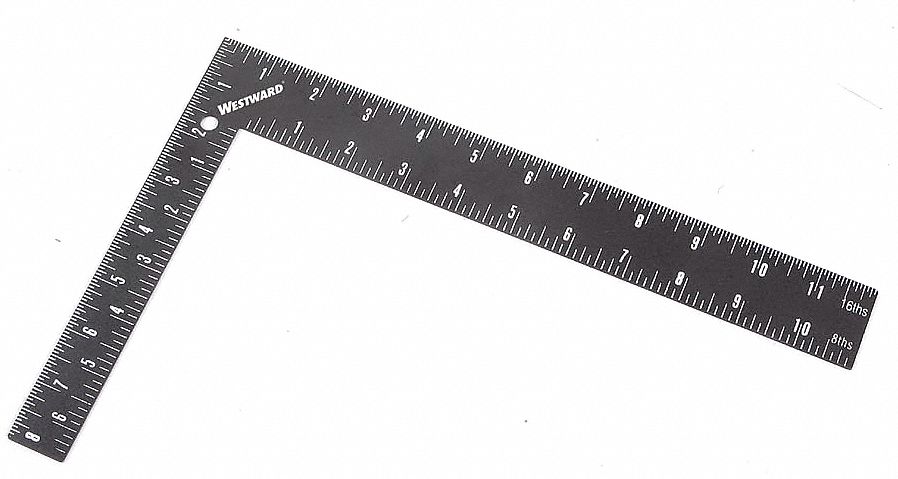

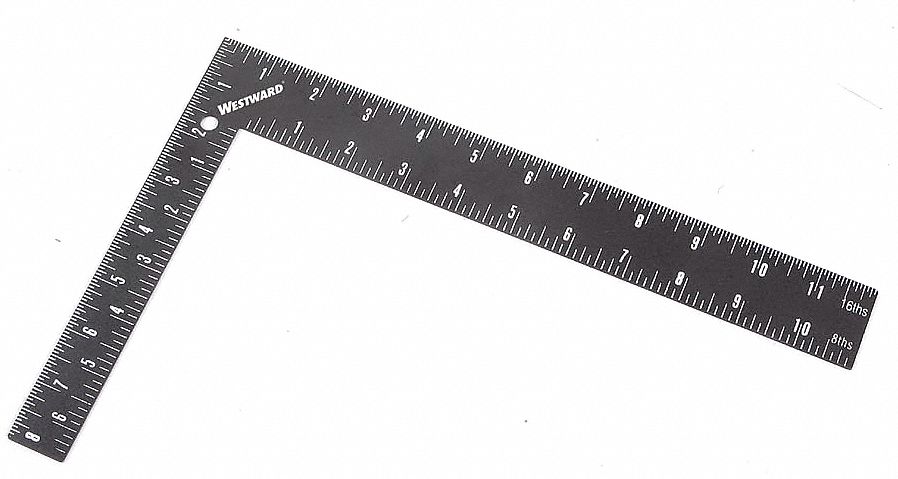

Carpenter's squares are analog computers. They are the carpenter's slide rules.

Posted on 09/27/2022 9:25:40 AM PDT by LibWhacker

Whenever "Gina," a fifth grader at a suburban public school on the East Coast, did her math homework, she never had to worry about whether she could get help from her mom.

"I help her a lot with homework," Gina's mother, a married, mid-level manager for a health care company, explained to us during an interview for a study we did about how teachers view students who complete their homework versus those who do not.

"I try to maybe re-explain things, like, things she might not understand," Gina's mom continued. "Like, if she's struggling, I try to teach her a different way. I understand that Gina is a very visual child but also needs to hear things, too. I know that when I'm reading it, and I'm writing it, and I'm saying it to her, she comprehends it better."

One of us is a sociologist who looks at how schools favor middle-class families. The other is a math education professor who examines how math teachers perceive their students based on their work.

We were curious about how teachers reward students who complete their homework and penalize and criticize those who don't—and whether there was any link between those things and family income.

By analyzing student report cards and interviewing teachers, students and parents, we found that teachers gave good grades for homework effort and other rewards to students from middle-class families like Gina, who happen to have college-educated parents who take an active role in helping their children complete their homework.

But when it comes to students such as "Jesse," who attends the same school as Gina and is the child of a poor, single mother of two, we found that teachers had a more bleak outlook.

The names "Jesse" and "Gina" are pseudonyms to protect the children's identities. Jesse can't count on his mom to help with his homework because she struggled in school herself.

"I had many difficulties in school," Jesse's mom told us for the same study. "I had behavior issues, attention-deficit. And so after seventh grade, they sent me to an alternative high school, which I thought was the worst thing in the world. We literally did, like, first and second grade work. So my education was horrible."

Jesse's mother admitted she still can't figure out division to this day.

"[My son will] ask me a question, and I'll go look at it and it's like algebra, in fifth grade. And I'm like: 'What's this?'" Jesse's mom said. "So it's really hard. Sometimes you just feel stupid. Because he's in fifth grade. And I'm like, I should be able to help my son with his homework in fifth grade."

Unlike Gina's parents, who are married and own their own home in a middle-class neighborhood, Jesse's mom isn't married and rents a place in a mobile home community. She had Jesse when she was a teenager and was raising Jesse and his brother mostly on her own, though with some help from her parents. Her son is eligible for free lunch.

An issue of equity

As a matter of fairness, we think teachers should take these kinds of economic and social disparities into account in how they teach and grade students. But what we found in the schools we observed is that they usually don't, and instead they seemed to accept inequality as destiny. Consider, for instance, what a fourth grade teacher—one of 22 teachers we interviewed and observed during the study—told us about students and homework.

"I feel like there's a pocket here—a lower income pocket," one teacher said. "And that trickles down to less support at home, homework not being done, stuff not being returned and signed. It should be almost 50-50 between home and school. If they don't have the support at home, there's only so far I can take them. If they're not going to go home and do their homework, there's just not much I can do."

While educators recognize the different levels of resources that students have at home, they continue to assign homework that is too difficult for students to complete independently, and reward students who complete the homework anyway.

Consider, for example, how one seventh grade teacher described his approach to homework: "I post the answers to the homework for every course online. The kids do the homework, and they're supposed to check it and figure out if they need extra help. The kids who do that, there is an amazing correlation between that and positive grades. The kids who don't do that are bombing.

"I need to drill that to parents that they need to check homework with their student, get it checked to see if it's right or wrong and then ask me questions. I don't want to use class time to go over homework."

The problem is that the benefits of homework are not uniformly distributed. Rather, research shows that students from high-income families make bigger achievement gains through homework than students from low-income families.

This relationship has been found in both U.S. and Dutch schools, and it suggests that homework may contribute to disparities in students' performance in school.

Tougher struggles

On top of uneven academic benefits, research also reveals that making sense of the math homework assigned in U.S schools is often more difficult for parents who have limited educational attainment, parents who feel anxious over mathematical content. It is also difficult for parents who learned math using different approaches than those currently taught in the U.S..

Meanwhile, students from more-privileged families are disproportionately more likely to have a parent or a tutor available after school to help with homework, as well as parents who encourage them to seek help from their teachers if they have questions. And they are also more likely to have parents who feel entitled to intervene at school on their behalf.

False ideas about merit

In the schools we observed, teachers interpreted homework inequalities through what social scientists call the myth of meritocracy. The myth suggests that all students in the U.S. have the same opportunities to succeed in school and that any differences in students' outcomes are the result of different levels of effort. Teachers in our study said things that are in line with this belief.

For instance, one third grade teacher told us: "We're dealing with some really struggling kids. There are parents that I've never even met. They don't come to conferences. There's been no communication whatsoever. … I'll write notes home or emails; they never respond. There are kids who never do their homework, and clearly the parents are OK with that.

"When you don't have that support from home, what can you do? They can't study by themselves. So if they don't have parents that are going to help them out with that, then that's tough on them, and it shows."

“One of us is a sociologist who looks at how schools favor middle-class families. The other is a math education professor who examines how math teachers perceive their students based on their work.”

I had to stop right there because I knew the rest of the article would turn my stomach and outrage me.

My classmates who didn’t do great had to go to summer school. I went a few summers for courses I knew would be easier because I wasn’t the best student. Do kids not do this these days?

This, my friends, contains the answer. Destroy the family, destroy society. I don't blame the teachers for only being able to do so much, and I don't blame the kids for their limitations, emotional and otherwise. This is a much bigger problem.

And that’s the problem!

No mention in the article of IQ or the “Bell Curve.”

The woketardian propaganda in the article makes it obvious why.

The people who govern our country are lawyers.

They spend three years of their lives learning how to be lawyers.

They learn how to convince a jury.

They learn how to convince a jury to accept what they want the jury to accept.

This teaches them how to have a majority of the voters accept what they want them to accept.

If you want to change this country, the first step is to change the law schools.

“The article works from the assumption that “fairness” is the most important outcome. “

Fairness is equality of outcome according to these Marxists.

And if you can’t achieve this by elevating the performance of the low IQ students to that of the higher IQ, then you must handicap the higher IQ students to bring them down to that of the lower ones.

“THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal

before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter

than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was

stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the

211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing

vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.”

Prophecy from Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron”. You can read more here.

https://archive.org/stream/HarrisonBergeron/Harrison%20Bergeron_djvu.txt

Bullcrap. Sending homework is a waste of time. Half the time the parent does it or the kids do each others.

Also, the teachers have them at least 8 hours a day, 40 hours a week. Now they want to send you home for an extra 2 or 3 hours of work. So the school wants to monopolize 10-11 hours of the kid’s day.

Totalitarian crap. Homeschool kids do way more and usually wrap up by noon or so daily. German schools close by 1 each day.

The chudzpah to have the kid all day long, and then say you cannot teach them if they don’t do more at night? If the kid was locked in a closet for their whole life except the 8 hours a day at school you should fully be able to educate them.

The teacher is supposed to teach little Jesse how to do division, NOT the mom. The teacher has 8 hours a day to accomplish that task. The teacher failed, so they say the parent didn’t do their job at night.

“One of the things I teach my kids about math, is that people who are GOOD at math are ALWAYS looking for ways to simplify, not ways to make things more complicated.”

I was pretty good in math in HS, got as far as Algebra II. Never did any of my other classes homework. Tried college, that didn’t work out, went to a 9 month school on how to be a programmer.

Never looked back. 30 years in an office, now I have been working from home (Software Developer) for over 10 years.

Oh the hours of fun I had not doing my homework...

This is so completely wrong-headed. Meritocracy is not just about "effort". The truth is that family/effort/income aside, some kids are just smarter than others, and will do better.

"Meritocracy" isn't about moral or vue judgments. It's about the bottom line - who is the best at doing something. That's it.

“I’ve known carpenters that used geometry without ever being taught geometry. And they didn’t know they were using it.”

After 2 classes of high school Geometry, I was totally lost and ready to drop out.

Fortunately, a good and kind neighbor had his own construction company, and he showed me how he and later I would use geometry everyday.

My Grandfather was a master carpenter, I spent a weekend with him learning about how geometry impacts/covers us each day.

One of my friend’s dad was the local chief of police, and his Dad took me out to do non dangerous riding/driving if you knew the basic rules of physics and geometry.

I hated algebra, and no one ever taught me how to use it in everyday life. I got one D in my life, and it was is in basic college algebra. All my other courses up to and through an MBA were A’s and B’s.

‘I would say he probably uses those high schools subjects every day...’

I can guarantee you I have not used Plane Geometry nor any of the lab sciences I studied in any real workplace...

We used Algebra and Calculus in the Business school of the colleges I attended, especially in Accounting and Finance.

Homework is suppose to be re-enforcing the lessons learned at school. And I am against most homework at the elementary school level. A bit of reading is one thing. Hours of home work needing parental help to complete says that something is wrong with the teacher.

Occasionally one of the kids will bring home a worksheet to do because, for one reason on another, they did not get it done in class. But that is rare here.

Carpenter's squares are analog computers. They are the carpenter's slide rules.

He would be the first to tell you that on his job he never used the algebra, geometry, chemistry, and biology he excelled at in high school.

The most interesting thing I ever read about boundaries was a look at kids with defined vs undefined play areas.

When the play areas were defined you had the kids playing all over the place with a few going over the fence.

In the undefined you had the majority playing in a very small area with a few leaving entirely.

Providing limits allowed the kids greater freedom to explore. Which is a contradiction until you realize that kids are small and vulnerable and they know it.

They want kids to discover the beauty of math or other learning without giving them any skills to start with.

They shove them out of the car without even knowing what a map or compass is and tell them to have fun. The kid stands there shivering beside the road and never learns a thing.

It’s pretty obvious you did not read the article - the article goes not even mention race.

Good grief.

In one of them, a kid is doing his math homework and his father is trying to help him.

The father is surprised to see a question asking to find the least common denominator.

"They still haven't found the least common denominator? They were looking for that when I was a kid!"

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.