Skip to comments.

US Civil War reading Recommendations?

Free Republic ^

| 11/23/2016

| Loud Mime

Posted on 11/23/2016 6:01:04 PM PST by Loud Mime

I am studying our Civil War; anybody have any recommendations for reading?

TOPICS: Reference

KEYWORDS: bookreview; books; civilwar; dixie; freeperbookclub; readinglist; ushistory

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 621-640, 641-660, 661-680 ... 721-729 next last

To: x

Your comment on Colwell: "He was against absolute 'free trade' -- not against free markets."

You can see here on page 22 that in discussion of the advent of free trade, that he does not make the argument you evoke. here

He did go on to say on page 57 that "Slavery is a great institution."

He must have been refuting Kettell?

To: PeaRidge

I see that you shamelessly quote the line "Slavery is a great institution" out of context. That's not a value judgement, as is revealed by the next sentence:

It concerns in this country, the interests of four millions of people, who, from the necessity of the case, can have no voice in determining their own condition.

The sentence refers to the overwhelming significance of slavery to the country. It's a big, domineering thing that's hard to get around or get rid of. He isn't using the word in its more common modern sense: "Slavery -- it's great!"

Colwell favored protective tariffs. In that sense he opposed "free trade." But he could appreciate that free trade could benefits some areas and industries (and hurt others). So it's not surprising that he might pay tribute to how well the planters had made use of free trade to enrich themselves. That didn't mean that he was in favor of the policy -- he saw that not everyone benefited from free trade -- or that he was disparaging market economies.

On page 22-23, I do find this:

The idea now pretty extensively entertained in the South, that New York is fattening on Southern trade and business is an utter delusion: New York is not piling up "Northern profits on Southern wealth." It is a misconception, which no unprejudiced man can entertain, if he will take the trouble to examine.

That is what Colwell set out to refute and what he largely does refute.

I might have given the impression that Colwell was more opposed to slavery than he was. Colwell wasn't an abolitionist but he did have serious disagreements with the slaveowner's great friend, Thomas Kettell, about the interpretation of statistics and the policy implications that should be drawn from the numbers.

Nineteenth century people don't pass our standards of political decency, but that doesn't mean that they didn't have bitter conflicts and arguments about many different matters. Colwell set out to refute Kettell's economic fallacies and certainly does some damage to Kettell's specious argument.

642

posted on

12/08/2016 3:10:18 PM PST

by

x

To: BroJoeK

If you were running shipping lines between the US and Europe wouldn't it make more sense to ship European products to an East Coast port, and then transship to a Gulf Coast port?

I can't see getting the goods to New Orleans and then having to backtrack to Eastern ports. Or taking goods from the East Coast to New Orleans to send off across the Atlantic.

There were perfectly logical reasons why New Orleans or Mobile or Galveston couldn't fully compete with ports on the Atlantic. The population centers were still in the East, so shipping would be heaviest between East Coast ports and Europe.

Why it was New York that came out on top, rather than Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, or Norfolk is another question, but in the 19th century geography stacked the deck against the Gulf ports.

643

posted on

12/08/2016 3:18:22 PM PST

by

x

To: PeaRidge; x; rockrr; DiogenesLamp

PeaRidge quoting:

"The act directed the secretary of the navy to accept on the part of the Government certain proposals that had been made for the carriage of the United States mails to foreign ports in American-built and American-owned steamships.

These proposals had been submitted to the postmaster-general (March 6, 1846) by Edward K. Collins and associates (James Brown and Stewart Brown) of New York, and A.G. Sloo of Cincinnati: one for mail transportation by steamship between New York and Liverpool, semimonthly, the other between New York and New Orleans, Havana, and Chagres, twice a month." Several points should be noted here:

- Even today some civilian equipment is built to military specifications with the idea that it could be called on in time of war or emergency.

And example is civilian air-liners specially reinforced to carry combat troops & equipment.

- Collins is mentioned here, and the Collins Line went bankrupt in 1857 despite government subsidies.

So even subsidies did not guarantee success.

- That Sloo was from Cincinnati tells us: "New York business interests" did not, after all, control everything.

Another PeaRidge post mentions a Charleston Line, which he says was actually New York owned, but must have had major Charleston interests in it to carry such a name.

- Most important we should note these government subsidies effected only a handful of "hi-tech" (for the time) high-speed mail carriers having nothing to do with hundreds & hundreds of every-day working ships required to move America's products along rivers, inland waterways and out to trans-oceanic ports.

So PeaRidge's claim that subsidies provided Northerners with monopolistic powers they used to extract 40% of slave-grown cotton revenues just doesn't stand up to closer examinations.

PeaRidge quoting: "The amounts received were sufficient to underwrite the costs of constructing multiple vessels.

Congress required that these ships meet military specifications and be available to the Navy in time of war.

The government was financing the growth of this business."

Which totaled up to maybe 1% of all the shipping used by US citizens at the time, and in any case was not restricted to New Yorkers.

644

posted on

12/09/2016 6:24:06 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: x

I enjoy being “shameless” when quoting an abolitionist who wraps himself in dialectic misdirection.

Here are a few more of Colwell’s quotes from his pamphlet that I “cherry picked” for you.

From pg 51:

“We regard African slavery as it now exists in the South, as justifiable on sound social, humane, and Christian considerations.”

From pg. 55:

It is quite certain that slavery in the South is not understood and appreciated in the North or in Europe as it should be...

“...an institution which so much concerns the interests and well being of human beings...deserves to be studied.

“...slavery deserves a social code of is own”

“...there are many large slaveholders in the South.....that if brought together for conference...might produce a constitution for slaves....after such a measure...abolitionism could no longer exist.”

I do not see or hear any rebuttal to Kettell’s economic study in any of that from his pamphlet.

To: x; PeaRidge; rockrr; DiogenesLamp

x quoting Colwell:

"The idea now pretty extensively entertained in the South, that New York is fattening on Southern trade and business is an utter delusion: New York is not piling up 'Northern profits on Southern wealth.'

It is a misconception, which no unprejudiced man can entertain, if he will take the trouble to examine." I'm having trouble following the discussion, but this quote does help.

If I understand: Kettell proposed Northerners were, in effect, stealing Southern wealth and Colwell tried to rebut that, right?

Googling Kettell & Colwell produces limited data, though it appears both publications are still available, for about $20 each.

I'll probably skip them...

Bottom line is, I'm not inclined to believe that Southern slave-masters were in any way being "ripped off" by Northern shippers & business interests, certainly in no way comparable to the degree of rip-off of slaves themselves!

But I would possibly concede that highly effective anti-North propaganda made Southerners feeeeeeeeel "ripped-off".

646

posted on

12/09/2016 7:02:24 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: x

x:

"I can't see getting the goods to New Orleans and then having to backtrack to Eastern ports.

Or taking goods from the East Coast to New Orleans to send off across the Atlantic."I have posted this link often before, because it opens a window on 1850s era New Orleans.

Among other things it reports that half the US cotton crop shipped from New Orleans.

Think about that.

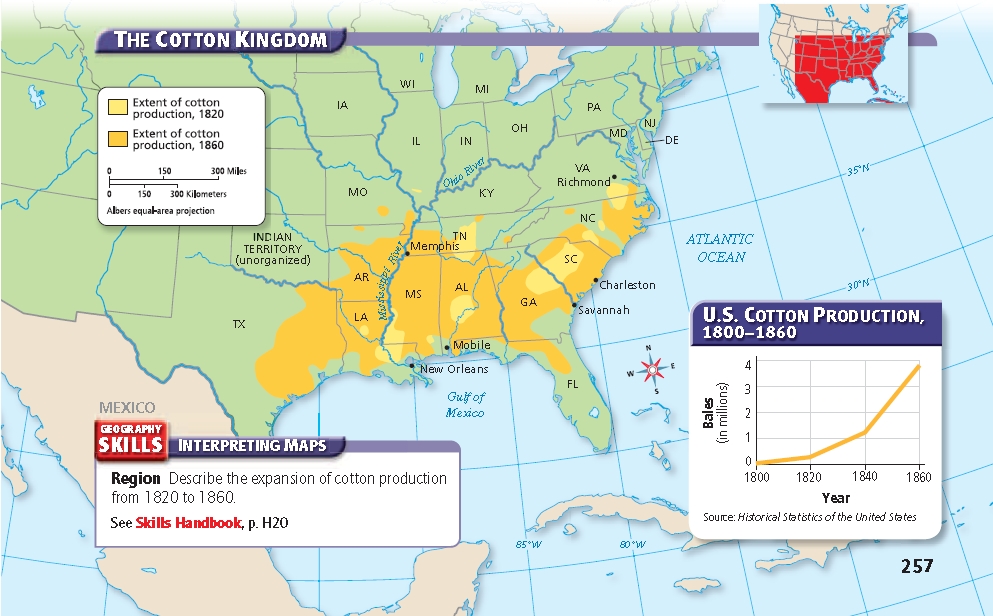

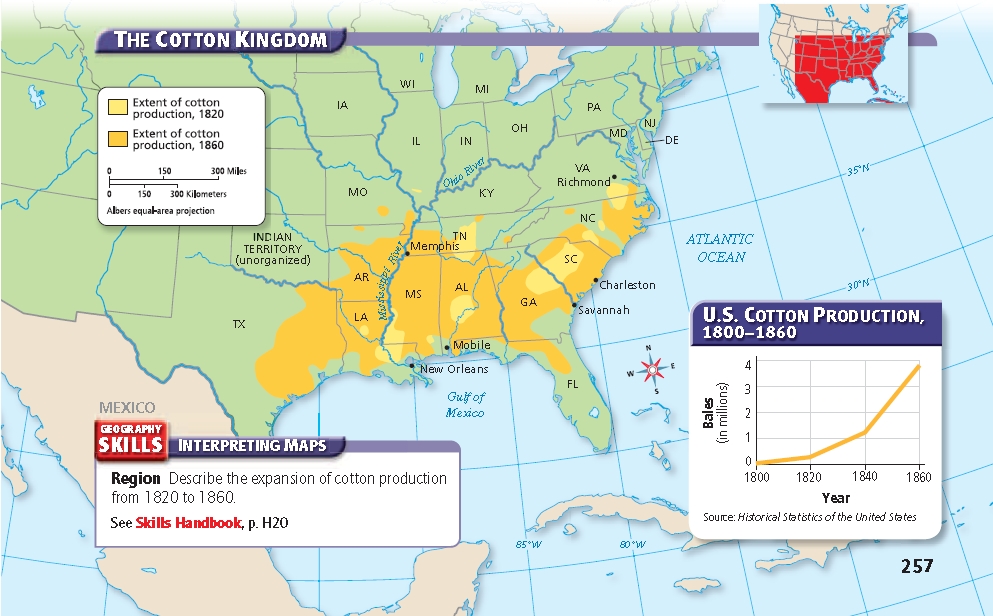

Now look at a map of cotton growing regions and you'll see that maybe 80% of US cotton was grown in places where Gulf Coast ports were the closest -- from Galveston to Mobile & Pensacola.

Point is: it would take hundreds of 1850s era ships to transport all that cotton from Gulf Coast ports to Europe (85%) and Northern US (15%) customers.

There's no reason to suppose such ships would stop in New York outbound, but might well deliver their inbound cargoes and immigrant passengers to New York rather than, say, New Orleans or Galveston.

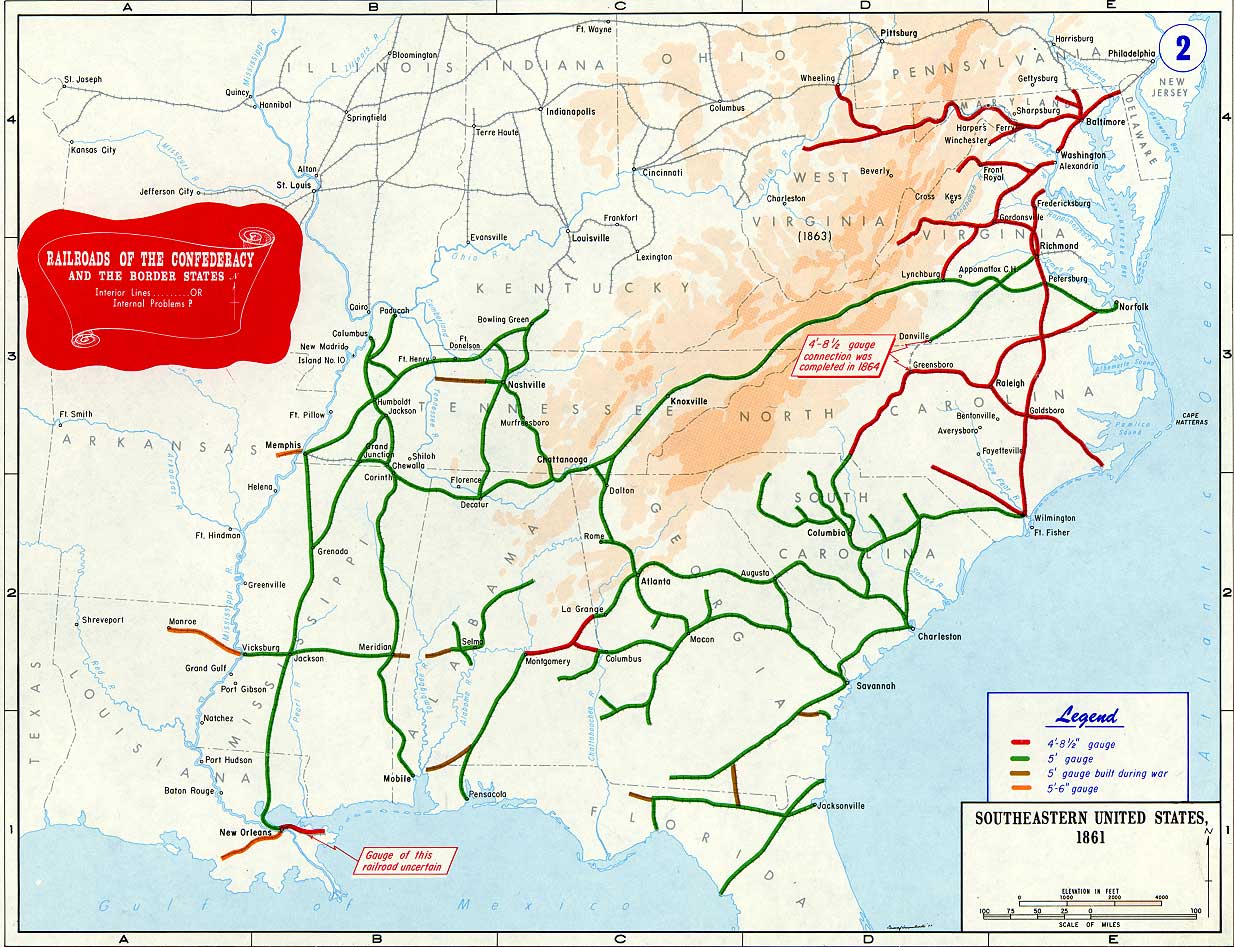

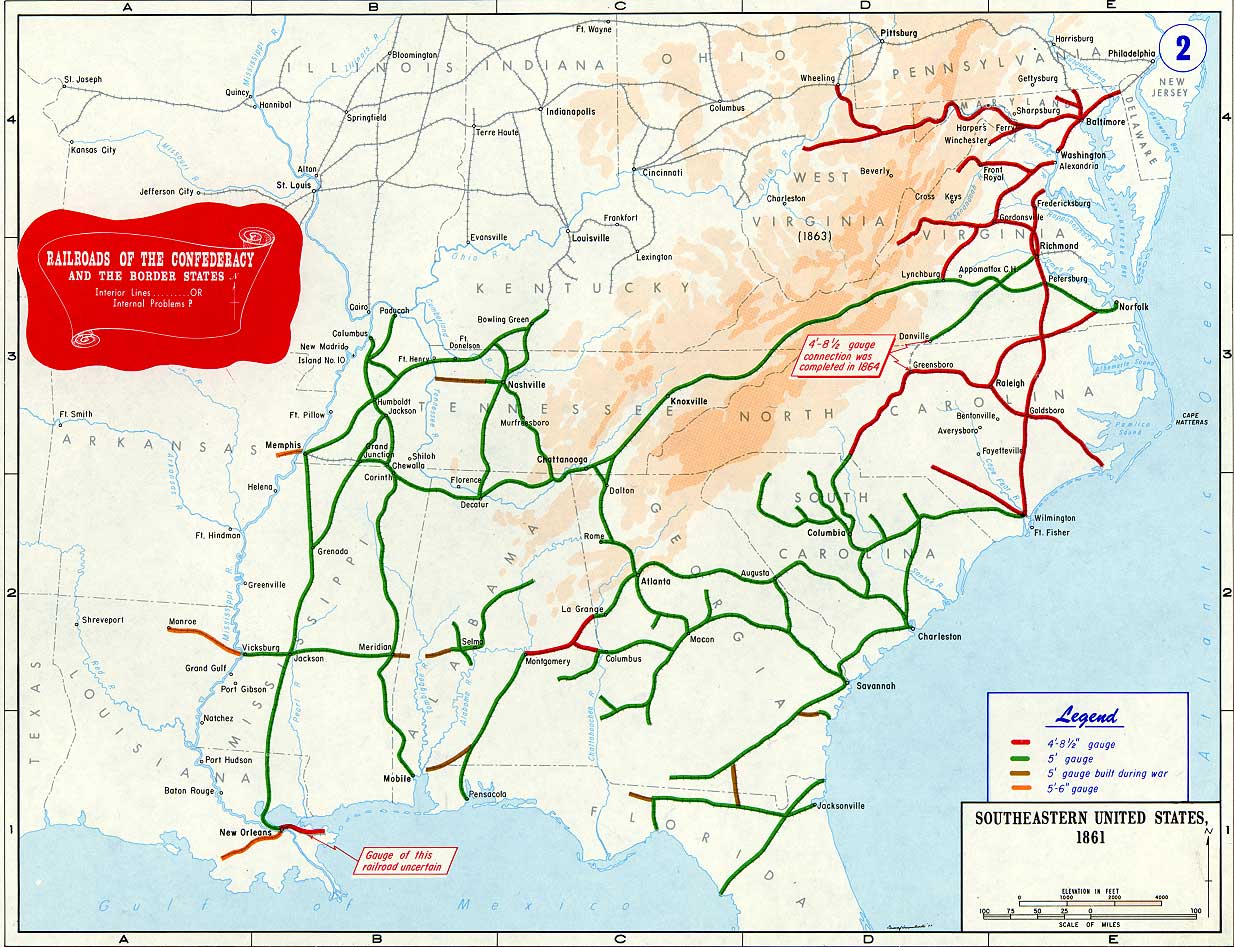

Note 1860 Southern railroads:

647

posted on

12/09/2016 8:03:18 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

To: BroJoeK

Kettell proposed Northerners were, in effect, stealing Southern wealth and Colwell tried to rebut that, right?

Yes. That is what they were arguing about.

Googling Kettell & Colwell produces limited data, though it appears both publications are still available, for about $20 each.

You can view them for free online:

Southern Wealth and Northern Profits

Southern Wealth and Northern Profits

Southern Wealth and Northern Profits

The Five Cotton States and New York

The Five Cotton States and New York

Bottom line is, I'm not inclined to believe that Southern slave-masters were in any way being "ripped off" by Northern shippers & business interests, certainly in no way comparable to the degree of rip-off of slaves themselves!

I agree. There was less realization of that at the time, but people weren't entirely unaware of what was going on. On top of that, Kettell, a New York City financial journalist drastically undervalued the services that his city and region provided to the cotton planters. Apparently, he was a Democrat and at the time that meant catering to Southern slaveholding interests and telling them what they wanted to hear.

648

posted on

12/09/2016 1:20:11 PM PST

by

x

To: PeaRidge

So you shamelessly pass over the economic part of an economic article and then complain that what you do cite doesn't give you an economic refutation of Kettell's pamphlet.

I am not an economist either, but I know that you can't simply ignore the analytical parts of a book and then claim that it offers no analysis.

In a nutshell, Colwell argued:

The Five Cotton States are large importers of Northern commodities, many of which are made expressly for them; in payment for these, and for advances on cotton, they give not their surplus of cotton, but the chief part of their cotton, either in kind, or in Bills of Exchange drawn upon it, or Bills of Lading transferring the ownership of it.

Whether or not he proves that decisively, I can't tell, but he does bring forth information to support his contentions. If his statistics are less comprehensive than Kettell's, nonetheless he does offer analysis and argument and doesn't try to overwhelm the reader with reams of data of dubious relevance.

You are also shameless in ignoring the situation in 1860. Slavery was a fact. It had passionate defenders. It wasn't going away any time soon. Abolitionism was a crime in many states and a scandal to the rest of the country.

Anyone making an appeal to slaveowners or supporters of slavery or those who were neutral would have to accept the fact of slavery and indulge in some flattery or risk being condemned as an abolitionist.

Abolitionist literature was banned -- and often burned. That was the fate of Hinton Rowan Helper's The Impending Crisis of the South, a book which tried to make a very pro-Southern argument against slavery which was quickly banned, vilified, and burned.

I'm not saying Colwell was a secret abolitionist, just that -- given the circumstances -- you can't blame him for making flattering appeals to people who weren't outraged by slavery.

We hear over and over again that one can't judge 19th century figures by 20th or 21st century standards, yet here you are doing just exactly that.

649

posted on

12/09/2016 1:43:28 PM PST

by

x

To: All

There was some question about the ownership of The Charleston Line. It was founded by Anson Phelpsz, industrialist and philanthropist.

Born March 24, 1781 in Simsbury, Connecticut. Died November 30, 1853 (aged 72) New York City, New York

Known for Founder Phelps Dodge Mining Corporation. Beginning with a saddlery business, he founded Phelps, Dodge & Co. in 1833 as an export-import steam shipping business with his sons-in-laws William E. Dodge and Daniel James based as partners in Liverpool, England. His third son-in-law, James Boulter Stokes, became a partner some years later. He founded the Charleston Line.

Later in the 19th century after the senior Phelps’ death, Phelps Dodge acquired mining interests and companies in the American West, and became known primarily as a mining company.

To continue the issue of the growth of the shipping subsidy and steam ship development: (again from Bacon)

“All the contracts thus provided for were concluded the same year. Each was to run for ten years. The first executed was that with Mr. Sloo. It called for five steamships of not less than 1500 tons, and a semi-monthly service. The line was to touch at Charleston, if practicable, and at Savannah. The ships were to have engines by direct action; and each ship was to be sheathed with copper.

“The subsidy was fixed at two hundred and ninety thousand dollars a year, a rate of $1.83-1/2 per mile, the distance to be sailed out and back being 158,000 miles. Mr. Sloo immediately set over his contract to George Law, Marshall O. Roberts, and Bowes McIlvaine, of New York. The second contract was for the Pacific service, connecting with the mail by the Sloo line across the Isthmus. This was made with Arnold Harris of Arkansas. It provided for a monthly service between Panama and Astoria, Oregon, calling at San Diego, Monterey, and San Francisco, with a subsidy of one hundred and ninety-nine thousand dollars per annum.

“Three steamers were to be furnished, two of not less than a thousand tons each. Upon receiving the contract Mr. Harris immediately transferred it to W.H. Aspinwall of New York, representing the newly formed Pacific Mail Steamship Company.

“The third was the Collins contract. This stipulated for a semi-monthly service between New York and Liverpool during the eight open months of the year, and a monthly service through the four winter months, with five steamers, each of not less than 2000 tons and engines of a thousand horsepower. The first ship was to be ready for service in eighteen months after the date of the contract, November 1, 1847. The subsidy was fixed at $19,250 per twenty round trips, or three hundred and eighty-five thousand dollars a year, a rate of $3.11 a mile for sailing about 124,000 miles.

“By subsequent acts the secretary of the navy was authorized to advance twenty-five thousand dollars a month on each of the ships called for by these several contracts from the time of their launching to their finish; and the date of the completion of the first Collins steamer and the opening of the New York and Liverpool service was extended to June 1, 1850.

“At the same time that the secretary of the navy was executing these contracts the postmaster-general under the authority of an act “to establish certain Post Routes and for other purposes,” also approved March 3, 1847, was contracting for a steamship mail-service between Charleston and Havana, with a subsidy of forty-five thousand dollars per annum. This contract was entered into with M.C. Mordecai of Charleston, who agreed to furnish steamships suitable for war purposes, and to perform a monthly service. Several other propositions for steamship service to various foreign countries were made to the postmaster-general at this time, but none was accepted.

The pioneer Bremen-Havre line began its service on the first day of June 1847, with two steamers. These were the Washington and the Hermann, built in New York, strong and large, of 1640 tons and 1734 tons, respectively, side-wheelers, bark-rigged. At first they made the run to Bremen in from twelve to seventeen days, much better time than the average clipper. But up to 1851 they had no regular schedule of sailings, and, their speed being unsatisfactory, few mails were sent by them. The subsidy payments, therefore, were made for each voyage separately.

“They had also ceased to command the patronage of travellers. Nevertheless, as a committee of the Senate in 1850 reported, they were believed to have been “profitable to their owners as freight vessels, and of essential service in promoting the interests of American commerce.” The full service, with twelve trips to Bremen and twelve to Havre, was finally begun in 1851, when two more, and larger ships,—the Franklin and the Humboldt, each of 2184 tons, were added to the Havre line.

To: DiogenesLamp

651

posted on

12/11/2016 4:18:29 PM PST

by

southland

( I have faith in the creator Republicans freed the slaves. Isa.54: 17 , Deplorable...)

To: southland

Bookmark I didn't realize the significance of that map when I first saw it. It wasn't until later when people informed me that nearly 3/4ths of the earned export value of the USA came from the Southern States. As soon as I realized that the Southern states were making all the money, yet the money was ending up in New York that I realized there was a much bigger picture here than what I was taught when growing up.

I have since filled in additional details. Not only was the North going to lose huge sums of money if the South became independent, but the South would have subsequently built competing industries to the North, and eventually brought all the Midwestern states within it's sphere of influence.

It would have eventually became the larger and more powerful of the two sections of what used to be the USA. The only way the North could stop this was to stop Southern independence, and for that they needed a war.

652

posted on

12/12/2016 6:34:16 AM PST

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: x; rustbucket; DiogenesLamp; central_va

According to your post, I ‘shamelessly’ pass over Colwell’s economic ‘part’.....of course I did and I pointed out his quote where he says he exaggerated the census data by 50% based on undocumented ‘officials’ opinions.

I rather be shameless than advocate the ramblings of someone, who if alive, would be a guest on “Coast to Coast”.

To: PeaRidge

Kettell makes use of estimates as well. It would have been hard not to. The census comes once every ten years, so estimates of current values are unavoidable if you want to be up to date.

Colwell made an estimate based on the available census data and with reference to state data. Even if his estimate was wrong -- off by half, if you like -- his basic point, that the states surrounding New York contributed more to its economy than the Deep South cotton states -- holds up, and you can see that in his figures.

Kettell's approach was based on the idea that you could trace all wealth back to agriculture or natural resources. He left out the value added by manufactures and services. It's not hard to see where he went wrong. Plenty of resource-rich countries have failed to develop because they failed to diversify and remained tied to a single crop or commodity.

654

posted on

12/12/2016 3:07:21 PM PST

by

x

To: x

Compared to the books you recommended earlier on this thread, Colwell’s pamphlet is a comic book. Why you continue to defend this misrepresentation can only be explained by a need to avoid exposure as a polemic.

To: PeaRidge; BroJoeK

That's not a fair comparison. Given a century and a half of research and reflection one could come up with a lot of insights. When one has to act in the moment, bring together such sources as they are, reach conclusions, and communicate them to a public that may be indifferent or hostile, what one comes up with is bound to look weaker than what a historian a century and a half later could make.

The bottom line here is that there was much hack writing and speechifying in the years leading up to the Civil War arguing that cotton was king, that the slave states were being exploited by the free North and that an independent cotton confederacy would be a good thing. Colwell took up the challenge and wrote a response to some very dangerous ideas -- ideas which you shamelessly circulate even a century later, when we all know how harmful they were. How can one not commend him for that?

If you're still looking for a refutation of Kettell's pernicious book, try Samuel Powell's Notes on Southern Wealth and Northern Profits. Like Colwell's book, it's short. It's not an exhaustive treatment of the subject. Both books were written under the pressure of events to make a point that needed making. There is nothing wrong with that.

656

posted on

12/13/2016 1:49:54 PM PST

by

x

To: x

Like I said: “Why you continue to defend this misrepresentation can only be explained by a need to avoid exposure as a polemic.”

Maybe more than one.

To: PeaRidge; BroJoeK; rockrr

Like I said: “Why you continue to defend this misrepresentation can only be explained by a need to avoid exposure as a polemic.”

*Shudder*

I just dread being exposed as "a polemic"! My deepest and darkest secret!

Seriously, you're just repeating the same nonsense and once again exposing yourself as what you are.

658

posted on

12/13/2016 2:33:16 PM PST

by

x

To: x

Of course I was speaking of Colwell and Powell.

How quickly you feel insulted.

To: x; PeaRidge; rockrr; DiogenesLamp

x:

"If you're still looking for a refutation of Kettell's pernicious book, try Samuel Powell's Notes on Southern Wealth and Northern Profits.

Like Colwell's book, it's short." Thanks for the references, x, I read good parts of Colwell's book.

Colwell makes some of the same arguments I have posted here.

For example, he demonstrates with actual numbers that while more than half of US cotton shipped from New Orleans and about 75% from Gulf Coast ports, less than 10% shipped to Europe from New York City.

But it is very dense reading, and not all of it of interest to us today.

It reminds me why I'm a "history buff", not a history scholar, since I much prefer the abbreviated Cliff Notes. ;-)

For example, here's a summary which includes some of Kettell's arguments with realistic reporting on what was actually going on.

![]()

"As one Alabama polemicist wrote at the end of the 1840s, 'our slaves are clothed with Northern manufactured goods, have Northern hats and shoes, work with Northern hoes, ploughs, and other implements, are chastised with Northern made whips, and are working for Northern more than Southern profit.'... "Kettell’s analysis in turn gave Southern politicians confidence that the North, if only from the standpoint of self-interest, would eventually accede to new constitutional protections for slaveholding.

"No group supported such compromises more than the merchants and bankers of New York City.

The early months of 1861 brought unprecedented volatility to the city’s financial markets, with stocks rising and falling on rumors swirling around Virginia’s secession debate.

A delegation of 30 New York businessmen traveled to Washington at the end of January with a petition for compromise with the signatures of some 40,000 merchants, clerks and scriveners.

"At the Congressional peace talks that February, William E. Dodge spoke 'as a plain merchant' sent at the urging of the New York Chamber of Commerce.

'I am a business man, and I take a business view of this subject,' Dodge said.

From his point of view, 'the whole country is upon the eve of such a financial crisis as it has never seen.'

Dodge had voted for Lincoln, but actively supported constitutional amendments to protect slavery.

Told that New Englanders would never brook such overt protection for slavery, he scoffed: 'they are true Yankees; they know how to get the dollars and how to hold on to them when they have got them.'

"Many voices echoed Dodge’s claim that self-interest would prevent the outbreak of violence.

As a New York group calling itself the American Society for Promoting National Unity pointed out, a war might serve the needs of politicians and agitators in both sections, but it would jeopardize the prospects of businessmen everywhere.

Writing in the New York Times, businessman Daniel Lord contended that South Carolinians would not 'any more than Yankeedom, refuse a good bargain because driven with parties of different politics.'

In turn, William Gregg, one of the South’s leading manufacturers, predicted that war 'will be death to every branch of business.'

A few days after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Gregg wrote to a Massachusetts associate, 'I trust that you business men of the North will see the necessity of putting a stop to a war.'

"By that time, however, many of the same Northern business leaders who had earlier argued for concessions to the South now rallied to the Union cause.

Prominent merchants in New York, along with Mayor Fernando Wood, abandoned their own secessionist fantasies of a no-tariff 'free city' at the mouth of the Hudson and instead raised funds to mobilize the Union army.

Some realized that war was now the only way to bring the South back into the Union, and that to let the Confederacy go would have allowed Southerners to default on the $125 million they still owed New York firms.

"Others represented a new class of industrialists, men whose investments were not primarily linked to slavery and whose political demands on the federal government increasingly diverged from those of Southern slaveholders and their Northern allies.

They demanded higher tariffs, not free trade, and they hoped for the expansion of free labor agriculture in the West, not slave plantations.

"Of course, the dire predictions did not come to pass.

The northern economy did not collapse without access to Southern markets, a monopoly on cotton did not make the Confederacy invulnerable and economic self-interest did not forestall a bloody conflict.

Yet by reminding us of slavery’s importance to the nation as a whole, these prognostications suggest that the Civil War was hardly the result of the inherent hostility of capitalism to slavery.

The intertwining of those two economies over the previous decades yielded a Civil War more surprising and singular than our histories have yet recovered."

So, to the degree that DiogenesLamp and PeaRidge's assertions reflect this reporting, we have to concede it.

But I think they go far beyond historical facts into the realm of pro-Confederate mythology when they claim that Democrat New York businessmen were somehow in the driver's seat, forcing "Ape" Lincoln's Black Republicans to "start a war" when they would otherwise have compromised for peace.

In fact, Lincoln in 1861 was not focused on Democrat New York businessmen, but on his Oath of Office to preserve, protect and defend the US Constitution.

So, what DiogenesLamp & PeaRidge here post about is not Lincoln's motivation, but rather the question of why Democrat New York businessmen, erstwhile allies of the Southern Slave Power suddenly switched sides from demanding compromise to supporting military action against secessionists.

660

posted on

12/14/2016 4:55:04 AM PST

by

BroJoeK

(a little historical perspective...)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 621-640, 641-660, 661-680 ... 721-729 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson