Skip to comments.

Electrical engineers on the brink of extinction threaten entire tech ecosystems

The Register ^

| 18 July 2022

| Rupert Goodwins

Posted on 07/19/2022 10:23:31 AM PDT by ShadowAce

Intel has produced some unbelievable graphs in its time: projected Itanium market share, next node power consumption, multicore performance boosts.

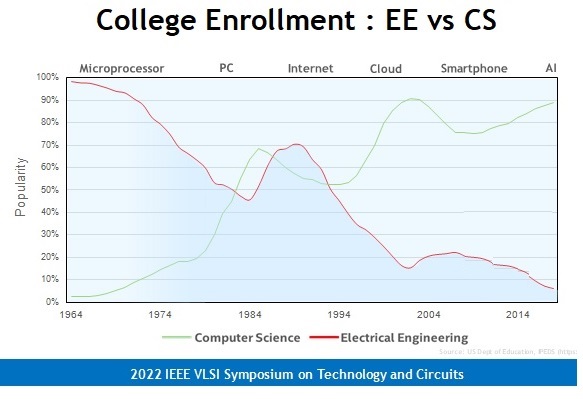

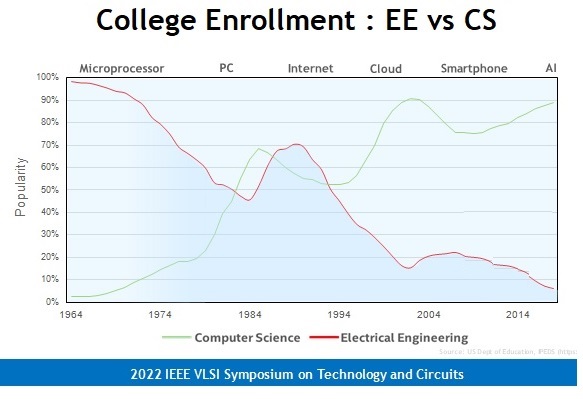

The graph the company showed at the latest VLSI Symposium, however, was a real shocker.

While computer science course take-up had gone up by over 90 percent in the past 50 years, electrical engineering (EE) had declined by the same amount. The electronics graduate has become rarer than an Intel-based smartphone.

Engineering degree courses are a lot of work across a lot of disciplines, with electronic engineering being particularly diverse. The theoretical side covers signal, information, semiconductor devices, optical and electromagnetic theory, so your math better be good. There's any amount of building-block knowledge needed, analogue and digital, across the spectrum from millimetric RF to high-energy power engineering. And then you have to know how to apply it all to real-world problems.

This isn't the sort of course you opt to do because you can't think of anything better. You have to want to do it, you have to think you can do it, and do it well enough to make it your career. For that, you need prior exposure. You need to have caught the taste. And to make it your life, there has to be a lot of high-status, high-wage, high-interest jobs to do at the end.

For most of the history of electronics, there was a clear on-ramp for this, and an industry that didn't need to sell itself because it was inherently cool for geeks. Look at the biographies of the great names in electronics, such as Intel co-founder Robert Noyce or the father of the information age Claude Shannon, and you find them as teenage geeks pulling apart, then rebuilding, then designing radios and guitar amplifiers. The post-war generation tore down military surplus gear to teach themselves how it worked and mine components to build their own inventions.

This was practical magic, and you could start your apprenticeship by taking the back off a broken wireless. If you had the urge, it was easy to ignite the fascination. Then came the pull of working on the front line of the Cold War, the space age, the era of technological innovation. The industry had its supply of fresh creativity guaranteed.

This remained broadly true until the turn of the 21st century. A reasonably bright kid would realize that the family CRT television was in fact a particle accelerator with its own multi-kilovolt high-voltage generator, plus any amount of repurposable bits and pieces. You can have a lot of fun with that. There were old analog gadgets all over the place. You could peer inside Granny's radio and follow the signal path, component by component. That's all gone now.

By one measure we're surrounded by more electronics in our homes than entire nations had years back. Your granny's radio had maybe 10 transistors; a smart speaker, billions. But it's a computer, like your flat-screen television is a computer, like your phone and your audio system and even your light bulbs are computers. The electronics have sunk out of sight, beneath thick alluvial layers of software, and it will do nothing without that software. Any budding geek will expend their youthful vigor on that software first, because it's where the animating genius of technology now resides. We have literally cut ourselves off from a primary wellspring of fascination.

It's not all bad news. Maker culture is alive and well and access to knowledge has never been easier. You don't have to go to a library to get out books on electronic theory or find a fascinating gadget to eviscerate. It's all on YouTube. Want to take apart a laser guidance system for an RAF Tornado's bombs? Mike's Electric Stuff has you covered. But the maker culture revolves around embedded processors and high-level concepts: you can build radios at home now that cost a few pounds and outperform the state-of-the-art of a few years back, but they're software defined.

If electronics are invisible at the start of a young engineer's life, they're invisible in the careers they may contemplate. In the 20th century, not only were consumer electronics full of differentiated analog desirables, aerospace, the military, and industry were too. Now everything is a screen with a UI. You still need a lot of specialized hardware, but it's vanished deep into the background. No wonder everyone who once had the itch to solder now gets ensnared by software.

Is it possible for electronics to regain its status as a primary inspiration for young technical minds? Not without a lot of work from the industry that needs those minds. The pipeline it once took as the natural order has broken. To reach new talent, the magic must be re-exposed. What goes on in chip fabs, design bureaus, and product R&D is just as important – and as magical – as ever.

Selling that message in a world designed by geeks to distract geeks is going to be hard. But we have hero brands, and hero space missions, and temples where we conjure machines, atom by atom. If the industry can't look at all the incredible things it does and find a way to capture imaginations, it deserves every last heartbreaking graph of doom. ®

TOPICS: Computers/Internet; Hobbies; Science

KEYWORDS: ccp; china; demagogicparty; getwokegobroke; h1b; hardware; ibew; stem

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-77 next last

To: Honorary Serb

“But I don’t know how many students are in electrical engineering (Course 6-1) vs. the various computer science majors. Does anyone here know?”

EE students are a handful compared to CS/IT students; probably 1:100.

21

posted on

07/19/2022 11:00:48 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: central_va

22

posted on

07/19/2022 11:01:30 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: central_va

“”hi” tech made their curry, now eat it.”

Nice! Well said.

23

posted on

07/19/2022 11:02:00 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: bert

My son got his first degree in economics. After he realized that was no way to make a living he went back and got his EE degree. Now he specializes in shutting down facilities before they’re dismantled.

24

posted on

07/19/2022 11:03:27 AM PDT

by

dljordan

To: AnotherUnixGeek

I did both EE and CS together. I did EE work through 1992, but primarily CS since with some EE work here and there as needed. The EE helps in systems design work. The EE world has went automated for the most part. Design the logic and software designs the circuits, PCBs, etc.

25

posted on

07/19/2022 11:03:52 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: Bobalu

“Yup, physics/math types are pretty much already EE’s to some degree...”

Not really. There is about a 25% overlap between physics and EE, but circuit design, RF, etc., are still the realm of the EE. (I hold bachelor’s and graduate degrees in EE, CS and physics)

26

posted on

07/19/2022 11:08:28 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: dljordan

That’s they way it is with engineers. Some are designers but many perhaps most do all sorts of jobs and tasks that require engineering knowledge and discipline.

27

posted on

07/19/2022 11:11:48 AM PDT

by

bert

( (KWE. NP. N.C. +12) Juneteenth is inequality day)

To: ShadowAce

EE is a very challenging (hard) major

And not every American wishing to undertake a EE degree can get in. Many of the leading USA universities have filled up their engineering schools with foreign students.

We are, to a considerable degree, educating the next geneation of engineering talent for Communist China (mostly) and other foreign countries.

28

posted on

07/19/2022 11:14:49 AM PDT

by

faithhopecharity

(“Politicians are not born. They're excreted.” Marcus Tillius Cicero (106 to 43 BCE))

To: ShadowAce

Wow, that IS shocking. I had no idea. Without hardware, what good is software?

Isn't it rather ironic that the idiotic "green" revolution is going to depend more than anything on EEs just as they are going extinct?

The "green" revolution is also going to be stymied by a lack of mining and mechanical engineers because there aren't enough copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, and rare earth element mines to meet surging demand for minerals. The mineral demand is set to jump SIX times when the green revolution takes off. The Soviet central planners are failing as usual.

"We Need 6 Times More Minerals to Meet Our Clean Energy Goals", by Dharna Noor, May 6, 2021

29

posted on

07/19/2022 11:15:15 AM PDT

by

ProtectOurFreedom

(“...see whether we in our day and generation may not perform something worthy to be remembered.”)

To: faithhopecharity

We are, to a considerable degree, educating the next geneation of engineering talent for Communist China (mostly) and other foreign countries.IMO all of the free college is crap. Loan forgiveness is crap. Having said that, any US citizen that wants to take on getting an EE degree should get a free ride care of the taxpayer.

30

posted on

07/19/2022 11:17:27 AM PDT

by

central_va

(I won't be reconstructed and I do not give a damn...)

To: cherry

“All you wanna do is learn how to score!”

31

posted on

07/19/2022 11:18:49 AM PDT

by

dfwgator

(Endut! Hoch Hech!)

To: ShadowAce

Your granny's radio had maybe 10 transistors; a smart speaker...My granny's radio had vacuum tubes...

32

posted on

07/19/2022 11:19:04 AM PDT

by

GOPJ

(US Military Promotions - Advancement based on ‘sexual kink, weirdo status, and skin pigmentation.)

To: ShadowAce

Your granny's radio had maybe 10 transistors; a smart speaker...My granny's radio had vacuum tubes... That said, EE needs to be folded into computer science so institutional knowledge isn't lost.

33

posted on

07/19/2022 11:20:01 AM PDT

by

GOPJ

(US Military Promotions - Advancement based on ‘sexual kink, weirdo status, and skin pigmentation.)

To: ShadowAce

Differential Equations. No thanks

That’s why I went Civil Engineering

34

posted on

07/19/2022 11:22:41 AM PDT

by

shotgun

To: Paladin2

Any field which has to have ‘science’ in its name, isn’t...

35

posted on

07/19/2022 11:23:08 AM PDT

by

Chode

(there is no fall back position, there's no rally point, there is no LZ... we're on our own. #FJB)

To: CodeToad

Do you know this, or are you just speculating?

36

posted on

07/19/2022 11:24:20 AM PDT

by

Honorary Serb

(Kosovo is Serbia! Free Srpska! Abolish ICTY!)

To: Honorary Serb

Know it from experience. If you need an accurate and reliable answer I suggest you don’t take your answers from social media websites like FR and, instead, seek official numbers from the universities.

37

posted on

07/19/2022 11:28:48 AM PDT

by

CodeToad

(Arm up! They Have!)

To: maro

I was a physics major (also CS, but I digress)

It has amazed me how often that knowledge becomes useful when programming real-world applications.

38

posted on

07/19/2022 11:28:52 AM PDT

by

Mr. K

(No consequence of repealing obamacare is worse than obamacare itself)

To: ShadowAce

Intel had enough $$$ they could have setup their own University back 15 years ago to train future American Engineers.

It would have given a place for retired Intel engineers to teach and would have replenished the engineers now retiring.

Instead they believed the nonsense that India could supply all their needs.

The good news is Pat Gelsinger now sees this was a major mistake and is trying to address it.

Probably too late as demand for experienced analog design engineers is thru the roof at the same time they are starting to retire.

39

posted on

07/19/2022 11:29:37 AM PDT

by

Zathras

To: CodeToad

40

posted on

07/19/2022 11:44:55 AM PDT

by

Honorary Serb

(Kosovo is Serbia! Free Srpska! Abolish ICTY!)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-77 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson