Posted on 01/23/2025 8:20:35 PM PST by SeekAndFind

Within days of taking office, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that has been misconstrued by most of the talking heads out there as "ending birthright citizenship." This characterization uses an overly broad brush to paint over what is actually an extremely nuanced issue with regard to the interpretation of citizenship in the 14th Amendment.

Section 1 of the amendment starts off with one of the most consequential lines of any of the Reconstruction Amendments passed in the wake of the Civil War: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

What Trump's executive order does is limit the interpretation of that line in the legal sense. In the order, Trump directs the government not to legally (through documentation, etc.) recognize the citizenship of anyone "(1) when that person’s mother was unlawfully present in the United States and the person’s father was not a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of said person’s birth, or (2) when that person’s mother’s presence in the United States was lawful but temporary, and the person’s father was not a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of said person’s birth."

In other words, if the parents are not in the United States legally, then the child is not automatically granted citizenship.

The executive order was immediately challenged in court in several states, with groups like the ACLU latching themselves onto the cause, and the Trump administration has already lost in at least one federal court. The judge in that case strongly rebuked Trump's actions.

"I’ve been on the bench for over four decades," Senior U.S. District Judge John C. Coughenour said. "I can’t remember another case where the question presented is as clear as this one. This is a blatantly unconstitutional order."

Coughenour (probably) has a point. The president cannot unilaterally reinterpret an amendment, especially on a question that the Supreme Court had previously settled. But the Trump administration isn't seeking to just unilaterally change things. It appears his team wants to take this all the way back to the Supreme Court.

But why?

The Supreme Court answered the question of birthright citizenship in the late 1800s, in United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Wong Kim Ark was born to parents who were legal residents, though not U.S. citizens, living in San Fransisco at the time. The family left America, though Wong came back and was denied entry into the country.

He sued, claiming he was a citizen, and the case went before the Court. Here is what they found:

The question comes down to one particular phrase in the amendment: "subject to the jurisdiction thereof." The Court interpreted it, like most do, to mean that everyone born in the U.S. was automatically "subject to the jurisdiction thereof," making them legal citizens. Some legal scholars, who agree with the Trump administration, argue that it means only those who are "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" (meaning those whose families are legally in the United States) are recognized as citizens.

The Trump administration could push this ahead, fighting to keep the issue alive all the way to the Supreme Court, forcing the current Court to re-evaluate what the previous Court ruled.

There are really two ways that the change to our interpretation of birthright citizenship can happen. The first is through an act of Congress, which will probably never happen. The second is to get the Supreme Court to amend or overturn its previous ruling, which is difficult but not impossible.

There are two objectives here:

If the Trump administration can convince the Justices to narrowly re-define the legal interpretation of the 14th Amendment, then his executive order will, in fact, have worked - even if the process by which he got there skirted the lines of constitutionality in the first place.

Trump's problem is that he has essentially, two years to get things done. The midterm elections could result in Democrats retaking the House or Senate, and if that is the case, then he loses the opportunity to get much more of his agenda accomplished. Getting Congress to devote time to birthright citizenship takes away from his ability to get other things done, so he has to take the long way around - through the courts, that is.

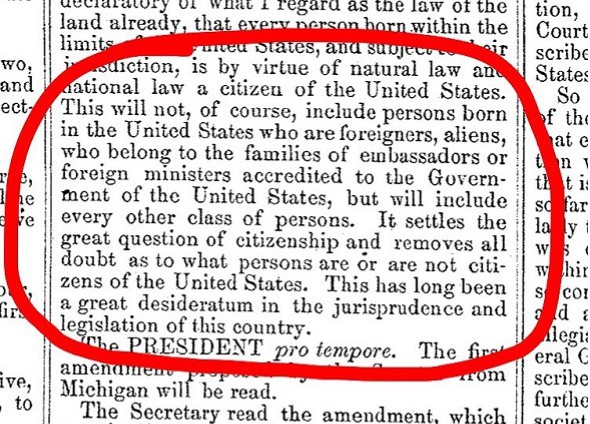

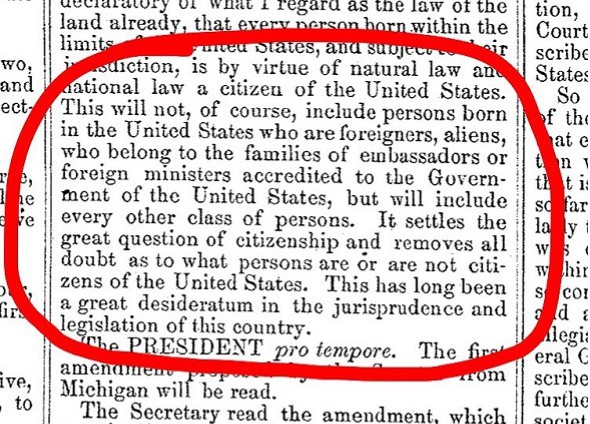

He certainly could pull it off. He has just the right Supreme Court makeup to have a chance. The originalists on the Court will undoubtedly take a look at the fact that the original intent of the 14th Amendment was to apply to people legally in the U.S. (a fact that is in the congressional record, if you go and read up on what the authors of the amendment were discussing at the time). But it's still a tall order.

In all honesty, I'm not convinced it's the battle we should have right now. There are more immediate and critical needs in the fight to fix the immigration issue than to tackle birthright citizenship. However, it is something he promised, and he wants to deliver on it.

It's one of those long-game plans. This will have very little impact in the near future, but could work long-term to dissuade birth tourism in the U.S. For immigration hawks, it's a vital piece of the strategy to reshape how America controls its borders and protects its citizenry.

You can’t win if you don’t play.

With Roberts and Barrett almost certainly siding with the three leftists, I doubt it.

Federal judge halts Trump's executive order ending birthright citizenship

WBAL ^ | 01/23/2025 | MIKE CATALINI

Trump understands a lesson the Bushite GOP never was willing to learn. Sometimes in politics you fight a battle knowing your are probably going to lose to show your voter base you take their concerns seriously. You also fight the battle to provoke a debate and more public opinion towards your viewpoint.

Not fighting a political battle because you afraid to lose, is an automatic loss, something the GOP-E still does not understand.

Not a chance. I wish the 14th Amendment read differently than it did, but the only reason this may not make it to the Supreme Court is that all of the Circuits likely will agree on striking it down, so there is no reason for SCOTUS to take the case.

They need to argue that the 14th Amendment was written for individuals who had no allegiance to any foreign country. Anyone who comes here illegally has legal allegiance to the country they came from. They aren’t asked to sign a petition to revoke the allegiance of the country they came from when they arrive here. You aren’t required to do that until you sign a petition for naturalization. My grandfather had to swear on that petition, that he gave up any and all allegiance to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. Any pregnant woman who comes here still has legal allegiance to the country she came from, along with the baby she carries, and they still have allegiance to the country they came from even after that child is born, because neither of them have signed away their allegiance to the country they came from.

So the precedent does not apply. Those here illegally are transients, not residents, and are not subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S. Their legal rights flow from their home countries, not from the U.S.

Both ABC and CBS focused on what the Seattle judge said rather than what Trump focused on: “subject to the jurisdiction of”. The 1898 case focused on a Chinese immigrant with both parents being “legal residents” (though not U.S. citizens). I think Trump is focusing on immigrants where both parents are neither U.S. citizens nor legal residents at the time of birth. I wouldn’t call the left winning this in a slam dunk but Trump has a chance.

No one voted for the judges. The judiciary depends upon the respect of the two other co-equal branches for its authority. Most importantly, all three branches answer to the people.

The people made their will clear last November 5.

An important practical consideration is the problem of “anchor babies”: their parents by law can be deported. This is incontrovertible. Children born here of parents here illegally remain citizens of their parents’ country.

The Wong Kim Ark case specifically addressed the citizenship status of children born in the United States to parents who were legal residents but not citizens.The late 19th century Supreme Court's decision confirmed that these children were indeed U.S. citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the case did not directly address the situation of children born to parents who are in the country illegally.

The specific question before the court was:

The question presented by this appeal may be thus stated: Is a person born within the United States of alien parents domiciled therein a citizen thereof by the fact of his birth?

See from the Brief for the appellant United States:

In the Supreme Court of the United States, October Term, 1895The United States, Appellant,

v.

Wong Kim Ark, Respondent.BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANT, THE CASE.

This is an appeal from the district court of the United States for the northern district of California, and is taken from the judgment of that court, discharging the respondent on habeas corpus cum causa from the custody of the collector of port of San Francisco, who refused to permit the respondent to land in the United States for the reason that he is a Chinese laborer and within the inhibitory provisions of the Chinese exclusion act. The respondent claimed exemption from that act upon the ground that he was born within the United States, and thereby because ipso facto a citizen thereof. The Government, while conceding the fact of birth, denied the conclusion of citizenship in that respect, contending that as the respondent was born of alien parents, to wit, subjects of the Emperor of China, he was at birth a subject of China, claimed by that nation to be such, and therefore was not when born "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States within the meaning and intent of the Constitution.

The district court, following as being stare decisis the ruling of Mr. Justice Field in the case of Look Tin Sing (10 Sawyer, 358), sustained the claim of the respondent, held him to be a citizen by birth, and permitted him to land. The question presented by this appeal may be thus stated: Is a person born within the United States of alien parents domiciled therein a citizen thereof by the fact of his birth? The appellant maintains the negative, and in that behalf assigns as error the ruling of the district court that the respondent is a natural-born citizen, and on that ground holding him exempt from the provisions of the Chinese exclusion act and permitting him to land.

[...]

At 39:

To hold that Wong Kim Ark is a natural-born citizen within the ruling now quoted, is to ignore the fact that at his birth he became a subject of China by reason of the allegiance of his parents to the Chinese Emperor. That fact is not open to controversy, for the law of China demonstrates its existence. He was therefore born subject to a foreign power; and although born subject to the laws of the United States, in the sense of being entitled to and receiving protection while within the territorial limits of the nation — a right of all aliens — yet he was not born subject to the "political jurisdiction" thereof, and for that reason is not a citizen. The judgment and order appealed from should be reversed, and the respondent remanded to the custody of the collector.

Respectfully submitted.

George D. Collins, Of Counsel for Appellant.

Holmes Conrad, Solicitor-General.

That argument requires a finding that all the nations of the world recognizing jus soli got it wrong for centuries.

The common law origin of jus soli begins with the case of Elyas de Rababyn (1290) II Rotuli Parliamentorum 139 where it was assumed that all persons born on English soil were subjects of the King.

It is far better known in common law from the Case of the Postnati, or Calvin v. Smith, 77 Eng. Rep. 377 (K.B. 1608).

In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 Fed. 382, 386 (1896); Opinion of the Court

The fourteenth amendment to the constitution of the United States must be controlling upon the question presented for decision in this matter, irrespective of what the common-law or international doctrine is. But the interpretation thereof is undoubtedly confused and complicated by the existence of these two doctrines, in view of the ambiguous and uncertain meaning of the qualifying phrase, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” which renders it a debatable question as to which rule the provision was intended to declare. Whatever of doubt there may be is with respect to the interpretation of that phrase. Does it mean “subject to the laws of the United States,” comprehending, in this expression, the allegiance that aliens owe in a foreign country to obey its laws; or does it signify, “to be subject to the political jurisdiction of the United States,” in the sense that is contended for on the part of the government? This question was ably and thoroughly considered in Re Look Tin Sing, supra, where it was held that it meant subject to the laws of the United States.

The Wong Kim Ark case specifically addressed the citizenship status of children born in the United States to parents who were legal residents but not citizens.

The specific question before the court was:

The question presented by this appeal may be thus stated: Is a person born within the United States of alien parents domiciled therein a citizen thereof by the fact of his birth?

See from the Brief for the appellant United States:

In the Supreme Court of the United States, October Term, 1895The United States, Appellant,

v.

Wong Kim Ark, Respondent.BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANT, THE CASE.

This is an appeal from the district court of the United States for the northern district of California, and is taken from the judgment of that court, discharging the respondent on habeas corpus cum causa from the custody of the collector of port of San Francisco, who refused to permit the respondent to land in the United States for the reason that he is a Chinese laborer and within the inhibitory provisions of the Chinese exclusion act. The respondent claimed exemption from that act upon the ground that he was born within the United States, and thereby because ipso facto a citizen thereof. The Government, while conceding the fact of birth, denied the conclusion of citizenship in that respect, contending that as the respondent was born of alien parents, to wit, subjects of the Emperor of China, he was at birth a subject of China, claimed by that nation to be such, and therefore was not when born "subject to the jurisdiction" of the United States within the meaning and intent of the Constitution.

The district court, following as being stare decisis the ruling of Mr. Justice Field in the case of Look Tin Sing (10 Sawyer, 358), sustained the claim of the respondent, held him to be a citizen by birth, and permitted him to land. The question presented by this appeal may be thus stated: Is a person born within the United States of alien parents domiciled therein a citizen thereof by the fact of his birth? The appellant maintains the negative, and in that behalf assigns as error the ruling of the district court that the respondent is a natural-born citizen, and on that ground holding him exempt from the provisions of the Chinese exclusion act and permitting him to land.

[...]

At 39:

To hold that Wong Kim Ark is a natural-born citizen within the ruling now quoted, is to ignore the fact that at his birth he became a subject of China by reason of the allegiance of his parents to the Chinese Emperor. That fact is not open to controversy, for the law of China demonstrates its existence. He was therefore born subject to a foreign power; and although born subject to the laws of the United States, in the sense of being entitled to and receiving protection while within the territorial limits of the nation — a right of all aliens — yet he was not born subject to the "political jurisdiction" thereof, and for that reason is not a citizen. The judgment and order appealed from should be reversed, and the respondent remanded to the custody of the collector.

Respectfully submitted.

George D. Collins, Of Counsel for Appellant.

Holmes Conrad, Solicitor-General.

That argument requires a finding that all the nations of the world recognizing jus soli got it wrong for centuries.

The common law origin of jus soli begins with the case of Elyas de Rababyn (1290) II Rotuli Parliamentorum 139 where it was assumed that all persons born on English soil were subjects of the King.

It is far better known in common law from the Case of the Postnati, or Calvin v. Smith, 77 Eng. Rep. 377 (K.B. 1608).

In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 Fed. 382, 386 (1896); Opinion of the Court

The fourteenth amendment to the constitution of the United States must be controlling upon the question presented for decision in this matter, irrespective of what the common-law or international doctrine is. But the interpretation thereof is undoubtedly confused and complicated by the existence of these two doctrines, in view of the ambiguous and uncertain meaning of the qualifying phrase, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” which renders it a debatable question as to which rule the provision was intended to declare. Whatever of doubt there may be is with respect to the interpretation of that phrase. Does it mean “subject to the laws of the United States,” comprehending, in this expression, the allegiance that aliens owe in a foreign country to obey its laws; or does it signify, “to be subject to the political jurisdiction of the United States,” in the sense that is contended for on the part of the government? This question was ably and thoroughly considered in Re Look Tin Sing, supra, where it was held that it meant subject to the laws of the United States.

This will not, of course, include persons [wp - CHILDREN] born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States, but will include every other class of persons."

It does not include CHILDREN born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States.

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36, 73 (1872)

The first observation we have to make on this clause is that it puts at rest both the questions which we stated to have been the subject of differences of opinion. It declares that persons may be citizens of the United States without regard to their citizenship of a particular State, and it overturns the Dred Scott decision by making all persons born within the United States and subject to its jurisdiction citizens of the United States. That its main purpose was to establish the citizenship of the negro can admit of no doubt. The phrase, "subject to its jurisdiction" was intended to exclude from its operation children of ministers, consuls, and citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States.

Yes but WHY? They should NOT have used "jus soli"

historical tradition across the world, including the United States, has been "jus sanguinis - "right of the blood" or "right of the father." A child followed the nationhood/classification of their father/group/relations. Thus they were subject to the "jurisdiction thereof."

Besides USA and Canada, NO major countries (except for Caribbean tax shelter nations) follow "jus soli" or birthright citizenship, even to this day.

That certainly never in the mind of the writers of the 14 Amendment.

Another issue is the ability of any federal judge to impose nationwide decisions.

If Trump can manage to get another judge to go the other way, then he can order the first judge to be ignored, and set up for a decision as to how much actual power these judges have.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.