Posted on 10/22/2021 8:32:19 AM PDT by Red Badger

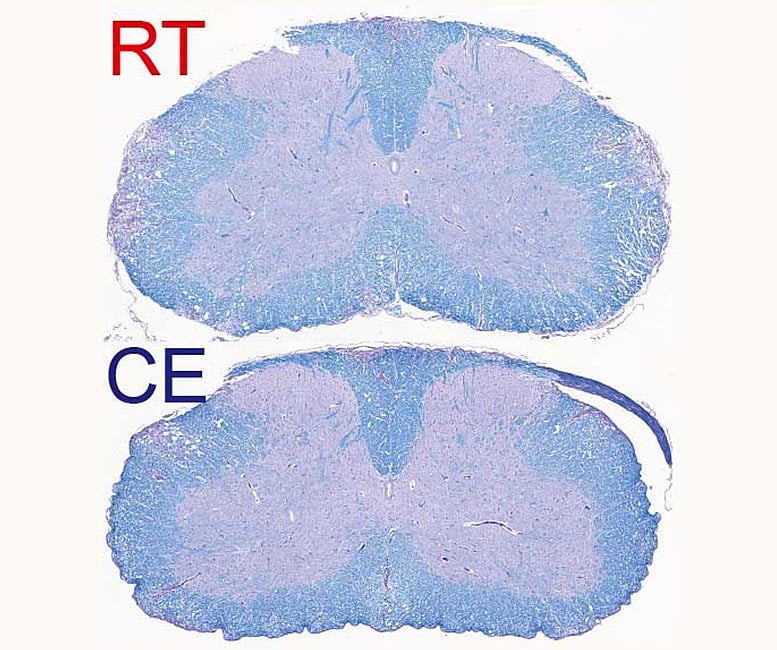

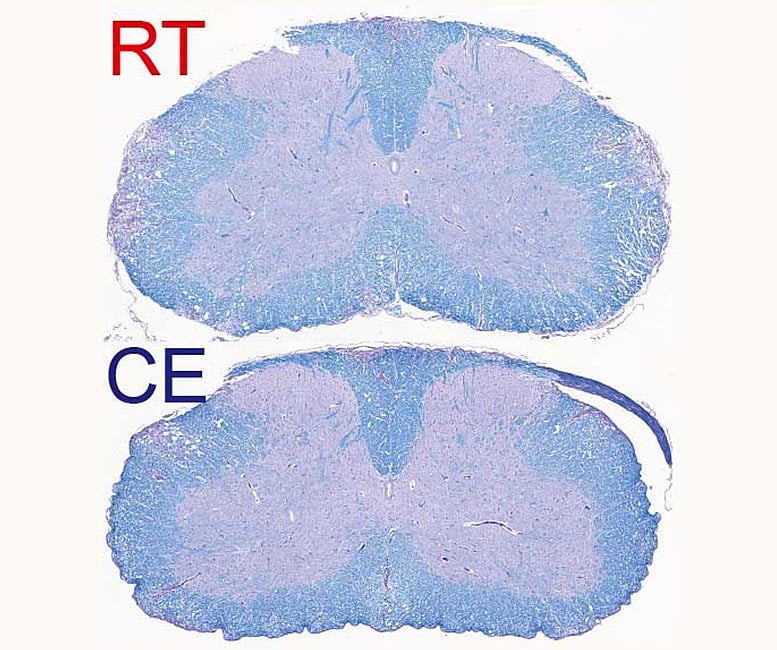

Demyelinated spinal cord of mice suffering from autoimmune disease. Top, at room temperature, and bottom, exposed to cold. Myelin is colored in blue. The purple staining within the white matter (parts towards the edge of the histological section) shows demyelinated lesions that are reduced in the bottom image. Credit: © UNIGE – Laboratoires Trajkovski & Merkler /Cell Metabolism

========================================================================================

Scientists at UNIGE are demonstrating how cold could alleviate the symptoms of multiple sclerosis by depriving the immune system of its energy.

In evolutionary biology, the “Life History Theory,” first proposed in the 1950s, postulates that when the environment is favorable, the resources used by any organism are devoted for growth and reproduction. Conversely, in a hostile environment, resources are transferred to so-called maintenance programs, such as energy conservation and defense against external attacks. Scientists at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) developed this idea to a specific field of medicine: the erroneous activation of the immune system that causes autoimmune diseases.

By studying mice suffering from a model of multiple sclerosis, the research team succeeded in deciphering how exposure to cold pushed the organism to divert its resources from the immune system towards maintaining body heat. Indeed, during cold, the immune system decreased its harmful activity which considerably attenuated the course of the autoimmune disease. These results, highlighted on the cover of the journal Cell Metabolism, pave the way for a fundamental biological concept on the allocation of energy resources.

Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system attacks the body own organs. Type 1 diabetes, for example, is caused by the erroneous destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic cells. Multiple sclerosis is the most common autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (consisting of the brain and spinal cord). The disease is characterized by the destruction of the myelin, which is a protective insulation of nerve cells and is important for the correct and fast transmission of electrical signals. Its destruction thus leads to neurological disability, including paralysis.

“The defense mechanisms of our body against the hostile environment are energetically expensive and can be constrained by trade-offs when several of those are activated. The organism may therefore have to prioritize resource allocation into different defense programs depending on their survival values,” explains Mirko Trajkovski, professor in the Department of Cellular Physiology and Metabolism and the Diabetes Centre at the Faculty of Medicine of the UNIGE, and lead author of the study. “We hypothesized that this can be of particular interest for autoimmunity, where introducing an additional energy-costly program may result in milder immune response and disease outcome. In other words, could we divert the energy expended by the body when the immune system goes awry?”

A drastic reduction in symptoms To test their hypothesis, the scientists placed mice suffering from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model of human multiple sclerosis, in a relatively colder living environment — about 10°C — following an acclimatization period of gradually decreasing the environmental temperature. “After a few days, we observed a clear improvement in the clinical severity of the disease as well as in the extent of demyelination observed in the central nervous system,” explains Doron Merkler, professor at the Department of Pathology and Immunology and the Centre for Inflammation Research at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine and co-corresponding author of the work. “The animals did not have any difficulty in maintaining their body temperature at a normal level, but, singularly, the symptoms of locomotor impairments dramatically decreased, from not being able to walk on their hind paws to only a slight paralysis of the tail.”

The immune response is based, among other things, on the ability of so-called antigen-presenting monocytes to instruct T cells how to recognize the “non-self” elements that must be fought. In autoimmune diseases, however, the antigens of the “self” are confused with those of the “non-self.” “We show that cold modulates the activity of inflammatory monocytes by decreasing their antigen presenting capacity, which rendered the T cells, a cell type with critical role in autoimmunity, less activated,” explains Mirko Trajkovski. By forcing the body to increase its metabolism to maintain body heat, cold takes resources away from the immune system. This leads to a decrease in harmful immune cells and therefore improves the symptoms of the disease.

“While the concept of prioritizing the thermogenic over the immune response is evidently protective against autoimmunity, it is worth noting that cold exposure increases susceptibility to certain infections. Thus, our work could be relevant not only for neuroinflammation, but also other immune-mediated or infectious diseases, which warrants further investigation,” adds Mirko Trajkovski.

Autoimmune diseases on the rise The improvement in living conditions in Western countries, which has been noticeable over the past decades, has gone hand in hand with an increase in cases of autoimmune diseases. “While this increase is undoubtedly multifactorial, the fact that we have an abundance of energy resources at our disposal may play an important but as yet poorly understood role in autoimmune disease development,” concludes Doron Merkler.

The researchers will now pursue their research to better understand whether their discovery could be developed in clinical applications.

Reference:

“Cold Exposure Protects from Neuroinflammation Through Immunologic Reprogramming” 22 October 2021, Cell Metabolism.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.10.002

Purpose: Recent evidence implicates the GI microbiota in the progression of neurological diseases such as Parkinsons Disease1, Multiple Sclerosis and Myasthenia Gravis2. We report three patients with MS diagnoses who achieved durable symptom reversal with FMT for constipation.

Methods: Case study observations on three MS cases Results: Case 1: A 30 yr old male with constipation, vertigo and impaired concentration and a concomitant history of MS and trigeminal neuralgia. Neurological symptoms included severe leg weakness and he required a wheelchair and an indwelling urinary catheter. Previous failed treatments included Mexiletine, Tryptanol and β-interferon.

The patient underwent 5 FMT infusions for his constipation, with its complete resolution. Interestingly his MS also progressively improved, regaining the ability to walk and facilitating the removal of his catheter. Initially seen as a ‘remission', the patient remains well 15 yrs post-FMT without relapse.

Case 2: A 29 yr old wheelchair-bound male with ‘atypical MS' diagnosis and severe, chronic constipation. He reported parasthesia and leg muscle weakness. The patient received 10 days of FMT infusions which resolved his constipation. He also noted progressive improvement in neurological symptoms, regaining the ability to walk following slow resolution of leg parasthesia. Three years on the patient maintains normal motor, urinary and GI function.

Case 3: An 80 yr old female presented with severe chronic constipation, proctalgia fugax and severe muscular weakness resulting in difficulty walking, diagnosed as ‘atypical' MS. She received 5 FMT infusions with rapid improvement of constipation and increased energy levels. At eight months she reported complete resolution of bowel symptoms and neurological improvement, now walking long distances unassisted. Two years post-FMT, the patient was asymptomatic.

Conclusion: We report reversal of major neurological symptoms in three patients after FMT for their underlying GI symptoms. As MS can follow a relapsing-remitting course, this unexpected discovery was not reported until considerable time had passed to confirm prolonged remission. It is tempting to speculate that FMT achieved eradication of an occult GI pathogen driving MS symptoms. Our finding that FMT can reverse MS-like symptoms suggests a GI infection underpinning these disorders. It is hoped that such serendipitous findings may encourage a new direction in neurological research.

A molecule widely assailed as the chief culprit in Alzheimer's disease unexpectedly reverses paralysis and inflammation in several distinct animal models of a different disorder — multiple sclerosis, Stanford University School of Medicine researchers have found.

This surprising discovery, which will be reported in a study to be published online Aug. 1 as the cover feature in Science Translational Medicine, comes on the heels of the recent failure of a large-scale clinical trial aimed at slowing the progression of Alzheimer's disease by attempting to clear the much-maligned molecule, known as A-beta, from Alzheimer's patients' bloodstreams. While the findings are not necessarily applicable to the study of A-beta's role in the pathology of that disease, they may point to promising new avenues of treatment for multiple sclerosis.

The short protein snippet, or peptide, called A-beta (or beta-amyloid) is quite possibly the single most despised substance in all of brain research. It comes mainly in two versions differing slightly in their length and biochemical properties. A-beta is the chief component of the amyloid plaques that accumulate in the brains of Alzheimer's patients and serve as an identifying hallmark of the neurodegenerative disorder.

A-beta deposits also build up during the normal aging process and after brain injury. Concentrations of the peptide, along with those of the precursor protein from which it is carved, are found in multiple-sclerosis lesions as well, said Lawrence Steinman, MD, the new study's senior author. In a lab dish, A-beta is injurious to many types of cells. And when it is administered directly to the brain, A-beta is highly inflammatory.

Yet little is known about the physiological role A-beta actually plays in Alzheimer's — or in MS, said Steinman, a professor of neurology and neurological sciences and of pediatrics and a noted multiple-sclerosis researcher. He, first author Jacqueline Grant, PhD, and their colleagues set out to determine that role in the latter disease. (Grant was a graduate student in Steinman's group when the work was done.)

Previous research by Steinman, who is also the George A. Zimmerman Professor, and others showed that both A-beta and its precursor protein are found in MS lesions. In fact, the presence of these molecules along an axon's myelinated coating is an excellent marker of damage there. Given the peptide's nefarious reputation, Steinman and his associates figured that A-beta was probably involved in some foul play with respect to MS. To find out, they relied on a mouse model that mimics several features of multiple sclerosis — including the autoimmune attack on myelinated sections of the brain that causes MS.

Steinman had, some years ago, employed just such a mouse model in research that ultimately led to the development of natalizumab (marketed as Tysabri), a highly potent MS drug. That early work proved that dialing down the activation and proliferation of immune cells located outside the central nervous system (which is what natalizumab does) could prevent those cells from infiltrating and damaging nerve cells in the CNS.

Knowing that immunological events outside the brain can have such an effect within it, the Stanford scientists were keen on seeing what would happen when they administered A-beta by injecting it into a mouse's belly, rather than directly to the brain. "We figured it would make it worse," Steinman said.

Surprisingly, the opposite happened. In mice whose immune systems had been "trained" to attack myelin, which typically results in paralysis, A-beta injections delivered before the onset of symptoms prevented or delayed the onset of paralysis. Even when the injections were given after the onset of symptoms, they significantly lessened the severity of, and in some cases reversed, the mice's paralysis. Steinman asked Grant to repeat the experiment. She did, and got the same results.

His team then conducted similar experiments using a different mouse model: As before, they primed the mice's immune cells to attack myelin. But rather than test the effects of A-beta administration, the researchers harvested the immune cells about 10 days later, transferred them by injection to another group of mice that did not receive A-beta and then analyzed this latter group's response.

The results mirrored those of the first set of experiments, proving that A-beta's moderating influence on the debilitating symptoms of the MS-like syndrome has nothing to do with A-beta's action within the brain itself, but instead is due to its effect on immune cells before they penetrate the brain.

Sophisticated laboratory tests showed that A-beta countered not only visible symptoms such as paralysis, but also the increase in certain inflammatory molecules that characterizes multiple-sclerosis flare-ups. "This is the first time A-beta has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties," said Steinman.

Inspection of the central nervous systems of the mice with the MS-resembling syndrome showed fewer MS-like lesions in the brains and spinal cords of treated mice than in those not given A-beta. There was also no sign of increased Alzheimer's-like plaques in the A-beta-treated animals. "We weren't giving the mice Alzheimer's disease" by injecting A-beta into their bellies, said Grant.

In addition, using an advanced cell-sorting method called flow cytometry, the investigators showed A-beta's strong effects on the immune system composition outside the brain. The numbers of immune cells called B cells were significantly diminished, while those of two other immune-cell subsets — myeloid cells and memory T-helper cells — increased. "

At this point we wanted to find out what would happen if we tried pushing A-beta levels down instead of up," Grant said. The researchers conducted a different set of experiments, this time in mice that lacked the gene for A-beta's precursor protein, so that they could produce neither the precursor nor A-beta. These mice, when treated with myelin-sensitized immune cells to induce the MS-like state, developed exacerbated symptoms and died faster and more frequently than normal mice who underwent the same regimen. Lennart Mucke, MD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease in San Francisco and a veteran Alzheimer's researcher, noted that while A-beta's toxicity within the brain has been established beyond reasonable doubt, many substances made in the body can have vastly different functions under different circumstances. "

A-beta is made throughout our bodies all of the time. But even though it's been studied for decades, its normal function remains to be identified," said Mucke, who is familiar with Steinman's study but wasn't involved in it. "Most intriguing, to me, is this peptide's potential role in modulating immune activity outside the brain."

The fact that the protection apparently conferred by A-beta in the mouse model of multiple sclerosis doesn't require its delivery to the brain but, rather, can be attributed to its immune-suppressing effect in the body's peripheral tissues is likewise intriguing, suggested Steinman. "There probably is a multiple-sclerosis drug in all this somewhere down the line," he said.

Journal reference: Science Translational Medicine Provided by Stanford University Medical Center.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.