Skip to comments.

The Boomer Mirage

Brownstone Institute ^

| August 13, 2025

| Josh Stylman

Posted on 08/14/2025 9:30:23 AM PDT by Heartlander

The Boomer Mirage

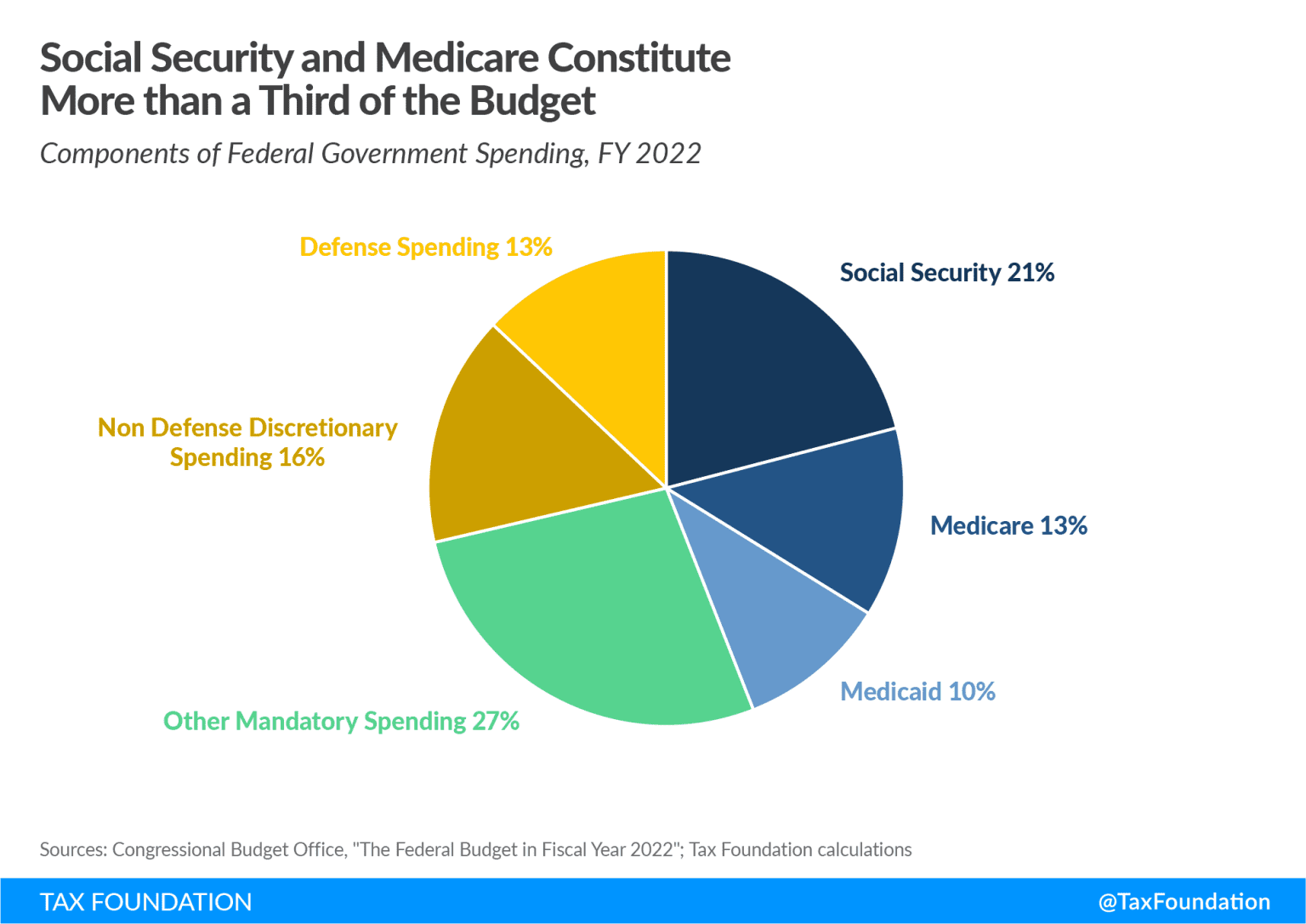

I saw this chart making the rounds on Twitter this week, and it stopped me cold. While the specific figures combine data from multiple sources, the trend is undeniable: in 1950, over half of 30-year-olds were married homeowners. By 2025, some analysts project that number as low as 13%.

That’s not a societal transformation. It’s not an economic fluke. It’s the visible outcome of an invisible strategy—one that extracted everything it could from a three-generation arc and left only illusions in its place.

They’ll tell you people just choose differently now—that marriage rates fell because of changing values. But people can’t choose what they can’t afford. When the economic foundation for family formation disappears, cultural changes follow inevitably. That chart doesn’t show us changing values or new priorities. It shows systemic breakdown, disguised for decades as freedom.

It maps the slow evaporation of the social contract. For one generation, adulthood was a starting point. For the next, a struggle. For the latest, an abstraction—marketed endlessly but almost never attained. What began as a rite of passage has become a paywalled simulation.

The post–World War II boom was never sustainable. In hindsight, this was obvious. It relied on conditions that were always time-limited: cheap energy from newly tapped oil fields, industrial monopolies before globalization kicked in, dollar hegemony that exported inflation globally, and a demographic pyramid with more workers than retirees. It was a golden window, not a golden age. And when the window closed, the illusion had to be maintained—through leverage, narrative, and ever-increasing sacrifice from the generations that followed.

The math quietly stopped working. Boomers bought homes for two or three times their annual income during an era when interest rates would fall for the next four decades—turning their mortgages into wealth-building machines as rates dropped from 15% to near-zero. Today’s buyers face five to six times their income—or more in major cities—while rates can only go up from historic lows. Where Boomers rode a 40-year tailwind of falling borrowing costs that inflated their assets while deflated their debt, current generations face headwinds at every turn. The Federal Reserve data confirms this unprecedented decline, showing rates falling from over 18% in the early 1980s to near 2.6% by 2021.

The housing market itself tells the story: recent data shows over 500,000 more sellers than buyers – not because homes are affordable, but because an entire generation has been systematically priced out.

The institutions that promised stability—education, government, media, finance—mutated into extraction machines. Still speaking the old language, they now served a different purpose: to keep people compliant inside a system that no longer offered a way out.

This wasn’t merely economic. It was existential. The foundations of meaning—family, ownership, stability—were quietly downgraded to lifestyle preferences, and then systematically priced out. People without homes are easier to relocate. People without families are easier to isolate. People without rootedness are easier to govern.

The Boomers didn’t design the con, but they lived in its payout phase. They received land, pensions, and a functional society. Many still believe they earned it, unable to recognize how thoroughly their reality was engineered from the start. Their children were left trying to replicate a model that no longer existed. Their grandchildren have grown up in the wreckage, wondering why their competence and effort never translate into traction.

This didn’t happen by accident. As I’ve documented in “The Technocratic Blueprint,” we’re witnessing the culmination of a century-long plan—a sophisticated pump-and-dump scheme where the bill is finally coming due. The architecture for this extraction has deep historical roots, dating back to systematic changes in how America was governed and how citizens were legally classified. What followed was a long, slow harvest of the population—one that disguised control as progress, debt as opportunity, and collapse as evolution. The postwar boom didn’t contradict that system—it lubricated it.

Now, the mirage is gone. What was once promised can no longer be afforded. The institutions that upheld the illusion are spent. They extract, but no longer inspire. They preach equity while enforcing dependence. They sell empowerment while removing agency.

And still, they insist the dream is alive.

But here’s where the extraction becomes truly sophisticated. As the traditional American Dream died, a new form of participation emerged: digital membership in what amounts to a global dollar club. As KFrecently explained in his analysis of the GENIUS Act, stablecoins—digital bank accounts disguised as innovation—have exploded to serve 400 million users globally while generating massive profits for their issuers.

The trade-off is stark. Boomers got real assets with relative transactional privacy. The next generation gets digital “assets”—stablecoin wallets, app-based banking, algorithmic financial services—in exchange for comprehensive surveillance. What looks like financial inclusion is actually the infrastructure for total economic monitoring.

This represents the systematic replacement of real value with declared value across every domain. America has become a “club promoter” for the global dollar system, offering relaxed entry requirements that have drawn hundreds of billions into US Treasury-backed stablecoins. Users get access to “dollar-denominated wealth” through stablecoins that pay them no interest while the issuers pocket billions from the Treasury yields. It’s the same extraction model that’s been systematically engineered through culture and media for decades, just scaled globally and digitized.

Experts in these systems, like Aaron Day, warn that this represents a “backdoor CBDC”—applying existing financial surveillance laws to what was previously private money.

The surveillance trade-off is particularly insidious. In the short term, these systems offer less monitoring than traditional banks—no extensive paperwork, minimal identity verification. But once everyone is locked into the digital infrastructure, America can impose far stricter controls than ever before. Every transaction becomes trackable, every account becomes freezable, every economic participant becomes manageable.

We’re witnessing the replacement of physical ownership with digital access—and calling it progress. Where Boomers built equity in homes, the next generation builds balances in accounts that can be monitored, modified, or eliminated with keystrokes.

But charts don’t lie. That one chart—the brutal slope from 52% to 13%—says what no institution will admit: the old system is dead. It wasn’t lost. It was liquidated—and we were the product.

What gets built in its place remains an open question. The GENIUS Act’s full-reserve model could enable either unprecedented control—or the first real challenge to fractional-reserve banking in a century. But as Catherine Austin Fitts has pointed out, the Act contains no protections against programmable money, potentially creating private CBDCs with even less oversight than government-issued digital currency.

As she explains, ‘the issuing is not centralized, it’s dispersed. But if you look at the control mechanism of a social credit system and we know the federal government is doing remarkable things to pull together all the data they need to do a social credit system controlled by private corporations, tech companies, essentially.’ The outcome isn’t predetermined—it’s being decided right now.

The good news is that once the spell breaks, you stop trying to win the rigged game. You stop competing for scraps and start building something real. Not a nostalgic replica of a world that’s gone—but a new structure, grounded in truth, agency, and actual sovereignty. The chart that documents the death of the old dream becomes the blueprint for something better—if we’re honest enough to read what it’s really telling us.

Republished from the author’s Substack

TOPICS: Business/Economy; Society

KEYWORDS:

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-48 next last

To: dfwgator

Yes, that’s true. When we watched MASH on tv, it seemed like it was a glimpse into Vietnam for some of us, but it was supposedly taking place during the Korean War. Vietnam was very present in my life growing up.

21

posted on

08/14/2025 11:16:31 AM PDT

by

FamiliarFace

(I got my own way of livin' But everything gets done With a southern accent Where I come from. TPetty)

To: FamiliarFace

We didn’t try to keep up with the Joneses. Compared to what young people face today with social media, I think it's fair to say... "we didn't even know who the Jones were". It's a brave new world.

I'm also a Late Boomer. I think we need a different category. OG 'Boomers' had a far different experience. I was married and 26 when I tried to by my first home. Mortgage rates were close to 20%! All I could afford was a 30+ yr old, frame home that was barely 1200 Ft2. For that, my house note was ~ $600 a month.

Meanwhile, my bosses were paying $400 a month for newer houses that were 3000+ Ft2, custom built, all brick... financed at rates as low as 3%. I certainly didn't feel any "privilege".

The article starts with an interesting chart. But I think he draws the wrong conclusions. LESS 30 yr old are married at all now.. far less. That lowers the pool of potentials.

The ones who are married, aren't yet earning enough to buy a home because prices have been driven up so much? Why? Mainly because of the lack of supply. Zoning restrictions, increasing regulation, and destruction of the purchasing power of our money. Decades of inflation have put younger people behind more than any because they lack real assets that protect one from inflation.

People will adapt. Younger kids today eat out less, drink less, buy used things more. They are adjusting their lifestyles to fit their actual situation. The BEST thing we could do for them is: STOP monetary devaluation.

To: FamiliarFace

I was just telling my kids this the other day: What the “kids” seem not to realize is the degree of competition for EVERYTHING in the boomer and Gen X groups. The schools were packed. Colleges were packed. The job market was stuffed to overflowing.

Yes, if you could get ahead of the pack, it was great. But for a kid born in 1960, it was like fighting for scraps my entire life.

Competition is a great thing. But you need to learn to compete.

To: ClearCase_guy

I don’t recall the 70s as being a picnic

To: Heartlander

“””” in 1950, over half of 30-year-olds were married homeowners. By 2025, some analysts project that number as low as 13%.””””

So what was it in 1980 to 1990 which would be the range for most boomers?

25

posted on

08/14/2025 1:04:28 PM PDT

by

ansel12

((NATO warrior under Reagan, and RA under Nixon, bemoaning the pro-Russians from Vietnam to Ukraine.))

To: FamiliarFace

About 10 million boomers served in the military.

26

posted on

08/14/2025 1:07:11 PM PDT

by

ansel12

((NATO warrior under Reagan, and RA under Nixon, bemoaning the pro-Russians from Vietnam to Ukraine.))

To: Heartlander

The architecture for this extraction has deep historical roots, dating back to systematic changes in how America was governed and how citizens were legally classified. What followed was a long, slow harvest of the population—one that disguised control as progress, debt as opportunity, and collapse as evolution. Couldn't the same thing be said about the "boomers" of the 1880s who thrived during Reconstruction, only to see their children have to adapt to the changes in goverment from the 1913 Constitutional amendments, followed by their grandchildren suffering through the Great Depression?

-PJ

27

posted on

08/14/2025 1:25:56 PM PDT

by

Political Junkie Too

( * LAAP = Left-wing Activist Agitprop Press (formerly known as the MSM))

To: Heartlander

In 1950, 36% of American homes lacked full plumbing, outhouses were common, which flies in the face of perceptions of 1950 America.

In 1950 the average family income was $3,300.

28

posted on

08/14/2025 1:27:37 PM PDT

by

ansel12

((NATO warrior under Reagan, and RA under Nixon, bemoaning the pro-Russians from Vietnam to Ukraine.))

To: Heartlander

in 1950, over half of 30-year-olds were married homeowners.My brother used to say, if you don't own a house by 30 you're a loser.

29

posted on

08/14/2025 1:29:55 PM PDT

by

1Old Pro

To: Heartlander

My first mortgage in the 1980s had a percentage rate in the teens. I think the upper teens.

30

posted on

08/14/2025 1:33:21 PM PDT

by

blueunicorn6

("A crack shot and a good dancer” )

To: FamiliarFace

There were more hours of MASH episodes than actual hours in the Korean war.

31

posted on

08/14/2025 1:49:29 PM PDT

by

GingisK

To: Vermont Lt

And 1950 home owners were NOT boomers The oldest possible "boomer" was 15 years old in 1960.

And generational stereotyping is for idiots.

BUT ...

The explosive growth of government enabled by income taxation and instigated by the fascist policies of Franklin Roosevelt is now clearly unsustainable.

32

posted on

08/14/2025 1:56:18 PM PDT

by

NorthMountain

(... the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed)

To: ansel12

$3300 in “1950 dollars” translates to $43,870.72 in “2025 dollars”.

33

posted on

08/14/2025 2:02:10 PM PDT

by

NorthMountain

(... the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed)

To: NorthMountain

“”””The oldest possible “boomer” was 15 years old in 1960.””””

That would be 14 wouldn’t it?

34

posted on

08/14/2025 2:02:53 PM PDT

by

ansel12

((NATO warrior under Reagan, and RA under Nixon, bemoaning the pro-Russians from Vietnam to Ukraine.))

To: Heartlander

35

posted on

08/14/2025 2:03:13 PM PDT

by

Albion Wilde

(If [mortals] are so wicked with religion, what would they be without it? —Benjamin Franklin)

To: ansel12

Last I looked, the people who think named “generations” mean something count the “baby boom” as starting in 1945. But I don’t really care ... If it started in 1946 then yes, 14 ... which just reinforces the point. What 30 year old people had in 1950 has nothing to do with so-called “boomers”. This article is largely crap.

36

posted on

08/14/2025 2:06:21 PM PDT

by

NorthMountain

(... the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed)

To: NorthMountain

What 30 year old people had in 1950 has nothing to do with so-called “boomers”. This article is largely crap. Yep. This is all about the Communist continuing to divide the united. Or should I say, the once united. They've done a remarkable job!

37

posted on

08/14/2025 2:40:31 PM PDT

by

dragnet2

(Diversion and evasion are tools of deceit)

To: Heartlander

...in 1950, over half of 30-year-olds were married homeowners.And, in my mind, the key word to the whole article is found in this phrase. And that key word is "married".

38

posted on

08/14/2025 2:54:36 PM PDT

by

BlueLancer

(Orchides Forum Trahite - Cordes Et Mentes Veniant)

To: GingisK

There were more hours of MASH episodes than actual hours in the Korean war.There were 251 episodes of MASH. Almost all were half-hour episodes. If you played them all, one right after another, they'd be finished in less than a week. The Korean War lasted more than three years.

To: HartleyMBaldwin

Ah, fine catch. The show went on for more years than the war lasted.

40

posted on

08/14/2025 4:49:10 PM PDT

by

GingisK

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-48 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson