is one comment I made to a woman who was grieving heavily, and who misunderstood me. My participation in the JFK State Funeral ended prematurely and abruptly.

Now, at age 70, looking back at the events of 44 years ago, I am struck by the degree of responsibility that I had as a young, 26-year-old captain, by how much I had to improvise, and by the wide range of details I attended to. But, that is the way of the Army. It is young men and women, little more than babies, who we call on to fight and die in our wars, and there is no greater responsibility than that. It was an honor for me to have had a significant role in what may have been The Old Guard’s finest hour. Outside of actual combat, it was the most intense and demanding four days I ever experienced.

Epilogue When the last car in the motorcade left the cemetery after the interment, and the cemetery gates were closed for the night, we all breathed a sigh of relief. We had worked at a high level of intensity for four days. The Funeral required all of our resources, and tested us to the limit, but we had done it, and done it well. I thought our work was finished. It was not over. It was just beginning.

When the cemetery gates were opened the next morning, there were literally thousands of people milling around outside, waiting to visit the new grave. I do not know about others, but I did not see it coming. It immediately became apparent that crowd control measures were needed to maintain order at the gravesite. A number of different steps were taken. A detail of soldiers was dispatched to the gravesite to maintain order. Metal stanchions with cords stretched between them were erected to form lines for the people to wait in.

Visitors arrived at the grave at the rate of 3,000 per hour! Visitors were placing a variety of objects at the grave, and rules were quickly established concerning the types of objects that would be permitted. These objects were removed each night, and catalogued by the National Park Service. Special provisions were made for the numerous dignitaries who visited the grave, some of whom wanted to lay a wreath. Unexpected behaviors occurred, and rules were established regarding what activities would be allowed. Some people would pray aloud, sing hymns and perform various religious rituals. Some restrictions were needed. Heaps of flowers were left at the grave by visitors, which had to be removed daily by the truckload.

Within a very short time, a white picket fence was erected around the gravesite. A small Army school bus, normally used to transport troops fkom one military funeral to another in ANC, was parked near the gravesite to serve as a command post and to provide shelter for the troops. A telephone was installed. One Company of the Old Guard was designated daily to perform gravesite control duty. Many such temporary measures were taken, and others were developed over time. Eventually, a permanent gravesite was built, which incorporated the eternal flame. The original flame, which was fueled with propane initially, was later switched to natural gas. With the passage of time, the overwhelming public interest diminished somewhat, so less drastic measures were required.

Today, 44 years later, the Kennedy gravesite continues to attract more visitors than any other monument in Arlington National Cemetery, even than the Tomb of the Unknowns.

By Thomas F. Reid January 2008

Afterword

Even though I was summarily excluded fiom performing the Interment Ceremony, nevertheless, I was included in an awards ceremony held by The Old Guard and MDW at Fort Myer on February 13, 1964, at which Major General Philip C. Wehle, Commanding General of MDW presented medals to key figures in the Funeral. I received my first ARCOM-Army Commendation Medal. I thought it ironic to receive a medal for having been fired by a General's wife.

Captain Thomas F. Reid in 1963

I heard they played the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony during the procession on tv. I only scanned, did the article mention it?

By the way, before anyone else brings it up, I’ll settle the matter. Oswald killed him.

PING

Noli Me Tnageri

Will there ever be a day when we stop worshiping this guy as if he were a living god? Sheesh! He was a bad president. He served 3 years. He’s been dead almost 50 years. Who effing cares???

I was Old Guard 1962-63 discharged in Sep 1963 - just missed it.

Sept ‘63 is when I got there, we just missed each other.

Be glad you didn’t have to hump that casket up and down the capital steps.

omg i’ll never forget. i remember the look of shock on everyone’s faces but I”ll never forget my Da sitting in the kitchen crying and we were all crying as the television had brought up out of storage.

<><

I remember watching it on TV. Quite a few family members were at our place watching. My Grandfather snapped a few pictures of the tv screen with his brownie camera. I now have those photos (and the camera).

Excellent!

I dunno. Maybe he'll have to get in line behind Obambi now. I'm tired of the Kennedy worship as well. That said, I was a child in DC and my relatives took me to the funeral procession. I still remember Black Jack and the coffin.

I remember when all of my relatives had pictures of JFK, RFK, and Martin Luther King in their houses - next to the cross and a palm frond from Palm Sunday. I bet that many blacks have Obama 'shrines' in their homes now.

bookmark for later

That's what my mother used to advise me to tell any overly amorous boyfriends. LOL!

Excellent advice for daughters’ vocabulary as well.

;0)

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.