Posted on 12/02/2018 5:13:05 AM PST by LibWhacker

Have you ever stopped to wonder exactly how much light has been produced by all the stars in the Universe, over all the time that has passed? Well, now you can wonder no more. An international team of astronomers has actually calculated the amount of starlight in the cosmos.

And it's teaching us new things about the early years of our Universe. In the time since the Big Bang - roughly 13.7 billion years - our Universe has produced many, many galaxies, and many more stars. Perhaps around two trillion galaxies, containing around a trillion-trillion stars. For decades, scientists have known that knowing how much light these stars have produced over the course of the Universe's lifespan would be a powerful tool for understanding the early Universe, as well as the history of star formation. But, well, it's not exactly an easy thing to measure. While there are a lot of stars out there, producing many photons, space is incredibly vast, and starlight incredibly dim. There's also interference from zodiacal light and the Milky Way's own faint glow. The Universe's starlight cannot really be observed directly. But astrophysicist Marco Ajello of Clemson University and his team discovered an indirect method of quantifying starlight. They used gamma ray photons. "These are photons that are high energy, typically a billion times the energy of visible light," Ajello told ScienceAlert.

"While travelling through space, gamma rays can be absorbed through interactions with starlight photons. And if there are many starlight photons, there will be more absorptions; so we can count the number of absorptions that we see to understand the density of the starlight of the photon field between us and the gamma ray source." Using nine years' worth of data from NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, Ajello and his team analysed the light from 739 blazars (strong gamma-ray sources) throughout the Universe to determine the rate of absorption into the extragalactic background light (EBL), the Universe's accumulated background radiation. This gave them the density of starlight photons in the EBL - and, because the blazars are at different distances, they were able to do so across a range of time periods. Once they accounted for and subtracted light from other sources, such as the glowing accretion discs around supermassive black holes, they could multiply this density by the volume of the Universe to arrive at the number of photons produced by stars since the beginning of time.

"We basically have a tool, like a book, to tell the stories of starlight across the history of the Universe, and finally we found it, and we can just read it," Ajello said. "So we did. We measured the entire star formation history of the Universe." It is pretty simple to explain, but it was painstaking and complex to actually do. It took the team three years - and it was worth it. We now know that, as of the time Fermi's data was collected, the Universe's stars had produced 4x1084 photons. Do you need that spelled out? Here: 4,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. Yep, it's a four followed by 84 zeroes. That's a pretty cool trivia fact, so file it up your sleeve for later. But you bet the science actually gets much cooler. Because that cool number actually lifts the veil on a particularly mysterious time in our Universe's history - the Epoch of Reionisation, which started around 500 million years after the Big Bang. We often hear the term "holy grail" chucked around, but the EoR really IS one.

It's basically when the Universe's lights switched on. Before the EoR, space was opaque. Then something came along and ionised all the neutral hydrogen, so that radiation - including light - could stream freely through the Universe. "With our measurement, we can reach the very first billion years of the Universe, and that's a very interesting time of the Universe, so distant from us that all the really powerful telescopes can't really see. The objects there are so far away and so faint that we can't really see them. Instead, we still see the light from those objects," Ajello explained. The team found two things of note in that time: a very large number of UV photons, which was expected for the reionisation process; and that the sources of those UV photons were populations of irregular galaxies - small, blobby, asymmetrical galaxies that produce a lot of UV radiation. These could be the drivers behind reionisation. It's expected that the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for a 2021 launch, could tell us more about the EoR. Meanwhile, Ajello and his team are going to apply their book of the stars to a deeper study of the cosmos - such as the rate of the Universe's expansion, the Hubble constant, which has been really difficult to pin down. "It turns out our measurement is very sensitive to the expansion rate of the Universe," Ajello said. "This can be used to make a measurement of the Hubble Constant right now, so that's something that we're going to do." The team's research has been published in the journal Science .

Well I guess you have to teach the monkey to put a button once every second. Not sure about protons - do they make things go all blooie?

Just wondering how long these "scientists" estimate it took for the Big Bang to go BANG and why?

Not sure about protons - do they make things go all blooie?

Well, they do in photon torpedoes.

I wonder if they added those in?

Well, they do in photon torpedoes. I wonder if they added those in?

Not mine. I bought mine in the parking lot at the gun show...loopholes, you know. ;>)

Oh, I forgot about those. We used to buy them across the

line in Alabama at little roadside stands.

They were the BIG ones. It was either that or find some

railroad torpedeos but they were dangerous and you had to

set them off by dropping a sledge hammer on them.

Sorry, but this kind of thing is 90% guess work. Calling it a fact, is in fact, an error.

After reading through some of the replies, another question comes to mind... We have AAA, AA, (apparently)B, C, and D batteries. It all seems logical and orderly, but then, why do we call a 9-volt battery a 9-volt rather than some other designation? I'm sure some freeper will know.

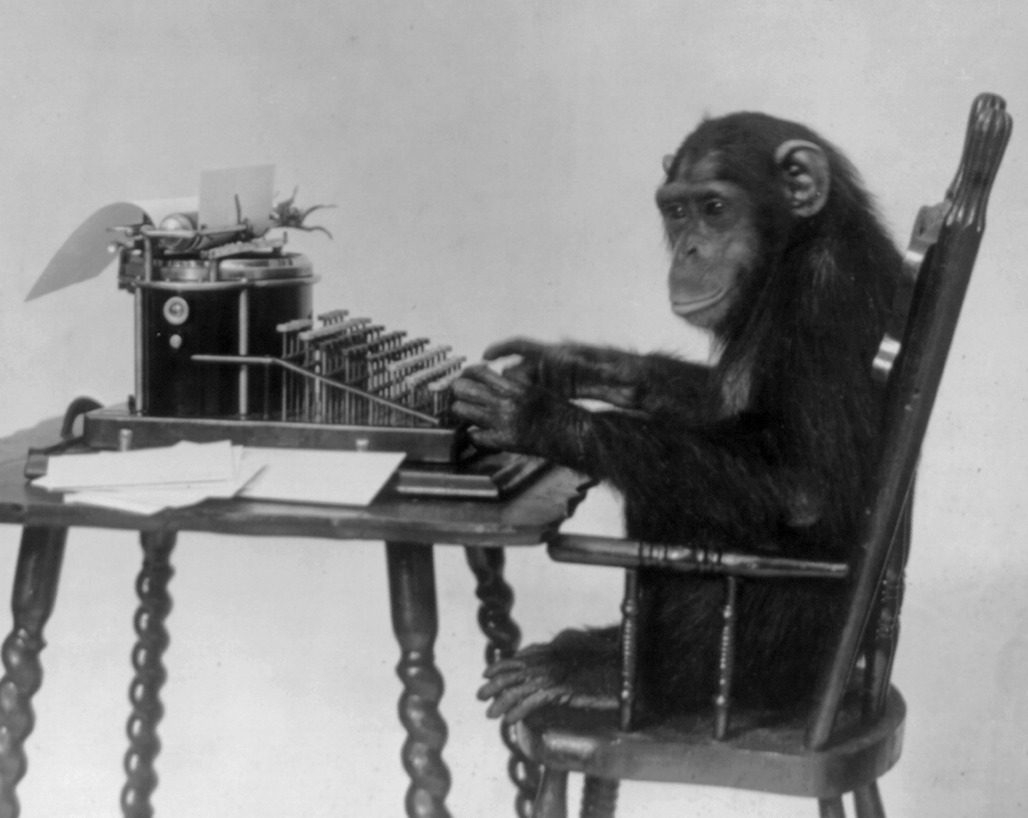

Yes... and they have some ideas. Surprise, surprise, science takes time! Betcha didn’t know that. They’ve been working on it for thousands of years, and no doubt they’ll be working on it for thousands more. They surely have more and better ideas than the two-digit-IQ ignoramuses who belch loudly and think they’re being clever when they blow farts in the direction of a scientist. Monkeys are more clever and more interested in the world around them. Thank God our progress hasn’t depended on them else we wouldn’t have fire or the wheel or anything else, and we’d still be picking lice out of each other’s fur.

Well , I am so far ahead with my vision that I turned my front door peephole device around!! I can see people coming 469 yards away!!!!!! Now the practical application of their “guesstimate” will probably dictate how many lumens the tail and headlights of the intergalactical ships will need in order to avoid mid space collisions...anyhoo I may not have a degree in light absorption of the cosmos BUT , I did stay at a Holiday Inn fourteen years 23 days 6 hours 12 minutes and 31 seconds ago as of ......NOW! 2:24 PM exactly CST. I’m a stickler ya’ know.

If you want some real fun try explaining firearms caliber terminology to the uninitiated sometime.

Can't say that I have actually.

However, I have often wondered how many trees there are here on planet Earth and nobody seems able to come up with the answer for that.

Even the number of trees in Maine, it appears that nobody really knows. And that bothers me.

This I do not buy. For to do this, the monkeys would be able to need to feed paper into a typewriter.

Has anybody ever seen a monkey feed a piece of paper into a typewriter? Not to mention change ribbon and any number of tasks related to operating and maintaining a typewriter.

They would have liberals with baskets around their necks filled with ribbons. The paper would be on huge rolls so no feed problems there; it’d be all about cutting enough trees fast enough to satisfy the paper manufacturing.

Ha, three trillion! => https://greenfuture.io/nature/how-many-trees-are-in-the-world/

.. and the article that you read was written and typed by those very same monkeys, entitled "How We Done It"

Lol, good point. We’d have to ask the author what she meant... Have minds been blown because the number is so large, or because scientists were able to figure it out in the first place?

No thanks. I sometimes have issues with keeping stuff like that straight myself.

In Japanese, “photons” means ‘many farts fired off in rapid succession in a crowded elevator.’

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.