The Mystery of Fascism![]()

by David Ramsay Steele

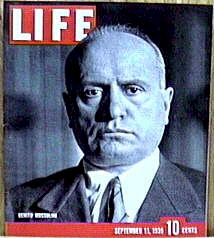

Mussolini - as he would like to have been remembered

You're the top!

You're the Great Houdini!

You're the top!

You are Mussolini! (1)

Soon after he arrived in Switzerland in 1902, 18 years old and looking for work, Benito Mussolini was starving and penniless. All he had in his pockets was a cheap nickel medallion of Karl Marx.

Following a spell of vagrancy, Mussolini found a job as a bricklayer and union organizer in the city of Lausanne. Quickly achieving fame as an agitator among the Italian migratory laborers, he was referred to by a local Italian-language newspaper as "the great duce [leader] of the Italian socialists." He read voraciously, learned several foreign languages, (2) and sat in on Pareto's lectures at the university.

The great duce's fame was so far purely parochial. Upon his return to Italy, young Benito was an undistinguished member of the Socialist Party. He began to edit his own little paper, La Lotta di Classe (The Class Struggle), ferociously anti-capitalist, anti-militarist, and anti-Catholic. He took seriously Marx's dictum that the working class has no country, and vigorously opposed the Italian military intervention in Libya. Jailed several times for involvement in strikes and anti-war protests, he became something of a leftist hero. Before turning 30, Mussolini was elected to the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party, and made editor of its daily paper, Avanti! The paper's circulation and Mussolini's personal popularity grew by leaps and bounds.

Mussolini's election to the Executive was part of the capture of control of the Socialist Party by the hard-line Marxist left, with the expulsion from the Party of those deputies (members of parliament) considered too conciliatory to the bourgeoisie. The shift in Socialist Party control was greeted with delight by Lenin and other revolutionaries throughout the world.

From 1912 to 1914, Mussolini was the Che Guevara of his day, a living saint of leftism. Handsome, courageous, charismatic, an erudite Marxist, a riveting speaker and writer, a dedicated class warrior to the core, he was the peerless duce of the Italian Left. He looked like the head of any future Italian socialist government, elected or revolutionary.

In 1913, while still editor of Avanti!, he began to publish and edit his own journal, Utopia, a forum for controversial discussion among leftwing socialists. Like many such socialist journals founded in hope, it aimed to create a highly-educated cadre of revolutionaries, purged of dogmatic illusions, ready to seize the moment. Two of those who collaborated with Mussolini on Utopia would go on to help found the Italian Communist Party and one to help found the German Communist Party. (3) Others, with Mussolini, would found the Fascist movement.

The First World War began in August 1914 without Italian involvement. Should Italy join Britain and France against Germany and Austria, or stay out of the war? (4) All the top leaders and intellectuals of the Socialist Party, Mussolini among them, were opposed to Italian participation.

In October and November 1914, Mussolini switched to a pro-war position. He resigned as editor of Avanti!, joined with pro-war leftists outside the Socialist Party, and launched a new pro-war socialist paper, Il Popolo d'Italia (People of Italy). (5) To the Socialist Party leadership, this was a great betrayal, a sell-out to the whoremasters of the bourgeoisie, and Mussolini was expelled from the Party. It was as scandalous as though, 50 years later, Guevara had announced that he was off to Vietnam, to help defend the South against North Vietnamese aggression.

Italy entered the war in May 1915, and Mussolini enlisted. In 1917 he was seriously wounded and hospitalized, emerging from the war the most popular of the pro-war socialists, a leader without a movement. Post-war Italy was hag-ridden by civil strife and political violence. Sensing a revolutionary situation in the wake of Russia's Bolshevik coup, the left organized strikes, factory occupations, riots, and political killings. Socialists often beat up and sometimes killed soldiers returning home, just because they had fought in the war. Assaulting political opponents and wrecking their property became an everyday occurrence.

Mussolini and a group of adherents launched the Fascist movement (6) in 1919. The initiators were mostly men of the left: revolutionary syndicalists and former Marxists. (7) They took with them some non-socialist nationalists and futurists, and recruited heavily among soldiers returning from the war, so that the bulk of rank-and-file Fascists had no leftwing background. The Fascists adopted the black shirts (8) of the anarchists and Giovinezza (Youth), the song of the front-line soldiers.

Apart from its ardent nationalism and pro-war foreign policy, the Fascist program was a mixture of radical left, moderate left, democratic, and liberal measures, and for more than a year the new movement was not notably more violent than other socialist groupings. (9) However, Fascists came into conflict with Socialist Party members and in 1920 formed a militia, the squadre (squads). Including many patriotic veterans, the squads were more efficient at arson and terror tactics than the violently disposed but bumbling Marxists, and often had the tacit support of the police and army. By 1921 Fascists had the upper hand in physical combat with their rivals of the left.

The democratic and liberal elements in Fascist preaching rapidly diminished and in 1922 Mussolini declared that "The world is turning to the right." The Socialists, who controlled the unions, called a general strike. Marching into some of the major cities, blackshirt squads quickly and forcibly suppressed the strike, and most Italians heaved a sigh of relief. This gave the blackshirts the idea of marching on Rome to seize power. As they publicly gathered for the great march, the government decided to avert possible civil war by bringing Mussolini into office; the King "begged" Mussolini to become Prime Minister, with emergency powers. Instead of a desperate uprising, the March on Rome was the triumphant celebration of a legal transfer of authority.

The youngest prime minister in Italian history, Mussolini was an adroit and indefatigable fixer, a formidable wheeler and dealer in a constitutional monarchy which did not become an outright and permanent dictatorship until December 1925, and even then retained elements of unstable pluralism requiring fancy footwork. He became world-renowned as a political miracle worker. Mussolini made the trains run on time, closed down the Mafia, drained the Pontine marshes, and solved the tricky Roman Question, finally settling the political status of the Pope.

Cole Porter -- sang Mussolini's praises

Mussolini was showered with accolades from sundry quarters. Winston Churchill called him "the greatest living legislator." Cole Porter gave him a terrific plug in a hit song. Sigmund Freud sent him an autographed copy of one of his books, inscribed to "the Hero of Culture." (10) The more taciturn Stalin supplied Mussolini with the plans of the May Day parades in Red Square, to help him polish up his Fascist pageants.

The rest of il Duce's career is now more familiar. He conquered Ethiopia, made a Pact of Steel with Germany, introduced anti-Jewish measures in 1938, (11) came into the war as Hitler's very junior partner, tried to strike out on his own by invading the Balkans, had to be bailed out by Hitler, was driven back by the Allies, and then deposed by the Fascist Great Council, rescued from imprisonment by SS troops in one of the most brilliant commando operations of the war, installed as head of a new "Italian Social Republic," and killed by Communist partisans in April 1945.

Given what most people today think they know about Fascism, this bare recital of facts (12) is a mystery story. How can a movement which epitomizes the extreme right be so strongly rooted in the extreme left? What was going on in the minds of dedicated socialist militants to turn them into equally dedicated Fascist militants?

What They Told Us about Fascism

In the 1930s, the perception of "fascism" (13) in the English-speaking world morphed from an exotic, even chic, Italian novelty (14) into an all-purpose symbol of evil. Under the influence of leftist writers, a view of fascism was disseminated which has remained dominant among intellectuals until today. It goes as follows:

Fascism is capitalism with the mask off. It's a tool of Big Business, which rules through democracy until it feels mortally threatened, then unleashes fascism. Mussolini and Hitler were put into power by Big Business, because Big Business was challenged by the revolutionary working class. (15) We naturally have to explain, then, how fascism can be a mass movement, and one that is neither led nor organized by Big Business. The explanation is that Fascism does it by fiendishly clever use of ritual and symbol. Fascism as an intellectual doctrine is empty of serious content, or alternatively, its content is an incoherent hodge-podge. Fascism's appeal is a matter of emotions rather than ideas. It relies on hymn-singing, flag-waving, and other mummery, which are nothing more than irrational devices employed by the Fascist leaders who have been paid by Big Business to manipulate the masses.

As Marxists used to say, fascism "appeals to the basest instincts," implying that leftists were at a disadvantage because they could appeal only to noble instincts like envy of the rich. Since it is irrational, fascism is sadistic, nationalist, and racist by nature. Leftist regimes are also invariably sadistic, nationalist, and racist, but that's because of regrettable mistakes or pressure of difficult circumstances. Leftists want what's best but keep meeting unexpected setbacks, whereas fascists have chosen to commit evil.

More broadly, fascism may be defined as any totalitarian regime which does not aim at the nationalization of industry but preserves at least nominal private property. The term can even be extended to any dictatorship that has become unfashionable among intellectuals. (16) When the Soviet Union and People's China had a falling out in the 1960s, they each promptly discovered that the other fraternal socialist country was not merely capitalist but "fascist." At the most vulgar level, "fascist" is a handy swear-word for such hated figures as Rush Limbaugh or John Ashcroft who, whatever their faults, are as remote from historical Fascism as anyone in public life today.

The consequence of 70 years of indoctrination with a particular leftist view of fascism is that Fascism is now a puzzle. We know how leftists in the 1920s and 1930s thought because we knew people in college whose thinking was almost identical, and because we have read such writers as Sartre, Hemingway, and Orwell.

But what were Fascists thinking?

Some Who Became Fascists

Robert Michels was a German Marxist disillusioned with the Social Democrats. He became a revolutionary syndicalist. In 1911 he wrote Political Parties, a brilliant analytic work, (17) demonstrating the impossibility of "participatory democracy"--a phrase that was not to be coined for half a century, but which accurately captures the early Marxist vision of socialist administration. (18) Later he became an Italian (changing "Robert" to "Roberto") and one of the leading Fascist theoreticians.

Hendrik de Man was the leading Belgian socialist of his day and recognized as one of the two or three most outstanding socialist intellects in Europe--many in the 1930s believed him to be the most important socialist theoretician since Marx. He is the most prominent of the numerous Western European Marxists who wrestled their way from Marxism to Fascism or National Socialism in the interwar years. In more than a dozen thoughtful books from The Remaking of a Mind (1919), via The Socialist Idea (1933), to Après Coup (1941) de Man left a detailed account of the theoretical odyssey which led him, by 1940, to acclaim the Nazi subjugation of Europe as "a deliverance." His journey began, as such journeys so often did, with the conviction that Marxism needed to be revised along "idealist" and psychological lines. (19)

Two avant-garde artistic movements which contributed to the Fascist worldview were Futurism and Vorticism. Futurism was the brainchild of Filippo Marinetti, who eventually lost his life in the service of Mussolini's regime. You can get some idea of the Futurist pictorial style from the credits for the Poirot TV series. Its style of poetry was a defining influence on Mayakovsky. Futurist arts activities were permitted for some years in the Soviet Union. Futurism held that modern machines were more beautiful than classical sculptures. It lauded the esthetic value of speed, intensity, modern machinery, and modern war.

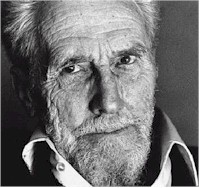

Pound, found to be mentally ill because he supported fascism"

Vorticism was a somewhat milder variant of Futurism, associated with Ezra Pound and the painter and novelist Wyndham Lewis, an American and a Canadian who transplanted to London. Pound became a Fascist, moved to Italy, and was later found mentally ill and incarcerated by the occupying Americans. The symptoms of his illness were his Fascist beliefs. He was later released, and chose to move back to Italy in 1958, an unreprentant Fascist.

In 1939 the avowed fascist Wyndham Lewis retracted his earlier praise for Hitler, but never renounced his basically fascist political worldview. Lewis was, like George Bernard Shaw, one of those intellectuals of the 1930s who admired Fascism and Communism about equally, praising them both while insisting on their similarity.

Fascism must have been a set of ideas which inspired educated individuals who thought of themselves as extremely up-to-date. But what were those ideas?

Five Facts about Fascism

Over the last 30 years, scholarship has gradually begun to bring us a more accurate appreciation of what Fascism was. (20) The picture that emerges from ongoing research into the origins of Fascism is not yet entirely clear, but it's clear enough to show that the truth cannot be reconciled with the conventional view. We can highlight some of the unsettling conclusions in five facts:

Fascism was a doctrine well elaborated years before it was named. The core of the Fascist movement launched officially in the Piazza San Sepolcro on 23rd March 1919 was an intellectual and organizational tradition called "national syndicalism."

As an intellectual edifice, Fascism was mostly in place by about 1910. Historically, the taproot of Fascism lies in the 1890s--in the "Crisis of Marxism" and in the interaction of nineteenth-century revolutionary socialism with fin de siècle anti-rationalism and anti-liberalism.

Fascism changed dramatically between 1919 and 1922, and again changed dramatically after 1922. This is what we expect of any ideological movement which comes close to power and then attains it. Bolshevism (renamed Communism in 1920) also changed dramatically, several times over.

Many of the older treatments of Fascism are misleading because they cobble together Fascist pronouncements, almost entirely from after 1922, reflecting the pressures on a broad and flexible political movement solidifying its rule by compromises, and suppose that by this method they can isolate the character and motivation of Fascist ideology. It is as if we were to reconstruct the ideas of Bolshevism by collecting the pronouncements of the Soviet government in 1943, which would lead us to conclude that Marxism owed a lot to Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great.

Fascism was a movement with its roots primarily in the left. Its leaders and initiators were secular-minded, highly progressive intellectuals, hard-headed haters of existing society and especially of its most bourgeois aspects.

There were also non-leftist currents which fed into Fascism; the most prominent was the nationalism of Enrico Corradini. This anti-liberal, anti-democratic movement was preoccupied with building Italy's strength by accelerated industrialization. Though it was considered rightwing at the time, Corradini called himself a socialist, and similar movements in the Third World would later be warmly supported by the left.

Fascism was intellectually sophisticated. Fascist theory was more subtle and more carefully thought out than Communist doctrine. As with Communism, there was a distinction between the theory itself and the "line" designed for a broad public. Fascists drew upon such thinkers as Henri Bergson, William James, Gabriel Tarde, Ludwig Gumplowicz, Vilfredo Pareto, Gustave Le Bon, Georges Sorel, Robert Michels, Gaetano Mosca, Giuseppe Prezzolini, Filippo Marinetti, A.O. Olivetti, Sergio Panunzio, and Giovanni Gentile.

Here we should note a difference between Marxism and Fascism. The leader of a Marxist political movement is always considered by his followers to be a master of theory and a theoretical innovator on the scale of Copernicus. Fascists were less prone to any such delusion. Mussolini was more widely-read than Lenin and a better writer, but Fascist intellectuals did not consider him a major contributor to the body of Fascist theory, more a leader of genius who could distil theory into action.

Fascists were radical modernizers. By temperament they were neither conservative nor reactionary. Fascists despised the status quo and were not attracted by a return to bygone conditions. Even in power, despite all its adaptations to the requirements of the immediate situation, and despite its incorporation of more conservative social elements, Fascism remained a conscious force for modernization. (21)

Two Revisions of Marxism

Fascism began as a revision of Marxism by Marxists, a revision which developed in successive stages, so that these Marxists gradually stopped thinking of themselves as Marxists, and eventually stopped thinking of themselves as socialists. They never stopped thinking of themselves as anti-liberal revolutionaries.

The Crisis of Marxism occurred in the 1890s. Marxist intellectuals could claim to speak for mass socialist movements across continental Europe, yet it became clear in those years that Marxism had survived into a world which Marx had believed could not possibly exist. The workers were becoming richer, the working class was fragmented into sections with different interests, technological advance was accelerating rather than meeting a roadblock, the "rate of profit" was not falling, the number of wealthy investors ("magnates of capital") was not falling but increasing, industrial concentration was not increasing, (22) and in all countries the workers were putting their country above their class.

In high theory, too, the hollowness of Marxism was being exposed. The long-awaited publication of Volume III of Marx's Capital in 1894 revealed that Marx simply had no serious solution to the "great contradiction" between Volumes I-II and the real behavior of prices. Böhm-Bawerk's devastating critiques of Marxian economics (1884 and 1896) were widely read and discussed.

Eduard Bernstein -- a Marxist revisionist

The Crisis of Marxism gave birth to the Revisionism of Eduard Bernstein, which concluded, in effect, that the goal of revolution should be given up, in favor of piecemeal reforms within capitalism. (23) This held no allure for men of the hard left who rejected existing society, deeming it too loathsome to be reformed. Revisionists also began to attack the fundamental Marxist doctrine of historical materialism--the theory that a society's organization of production decides the character of all other social phenomena, including ideas.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, leftists who wanted to be as far left as they could possibly be became syndicalists, preaching the general strike as the way to demonstrate the workers' power and overthrow the bourgeois order. Syndicalist activity erupted across the world, even in Britain and the United States. Promotion of the general strike was a way of defying capitalism and at the same time defying those socialists who wanted to use electoral methods to negotiate reforms of the system.

Syndicalists began as uncompromising Marxists, but like Revisionists, they acknowledged that key tenets of Marxism had been refuted by the development of modern society. Most syndicalists came to accept much of Bernstein's argument against traditional Marxism, but remained committed to the total rejection, rather than democratic reform, of existing society. They therefore called themselves "revolutionary revisionists." They favored the "idealist revision of Marx," meaning that they believed in a more independent role for ideas in social evolution that that allowed by Marxist theory.

Practical Anti-Rationalism

In setting out to revise Marxism, syndicalists were most strongly motivated by the desire to be effective revolutionaries, not to tilt at windmills but to achieve a realistic understanding of the way the world works. In criticizing and re-evaluating their own Marxist beliefs, however, they naturally drew upon the intellectual fashions of the day, upon ideas that were in the air during this period known as the fin de siècle. The most important cluster of such ideas is "anti-rationalism."

Many forms of anti-rationalism proliferated throughout the nineteenth century. The kind of anti-rationalism which most influenced pre-fascists was not primarily the view that something other than reason should be employed to decide factual questions (epistemological anti-rationalism). It was rather the view that, as a matter of sober recognition of reality, humans are not solely or even chiefly motivated by rational calculation but more by intuitive "myths" (practical anti-rationalism). Therefore, if you want to understand and influence people's behavior, you had better acknowledge that they are not primarily self-interested, rational calculators; they are gripped and moved by myths. (24)

Paris was the fashion center of the intellectual world, dictating the rise and fall of ideological hemlines. Here, anti-rationalism was associated with the philosophy of Henri Bergson, William James's Pragmatism from across the Atlantic, and the social-psychological arguments of Gustave Le Bon. Such ideas were seen as valuing action more highly than cogitation and as demonstrating that modern society (including the established socialist movement) was too rationalistic and too materialistic. Bergson and James were also read, however, as contending that humans did not work with an objectively existing reality, but created reality by imposing their own will upon the world, a claim that was also gleaned (rightly or wrongly) from Hegel, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. French intellectuals turned against Descartes, the rationalist, and rehabilitated Pascal, the defender of faith. In the same spirit, Italian intellectuals rediscovered Vico.

Practical anti-rationalism entered pre-Fascism through Georges Sorel (25) and his theory of the "myth." This influential socialist writer began as an orthodox Marxist. An extreme leftist, he naturally became a syndicalist, and soon the best-known syndicalist theoretician. Sorel then moved to defending Marx's theory of the class struggle in a new way--no longer as a scientific theory, but instead as a "myth", an understanding of the world and the future which moves men to action. When he began to abandon Marxism, both because of its theoretical failures and because of its excessive "materialism," he looked for an alternative myth. Experience of current and recent events showed that workers had little interest in the class struggle but were prone to patriotic sentiment. By degrees, Sorel shifted his position, until at the end of his life he became nationalistic and anti-semitic. (26) He died in 1922, hopeful about Lenin and more cautiously hopeful about Mussolini.

A general trend throughout revolutionary socialism from 1890 to 1914 was that the most revolutionary elements laid an increasing stress upon leadership, and downplayed the autonomous role of the toiling masses. This elitism was a natural outcome of the revolutionaries' ardent wish to have revolution and the stubborn disinclination of the working class to become revolutionary. (27) Workers were instinctive reformists: they wanted a fair shake within capitalism and nothing more. Since the workers did not look as if they would ever desire a revolution, the small group of conscious revolutionaries would have to play a more decisive role than Marx had imagined. That was the conclusion of Lenin in 1902. (28) It was the conclusion of Sorel. And it was the conclusion of the syndicalist Giuseppe Prezzolini whose works in the century's first decade Mussolini reviewed admiringly. (29)

The leadership theme was reinforced by the theoretical writings of, Mosca, Pareto, and Michels, especially Pareto's theory of the Circulation of Elites. All these arguments emphasized the vital role of active minorities and the futility of expecting that the masses would ever, left to themselves, accomplish anything. Further corroboration came from Le Bon's sensational best-seller of 1895--it would remain perpetually in print in a dozen languages--The Psychology of Crowds, which analyzed the "irrational" behavior of humans in groups and drew attention to the group's proclivity to place itself in the hands of a strong leader, who could control the group as long as he appealed to certain primitive or basic beliefs. (30)

The initiators of Fascism saw anti-rationalism as high-tech. It went with their fast cars and airplanes. Fascist anti-rationalism, like psychoanalysis, conceives of itself as a practical science which can channel elemental human drives in a useful direction.

A Marxist Heresy?

Some people have reacted to Fascism by saying that it's just the same as socialism. In part, this arises from the fact that "fascism" is a word used loosely to denote all the non-Communist dictatorships of the 1920s and 1930s, and by extension to refer to the most powerful and horrible of these governments, that of German National Socialism.

The Nazis never claimed to be Fascists, but they did continually claim to be socialists, whereas Fascism, after 1921, repudiated socialism by name. Although Fascism had some influence on the National Socialist German Workers' Party, other influences were greater, notably Communism and German nationalism.

A. James Gregor has argued that Fascism is a Marxist heresy, (31) a claim that has to be handled with care. Marxism is a doctrine whose main tenets can be listed precisely: class struggle, historical materialism, surplus-value, nationalization of the means of production, and so forth. Nearly all of those tenets were explicitly repudiated by the founders of Fascism, and these repudiations of Marxism largely define Fascism. Yet however paradoxical it may seem, there is a close ideological relationship between Marxism and Fascism. We may compare this with the relationship between, say, Christianity and Unitarianism. Unitarianism repudiates all the distinctive tenets of Christianity, yet is still clearly an offshoot of Christianity, preserving an affinity with its parental stem.

In power, the actual institutions of Fascism and Communism tended to converge. In practice, the Fascist and National Socialist regimes increasingly tended to conform to what Mises calls "the German pattern of Socialism." (32) Intellectually, Fascists differed from Communists in that they had to a large extent thought out what they would do, and they then proceeded to do it, whereas Communists were like hypnotic subjects, doing one thing and rationalizing it in terms of a completely different and altogether impossible thing.

Fascists preached the accelerated development of a backward country. Communists continued to employ the Marxist rhetoric of world socialist revolution in the most advanced countries, but this was all a ritual incantation to consecrate their attempt to accelerate the development of a backward country. Fascists deliberately turned to nationalism as a potent myth. Communists defended Russian nationalism and imperialism while protesting that their sacred motherland was an internationalist workers' state. Fascists proclaimed the end of democracy. Communists abolished democracy and called their dictatorship democracy. Fascists argued that equality was impossible and hierarchy ineluctable. Communists imposed a new hierarchy, shot anyone who advocated actual equality, but never ceased to babble on about the equalitarian future they were "building". Fascists did with their eyes open what Communists did with their eyes shut. This is the truth concealed in the conventional formula that Communists were well-intentioned and Fascists evil-intentioned.

Disappointed Revolutionaries

Though they respected "the irrational" as a reality, the initiators of Fascism were not themselves swayed by wilfully irrational considerations. (33) They were not superstitious. Mussolini in 1929, when he met with Cardinal Gasparri at the Lateran Palace, was no more a believing Catholic than Mussolini the violently anti-Catholic polemicist of the pre-war years, (34) but he had learned that in his chosen career as a radical modernizing politician, it was a waste of time to bang his head against the brick wall of institutionalized faith.

Leftists often imagine that Fascists were afraid of a revolutionary working-class. Nothing could be more comically mistaken. Most of the early Fascist leaders had spent years trying to get the workers to become revolutionary. As late as June 1914, Mussolini took part enthusiastically, at risk of his own life and limb, in the violent and confrontational "red week." The initiators of Fascism were mostly seasoned anti-capitalist militants who had time and again given the working class the benefit of the doubt. The working class, by not becoming revolutionary, had let these revolutionaries down.

Preferred Fascism to Marxism

In the late 1920s, people like Winston Churchill and Ludwig von Mises saw Fascism as a natural and salutory response to Communist violence. (35) They already overlooked the fact that Fascism represented an independent cultural phenomenon which predated the Bolshevik coup. It became widely accepted that the future lay with either Communism or Fascism, and many people chose what they considered the lesser evil. Evelyn Waugh remarked that he would choose Fascism over Marxism if he had to, but he did not think he had to.

It's easy to see that the rise of Communism stimulated the rise of Fascism. But since the existence of the Soviet regime was what chiefly made Communism attractive, and since Fascism was an independent tradition of revolutionary thinking, there would doubtless have been a powerful Fascist movement even in the absence of a Bolshevik regime. At any rate, after 1922, the same kind of influence worked both ways: many people became Communists because they considered that the most effective way to combat the dreaded Fascism. Two rival gangs of murderous politicos, bent on establishing their own unchecked power, each drummed up support by pointing to the horrors that the other gang would unleash. Whatever the shortcomings of any such appeal, the horrors themselves were all too real. (36)

From Liberism to the Corporate State

In Fascism's early days it encompassed an element of what was called "liberism," the view that capitalism and the free market ought to be left intact, that it was sheer folly for the state to involve itself in "production."

Marx had left a strange legacy: the conviction that resolute pursuit of the class struggle would automatically take the working class in the direction of communism. Since practical experience offers no corroboration for this surmise, Marxists have had to choose between pursuing the class struggle (making trouble for capitalism and hoping that something will turn up) and trying to seize power to introduce communism (which patently has nothing to do with strikes for higher wages or with such political reforms as factory safety legislation). As a result, Marxists came to worship "struggle" for its own sake. And since Marxists were frequently embarrassed to talk about problems a communist society might face, dismissing any such discussion as "utopian", it became easy for them to argue that we should focus only on the next step in the struggle, and not be distracted by speculation about the remote future.

Traditional Marxists had believed that much government interference, such as protective tariffs, should be opposed, as it would slow down the development of the productive forces (technology) and thereby delay the revolution. For this reason, a Marxist should favor free trade. (37) Confronted by a growing volume of legislative reforms, some revolutionaries saw these as shrewd concessions by the bourgeoisie to take the edge off class antagonism and thus stabilize their rule. The fact that such legislative measures were supported by democratic socialists, who had been co-opted into the established order, provided an additional motive for revolutionaries to take the other side.

All these influences might persuade a Marxist that capitalism should be left intact for the foreseeable future. In Italy, a further motive was that Marxists expected the revolution to break out in the industrially advanced countries. No Marxist thought that socialism had anything to offer a backward economy like Italy, unless the revolution occurred first in Britain, America, Germany, and France. As the prospect of any such revolution became less credible, the issue of Italian industrial development was all that remained, and that was obviously a task for capitalism.

After 1919, the Fascists developed a theory of the state; until then this was the one element in Fascist political theory which had not been elaborated. Its elaboration, in an extended public debate, gave rise to the "totalitarian" view of the state, (38) notoriously expounded in Mussolini's formula, "Everything in the state, nothing against the state, nothing outside the state." Unlike the later National Socialists of Germany, the Fascists remained averse to outright nationalization of industry. But, after a few years of comparative non-intervention, and some liberalization, the Fascist regime moved towards a highly interventionist policy, and Fascist pronouncements increasingly harped on the "corporate state." All traces of liberism were lost, save only for the insistence that actual nationalization be avoided. Before 1930, Mussolini stated that capitalism had centuries of useful work to do (a formulation that would occur only to a former Marxist); after 1930, because of the world depression, he spoke as if capitalism was finished and the corporate state was to replace it rather than providing its framework.

As the dictatorship matured, Fascist rhetoric increasingly voiced explicit hostility to the individual ego. Fascism had always been strongly communitarian but now this aspect became more conspicuous. Fascist anti-individualism is summed up in the assertion that the death of a human being is like the body's loss of a cell. Among the increasingly histrionic blackshirt meetings from 1920 to 1922 were the funeral services. When the name of a comrade recently killed by the Socialists was called out, the whole crowd would roar: "Presente!"

Man is not an atom, man is essentially social--these woolly clichés were as much Fascist as they were socialist. Anti-individualism was especially prominent in the writings of official philosopher Giovanni Gentile, who gave Fascist social theory its finished form in the final years of the regime. (39)

The Failure of Fascism

Fascist ideology had two goals by which Fascism's performance may reasonably be judged: the creation of a heroically moral human being, in a heroically moral social order, and the accelerated development of industry, especially in backward economies like Italy.

The fascist moral ideal, upheld by writers from Sorel to Gentile, is something like an inversion of the caricature of a Benthamite liberal. The fascist ideal man is not cautious but brave, not calculating but resolute, not sentimental but ruthless, not preoccupied with personal advantage but fighting for ideals, not seeking comfort but experiencing life intensely. The early Fascists did not know how they would install the social order which would create this "new man," but they were convinced that they had to destroy the bourgeois liberal order which had created his opposite.

Even as late as 1922 it was not clear to Fascists that Fascism, the "third way" between liberalism and socialism, would set up a bureaucratic police state, but given the circumstances and fundamental Fascist ideas, nothing else was feasible. Fascism introduced a form of state which was claustrophobic in its oppressiveness. The result was a population of decidedly unheroic mediocrities, sly conformists scared of their own shadows, worlds removed from the kind of dynamic human character the Fascists had hoped would inherit the Earth.

As for Fascism's economic performance, a purely empirical test of results is inconclusive. In its first few years, the Mussolini government's economic measures were probably more liberalizing than restrictive. The subsequent turn to intrusive corporatism was swiftly followed by the world slump and then the war. But we do know from numerous other examples that if it is left to run its course, corporatist interventionism will cripple any economy. (40) Furthermore, economic losses inflicted by the war can be laid at Fascism's door, as Mussolini could easily have kept Italy neutral. Fascism both gave unchecked power to a single individual to commit such a blunder as to take Italy to war in 1940 and made this more likely by extolling the benefits of war.

In the panoramic sweep of history, Fascism, like Communism, like all forms of socialism, and like today's greenism and anti-globalism, is the logical result of specific intellectual errors about human progress. Fascism was an attempt to pluck the material fruits of liberal economics while abolishing liberal culture. (41) The attempt was entirely quixotic: there is no such thing as economic development without free-market capitalism and there is no such thing as free-market capitalism without the recognition of individual rights. The revulsion against liberalism was the outcome of misconceptions, and the futile attempt to supplant liberalism was the application of further misconceptions. By losing the war, Fascism and National Socialism spared themselves the terminal sclerosis which beset Communism.

"The Man Who Is Seeking"

When Mussolini switched from anti-war to pro-war in November 1914, the other Socialist Party leaders immediately claimed that he had been bought off by the bourgeoisie, and this allegation has since been repeated by many leftists. But any notion that Mussolini sold out is more far-fetched than the theory that Lenin seized power because he was paid by the German government to take Russia out of the war. As the paramount figure of the Italian left, Mussolini had it made. He was taking a career gamble at very long odds by provoking his own expulsion from the Socialist Party, in addition to risking his life as a front-line soldier. (42)

Like Lenin, Mussolini was a capable revolutionary who took care of finances. Once he had decided to come out as pro-war, he foresaw that he would lose his income from the Socialist Party. He approached wealthy Italian patriots to get support for Il Popolo d'Italia, but much of the money that came to Mussolini originated covertly from Allied governments who wanted to bring Italy into the war. Similarly, Lenin's Bolsheviks took aid from wealthy backers and from the German government. (43) In both cases, we see a determined group of revolutionaries using their wits to raise money in pursuit of their goals.

Jasper Ridley argues that Mussolini switched because he always "wanted to be on the winning side", and dare not "swim against the tide of public opinion." (44) This explanation is feeble. Mussolini had spent all his life in an antagonistic position to the majority of Italians, and with the founding of a new party in 1919 he would again deliberately set himself at odds with the majority. Since individuals are usually more influenced by the pressure of their "reference group" than by the opinions of the whole population, we might wonder why Mussolini did not swim with the tide of the Socialist Party leadership and the majority of the Party membership, instead of swimming with the tide of those socialists inside and outside the Party who had become pro-war.

Although his personality may have influenced the timing, or even the actual decision, the pressure for Mussolini to change his position came from a long-term evolution in his intellectual convictions. From his earliest years as a Marxist revolutionary, Mussolini had been sympathetic to syndicalism, and then an actual syndicalist. Unlike other syndicalists, he remained in the Socialist Party, and as he rose within it, he continued to keep his ears open to those syndicalists who had left it. On many issues, his thinking followed theirs, more cautiously, and often five or ten years behind them.

From 1902 to 1914, Italian revolutionary syndicalism underwent a rapid evolution. Always opposed to parliamentary democracy, Italian syndicalists, under Sorel's influence, became more committed to extra-constitutional violence and the necessity for the revolutionary vanguard to ignite a conflagration. As early as 1908, Mussolini the syndicalist Marxist had come to agree with these elitist notions and began to employ the term gerarchia (hierarchy), which would remain a favorite word of his into the Fascist period.

Many syndicalists lost faith in the revolutionary potential of the working class. Seeking an alternative revolutionary recipe, the most "advanced" of these syndicalists began to ally themselves with the nationalists and to favor war. Mussolini's early reaction to this trend was the disgust we might expect from any self-respecting leftist. (45) But given their premises, the syndicalists' conclusions were persuasive.

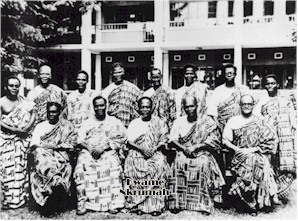

Nkrumah and friends face the camera

The logic underlying their shifting position was that there was unfortunately going to be no working-class revolution, either in the advanced countries, or in less developed countries like Italy. Italy was on its own, and Italy's problem was low industrial output. (46) Italy was an exploited proletarian nation, while the richer countries were bloated bourgeois nations. The nation was the myth which could unite the productive classes behind a drive to expand output. These ideas foreshadowed the Third World propaganda of the 1950s and 1960s, in which aspiring elites in economically backward countries represented their own less than scrupulously humane rule as "progressive" because it would accelerate Third World development. From Nkrumah to Castro, Third World dictators would walk in Mussolini's footsteps. (47) Fascism was a full dress rehearsal for post-war Third Worldism.

Nixon and friend caught by the camera

Many syndicalists also became "productionists," urging that the workers ought not to strike, but to take over the factories and keep them running without the bosses. While productionism as a tactic of industrial action did not lead anywhere, the productionist idea implied that all who helped to expand output, even a productive segment of the bourgeoisie, should be supported rather than opposed.

From about 1912, those who closely observed Mussolini noted changes in his rhetoric. He began to employ the words "people" and "nation" in preference to "proletariat." (Subsequently such patriotic language would become acceptable among Marxists, but then it was still unusual and somewhat suspect.) Mussolini was gradually becoming convinced, a few years later than the most advanced leaders of the extreme left, that Marxist class analysis was useless, that the proletariat would never become revolutionary, and that the nation had to be the vehicle of development. An elementary implication of this position is that leftist-initiated strikes and violent confrontations are not merely irrelevant pranks but actual hindrances to progress.

When Mussolini founded Utopia, it was to provide a forum at which his Party comrades could exchange ideas with his friends the revolutionary syndicalists outside the Party. He signed his articles at this time "The Man Who Is Seeking." The collapse of the Second International on the outbreak of war, and the lining up of the mass socialist parties of Germany, France, and Austria behind their respective national governments, confirmed once again that the syndicalists had been right: proletarian internationalism was not a living force. The future, he concluded, lay with productionist national syndicalism, which with some tweaking would become Fascism.

Mussolini believed that Fascism was an international movement. He expected that both decadent bourgeois democracy and dogmatic Marxism-Leninism would everywhere give way to Fascism, that the twentieth century would be a century of Fascism. Like his leftist contemporaries, he underestimated the resilience of both democracy and free-market liberalism. But in substance Mussolini's prediction was fulfilled: most of the world's people in the second half of the twentieth century were ruled by governments which were closer in practice to Fascism than they were either to liberalism or to Marxism-Leninism.

The twentieth century was indeed the Fascist century.

But Fascism lived on.... "Most of the world's people in the second half of the twentieth century were ruled by governments which were closer in practice to Fascism than they were either to liberalism or to Marxism-Leninism."

This article first appeared in LIBERTY magazine. Their website can be found at http://www.libertysoft.com/liberty/index.html

Notes

1. Original words from the 1934 song by Cole Porter. They were amended later.(back)

2. At the Munich conference in 1938, Mussolini was the only person present who could follow all the discussions in the four languages employed.(back)

3. Amadeo Bordiga, Angelo Tasca, and Karl Liebknecht.(back)

4. Although Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria, support for the Central Powers in Italy was negligible.(back)

5. It remained Mussolini's paper through the Fascist period. At first it was described as a "Socialist Daily." Later this was changed to "The Daily of Fighters and Producers."(back)

6. It was first called the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Leagues), changing its name in 1921 to the National Fascist Party. Fasci is plural of fascio, a union or league. The word had been in common use for various local and ad hoc radical groups, mainly of the left.(back)

7. Of the seven who attended the preparatory meeting two days before the launch, five were former Marxists or syndicalists. Zeev Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 222. At the launch itself, the majority had a nationalist background.(back)

8. Garibaldi's followers had worn red shirts. Corradini's nationalists, absorbed into the Fascist Party in 1923, wore blue shirts.(back)

9. Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914-1945 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), p. 95.(back)

10. Ernest Jones, Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (New York: Basic Books, 1957), vol. 3, p. 180.(back)

11. Prior to 1938 the Fascist Party had substantial Jewish membership and support. There is no agreement among scholars on Mussolini's motives for introducing anti-Jewish legislation. For one well-argued view, see Gregor, Contemporary Radical Ideologies: Totalitarian Thought in the Twentieth Century (New York: Random House, 1968), pp. 149-159.(back)

12. Among numerous sources on the life of Mussolini, see Richard Collier, Duce! A Biography of Benito Mussolini (New York: Viking, 1971); Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1982); Jasper Ridley, Mussolini: A Biography (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998). All such works are out of their depth when they touch on Fascist ideas. For a superb account of all the fascist and other non-Communist dictatorial movements of the time, see Payne, History. On Mussolini's ideas, see A. James Gregor, Young Mussolini and the Intellectual Origins of Fascism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979); Sternhell, Birth, Chapter 5.(back)

13. It's now usual to capitalize 'Fascism' when it refers to the Italian movement, and not when the word refers to a broader cultural phenomenon including other political movements in other countries.(back)

14. Chicago has an avenue named after the brutal blackshirt leader and famous aviator, Italo Balbo, following his specatacular 1933 visit to the city. Chicago's Columbus Monument bears the words "This monument has seen the glory of the wings of Italy led by Italo Balbo." See Claudio G. Segrè, Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).(back)

15. The evolution of this incredible theory is mercilessly documented in Gregor, The Faces of Janus: Marxism and Fascism in the Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), chs. 2-5. For a good brief survey of interpretations of Fascism, see Payne, History, ch. 12. For a detailed examination, see Gregor, Interpretations of Fascism (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1997).(back)

16. Confronted with egregious high-handedness by authority, working-class Americans call it "Communism." Middle-class Americans, educated enough to understand that it's uncouth to say anything against Communism, call if "fascism."(back)

17. Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (New York: Macmillan, 1962).(back)

18. Richard N. Hunt, The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974), vol. I, p. xiii, and vols. I and II, passim.(back)

19. On Hendrik de Man, also known as Henri De Man, see Sternhell, Neither Right Nor Left: Fascist Ideology in France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986). Mussolini exchanged letters with de Man in which both tacitly recognized that de Man was following Mussolini's intellectual trajectory of 10-15 years earlier. Sternhell, Birth, p. 246. To this day there are disciples of de Man who treat his acceptance of the Third Reich as something like a seizure rather than as the culmination of his earlier thought, just as there are leftist admirers of Sorel who refuse to admit Sorel's pre-fascism.(back)

20. The most illuminating single work is Sternhell, Birth. Other important accounts are: Gregor, Young Mussolini; Gregor, Faces of Janus; Sternhell, Neither Right Nor Left; Payne, History. A useful collection of old and new readings is Roger Griffin, ed., International Fascism: Theories, Causes, and the New Consensus (London: Arnold, 1998). Important works in Italian include those of Renzo de Felice and Emilio Gentile.(back)

21. The Fascist government imposed measures which were intended to promote modernization. They were not necessary and their effectiveness was mixed. Italian output grew rapidly, but so it had in earlier years.(back)

22. Many would not yet have acknowledged that there was no falling rate of profit and no concentrating trend in industry, but all had to agree that these were proceeding far more slowly than earlier Marxists had expected.(back)

23. Before the 1890s, there was no more impeccable a Marxist than Bernstein. He had been a friend of Marx and Engels, who maintained a confidence in his ideological soundness that they placed in very few individuals. His 1899 book, known in English as Evolutionary Socialism (New York: Schocken, 1961), is put together from controversial articles he began publishing in 1896.(back)

24. The impact of anti-rationalism on socialism not only helped to form Fascism, but also had a broad influence on the left. Like Fascism, the thinking of leftist writers such as Aldous Huxley and George Orwell arises from the impact on nineteenth-century socialism of the fin de siècle offensive against rationalism, materialism, individualism, and romanticism.(back)

25. The strong influence of Sorel on the formation of Fascism has now been heavily documented. See, for example, Sternhell, Birth. In earlier years, some writers used to minimize this influence or deny Sorel's close affinity with Fascism.(back)

26. Sorel's was the old-fashioned kind of antisemitism, which always made room for some good Jews. Among these Sorel counted Henri Bergson. Sternhell, Birth, p. 86.(back)

27. It was also inferred from experience. It could be observed that if the one or two strongest personalities behind a strike were somehow neutralized, the strike would collapse.(back)

28. In What Is to Be Done?, Lenin maintained that the working class, left to itself, could develop only "trade union consciousness." To make the working class revolutionary required the intervention of "professional revolutionaries."(back)

29. See Gregor, Young Mussolini, ch. 4.(back)

30. The Crowd (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1995). The early nineteenth century had seen a fascination with hypnosis (then called Mesmerism). The late nineteenth century witnessed an extrapolation of the model of hypnosis onto wider human phenomena. Le Bon argued that, in groups, individuals become hypnotized and lose responsibility for their actions. Scholars, other than French ones, now believe that Le Bon was a dishonest self-promoter who successfully exaggerated his own originality, and that his claims about crowd behavior are mostly wrong. His influence was tremendous. Freud was steeped in Le Bon. The discussion of propaganda in Hitler's Mein Kampf, which strikes most readers as more entertaining than the rest of the book, echoes Le Bon.(back)

31. Gregor, Young Mussolini. This was precisely the view of many Communists in the early years of the Comintern. Payne, History, p. 126.(back)

32. Ludwig von Mises, Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War (New Rochelle: Arlington House, 1969 [1944]), pp. 55-58.(back)

33. "If by mysticism one intends the recognition of truth without the employment of reason, I would be the first to declare myself opposed to every mysticism." Mussolini, quoted in Gregor, Contemporary Radical Ideologies, p. 331.(back)

34. Mussolini was openly an atheist prior to 1922, when his conversion was staged for transparently political reasons. In addition to his many articles and speeches criticizing religion, Mussolini wrote a pamphlet, Man and Divinity, attacking the Church from a materialist standpoint and also wrote a strongly anti-Catholic book on Jan Hus, the fifteenth-century Czech victim of Catholic persecution. Until it became politically inexpedient, Mussolini gave a speech every year on the anniversary of the murder by the Church of the freethinker Giordano Bruno in 1600. In office, Mussolini worked with the Church, generally gave it what it wanted, and was rewarded with its enthusiastic endorsement.(back)

35. On Churchill's fulsome praise of Fascism throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, see Ridley, Mussolini, pp. 187-88, 230, 281. For Mises's more guarded praise in 1927, see Mises, The Free and Prosperous Commonwealth (Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1962), pp. 47-51.(back)

36. The Fascist government was appallingly oppressive compared with the democratic regime which preceded it, but distinctly less oppressive than Communism or National Socialism. Payne, History, pp. 121-23.(back)

37. Karl Marx, Speech on the Question of Free Trade. Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Collected Works (New York: International, 1976), vol. 6, pp. 450-465.(back)

38. The word "totalitarian" (totalitario) was first used against Fascism by a liberal opponent, Giovanni Amendola. It was then taken up proudly by Fascists to characterize their own form of state. Later the term was widely employed to refer to the common features of the Fascist, Soviet, and Nazi dictatorships or to denote an ideal type of unlimited government. In this sense, the word was in common use among Anglophone intellectuals by 1935, and in the popular media by 1941. Ironically, Fascist Italy was in practice much less "totalitarian" than the Soviet Union or the Third Reich, though the regime was methodically moving toward totalitarianism.(back)

39. On Gentile's ideas see Gregor, Phoenix: Fascism in Our Time (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1999), chs. 5-6.(back)

40. The most outstanding American scholar of Fascism is A. James Gregor. A shortcoming of Gregor's analysis is his tendency to assume that Fascist economic policy could work, that it is possible for a Fascist government to stimulate industrial growth. Any such view has to somehow come to terms with the fact that Italian economic growth was robust before World War I.(back)

41. "Liberal" means classical liberal or libertarian.(back)

42. Ignazio Silone held that Mussolini unscrupulously aimed only at power for himself. The School for Dictators (New York: Harper, 1939). While this is less preposterous than the theory that he sold out for financial gain, it too cannot be squared with the facts of Mussolini's life.(back)

43. Angelica Balabanoff, socialist activist and Mussolini's mistress intermittently from 1904 on, was in Lenin's entourage, shipped with him into Russia in the famous German "sealed train."(back)

44. Ridley, Mussolini, p. 67.(back)

45. Sternhell, Birth, p. 202.(back)

46. It may seem odd that there was such anxiety about Italian development when the Italian economy was growing quite lustily: precisely the same paradox arises with recent leftist attitudes to "poverty in the Third World."(back)

47. On the striking similarities between Fascism and African Socialism, see Gregor, Contemporary Radical Ideologies, Chapter 7.(back)

TOPICS: