Posted on 12/24/2005 1:43:14 AM PST by Swordmaker

PDF Version (Best for Printing & Page Reading)

By Daniel R. Porter (Updated October 28, 2005)

The primary skeptical argument, carbon 14 dating, had been eliminated. The

shroud might be 2000 years old, after all. But like Hydra, the Greek mythological beast,

controversy grew a weird new head.

With the Winter Olympics coming to Turin in February, 2006, bringing a million spectators and thousands of journalists, articles that describe this magnificent Italian city are becoming commonplace. Many journalists rightly feel that they should mention the city’s most famous artifact, the Shroud of Turin. And indeed they should. But what to write? Because the shroud is a religious object, believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus, and because scientists and historians have yet to prove or disprove its authenticity, it is controversial and interesting.

Until recently, skeptics had the upper hand in the ongoing debate about its authenticity. Carbon 14 dating in 1988 seemed to show that it was medieval. Researchers, who were not experts in radiocarbon dating, but nonetheless convinced the shroud was authentic, tried to explain why the scientific dating was incorrect. Often cited in the news media in an attempt at balanced reporting, these explanations – one was that a fire in 1532 changed the age of the cloth, another was that a bioplastic-polymer growing on the cloth contaminated the sample – lacked scientific credibility. Scientists, who were experts in radiocarbon dating, pooh-poohed these explanations.

It was not until 2005 that things changed. An article appeared in a peer-reviewed scientific journal Thermochimica Acta, which proved that the carbon 14 dating was flawed because the sample was invalid. Moreover, this article, by Raymond N. Rogers, a well-published chemist, and a Fellow of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, explained why the cloth was much older. It was at least twice as old as the radiocarbon date, and possibly 2000 years old.

Peer-reviewed scientific journals are important. It is the way scientists normally report scientific findings and theories. Articles submitted to such journals are carefully reviewed for adherence to scientific methods and the absence of speculation and polemics. Reviews are often anonymous. Facts are checked and formulas are examined. The review procedure sometimes takes months to complete, as it did for Rogers.

It was Nature, another prestigious peer-reviewed journal, that in 1989, reported that carbon 14 dating ‘proved’ the shroud was a hoax. Rogers found no fault with the article in Nature. Nor did he find fault with the quality of the carbon 14 dating. He defended it. What Rogers found was that the carbon 14 sample was taken from a mended area of the cloth that contained significant amounts of newer material. This was not the fault of the radiocarbon laboratories. But it did show that the dating was invalid.

Immediately after the publication of Rogers’ paper, Nature published a commentary by scientist-journalist Philip Ball. “Attempts to date the Turin Shroud are a great game,” he wrote, “but don't imagine that they will convince anyone . . . The scientific study of the Turin shroud is like a microcosm of the scientific search for God: it does more to inflame any debate than settle it.” Later in his commentary Ball added, “And yet, the shroud is a remarkable artefact, one of the few religious relics to have a justifiably mythical status. It is simply not known how the ghostly image of a serene, bearded man was made.”

Ball, who understood the chemistry of the shroud’s images, rejected a notion popularized by many news accounts that Leonardo da Vinci created the image using primitive photography. He called the idea flaky. He also debunked the sometimes reported speculation that the image was “burned into the cloth by some kind of release of nuclear energy” from Jesus’ body. This he said was wild.

Almost all serious shroud researchers agree with Ball on these points. When flaky and wild ideas appear in newspaper articles or on television, as they often do, scientists cringe. Rogers referred to those who held such views as being part of the “lunatic fringe” of shroud research. But Rogers was just as critical of those who, without the benefit of solid science, declared the shroud a fake. They, too, were part of the lunatic fringe.

The idea that the shroud had been mended in the area from which the carbon 14 samples had been taken had been floating around for some time. But no one paid much attention. In 1998, Turin’s scientific adviser, Piero Savarino, suggested, “extraneous substances found on the samples and the presence of extraneous thread (left over from ‘invisible mending’ routinely carried on in the past on parts of the cloth in poor repair)” might have accounted for an error in the carbon 14 dating. Longtime shroud researchers Sue Benford and Joe Marino independently developed the same idea and explored it with several textile experts and Ronald Hatfield of the radiocarbon dating firm Beta Analytic. The art of invisible reweaving, Benford and Marino discovered, was commonly used in the Middle Ages to repair tapestries. Why not the shroud, they thought? The believed they saw evidence of it.

But the skeptically minded Rogers did not agree. He had already debunked every other argument so far offered to explain why the carbon 14 dating might be wrong. According to Ball, “Rogers thought that he would be able to ‘disprove [the] theory in five minutes’.” Instead he found clear evidence of discreet mending. He also showed, with chemistry, that the shroud was at least thirteen hundred years old. And he proved, beyond any doubt, that the sample used in 1988 was chemically unlike the rest of the shroud. The samples were invalid. The 1988 tests were thus meaningless.

In words that seem strange in a scientific journal that once had bragging rights to claim that the shroud was not authentic, Ball wrote: “And of course 'authenticity' is not really a scientific issue at all here: even if there were compelling evidence that the shroud was made in first-century Palestine, that would not even come close to establishing that the cloth bears the imprint of Christ.”

One might think the Papal custodians of the Shroud of Turin would be pleased. The head of the skeptical argument, the carbon 14 dating, had been severed. The shroud might be 2000 years old, after all. But like Hydra, the Greek mythological beast, controversy grew a weird new head. The 1988 carbon 14 dating was off the table. And Ball, who was familiar with the evidence, had confirmed what all shroud researchers had been saying for years: the images were not painted. Moreover, a 2003 article in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Melanoidins by Rogers and Anna Arnoldi, a chemistry professor at the University of Milan, demonstrated that the images were in fact a chemical caramel-like darkening of an otherwise clear starch and polysaccharide coating on some of the shroud’s fibers. They suggested a natural phenomenon might be the cause. If this could be proven, the images could be explained in non-miraculous, scientific terms.

The Papal Custodians of the Shroud in Turin were not pleased. They had been responsible for selecting the sample from a corner of the cloth. They had ignored scientific protocols to which they had previously agreed. These protocols called for multiple samples from multiple locations. And in 2002, during a restoration of the shroud, they had examined the area from which the samples were cut and had not found any visual evidence of mending.

But then no one else had noticed it, either. It took microscopy to see spliced threads where newer fibers were dyed to match age-yellowed fibers. It took microchemical analysis to find alizarin dye from madder root, alum and plant gum. This was the dyestuff used in medieval times.

Researchers and thousands of people who follow shroud research were dismayed when, within days of Rogers’ paper, Turin’s Monsignor Giuseppe Ghiberti told an Italian newspaper, “I am astonished that an expert like Rogers could fall into so many inaccuracies in his article. I can only hope, indeed, also think that the C14 dating is rectifiable (the method, in fact, has its own uncertainties), but not on the basis of the 'darn' theory.”

The restoration, itself, was very controversial. Turin officials had done the work in secret. They had scraped the shroud, vacuumed it, wet it with fine mist, and stretched it with weights to remove wrinkles. Forensic material, best studied in situ, such as pollen and dirt, was removed and placed in bottles. Researchers wondered how much blood was scraped away. And they wondered how much the fragile images were damaged or loosened by the stretching and scraping since they are part of a fragile coating that is very thin and easily removed. Many, if not most shroud researchers felt the restoration was scientifically and preservation-wise reckless. The newer evidence in scientific journals was drawing attention to how Turin was caring for the cloth and how they were treating scientific evidence.

This new controversy between researchers and the Papal custodian of the shroud would erupt at a conference in September, 2005.

| IN SUPPORT OF ROGERS’ FINDINGS ON THE CARBON 14 DATING |

|

1) John L. Brown, formerly Principal Research Scientist at the Georgia Tech Research Institute's Energy and Materials Sciences Laboratory at the Georgia Institute of Technology, independently confirmed many of Rogers’ findings.

2) In early 2004, the Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology published an important paper by Lloyd A. Currie. Currie, a highly regarded specialist in the field of carbon 14 dating and an NIST Fellow Emeritus, cited Rogers and Arnoldi (from another paper) and gave their work credence. Currie’s NIST paper also set aside any argument that radiocarbon labs had done anything wrong in dating the Shroud of Turin. It debunked the heat-effect, contamination and bioplastic polymer hypotheses. Significantly, it recognized that discreet mending, soon to be demonstrated by Rogers in his peer-reviewed article, was a viable explanation. And it raised the issue of poor sampling by Turin. According to Currie, the original sampling protocol requiring multiple samples from different locations on the cloth was clearly violated by the Papal Custodians of the Shroud. Had the protocol been followed the discreet mending would have been noticed in 1988.

3) Several textile experts, at the behest of Sue Benford and Joseph Marino, examined documenting photographs of the samples and found visual evidence of reweaving. Based on estimates from these photographs, and an a historically-likely suggested date for reweaving, Ronald Hatfield of the radiocarbon dating firm Beta Analytic estimated that the cloth might be 2000 years old.

4) In 1997, Remi Van Haelst, a Belgium chemist, conducted a series of statistical analyses that strongly challenged the veracity of the conclusions of the C14 dating. Significantly, he found serious disparities in measurements between the three laboratories and between the sub-samples (various tests and observations performed by the labs). Bryan Walsh, a statistician, examined Van Haelst’s work and further studied the measurements. The essential conclusions were that the samples, and indeed the divided samples used in multiple tests, contained different levels of the C14 isotope. The differences were sufficient to conclude that the sample were non-homogeneous and thus of questionable validity. Walsh found a significant relationship between various sub-samples and their distance from the edge of the cloth.

5) Ultraviolet and x-ray photographs, taken in 1978 before the carbon 14 dating samples were taken, show that there are chemical differences between the sample area and surrounding areas of the cloth.

6) In 1988, Edward Hall, then the director of Oxford University's Radiocarbon Laboratory, had seen cotton fibers that might be from mending. That same year, in Textile Horizons in an article entitled "Rogue Fibers Found in Shroud," P. H. Smith suggested that those cotton fibers were suspicious and might have been part of repairs.

Moreover, Rogers found: When the linen wrapping from the Dead Sea Scroll were tested for vanillin, none was found. Vanillin (vanilla) is produced by the thermal decomposition of lignin, a complex polymer non-carbohydrate constituent of plant material including flax. Found in medieval linen but not in much older material, it diminishes and disappears with time. There is no vanillin in the flax fibers of the shroud except in the corner from which the carbon 14 samples were taken. While this is not an accurate method for determining the age of linen because it depends on the average storage temperature over many centuries, it is useful as a gauge or sniff test for checking carbon 14 dating. Assuming that the shroud has been stored at an average temperature 77° Fahrenheit, which is quite warm given that for at least the last seven hundred years it had been stored in northern European cathedrals, it is at least 1300 years old. It could be older but there is no way to know that. On the other hand, linen manufactured in 1260, the oldest date for the shroud determined by carbon 14 testing, should have retained about 37% of its vanillin. Not only does this verify that the carbon 14 sample is chemically different from the rest of shroud, it proves that the carbon 14 sample contains much newer material. |

Every two or three years shroud researchers from around the world gather to share new information and discuss the many enigmatic questions that surround this artifact. The most recent such gathering took place in the grand ballroom of the elegant Adolphus Hotel in downtown Dallas, Texas in September of 2005. About 100 scientists, archeologists and historians representing a broad spectrum of Catholics, Anglicans (Episcopalians), Protestants, Evangelical Christians and non-Christians attended the conference. Most are academics. Many are retired and have time to devote to many hours to the study of the shroud. Almost all believe at some level that the shroud is genuine, even if they cannot prove it. Many share Ball’s view expressed in Nature that if it could be shown to be first century, it would nonetheless be impossible to prove, at least scientifically, that it was Jesus’ burial shroud.

The 2005 Dallas Conference on the Shroud of Turin was unlike previous conferences. It would redefine controversy about this cloth as not so much between skeptics and believers but between researchers and the Papal Custodians on matters of science and preservation.

The conferees were upbeat. Most, for many years, had believed that the 1988 carbon 14 dating was flawed. But they could only suspect why before Rogers completed his peer-reviewed studies. And there had been other recent exciting developments. In April 2004, the peer-reviewed scientific Journal of Optics, published by the Institute of Physics in London, carried a paper by two scientists, Giulio Fanti and Roberto Maggiolo, from the University of Padua in Italy. Using modern image enhancement techniques, the team had discovered a faint image of a face on the backside of the cloth. The press dubbed it the “second face.” It wasn’t clear what it meant, but it was new information for consideration. And there was new analysis of the burn marks and water stains on the cloth. Some of the stains suggested that the cloth had been folded and stored in a jar similar to jars found at Qumran in which some of the Dead Sea Scrolls were stored.

A key document had been prepared over the course of two years. It was a list of about one hundred and fifty scientific facts and confirmed observation, including very recent findings, compiled from over a hundred scientific papers, many of them published in secular peer-reviewed journals. Twenty-eight researchers were listed as authors. The list was entitled “Evidence for Testing Hypotheses about the Body Image Formation of the Turin Shroud.” But most researchers simply called it “The List.” It was to be presented at the conference.

The better understanding of image chemistry was leading to new ideas on how the images formed on the cloth. One hypothesis, getting serious consideration, is a Maillard reaction. Rogers and Arnoldi had proposed it in their paper published in Melanoidins. The hypothesis suggests that volatile body vapors, such as cadaverine and putrescine, reacted with the starch and saccharides film that coats the outermost fibers of the cloth. The images are chemically consistent with this type of reaction. And it is well understood that such vapors from a corpse, given the right conditions, will cause browning on a cloth that has the right sort of residues on its fibers. But if this is how the images formed, it is only hypothetical. There are unresolved problems. And there are possibly other ways to create this caramel-like condition. “Hypothesis,” researchers say, is the right word to use, for no proposal yet meets the scientific criteria needed to be called a theory.

But despite the positive feelings about progress, most attendees were frustrated and angry with the Papal Custodians of the Shroud of Turin. They were angry about the restoration. They were dismayed that Turin officials were ignoring scientific evidence. Many felt that the shroud’s custodians were ignoring advice by the late Pope John Paul II when in 1998 he said, “the Church does not have specific competence to pronounce on these questions. It entrusts to scientists the task of continuing to investigate to find suitable answers to questions regarding the Shroud.”

Ghiberti and textile conservator Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, who had managed the restoration work, were in Dallas to defend the restoration and to reiterate their claim that they had not seen evidence of discreet mending. Scientists and archeologists wanted to ask them questions and express their own views. But conference organizers decided to prohibit questions and comments from the floor. And at the last minute they cancelled a PowerPoint presentation of “The List” which did contain scientific facts that disagreed what Turin officials were saying. When Fanti, who had served as the primary editor of the document, asked why, he was told that the document was “too political.”

Cardinal Angelo Sodano, the Vatican Secretary of State, perhaps having sensed what was to happen in Dallas, had written a letter to the conferees saying, “His Holiness [Pope Benedict XVI] trusts that the Dallas Conference will advance cooperation and dialogue among various groups engaged in scientific research on the Shroud . . .”

But cooperation did not happen. The conferees were undaunted. In a presentation that had been billed as a tribute to the late Raymond Rogers, researcher Barrie Schwortz instead showed an interview with Rogers videotaped shortly before his death on March 8, 2005. In the interview, Rogers explained the discreet mending and why that invalidated the 1988 carbon 14 dating. And he offered a blistering criticism of the secretive restoration. He explained why the cloth and the still-unexplained images of a crucified man may have been damaged during the restoration.

While the conferees applauded the interview Ghiberti walked out of the room, a gesture that perhaps signaled future non-cooperation. It was peculiar because it would be fair to say that probably every researcher in the grand ballroom of the hotel thought the shroud might be the real thing even if they could not prove it.

Controversy between skeptics and believers seemed to be a thing of the past. While skepticism is valid and indeed welcomed, the reasons propounded in the past now seemed moot to the conferees. The argument that the shroud’s images were painted, advanced by microscopist Walter McCrone in 1989, had been refuted. There is no paint. And the medieval carbon 14 dating was now well understood to be meaningless.

Controversy was now between the scientists and the Papal Custodians. The conferees do not want it and they offered suggestions. Why not, for instance, test carbonized fabric dust scraped from the shroud during the restoration, as Rogers proposed in his Thermochimica Acta article? Why not allow high resolution, spectrally sensitive scans of both the front and the backside?

Kim Dreisbach, an Episcopal priest who presented a paper at the conference, had an interesting suggestion: get advice and oversight from the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Involved, as they are, in world health, global warning and cosmology studies, they have access to some of the best scientific minds who could provide advice to Turin on future studies and preservation of the shroud.

| THE OLD “IT WAS PAINTED” CONTROVERSY |

|

It is often reported that microscopist Walter McCrone proved that the images were painted. This is incorrect. McCrone, who examined 32 slides containing fibers from the cloth, found traces of iron oxide which he determined was “jewelers rouge.” He concluded that the images were painted with this. McCrone also claimed to have found a concentration of mercury that he says was used to make vermilion paint used to paint the bloodstains. But chemical investigation shows that small quantities of iron oxide particles are evenly distributed in both image and non-image areas and that the quantities are too small to form a visible image. The bloodstains are from real blood. Different scientists, working independently, conducted immunological, fluorescence and spectrographic tests, as well as Rh and ABO typing of blood antigens that clearly show this. And several experts in forensic medicine and blood chemistry conclude that the stains were formed by real human bleeding from real wounds to a real human body that came into direct contact with the cloth. See the peer reviewed Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, Volume 14 (1981), pp.81-103.

In 1389, Pierre d’Arcis, the Bishop of Troyes, France, drafted a memorandum to Pope Clement VII of Avignon stating that the shroud was a painted forgery. However, there is no historical evidence that draft memorandum was ever finalized or sent. The account of a confession by a painter is second hand. Pierre claimed that his predecessor, Bishop Henri de Poitiers, conducted an inquest in which a painter had confessed to painting the shroud. The inquest is not in the historical records. The painter is not identified. Several other documents of the period challenge the veracity of the d'Arcis Memorandum. The historical conspectus suggests that the memorandum was part of a squabble about revenues from pilgrims visiting the nearby town of Lirey, where the shroud was kept, rather than Troyes.

It is all moot. Visible and ultraviolet spectrometry, infrared spectrometry, x-ray fluorescence spectrometry, pyrolysis-mass-spectrometry, laser-microprobe Raman analyses, and microchemical testing show no evidence of such material in sufficient quantity to form any visible image. Moreover, it is well understood now, that the images are formed by a caramel-like substance within the otherwise clear coating of starch and polysaccharides on outer fibers. McCrone continued to defend his position that the shroud was painted until his death in 2002. The McCrone Institute continues to carry material written by him on the organization’s website, but it (is) out of date. The McCrone Institute in Chicago can be contacted at 312-842-7100 |

The problem of the shroud’s authenticity is usually thought of in scientific terms. And indeed that is where much of the research is focused. But there is much, as well, that can be learned from history. Historians and biblical scholars are constantly probing for new material. Even, today, libraries of ancient documents are being translated that shed new light on the possible provenance of the cloth.

It is often reported that there is no historical record of the shroud before 1356 CE. That is incorrect. However, it is correct to say that there are no known records about the shroud in western medieval Europe before that time.

Several historians believe that the shroud was taken by French knights of the Fourth Crusade during the sacking of Constantinople in 1204. In 1205, Theodore Ducas Anglelos, writing about the looted treasures in a letter to Pope Innocent III wrote, “The Venetians partitioned the treasure of gold, silver and ivory, while the French did the same with the relics of saints and the most sacred of all, the linen in which our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after His death and before the resurrection.”

Moreover, there is certain knowledge that on August 15, 944 CE, an image bearing cloth known as the Cloth of Edessa, was forcibly transferred from Edessa to Constantinople. It had been in Edessa since at least the middle of the 6th century when it was found concealed behind some stones above one of the city gates. It was, when found, to the people of Edessa, the lost cloth of a great legend. According to legend the cloth, with a miraculous picture of Jesus, was brought to Abgar V Ouchama, the King of Edessa from 13 –50 CE, by a disciples known as Thaddeus Jude. According to the legend he was sent by the apostle Thomas.

Whether or not the legend is true is immaterial. In the late 6th century, Evagrius Scholasticus’ Ecclesiastical History mentions that Edessa was protected by a “divinely wrought portrait,” an acheiropoietos sent by Jesus to Abgar. In 730 CE, St. John Damascene describes the cloth as a himation, which is translated as an oblong cloth or grave cloth. Thus, if the Edessa Cloth is the Shroud of Turin, the written record goes back to the sixth century.

By the sixth century, a traditional understanding that Jesus’ image was left on his burial shroud had developed. In Visigothic Spain, there was a formula for worship known as the Mozarabic Rite. One element of the rite was the illatio (Præfatio). There were numerous illationes (proper prefaces) for special days. One used at Eastertide read, “Peter ran with John to the tomb and saw the recent imprints of the dead and risen man on the linens.” The word imprints is a translation of vestigia which can also mean traces or marks. It can also mean footsteps or footprints, but these do not make contextual sense.

In the eighth century Pope Stephen III (reigned 752 to 757 CE) stated that Christ had “spread out his entire body on a linen cloth that was white as snow. On this cloth, marvelous as it is to see . . . the glorious image of the Lord's face, and the length of his entire and most noble body, has been divinely transferred.”

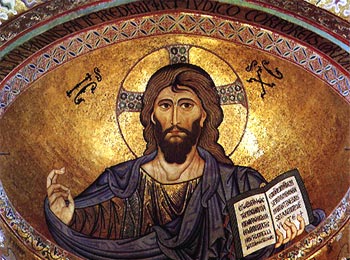

In the sixth century a new common appearance for Jesus emerged in icons, paintings, mosaics and Byzantine coins. And they had an uncanny resemblance to the face of the man of the shroud. Indeed, some scholars think that the shroud was the source for new ideas of what Jesus looked like.

Prior to this time, pictures of Jesus were mostly of a young, beardless man, often with short hair, and often in story-like settings in which he was depicted as a shepherd. Suddenly, Jesus had a forked beard. He looked out at us, in full frontal images, from large owlish eyes. His face was gaunt and his nose was long and thin. Numerous other characteristics appeared in these pictures, and some of them were seemingly strange and of no particular artistic merit.

Many portraits had two wisps of hair that dropped at an angle from a central parting of the hair. Paul Vignon, a French scholar who first categorized these facial attributes in 1930, also described a square cornered U shape between the eyebrows, a downward pointing triangle on the bridge of the nose, a raised right eyebrow, accents on both cheeks with the accent on the right cheek being somewhat lower, an enlarged left nostril, an accent line below the nose, a gap in the beard below the lower lip, and hair on one side of the head that was shorter than on the other side.

The most famous and the earliest of these full frontal pictures of Jesus is Christ Pantocrator, an icon at St. Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai. This icon has been reliably dated to the middle of the sixth century, at just about the time that the Edessa Cloth was found behinds stones above the city’s gate. When one image is overlaid on the other, facial feature locations and shapes are almost perfectly aligned.Hungarian Pray Codex

In the Budapest National Library there is an ancient codex, known commonly as the Hungarian Pray Manuscript or Pray Codex, named for György Pray (1723-1801), a Jesuit scholar who made the first detailed study of it. Written between 1192 and 1195, the codex contains an illustration, one of five in the manuscript, showing Jesus being placed on his burial shroud. The shroud is drawn with the same herringbone weave and identical patterns of small burn holes found on the shroud. (These are not the large burns caused by the fire of 1532. The artist included a number of other graphic characteristics consistent with the shroud. Jesus is shown naked with his arms modestly folded at the wrists. The fingers are unusually long in appearance as they are on the shroud. There are no visible thumbs just as there are no thumbs visible in the images of the man of the shroud. In the drawing, there is also a clear mark on Jesus' forehead where a prominent 3-shaped bloodstain is found on the forehead of the man of the shroud.

| THE STRANGE SHADOW SHROUD IN THE NEWS |

|

Researchers cringed when the late Peter Jennings, on ABC World News Tonight (Mar 22, 2005), in a segment entitled, “Shrouded in Mystery No More,” stated: “The Shroud of Turin has mystified scientists for years. Now a literature professor from Idaho says he can prove it's a fake.” Nathan Wilson, who teaches literature at New St. Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho, ingeniously created an image that to the untrained eye looked something like the shroud. He wrote an article for Christianity Today. Wilson did not claim that he “can prove it's a fake.” What he said, as reported by the Discovery Channel, which also carried the story, was that it “could have been easily forged by painting an image on glass.” The glass was then used as a negative to selectively sun bleach a piece of unbleached linen, creating an image by making some areas lighter rather than darkening other areas. The Discovery Channel went on to report: “Venerated by many Catholics as the proof that Christ was resurrected from the grave and dismissed by some scientists as a brilliant medieval fake, the shroud features the image of a man that is both three-dimensional and a photonegative.” This gives a completely false picture of the controversy as being between Catholics and scientists. Who are these scientists? What about the scientists who think it might genuine? What about the Anglicans, the Protestants and the Evangelical Christians? The Discovery Channel did report on the Thermochimica Acta article by Rogers that “argued that the 1988 carbon-14 dating actually used a sample cut from a rewoven portion of the shroud and not the original.” This prompted an interesting conspiracy theory by Wilson that the new dating did not rule out his hypothesis of a forgery. According to Wilson. “It is extraordinarily unlikely that a forger would use a cloth fresh off the loom. If I was some villainous Crusader, hoping to fake the burial shroud of Christ, the first thing I would do is obtain a burial cloth. And the best place to get one, as well as the cheapest, is from a tomb.” Wilson never mentions how it might be that a shroud would not have decomposed in a tomb after several centuries. Nor did Wilson explain where a medieval forger would have obtained the 7 foot long panes of glass his forger needed. Such pieces of glass did not exist before the nineteenth century. The Discovery Channel also reported that, “Wilson's experiment is also consistent with a 1970s analysis by the late Walter McCrone, a Chicago chemical microscopist, who maintained he had identified the pigment red ochre, and tempera, as the shroud's paint medium, placing it as a medieval painting created around 1355.” But it is not consistent. McCrone argued that the images were painted. Wilson argued that they were not. It is moot. The chemistry of the shroud images is well understood. The image on the shroud, while it can be cleared with a reducing agent, it resists bleaching. By definition, Wilson’s images could be bleached away. What Wilson created was chemically unlike the images on the shroud. Frank Chin, a chemistry professor at the University of Idaho, said of Wilson’s so-called Shadow Shroud, “You can make a glass of nerve toxin look like lemonade. That doesn't make it lemonade.” |

The Shroud of Turin is a single piece of linen, about 14½ feet long by 3½ feet wide (4.4 x 1.1 meters). The weave is very fine 3-over 1-herringbone twill, approximately 350 micrometers thick, about half the thickness of common newsprint paper.

Faint, brownish, full-length frontal and backside images of a man are visible on the cloth’s surface. Discernable wounds within the images suggest that the man was scourged and crucified with spikes driven through his wrists and feet. What appear to be red bloodstains conform to the locations of visible wounds. The fact that the bloodstains appear red has prompted much debate in past years because blood normally turns black with age. But chemical analysis shows that the stains are from human blood. And chemistry also explains why the blood color remains red.

The cloth is severely burn damaged. There are several small burn holes of unknown origin as well as large charred areas and holes from a damaging fire in 1532. Close examination also reveals numerous water stains, some clearly the result of dousing the fire in 1532. Other water stains suggest that the cloth was folded and stored in an earthen jar similar to the urns that held the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The yarn (thread) consists of approximately 70 to 120 flax fibers hand spun together in a Z-twist (clockwise). The numerous lengths (hanks) of yarn used in weaving are not spliced together on the loom but overlapped side-by-side during the weaving. Variegated patterns of whiteness in both the warp and weft yarn indicate that the yarn was bleached before weaving rather than after the cloth was taken from the loom.

The thickness of the flax fibers varies significantly but the average is about 13 micrometers or roughly one-eighth the thickness of typical human hair.

The residue coating of starch fractions and saccharides on the outermost fibers is consistent with an evaporation concentration. This is the sort of residue that forms when trace amounts of these substances in rinse water are moved to the surface as water wicks to the outside of a cloth as it dries. The saccharides in the coating are like those found in Soapwort (saponaria officinalis). These include glucose, fucose, galactose, arabinose, xylose, rhamnose, and glucuronic acid). This coating is about 1 percent to 4 percent of the thickness of the fibers. Where there is image color, the color is completely within, and the result of a caramel-like chemical change to, the otherwise clear evaporation concentration layer.

The residue coating is expected from first century methods of linen manufacturing described by the historian Pliny the Elder. The warp threads on the loom were coated with starch as a lubricant. The cloth was then rinsed with soapwort to remove the starch and laid out to dry. The bleaching of hanks of yarn before weaving is also consistent with first century methods but not consistent with medieval European field bleaching of finished cloth.

Today, the shroud is stored flat in a sealed, fireproof, rare-atmosphere container with bullet proof glass in St. John the Baptist Cathedral (Duomo di San Giovanni) in Turin, Italy. The container is covered with a cloth so that the shroud may not be viewed except during public exhibitions.

Throughout history, the shroud has been stored rolled up or folded in various reliquaries. And as mentioned earlier, there is evidence that it was once stored in an earthen jar.

The last exhibition was in 2000. At that time, the Papal Custodian, Cardinal Saverino Poletto, announced that the next exhibition would be in 2025.

Much more information at ShroudStory.com, Freeper Shroudie's excellent web site on the Shroud of Turin

Both Shroudie's Web Page and the PDF file of the article have excellent photographs that help explain the scientific evidence. Also included are links to sources, scientific articles, and other scholarship on the Shroud.

PING!

|

| Decoding The Past Unraveling the Shroud. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

ping

"He has no stately form or majesty that we should look upon Him, nor appearance that we should be attracted to Him." (Isaiah 53:2)

He sure is beautiful to me. He is my hero.

"Why were you searching for me?" he asked. "Didn't you know I had to be in my Father's house?" (Luke 2:49)

Is this on the Discovery channel?

Thanks for an early Christmas present 8-)

Sounds like more da Vinci crap. I hope not.

Catholic Ping

Please freepmail me if you want on/off this list

MERRY CHRISTMAS EVERYONE !!!!!!

Those are great!

How is the second one done? Is it a negative of the Shroud?

Yes--it is a computer image built using the shroud image as a template and the image is built with eyes to show how He might have looked.

Sorry this is a bit late... no, it was on the History Channel. Swordmaker

The Shroud was first displayed in Lirey, France, about 100 years before Da Vinci was born in 1452. In addition, the Pray Codex displays a drawing of the Shroud that is reliably dated to the 12th Century.

bump for later

So much for da Vinci's "camera" then. Did you see the special? I was out.

Yes. I saw it. I was disappointed.

They spent far too much time on the Da Vinci Camera Obsura canard without pointing out the obvious flaws... no silver shows up on the shroud in sufficient quantities to be visible (there is some silver, but that proably came from the molten silver that burned through the shroud in the fire of 1532), we already KNOW what the image is composed of, and the image does not show LIGHT artifacting... instead it shows contour mapping information, with the darker image areas corresponding to the distance the cloth was from the surface of the body.

No serious scientific researchers give any credance at all to the theory that Da Vinci created the shroud... Da Vinci was born much too late, unless he also invented an undocumented time machine. If he did, he would have had trouble finding a Delorean ;^)>

Very impressive. Thanks, as always.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.