Nicole Etcheson, "Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era"

Posted on 11/21/2015 11:35:55 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

Before when free-soil men invoked the right of revolution in defense of their political rights, proslavery men condemned them for defying the legitimate government. But proslavery men feared the loss of their right to own slaves as much as free soilers feared the loss of the right to exclude slavery.

At Hickory Point, [Kansas] a squabble over land claims ignited these political quarrels. A settler named Franklin M. Coleman had been squatting on land abandoned by some Hoosiers, who subsequently sold the claim to Jacob Branson, another Hoosier. In late 1854, when Branson informed Coleman of his legal claim and attempted to move into Coleman’s house, Coleman held him off with a gun. A group of arbitrators later awarded part of the claim to Branson, but the boundaries between his land and Coleman’s were not determined. Branson invited in other men, including a young Ohioan named Charles W. Dow. Branson belonged to the free-state militia, a connection he used to intimidate Coleman, although Branson later testified that there had been no problems between Dow and Coleman – until the day of Dow’s murder.

On the morning of November 21, 1855, Dow went to the blacksmith shop at Hickory Point to have a wagon skein and lynchpin mended. While there he argued with one of Coleman’s friends, but left unharmed. As he walked away, he passed Coleman on the road. Coleman snapped a cap at him. When Dow turned around, he received a charge of buckshot in the chest and died immediately. His body lay in the road until Branson recovered it four hours later. Coleman claimed that Dow had threateningly raised the wagon skein (a two-foot piece of iron) as they argued over their claim dispute, forcing him to act in self-defense. Fearing that he could not get fair treatment at the free-state settlement of Hickory Point, Coleman and his family fled to Missouri.

Nicole Etcheson, “Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Eraâ€

I don't think they actually called themselves that officially.

The Know-Nothings opposed all political organizations composed exclusively of foreigners and the exclusion of the Bible from government-funded schools; they considered slavery a local, not a national, issue but opposed its extension to new states.

A common enough stand at the time. Also, the state party may have opposed the expansion of slavery to the territories, but it's not in the national platform. Opposition to anything having to do with slavery would have broken the party in two.

As we found out a few days back, Know Nothing sentiment was so weak after the war that some new states admitted to the union allowed foreigners to vote, if they declared that they intended eventually to become citizens.

They began as the Native American Party but this year (1855) shortened that to the American Party.

Nicole Etcheson, "Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era"

This reply (not the one with the excerpt) posted using the old WWII ping list. May be the last time. If you want to be on the Civil War era list let me know.

Please keep me on the ping list. Thansk!

I’d love to be on the CW ping list. Thanks!

You're right, I have never heard of that provision.

from the article: "By 1856 -- after they successfully nominated, supported and won the Ohio's governor race with Salmon Chase, who would go on to become Lincoln's Treasury secretary -- they split over the issue of slavery; most of them entered into an alliance with the Republicans....

"Lincoln told Americans that immigrants may not be the physical descendants of the Founders, but they are their spiritual heirs:

The same forces which split and killed the old Whig party also killed the "Know-Nothings".

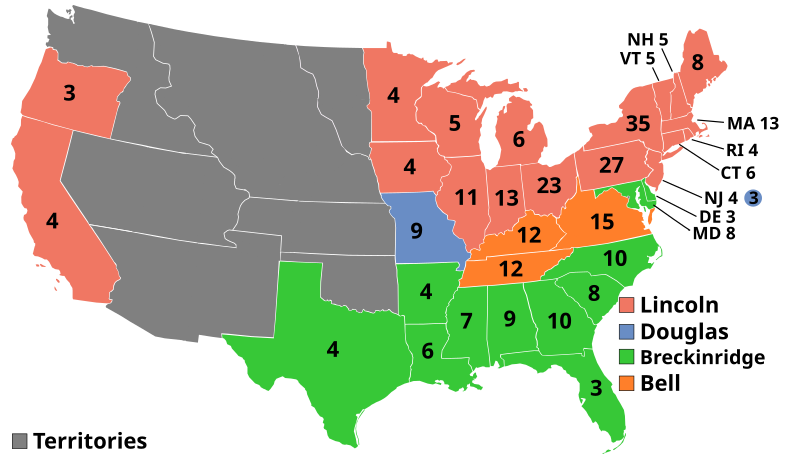

In 1860, those in the North mostly voted Republican, those in the South mostly voted for John Bell's Constitutional Union alliance with Know-Nothings.

They carried the states of Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee.

In 1860, the governor of Maryland, for example, was a Know-Nothing, and much as he disliked President Lincoln, refused to lead Maryland into the Confederacy.

So, Republicans have always had a "Know-Nothing" wing, but since Lincoln have been tolerant and encouraging of immigrants who want to become real Americans!

Know-Nothing Governor of Maryland 1858 - 1862, Thomas Hicks:

Please keep me on the ping list. Thank you!

Count me in too.

(Merry Christmas.)

Pingy.

Outstanding. Thank you sir.

Just for those who are interested, here is some background leading up to Bleeding Kansas that while not extremely detailed, does help set the stage for this topic at the survey level.

The issue of slavery in the colonies can be traced back to Jamestown. In 1619 a Dutch ship carrying slaves taking landed at the settlement to barter for supplies. When the ship departed, they left behind 20 African slaves. Some accounts state that this was in payment for the supplies taken, while others cite John Rolfe having confiscated them from the Dutch ship.

This left the settlers at Jamestown with quite a dilemma. At the time there were no laws or even rules concerning slavery in Virginia and in fact the first slave codes were still 40 years away. What should they do with these 20 African captives?

What they did have in Virginia was indentured servitude. In fact, the oldest known surviving servitude contract comes from that same year, 1619, when Robert Coopy of Gloucestershire, signed a contract agreeing to serve for 3 years from the day he landed in Virginia in return for save passage and the grant of 30 acres of land from his master at the end of the service.

So what became of these first 20 slaves? They became indentured servants. They would serve out their own servitude contracts and then go on to own land of their own. Some accounts even report that a few of them were successful enough to own indentured servants of their own.

As the colonies would progress, African slavery would become part of the make up of the English colonies. Massachusetts would become the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641 followed by Connecticut in 1650. By 1661 Virginia would also legalize the practice of slavery as indentured servitude had died out.

The practice of slavery would begin to die out though inside the next 100 years. It would begin in the north. The economy of the north, especially the agricultural economy did not lend itself well to slavery. Most farming in the north was either sustenance or market farming. When you are farming just enough to live on, you don't necessarily want another mouth to feed added to the mix and market farming is often small scale designed to be sold locally.

In the south it was another matter. Beginning with John Rolfe, tobacco began to form the basis of the southern economy. This would flow into other crops as the south grew. Indigo, sugar, rice, and eventually cotton would all become the economic backbone of the southern colonies/states. These are all commercial agriculture crops and they are all labor intensive crops. Both of these condition lent itself toward slavery as a form of labor to work this commercial interest.

In the north slavery would die out and even begin to be outlawed. Vermont would ban slavery first in 1777. Pennsylvania Quakers got the institution banned in 1780. Other northern states would follow with New Jersey passing a law for an eventual end of slavery in 1804. By the beginning of the Civil War that law still left 18 slaves living in the state.

It really looked like slavery would die out in the south as well. Globally the trend was working itself away from slavery. Even eventual ardent supporter of the "peculiar institution", John C. Calhoun, would say that slavery "like scaffolding of a building, [would] be dismantled after it had served its purpose." That would change in 1793 when Eli Whitney would invent the Cotton Gin. Whereas before the seeds from cotton had to be hand picked out which limited the production and size of cotton fields, his new invention in its original form could process 50 lbs of cotton a day. And that's just the hand cranked prototype.

Suddenly cotton became king in the south, and with it the need for labor to work the ever growing cotton plantations. Slavery went from a dying practice everywhere, to a necessary evil in the American South.

By 1820 this had become a major political issue. Which leads to the introduction of the Missouri Compromise of that year. Missouri had applied for statehood in 1818, but it was being resisted back in Washington by the northern free states. Why? Because in Congress, and especially in the Senate, slavery had become important enough that the balance of power in the Senate was of utmost importance. If Missouri was allowed to join the union as a slave state like they had applied, then it would shift the balance of power in the Senate toward the slave holding states (13 slave states, 12 free states).

The compromise, championed by Henry Clay (I often refer to him as the Buffalo Bills of presidential candidates), would split Maine off from Massachusetts admitting it as a free state and allow for Missouri to come in as a slave state. The balance would be maintained. Additionally, the remaining territory from the original Louisiana Purchase south of the 36°30’ parallel would be open to slavery and the territory north of that line (except Missouri) would be slave free.

The first half of the 19th century would see a deepening divide between the northern and southern states. One issue concerned tariffs. In 1828, Congress would pass a new tariff on imported goods that along with items like glass, and slate, included manufactured textiles. This would have a profound effect on the South. The southern economy was completely based on cotton. However, there was not much in the way of a textile industry for that cotton produced. The southern economy depended on the exportation of cotton.

Tariffs hurt this exportation business overseas and instead more cotton would be sent to the growing numbers of textile mills in the North. Manufactured goods produced in the north would then be sold back to the South, often at a price that was competitive with the rate of the imported (and taxed) goods. This caused a lot of animosity in the South especially around the importation of cheap, shoddy, fabric from Britain that was used to make clothing for slaves. Southern plantation owners felt that they were only exporting wealth, and mostly to the north at that.

This would lead to the idea of nullification and a test of the Constitution. Can a state nullify a federal law that is deemed destructive of the individual state? Vice President Calhoun decided to put the idea to the test on April 13, 1830 at a celebration of Thomas Jefferson's birthday. Calhoun was trying to judge the position of his President from Tennessee, Andrew Jackson. After multiple toasts that hinted to the rights of the individual states Andrew Jackson rose and gave a toast in which he stared down Calhoun and said, "Our Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun would respond to this with another toast, "The Union, next to our liberty, most dear. May we always remember that it can only be preserved by distributing equally the benefits and burdens of the Union." The die was cast between these two men, and Jackson's position could not have been clearer.

In July of 1832, Jackson signed the Tariff Act of 1832 which reduced the tariffs most harmful for the South, but it was not enough for Calhoun and his state of South Carolina. In November the state would pass the Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance would challenge Federal authority by nullifying both of the aforementioned tariff acts.

This would lead to a showdown between South Carolina, and the Vice President, and President Jackson. Secession was a term on Carolinian's lips and they pondered the possibility of leaving the Union rather than let Federal authority rule the day. On December 10th Jackson would issue Proclamation #26 to South Carolina. In this proclamation he would refute the claim by South Carolina that they can annul Federal law or refuse to enforce it. He also would caution them to retrace their steps before this escalated into something even far greater.

In addressing secession he warns South Carolina that the Constitution is a compact, not a league and therefore states cannot depart from it at their leisure. He warn them that secession is treason and that it will be treated as such.

By the end of December, Calhoun would resign as Vice President and Congress would pass the Force Act which would authorize the use of military force against any state the refused the enforce the tariffs acts. Henry Clay would step into the fray again and broker a deal known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833 which would be at least acceptable to all and serve to end the crisis.

As the north and south became more polarized more issues would serve as points of conflicts between the two factions. During the administration of George Washington, a law was passed to protect slave owners rights to retrieve slaves that had fled into other states. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 allowed members from a state to enter another state to retrieve escaped slaves. The only burden of proof they were required to give was an oral or written affidavit of ownership and the alleged escapee was not permitted to defend themselves. Additionally, any who harbored an escaped slave was subject to fines as high as $500 dollars. Quite a sum for the day.

Northern states would begin to violate this act in the 1800s and the resistance would only increase as the years passed. In 1836, the Massachusetts Supreme Court would rule in favor of escaped slaves in Commonwealth v. Ames which would declare that any slave brought into the state was automatically free.

Southerners would claim that this violated not only the Fugitive Slave law, but also Article IV, Section 2 of the Constitution which states "No person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws therof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service of Labour may be due."

In 1842, Prigg v. Pennsylvania would find itself all the way to the Supreme Court where it would be ruled that Pennsylvania was within its rights to prohibit its own magistrates from enforcing fugitive slave laws since the execution of the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution was exclusively a federal power and therefore had to be enforced by federal agents.

To add more fuel to the issue, in 1848 the Mexican American War came to an end and with it was a wide stretch of new land conquered from Mexico. A new question would immediately be imposed. Would slavery be allowed in the newly acquired territory?

Enter Henry Clay again. In one of his last acts in his long political life, he would compose a compromise to answer this question and others that were causing division between the north and the south. It had so much stuff in it in fact that if was going to be impossible to get passed through Congress. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas would take care of that by reworking this compromise into something that all side could agree to and hopefully put some of these issues to bed forever.

Included in the compromise was:

....California would be admitted into the Union as a free state.

....the slave trade will be abolished in Washington DC.

....a new tougher Fugitive Slave Act would be enacted

....and the territory acquired from Mexico with the exception of California would determine the existence of slavery based on Popular Sovereignty.

Though many felt this would put issues to rest, it would quickly show not to be so. The new fugitive slave law was by far the most divisive.

The new act allowed federal commissioners to issue warrants for the arrest of fugitive slaves and certificates for their return. The only evidence needed was an affidavit by the slave owner. The accused were denied the right to trail by jury and were not allow to submit any testimony in their defense.

That tracks close to the former act, but more was added.

If the commissioner determined that the accused was not an escaped slave he was paid 5 dollars for his work. If he determined that he was an escaped slave he was paid 10 dollars.

Anyone could be "deputized" to help capture accused escaped slaves (even abolitionists). If you refused to help, you would be fined $1000 and could be forced to pay the slave owner $1000 for each slave you failed to help retrieve, and could serve up to 6 months in prison.

This would immediately cause an outcry in the north by the growing abolitionist groups.

As for the other issue of popular sovereignty, after it was introduced in the Mexican secession, it was only a mater of time before the issue was raised again in those northern territories of the Louisiana Purchase. This would lead up to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, again championed by Stephen Douglas, which brings us up to date in our current story.

See, that’s why I put you on the ping list without the formality of asking you first. Thanks for that summary. I have a book on the Dred Scott case that begins with a history of slavery in the U.S. I will alert the group if it has tidbits you skipped over in your post.

Thanks Homer. I’m sure you will find many tidbits. One of the challenges of putting a class together is deciding what to leave out. You can’t cover everything. I tried to wrap that up in such a way where I didn’t get into things I knew we would cover later, like Dred Scott, Congressional fallout from Bleeding Kansas, and other things. Glad I could take a bit of time to write up this simple background for you. Time never seems to be a commodity anymore.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.