Skip to comments.

Expanding Uncertainty about the Hubble Constant

Thunderbolts.info ^

| 02/09/2007

Posted on 02/11/2007 2:49:36 AM PST by Swordmaker

Attempts to measure the size, age, and “expansion” of the universe may be a good deal less precise than advertised. But the problem is much worse if the astronomers’ assumptions are incorrect.

An astronomer at Ohio State University, using a new method that is independent of the Hubble relation (which relates redshift to distance), has determined that the Hubble constant (the rate at which the universe is expanding) is 15% lower than the accepted value. His measurements have a margin of error of 6%.

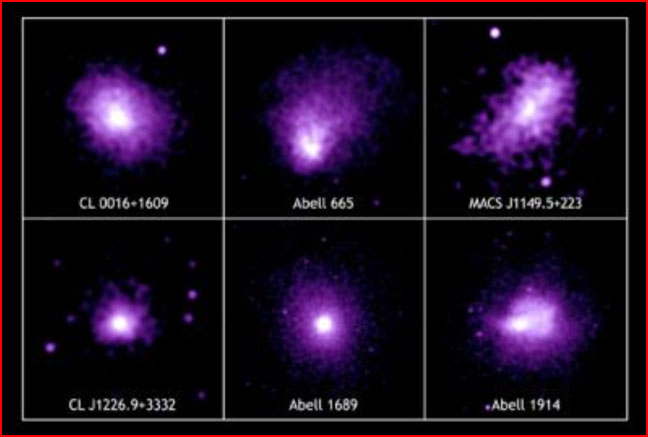

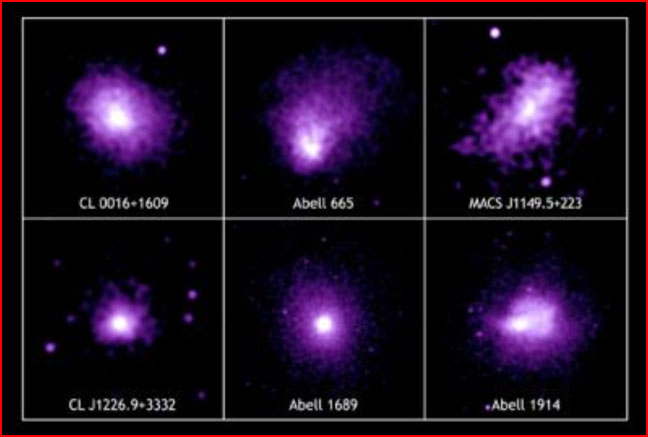

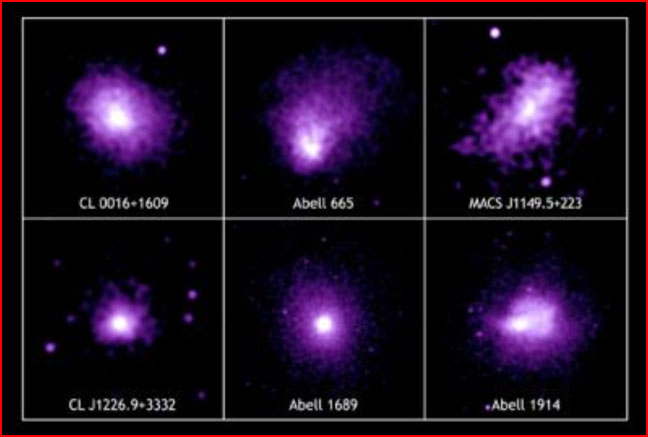

To “determine the Hubble constant” these six galaxy clusters are a subset of the 38 that scientists

observed with Chandra, their distances said to range from 1.4 to 9.3 million light years from Earth.

Credit: NASA/CXC/MSFC/M.Bonamente et al.

Meanwhile, NASA astronomers, using another new method that is independent of the Hubble relation, have determined that the Hubble constant is 7% higher than the accepted value. Their measurements have a margin of error of 15%.

Because traditional astronomers never question traditional assumptions (and appear not to recognize they even have any), they cannot be expected to mention that their margin of erroneous assumption is somewhere around 500%. That, of course, can account for their two “more precise” determinations in exactly opposite directions. They are in the same position as the clockmaker who attempts to determine the exact time of day by measuring the position of the minute hand and fails to notice that the hour hand is missing. Without recognizing that plasma makes up 99% of the universe and that it has dominant electrical properties, astronomers inhabit a make-believe universe in which precise measurements can mean precisely opposite things.

The first astronomer studied a bright eclipsing binary star system in the nearby spiral galaxy M33. He measured with state-of-the-art instruments the stars’ orbital period and apparent brightness. He calculated the stars’ masses, and then their absolute luminosities, and then their distance. His result was 3 million light-years instead of the 2.6 million that had been accepted.

One can presume that his measurements were accurate, at least to within 6%. But the assumptions that he took for granted were entirely erroneous:

- He assumed that gravity was the only force holding the stars in their orbits. Without this assumption, he would have been unable to calculate their masses. But in the past century, we discovered that the Law of Gravity loses its jurisdiction outside the Solar system: stellar jets and rings don’t obey it, globular clusters don’t obey it, galactic arms don’t obey it, galactic jets don’t obey it, galaxies in clusters don’t obey it. (To save their belief in the Law, astronomers had to imagine that the universe was composed mostly of invisible stuff—Dark Matter and Dark Energy.) A universe made of plasma will exhibit a variety of motions in addition to the “inverse square” force relationship that we call gravity.

- He assumed that the mass–luminosity relationship was constant for all galaxies. Astronomer Halton Arp’s observational work indicates that luminosity may decline with increasing redshift. A plasma universe powers stars electrically from external sources, so luminosity is not restricted to the mass-dependent output of thermonuclear fusion.

- He assumed that the “K effect” could be ignored. It’s been known since the early 1900s that the brightest stars (O and B spectral classes) have anomalous redshifts—if interpreted as a Doppler effect, they appear to be receding from Earth. In view of Arp’s finding mentioned above, bright stars may be less luminous than is assumed for their (gravity determined) mass, and hence calculations would overstate their distances.

NASA astronomers studied 38 compact galaxy clusters with the Chandra X-ray Telescope to “measure the precise X-ray properties of the [hot] gas” in them. They combined this with measurements from radio telescopes of the increase in energy of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation coming from the direction of the clusters. Then they used the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect, in which radiation gains energy from electrons in proportion to the electron density, temperature, and physical size of a region, to calculate the physical size of the clusters. After that, a simple trigonometry calculation gave them the distance. Dividing the redshift-determined speed of the cluster by the distance gave them the new Hubble constant.

"The reason this result is so significant is that we need the Hubble constant to tell us the size of the universe, its age, and how much matter it contains," said NASA's Max Bonamente, lead author of the paper describing the results. "Astronomers absolutely need to trust this number because we use it for countless calculations."

But again, the precise measurements were joined with precisely erroneous assumptions:

- They assumed that the x-rays were produced by hot gas. What they actually measured was x-ray intensities, and they applied standard gas laws to calculate how hot a gas had to be to radiate those x-rays. Plugging this figure into the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich equations resulted in a number for physical size. But a gas that hot will be ionized: It will be a plasma. It will have electromagnetic effects. In fact, a plasma can have electromagnetic effects—in this case, radiate x-rays—even if it’s not hot: fast electrons will spiral in a magnetic field and give off synchrotron radiation. Space plasmas routinely develop double layers that accelerate electrons (and positive ions) to high speeds. It shouldn’t be surprising that most x-ray radiation is synchrotron radiation.

- They assumed that the clusters were large, bright, and far away, and they were looking for some method to tell them how far. The observations of Halton Arp and others indicate that compact galactic clusters are small, faint “buckshot” ejections (rather than the “single shot” quasars) from nearby active galaxies. Like quasars, they are often paired across an active “parent” galaxy and may be enmeshed in radio-emitting and x-ray-emitting lobes of material coming from the parent galaxy.

- They assumed that the CMB is coming from the farthest reaches of the universe, passes through the cluster, and is energized. In a plasma universe, ubiquitous Birkeland currents will absorb and re-radiate microwaves: The CMB is a local effect, a kind of electromagnetic fog. Enhancement of CMB in front of clusters is simply an additive effect, not Sunyaev–Zel'dovich.

- They assumed that redshift was a Doppler effect, indicating velocity. Arp’s work (and others) demonstrates that galactic redshifts are mostly intrinsic: Galaxies with different redshifts are physically connected with bridges of luminous material, and the redshifts, when adjusted to the reference frame of the dominant galaxy, are periodic, occurring only at preferred values.

As Arp wrote in Seeing Red, "The greatest mistake in my opinion, and the one we continually make, is to let the theory guide the model. After a ridiculously long time it has finally dawned on me that establishment scientists actually proceed on the belief that theories tell you what is true and not true!"

Submitted by Mel Acheson

TOPICS: Astronomy; Science

KEYWORDS: astronomy; haltonarp; science; stringtheory

To: AndrewC; Fred Nerks; LeGrande; Miles the Slasher; SunkenCiv; Soaring Feather

A not so constant constant... PING!

If you want on or off the Electric Universe Ping List, Freepmail me.

2

posted on

02/11/2007 2:50:30 AM PST

by

Swordmaker

(Remember, the proper pronunciation of IE is "AAAAIIIIIEEEEEEE!)

To: Swordmaker

"[E]stablishment scientists actually proceed on the belief that theories tell you what is true and not true."

3

posted on

02/11/2007 2:57:06 AM PST

by

BenLurkin

To: Swordmaker

4

posted on

02/11/2007 3:06:34 AM PST

by

x_plus_one

(As long as we pretend to not be fighting Iran in Iraq, we can't pretend to win the war.)

To: Swordmaker

has determined that the Hubble constant (the rate at which the universe is expanding) is 15% lower than the accepted value. His measurements have a margin of error of 6%. And what was the previously advertised margin of error? Its all well and good to include assumptions in science, but giant red flags need to be attached when set before the general public.

5

posted on

02/11/2007 5:28:59 AM PST

by

SampleMan

(Islamic tolerance is practiced by killing you last.)

To: Swordmaker

It's worth keeping in mind that the red shift as an index of the expansion of the universe presumes that the velocity of light is constant, which measurements made over only the last 150 years don't provide enough data points to prove. While c is observably 'invariant', that's not quite the same thing as 'constant'.

6

posted on

02/11/2007 5:41:13 AM PST

by

Grut

To: Swordmaker

Because traditional astronomers never question traditional assumptions (and appear not to recognize they even have any), they cannot be expected to mention that their margin of erroneous assumption is somewhere around 500%. B.S. All real scientist are continuously aware of, and constantly question their assumptions. If scientist seem arrogant or cocksure occasionally, it is in response to critics who don't understand the assumptions or even realize that there are assumptions.

7

posted on

02/11/2007 5:59:53 AM PST

by

Lonesome in Massachussets

(When I search out the massed wheeling circles of the stars, my feet no longer touch the earth)

To: Swordmaker; RadioAstronomer

Because traditional astronomers never question traditional assumptions

Never is a long time to an Astronomer

8

posted on

02/11/2007 6:12:16 AM PST

by

grjr21

To: Grut

From

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variable_speed_of_light It is not clear what a variation in a dimensionful quantity actually means, since any such quantity can be changed merely by changing one's choice of units. John Barrow wrote:

"[An] important lesson we learn from the way that pure numbers like á define the world is what it really means for worlds to be different. The pure number we call the fine structure constant and denote by á is a combination of the electron charge, e, the speed of light, c, and Planck's constant, h. At first we might be tempted to think that a world in which the speed of light was slower would be a different world. But this would be a mistake. If c, h, and e were all changed so that the values they have in metric (or any other) units were different when we looked them up in our tables of physical constants, but the value of á remained the same, this new world would be observationally indistinguishable from our world. The only thing that counts in the definition of worlds are the values of the dimensionless constants of Nature. If all masses were doubled in value [ including the Planck mass mP ] you cannot tell because all the pure numbers defined by the ratios of any pair of masses are unchanged."[5]

==== End Wikipedia Extract =====

There available evidence seems to rule out any *observable* spacetime variability in fine structure constant. Any variability in the fine structure constant would seem to be much less than variations in the Hubble Constant, so a "varying speed of light" seems to be ruled out as an explanation.

9

posted on

02/11/2007 6:21:41 AM PST

by

Lonesome in Massachussets

(When I search out the massed wheeling circles of the stars, my feet no longer touch the earth)

To: RadioAstronomer; Swordmaker

To: Swordmaker

Space plasmas routinely develop double layers that accelerate electrons (and positive ions) to high speeds.

"It looks like...a FLUX CAPACITOR!" :-)

Full Disclosure: Meanwhile, down here on Earth, double layer theory at electrodes is kinda interesting :-)

11

posted on

02/11/2007 6:43:33 AM PST

by

grey_whiskers

(The opinions are solely those of the author and are subject to change without notice.)

To: Swordmaker

To: Grut

While c is observably 'invariant', that's not quite the same thing as 'constant'. The Speed of Light may be a local speed limit... we might be in a school zone...

13

posted on

02/11/2007 1:30:29 PM PST

by

Swordmaker

(Remember, the proper pronunciation of IE is "AAAAIIIIIEEEEEEE!)

To: Lonesome in Massachussets

It may be my lack of intelligence, but the wikipedia cite seems to me to be mostly gibberish, and tautological gibberish at that. My observation -- back in the 70s, incidentally -- was just that a decreasing value for

c would mean that older light would have its wave crests farther apart, i.e., show a red shift, so that we could have a universe of fixed size which

appeared to be expanding.

There are also some interesting secondary effects, such as much higher energy releases in distant/old processes because c^2 is much greater (quasars?) and a net loss of energy over time which might account for the time's arrow problem.

But I'm almost perfectly ignorant here.

14

posted on

02/11/2007 3:45:44 PM PST

by

Grut

15

posted on

02/11/2007 4:17:54 PM PST

by

SunkenCiv

(I last updated my profile on Saturday, February 3, 2007. https://secure.freerepublic.com/donate/)

To: Swordmaker

But again, the precise measurements were joined with precisely erroneous assumptions:

- They assumed ...

- They assumed ...

- They assumed ...

- They assumed ...

Bears repeating

16

posted on

02/11/2007 9:34:33 PM PST

by

AndrewC

(Duckpond, LLD, JSD (all honorary))

To: martin_fierro

Thanks for the ping. Gads - more Halton Arp. LOL!

17

posted on

02/12/2007 8:53:25 AM PST

by

RadioAstronomer

(Senior and Founding Member of Darwin Central)

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson