Posted on 11/30/2025 6:05:42 PM PST by Red Badger

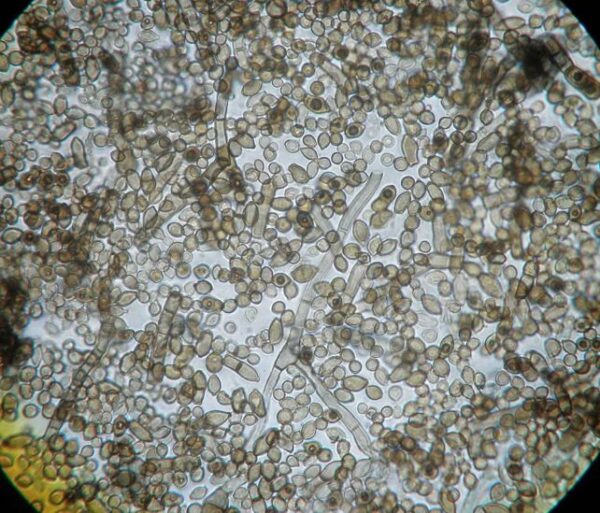

Cladosporium sphaerospermum, cultured at the Coimbra University Hospital Centre in Portugal. (Rui Tomé/Atlas of Mycology, used with permission) The Chernobyl exclusion zone may be off-limits to humans, but ever since the Unit Four reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded nearly 40 years ago, other forms of life have not only moved in but survived, adapted, and appeared to thrive.

Part of that may be the lack of humans… but for one organism, at least, the ionizing radiation lingering inside the reactor's surrounding structures may be an advantage.

There, clinging to the interior walls of one of the most radioactive buildings on Earth, scientists have found a strange black fungus curiously living its best life.

Related: Worms at Chernobyl Appear Mysteriously Unscathed by Radiation

That fungus is called Cladosporium sphaerospermum, and some scientists think its dark pigment – melanin – may allow it to harness ionizing radiation through a process similar to the way plants harness light for photosynthesis. This proposed mechanism is even referred to as radiosynthesis.

But here's the really funky thing about C. sphaerospermum: Although scientists have shown that the fungus flourishes in the presence of ionizing radiation, no one has been able to pin down how or why. Radiosynthesis is a theory, one that's difficult to prove.

The mystery began back in the late 1990s, when a team led by microbiologist Nelli Zhdanova of the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences embarked on a field survey in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone to find out what life, if any, could be found in the shelter surrounding the ruined reactor.

There, they were stunned to find a whole community of fungi, documenting an astonishing 37 species. Notably, these organisms tended to be dark-hued to black, rich with the pigment melanin.

C. sphaerospermum dominated the samples, while also demonstrating some of the highest levels of radioactive contamination.

As surprising as the discovery was, what happened next deepened the intrigue.

Radiopharmacologist Ekaterina Dadachova and immunologist Arturo Casadevall — both with posts at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the US – led a team of scientists that found exposing C. sphaerospermum to ionizing radiation doesn't harm the fungus the way it would other organisms.

Melanized C. sphaerospermum. (Rui Tomé/Atlas of Mycology, used with permission)

Ionizing radiation describes emissions of particles powerful enough to knock electrons from their atoms, turning them into their ionic forms.

That sounds pretty benign on paper, but in practice, ionization can break apart molecules, interfering with biochemical reactions and even shredding DNA. None of that is a good time for a human, although it can be exploited to destroy cancer cells, which are particularly vulnerable to its effects.

However, C. sphaerospermum seemed strangely resistant and even grew better when bathed in ionizing radiation. Other experiments showed ionizing radiation changed the behavior of fungal melanin – an intriguing observation that warranted further investigation.

The follow-up paper by Dadachova and Casadevall in 2008 is where they first proposed a biological pathway similar to photosynthesis.

The fungus – and others like it – appeared to be harvesting ionizing radiation and converting it into energy, with melanin performing a similar function to the light-absorbing pigment chlorophyll.

At the same time, the melanin behaves as a protective shield against the more harmful effects of that radiation.

C. sphaerospermum under the microscope. (Rui Tomé/Atlas of Mycology, used with permission)

This appears to be supported by the findings of a 2022 paper, in which scientists describe the results of taking C. sphaerospermum into space and strapping it to the exterior of the ISS, exposing it to the full brunt of cosmic radiation.

There, sensors placed beneath the petri dish showed that a smaller amount of radiation penetrated through the fungi than through an agar-only control.

The aim of that paper was not to demonstrate or investigate radiosynthesis, but to explore the fungus's potential as a radiation shield for space missions, which is a cool idea. But, as of that paper, we still don't know what the fungus is actually doing.

Scientists have been unable to demonstrate carbon fixation dependent on ionizing radiation, metabolic gain from ionizing radiation, or a defined energy-harvesting pathway.

"Actual radiosynthesis, however, remains to be shown, let alone the reduction of carbon compounds into forms with higher energy content or fixation of inorganic carbon driven by ionizing radiation," writes a team led by engineer Nils Averesch of Stanford University.

The idea of radiosynthesis is so cool – like something out of science fiction. But it's maybe even cooler that this weird fungus is doing something we don't understand to neutralize something so dangerous to humans.

It's not the only one, either. A black yeast, Wangiella dermatitidis, demonstrates enhanced growth under ionizing radiation. Meanwhile, another fungus species, Cladosporium cladosporioides, exhibits enhanced melanin production but not growth under gamma or UV radiation.

So the behavior observed in C. sphaerospermum is not universal to melanized fungi.

Does that suggest that it's an adaptation allowing the fungus to feast on powerful light that can kill other organisms? Or is it a stress response that enhances survival under extenuating, but not ideal, conditions?

At this point, it's impossible to tell.

What we do know is that this humble, velvety black fungus is doing something clever with ionizing radiation to survive and maybe even proliferate in a place too dangerous for humans to safely tread; that life does, indeed, find a way.

The Blob, Steve was supposed to be a teenager, driving a 54 Plymouth.

The Chernobyl accident is the biggest example of antinuke hysteria.

Only about 47 people died there.

The dangerous radiation dissipated within a year!

Except for few spots where the radioactive materials somehow congregated, the rest of the area is totally safe.

But we are still treated to articles like this!

The reactor is still in meltdown and will be for at least a hundred years. The concrete ‘sarcophagus’ will eventually deteriorate and the molten mass of uranium it contains will sink into the ground water table.................

I guess, our grand children may be worried about that.

I am sure, they will find a fix.

Right now, if I were in charge, I would go there, and map the radiation levels.

Fence off the reactor and the few places where there are demonstratively high levels of radiation and declare all the rest OK!

They have done that! There is an exclusion zone around Chernobyl of 30 kilometres (19 miles).

Chain-linked Fenced in and warning signs in multiple languages all around.

A couple of years back, an international team of scientists were allowed in to do surveys of the area and see what has happened to the wildlife.

They were dumbfounded!

There not only was plentiful wildlife, but it was thriving!

Every kind of wildlife, birds, rabbits, mice, moose, bear, fox and anything else you can imagine. Trees and plant life was fully recovered where the trees had all died.

Everything was radioactive way beyond what is considered to be safe and healthy exposure!

Why, they wondered?

Then it dawned on them:

All these things die of natural age-related things before the radiation has an affect that would kill them. They don’t live long enough for the radiation to become a problem.

Now, humans with a much longer lifespan would have a problem living there, but still might live to be 40-50 years..............

Nope,

The radioactive Iodine, which was by far the most radioactive element released, and was really the only dangerous product of the reactor has half time of 8 days.

It is gone a very long time ago, few before one year passed!

The radioactive cesium (not really that dangerous) has half time 30 years, so even this is mostly gone. There is some radioactive plutonium there with half time 12,000 years.

So

Is there some trace radioactivity attributable to the reactor accident? Answer is definitely YES!

Will there be some traces of radioactivity detectable in long future? Yes!

Does it matter for the human life and well being? NO!

The data, I have available, shows levels of radioactivity well below the safe levels in the vast majority of the exclusion zone!

Whole area is safe for short visits, but there are few small areas, where I would not go to live for long time.

Back of the reactor, basement of Pripyat hospital, cemetery, some stairs somewhere.

Most of it could be easily cleaned and/or fenced off.

The rest of the exclusion zone has levels which are completely safe for humans to stay. It should be declared safe and repopulated!

About 30 years ago!

For now and the near future it has become a huge college science project.......................

Because people have an unrealistic fear of radioactivity.

We are surrounded by it, we cannot hide from it, in low doses it is likely beneficial, but the media and lawyers are very hysterical about it.

Unfortunately!

So this is “The Last Of Us” then?

I hear they are making a sequel to that movie...............

Yes, I woke up this morning feeling Black after listening to Otis Redding for three hours last night.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTVjnBo96Ug

I suppose these days you just feel what you are according to the lights of the left, BUahahahahahahaha!

In addition to the fact there is no organic matter or plant life on Mars.

You’re probably right - but did any of us think life would thrive in an area like Chernobyl with that much radiation?

Are they edible?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.