Posted on 08/09/2017 4:50:01 PM PDT by vannrox

Even though the modern world isn’t any more dangerous than it was thirty or forty years ago, it feels like a more perilous place. Or, more accurately, we inhabit the world today in a way that’s much more risk averse; for a variety of very interesting and nuanced reasons, our tolerance for risk, especially concerning our children’s safety, has steadily declined.

So we remove jungle gyms from playgrounds, ban football at recess, prohibit knives (even the butter variety) at school, and would rather have our kids playing with an iPad than rummaging through the garage or roaming around the neighborhood.

Unfortunately, as we discussed in-depth earlier this year, when you control for one set of risks, another simply arises in its place. In this case, in trying to prevent some bruises and broken bones, we also inhibit our children’s development of autonomy, competence, confidence, and resilience. In pulling them back from firsthand experiences, from handling tangible materials and demonstrating concrete efficacy, we ensconce them in a life of abstraction rather than action. By insisting on doing everything ourselves, because we can do things better and more safely, we deprive kids of the chance to make and test observations, to experiment and tinker, to fail and bounce back. In treating everything like a major risk, we prevent kids from learning how to judge the truly dangerous, from the simply unfamiliar.

Fortunately, we can restore the positive traits that have been smothered by overprotective parenting, by restoring some of the “dangerous” activities that have lately gone missing from childhood. The suggestions below on this score were taken both from 50 Dangerous Things (You Should Let Your Children Do), as well as memories from my own more “free range” childhood. If you grew up a few decades back, these activities may seem “obvious” to you, but they’re less a part of kids’ lives today, and hopefully these reminders can help spark their revival.

While each contains a element of danger and chance of injury, these risks can be thoroughly mitigated and managed by you, the parent: Permit or disallow activities based on your child’s individual age, maturity level, and abilities. Take necessary precautions (which are common sense and which I’m not going to entirely spell out for you; you’re a grown-up, not a moron). Teach and demonstrate correct principles, and supervise some practice runs. Once you’ve created this scaffolding of safety, however, try to step back and give your child some independence. Step in only when a real danger exists, or when your adult strength/dexterity/know-how is absolutely necessary. And don’t be afraid to let your kids fail. That’s how they learn and become more resilient.

In return for letting your children grapple with a little bit of healthy risk, the activities below teach motor skills, develop confidence, and get kids acquainted with the use of tools and some of the basic principles of science. Outside any educational justification, however, they’re just plain fun — something we’ve forgotten can be a worthy childhood pursuit in and of itself!

Playing with fireworks is not only a fun way to celebrate freedom, it teaches your kids how to responsibly handle fire and to have a healthy respect for exploding objects. Unfortunately, thanks to stringent fireworks laws and parents freaked out from viral stories of children losing eyeballs while lighting Roman candles, many kids today have never experienced the pure excitement and joy of igniting a fuse and waiting for the impending explosion.

Introduce your 3-5 year olds to the world of fireworks with “pop-pops” — those little paper-wrapped tadpole-like things you throw on the ground. They’re safe and the kids can have fun with them without injuring themselves or anybody else. You can also get them acquainted with sparklers. These preparatory “fireworks” offer a chance for children to learn general principles of safety: not to throw lit objects at others, touch people with a hot sparkler, handle a dud, etc.

When your kids hit age 6, you can start letting them light innocuous fireworks like snakes and smoke bombs. These don’t explode and will teach your kids how to light a fuse safely and to be aware of others as they use firecrackers.

By age 9 or 10, your kid should be ready to fire off pretty much anything you can find at a fireworks stand. You should continue to supervise their pyrotechnics until they’re teens, though.

Hammering a nail is a basic life skill every person should master, but many parents don’t let their kids attempt this task out of fear of them smashing their fingers. Yes, little children are uncoordinated, but the only way they’ll ever become coordinated is if they gain hands-on experience in using tools. Start letting your 3-year-old practice hammering nails with a ball peen hammer. They’re lighter than the traditional claw variety and thus easier to handle. As your child’s dexterity and strength improve, upgrade him to a full-sized claw hammer, lay out a 2×4 and a box of nails, and let him go to town.

Talk about cheap entertainment.

Sticking their arm out the window of a moving car and letting their hand ride the wind is a great way for kids to get acquainted with the basic principles of aerodynamics — it’s like a personal wind tunnel. Encourage your child to play with different positions — moving the angle of her hand, closing and opening her fingers — to observe how these variations affect lift and drag.

Yes, an arm could be severed if it hit an object alongside the road, but objects are very, very rarely positioned close enough to cause a collision. And if they are, your kid’s got eyes, doesn’t she?

When you jump from a cliff 20 feet high, you’ll hit the water at 25 miles an hour. That’s enough force to do some serious bodily damage. But making such jumps, and even those which are higher, is certainly doable, even for small kids, as long as you take precautions and teach them proper technique.

Make sure the water is deep enough; for a jump of 20 feet, the water should be at least 8 feet deep. Then add 2 feet of water depth for every additional 10 feet of jump height. Ensure the landing spot is free from underwater obstacles like rocks. And teach your child to jump in a pencil dive: body straight, arms overhead, back slightly arched to avoid rotating forward. For little ones who aren’t strong swimmers, put them in a life jacket before they Geronimo! into the water.

After watching a Robin Hood flick or reading The Hunger Games, your kids will probably want to shoot a bow and arrow. Instead of getting him (or her) the wimpy Nerf variety, let them use the real thing. A youth archery set can be found for less than $50, will provide hours of entertainment, and will teach your kids how to be responsible with potentially dangerous objects. They’ll also pick up skills like judging distance and how to aim.

Cooking might not seem that dangerous, but once your kids start wanting to help make dinner, you begin noticing how many tasks prompt a “Whoa, be careful there!” response. Sharp knives, stove fire, and hot pans present hazards. I remember when I was five, I decided to nuke a bowl of milk by myself; when I took the bowl out of the microwave, I spilled its scalding hot contents all over my arm. At first I hid from my mom, but as a huge blister formed, I had to confess and get it tended to by a doctor.

Despite such potential mishaps, it’s worth not only letting your children assist you in the kitchen, but allowing them to try cooking on their own too. More so than any other activity on this list, it’ll teach them a valuable skill towards grown-up self-sufficiency.

Few activities feel more liberating than climbing a tree. It’s thrilling to leave the ground and test your physical deftness, as well as your daring as you decide just how high up you’ll go. The air seems fresher among the branches. The most classic of classic childhood activities, hopefully tree climbing will continue on for another millennia.

Roughhousing may just look like a primitive-level melee of potentially injury-causing wrestling and hair pulling, but it actually has a bunch of high-level benefits. Whether children are mixing it up with Dad, or with each other, research has shown that good old fashioned horseplay develops kids’ resilience, intelligence, and even empathy — it teaches them how to negotiate the dynamics of aggression, cooperation, and fair play. So suplex your children more often, and don’t break up the good natured battle royales they put on between themselves.

Yes, it’s hard to believe this needs to be mentioned — that sledding isn’t an intrinsic part of every childhood (at least for those who live in colder climes). But I’ve met an alarming number of kids who grew up where there was at least occasional snow, and yet never went sledding. It’s hard to know if this is because parents are worried about the danger of the activity, or are just too lazy to leave their toasty, climate-controlled home to take the kids to a local hill. Either way, while sledding invariably comes with some bumps and bruises, as well as environmental discomforts, there’s hardly a more fun and memorable childhood activity. Especially when mitten-molded snow ramps are involved.

Not by themselves, mind you. Or on public streets, of course, which would be illegal. But in a big parking lot, largely free of obstacles, positioned on Dad’s lap, who can work the pedals and grab the steering wheel if needs be. From this position, a kid can experience the thrill of learning how to steer a 2-ton hunk of metal in relative safety.

There are many fun and interesting ways to start a fire without matches, but using a magnifying glass is one of the most versatile. It provides you with a focused beam of heat that cannot only burn paper and leaves, but melt plastic. A kid can even use it to burn a symbol or his name into a piece of wood.

According to one study in the U.K., while 80% of third-graders were allowed to walk to school in 1971, that number had dropped to just 9% in 1990, and is even lower today. Parents started prohibiting their children from walking or riding their bike to and from school by themselves out of the fear that they might be kidnapped along the way. Yet abductions are exceedingly rare, and no more common now than they were several decades ago. Further, a child has a 40X greater risk of dying as a passenger in a car than being kidnapped or killed by a stranger.

If letting your kid walk to school (or even the bus stop) still fills you with dread, work up to it gradually: 1) Walk together with your child to school a few times, pointing out any dangers from traffic and reviewing how to deal with strangers, then 2) walk halfway to school with your child, watching her walk the rest of the way alone, and finally 3) let her walk all the way by herself, without you watching.

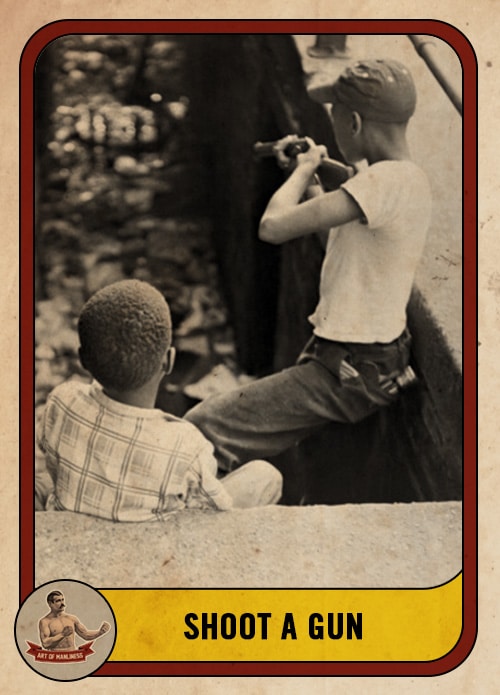

Guns and kids is an understandably sensitive topic, but we’d make the case that proactively teaching your kids how to safely use firearms is the best way to teach a healthy respect for them. When they’re 7 or so, introduce them to a pellet gun and begin teaching proper gun safety rules like keeping their finger off the trigger until they’re ready to shoot and treating every weapon as if it were loaded. Set up a a target (tin cans are fun) in your backyard and let them plink away while you watch. As they get a little older, they can tote around their BB gun by themselves. Don’t worry about them shooting their eye out!

When they reach about age 10 or 11, you can introduce them to a .22 caliber rifle or pistol. Again, this should be done under your supervision and you should reinforce good gun safety principles the entire time.

What kid hasn’t wanted to get a bird’s eye view of the neighborhood? Standing on the roof of your home is one of the more risky activities in this list, naturally, so supervise this vertical venture and take the necessary precautions: Only allow your child to attempt if your roof isn’t overly steep and is in good condition, without loose shingles and other potential hazards. Have your kid walk straight up and down the roof, standing with one foot on either side of its peak for stability, as they survey the landscape below.

Kate did this once in Vermont as a kid. At the exact moment she placed the penny on the track, a car in an adjacent parking lot happened to honk its horn; thinking it was the sound of an oncoming train, she jumped 10 feet in the air. Her family still laughs about it.

You do want to stay aware as you put your penny on a railroad track to be sure a train isn’t coming. If you’re going to wait for the train to come by and smoosh your coin, you also want to stand back at least 30 feet, as it could hypothetically come flying off and hit you. You don’t have to wait around for the train, though. If you decide to come back in a few hours or the next day to see what became of your penny, mark the spot with a stick before you leave for easy finding later on.

There’s a myth that a penny can derail a train, but that’s not true. You don’t want to put anything larger than a penny on the track, though.

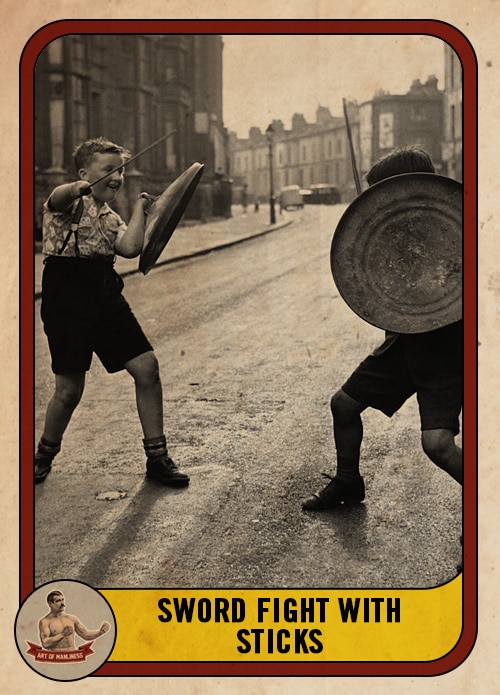

Parents are wary of anything involving sharp objects, sticks included. But letting your kid engage in some improvised swashbuckling is too fun an opportunity to pass up because of a negligible risk of injury.

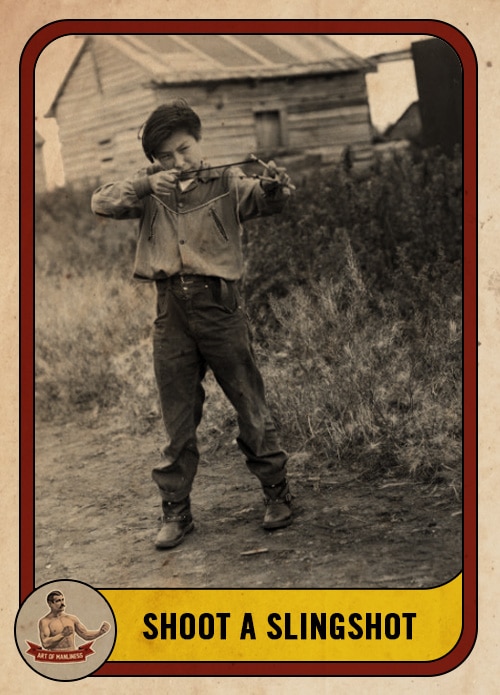

In a time not too long ago, the archetypical boy had a handmade slingshot dangling from the back of his pocket. Today, most boys have never touched one. Which is a shame because slingshots can provide hours of fun and they’re a great way to introduce firearm safety to your young ones (e.g., only point at what you plan on hitting).

Yes, you could just buy your kid a fancy manufactured slingshot on Amazon, but how about exposing them to even more positive danger by letting them make their own? (You can find instructions here.) They’ll learn how to handle a saw safely and get to practice some knife wielding skills to boot.

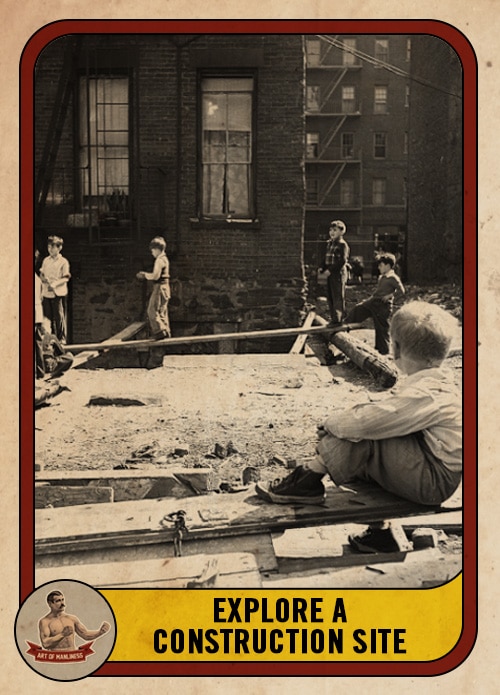

While I was growing up, the subdivision I lived in was still under construction, so there were always plenty of partially-built houses to explore. After the construction workers left for the day, my boyhood pals and I would cruise down the street on our bikes to check out their work and poke around the skeletal structures rising from the muddy lots. The ones that were the most fun to explore were the two-story houses. You’d have to climb up the railing-less, unfinished stairs and when you got to the top, you were able to walk to the edge of the second story’s framing and throw stuff down on your buds.

It’s a hard way to beat spending an afternoon.

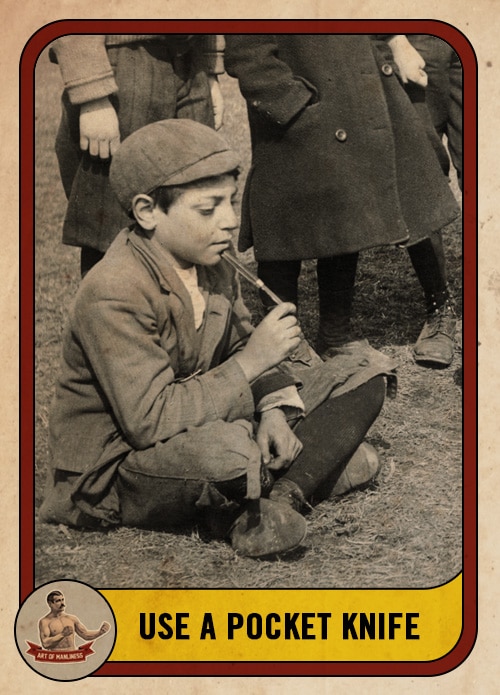

In Home Grown, author and homesteader Ben Hewitt describes how he gave his sons their first pocket knives at age four. Hewitt admits that he was worried that they would constantly slice open their pudgy toddler fingers with these sharp implements, but much to his surprise, his young boys rarely injured themselves. “There was something in the seriousness of the blade and the responsibility granted that transformed our son[s],” he notes. By giving them the responsibility of using a knife safely, Hewitt’s kids became responsible.

While you don’t have to give your toddler a pocket knife, consider letting them handle this trusty, handy tool sooner rather than later. It’s the only way they’ll learn how to handle sharp things safely and deftly, and doing so will open up new activities to them — from whittling to mumbley peg.

Many schools have banned certain physical activities from recess and P.E. class due to their being too “dangerous.” Football, dodgeball, tag…even all balls of any kind and running itself have gotten the boot in some places. Ropes have also been removed from many school gyms, due to the perceived risk of a child falling from the top — and probably also because of the risk of injury to the self-esteem of the kid who can’t even make it halfway up.

Climbing is one of the crucial physical skills everyone should develop, however, so if schools don’t provide the opportunity for its practice, then parents ought to, perhaps putting up a rope of their own in the backyard.

As a kid, taking your bike off a ramp is the closest you’ll get to flying without being on a plane. Back when I was a boy, my neighborhood posse and I built a big ol’ ramp out of a pile of dirt. We’d spend hours flying off that thing. For some reason, my favorite thing was to let go of my bike in midair and watch it continue to fly while I hit the dirt.

Building and riding off ramps will teach your kids some basic physics and even some construction skills. They’ll also learn, just as Napoleon Dynamite did, that if you’re not careful, taking your bike off sweet jumps can be hazardous to your junk.

There’s a primal connection between man and fire. Nurture that connection with your kids while they’re young. Let them play with matches and light candles when they’re pre-school age (with your supervision). They’ll learn that fire indeed burns, but from a flame so small it won’t hurt too much if it glances their skin. When they get to be about 8 or 9, let them build a fire all by themselves (still with your supervision, of course).

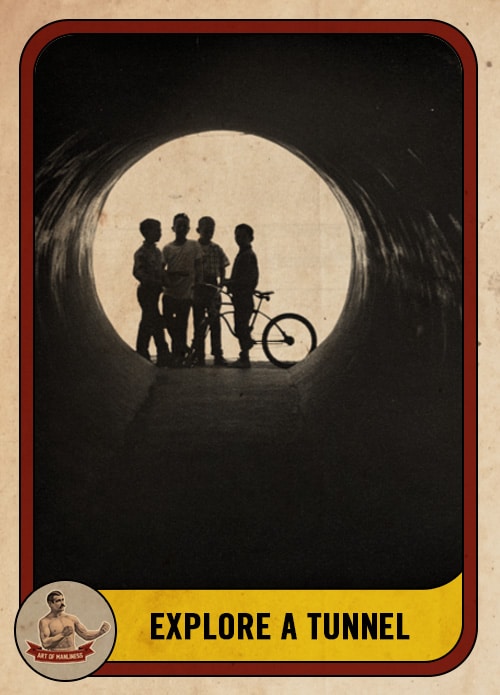

When my father-in-law was a boy in the early 1960s, the post-WWII housing boom was still in full swing, and a huge neighborhood was being built about a mile away from his home. Once the land was cleared, workers laid out gigantic sewer pipes so high he could walk through them without bending down, and so long they became pitch black once you advanced several yards from the openings. Though exploring the tunnels was a favorite activity of the neighborhood boys, my father-in-law recalls being a little terrified by these expeditions. Yet they still became an indelible memory!

Modern explorers should avoid tunnels filled with sewage and unsavory critters or humans, stay away from storm drains after rain, wear gloves, and bring along a flashlight — as well as a heaping helping of courage!

_____________

Magnifying glass photo courtesy of George’s Workshop

Penny photo taken by Eli Duke

Last updated: June 29, 2017

There was a kid-belief around that a penny on the tracks would derail the train. Sort of like the belief that you would get “blood poisoning” if you got stuck with an indelible pencil.

I was just stubborn, and not that bright. I had a lot of desire, drive, and persistence, but I didn’t think things through, got frustrated and angry easily, and got even more stubborn with each passing attempt.

It is odd to think on it. The thrill I got when I could navigate two obstacles...then three...then...wipeout. I just wanted to experience it so badly, to succeed at it...such a trivial thing. Now, I have a quarter-sized patch of scar tissue on the outside of each elbow from that series of days.

What probably did save me from fracturing my skull or worse was the fact that the skateboard would not stay together. I kept trying to fix it when the wheel assembly would come off. As an adult, I see how it works. As an 11-12 year old, all I could see was the desire to do it.

But I was stubborn. If you indulge me in this story below, it illustrates probably where that came from.

When I was perhaps 4 or 5, my mom served real mashed potatoes with raw chopped onions. I couldn’t believe it. It was the most disgusting thing I had ever eaten in my short life. The food made me actually gag. No way I was going to eat that. But I tried and tried. I cried. I hung my head and stared at the steaming pile of mash. I thought I was going to actually die, sitting there at the table, staring at those lumpy potatoes.

It turned into a struggle...a mental wrestling match between me, those animate potatoes, and my mother. I do not know how long in my life we fought, the three of us. My mother was trying to do what was right for me...I am pretty sure she thought that making me able to eat nearly anything I was served would make me grow, or something. So when she served them, I was expected to eat them. They would be added to my involuntary plate, and begin to take shape, peering back at me threateningly like Mount Suribachi.

I would eat everything around the potatoes, carefully leaving any contaminated foods exactly where they lay on the plate. Using a knife, I would surgically free the main body of the hamburger patty from the small edge that had unfortunately become ensnared in the base of the white mound. Any food so soiled was lost forever, completely inedible. Mom would watch me surreptitiously...carrying on normal conversation with everyone else, keeping one eye on my plate, on the potatoes. As long as there was some other tidbit of food on the plate, or a mouthful of some liquid that could be sipped...confrontation was avoided.

But I could only sip at a glass of milk, each sip smaller and smaller than the previous one, until finally it was me in one corner, and the potatoes in the other. I would settle in, hunch my shoulders for conflict, and lower my head. Body language transmitting at high frequency, the signal flags were raised, and the battle was joined. Slowly, everyone else would finish dinner, dessert was served, and plates were removed. The lights would go down, and soon it was just me under the white light which shone brightly down on the potatoes. The sentries were posted on the ramparts, and the long siege began.

There were many times I tried to avoid this standoff. Occasionally, I would attempt to stealthily feed them to the dog under the table. I thought this was a brilliant idea until I tried it. The problem is, dogs just do not enjoy mashed potatoes with raw chopped onion. To avoid a real conflagration, I would have to retrieve the uneaten lump of dog-proof potato on the floor before my mother saw it. I would put it back on the plate, secure in the knowledge that now I really WOULD have to die before I would put those drool covered potatoes into my mouth.

Another time, I attempted to conceal the potatoes in my mouth and transport them into the bathroom during a sanctioned toilet break. There, I could drop them in the toilet, flush, and be free of...a mouthful. What then? Next time, I would fill my mouth until I must have looked like a chipmunk with mumps before I went to the bathroom. The basic, insurmountable flaw of this approach was that the mere act of putting the onion laden mash into my mouth was very nearly just as disgusting as chewing and swallowing. The gag reflex under that much pressure made for a memorable potato pyrotechnical show. That was a dead end.

As I got more experienced, I attempted mind over matter. It was me and the potatoes. As we stared each other down, I would get angry. I began to work myself up. I could do this. I could do anything. This was easy. I found that if I did not chew them and experience a nausea inducing crunch of raw onion between my molars, I could actually attempt to swallow them without chewing. This seemed like a good thing to try until I actually tried it. My mother would stare at me in amazed horror and disgust as I gagged.

But she made me sit there until they were gone. So, I would settle in for the long haul. I would hunker down, and stare at those potatoes. Life would go on. Television was watched, toys were played with, pajamas were put on, and eventually my mother would take the plate and send me to bed. I was never so happy in my life at that point. This went on time and time again for years.

At some point in my life, my mom gave up. I truly cannot say if the war lasted one month or six years. I have no idea. In any case, I think it was a very good truce for both of us. It freed her in some way, and I was able to sit at the table and enjoy meals. And I love her dearly for it.

To this day, my older brother says: “We thought you were amazing, you were so stubborn, and would just sit there for hours staring at those potatoes until mom would finally give in. We really admired how stubborn you were!”

I might add: whittling; and how to sharpen a knife.

Hahahahahahaha! The infamous splintering plywood ramp!

Heh, for other kids, I am sure they could look and say “That ain’t gonna work!”

But to me, I was absolutely surprised every time it failed, which made the collisions with trees, fences, the ground, and other kids all that more painful. I could never, ever prepare myself in advance for failure, so I was always “unexpectedly” hurt!

As an adult, I realize now I simply couldn’t think 60 seconds into the future to consider what it might hold should something go wrong.

Now, as an adult, when I hold that small screw over a carburetor throat, a voice says “Ummm...you should probably put a piece of tape or something over that in case you drop the screw...”

In the past, I was always astonished to see that screw slip out of my hand and disappear into that dark bore!

Everything but the sled before 8. Seriously. I’m 40 and have never been on a sled

In my rock and fossil collection I had (still have) a large asbestos rock with all the fibers sticking out everywhere. Brought it to school and passed it around as per direction by the teacher (early 1960’s)

Oh my God, I thought I was the only one!

I absolutely HATED mashed potatoes (still do). I was always afraid they would make me throw up. Baked potatoes are almost as bad.

I went through the same struggle with my mom, not quite as epic as yours, but a struggle nonetheless.

Re the screw and the carb—I thought I was the one who ever did that!

HAH!

Was able to get it out though. Phew!

I did all these things as well. You need to be able to handle danger without going all ‘snowflake’. The only way you can learn to handle danger is by handling danger.

I’m a girl, and I did a lot of those things. Add to the list: swam in a creek in the summer, and skated on it in the winter; built a stage out of lumber hauled home from a construction site and rammed a screwdriver into my hand; rode my bike everywhere. I sat in a lot of trees.

I’m going to start referring to myself as a “free-range kid”.

Well,if you grew up in Louisiana or Hawaii that's understandable.But most Americans know sledding.Yes,it can be dangerous (I had a few narrow escapes) but God it's fun!

You’re off to a wonderful start.

Can you take him fishing; dig the worms and learn how to put them on a hook. Gut the fish....and pan fry them?

I would get him a jack knife; even if his parents won’t let him take it home; leave it at your house and build on those skills each time he comes.

Mumbley-peg. :)

Yeah, the clamp-on roller skate - turned skateboard. I think that idea goes back to the pre-WWII years and although California is likely the home of the first such contraption, they seemed to spring up in any port city that handled citrus fruit. There's a picture of my dad with a citrus crate scooter (orange crate, label and all, nailed atop the skateboard as a "handlebar") near the river in New Orleans, where he grew up. Some woman that lived up the street would scatter gravel on the sidewalks to keep the noisy metal-wheeled scooters away, but they figured out how to attach an angled board to the front, skimming low over the sidewalk, that would shove all the gravel off of the concrete.

Most are fine but most constructions sites are locked up tight now days for reasons of liability.

Ping

I’m seventy years old. I don’t know how I survived childhood. I should have been dead or blind before reaching the age of 14.

But then it taught us to be careful!

When was the last time you saw K-6 kids, boys and girls with a scabbed knee or elbow or two? A black eye?

Back in the day, if during the summer you hadn’t scrapped your knees several times then you weren’t serious about having fun nor playing hard enough.

A black eye didn’t always mean one was fighting, sometimes caused by rough housing, a missed ball or whatever.

Got our minor wounds and continued on with the games. Come supper time moms would take inventory of the wounded, apply iodine and band aids as necessary before sitting down at the table.

Cliff diving...For some forgotten reason my pre-school cohort had taken to dropping from the sides of outdoor stairs...not steps but full one story high. We’d climb over the railing, hang from the platform and drop. That was it. Run back up the stairs and do it again. Exhilarating overcoming the initial fear No broken bones, maybe a twisted ankle or two. Now days a police patrol would be called out with a suicide counselor telling us not to jump, parents would be investigated by social services and local news crews would be “concerned”.

I did every one of those things as a kid except riding a bike off of a ramp. I rode a bike into a swimming pool, we did not have a bike ramp.

I did too. We built our own ramps.. Didn’t jump off a cliff though. Jumped off roof instead..

I let my sons do lots of boy things. We lived surrounded by woods. They had a lot of fun and learned as well.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.