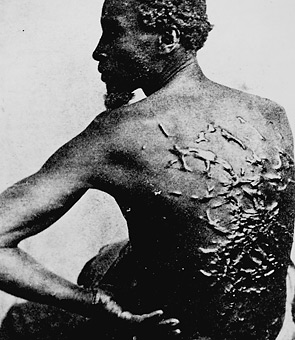

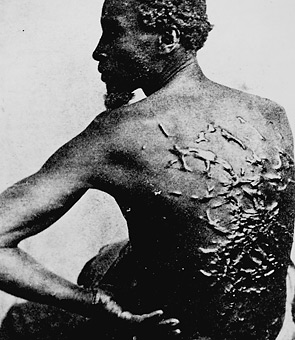

I could as well - as long as you also carve this gentleman's image on Stone Mountain.

Posted on 01/24/2014 8:00:53 AM PST by rockrr

It seems fitting that the de facto anthem of the Confederacy during the Civil War, which some people might still be shocked to learn the North won, turned out to be "Dixie."

After all, since Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox there's been no shortage of looking away, looking away at the reality of history when it comes to the Civil War.

Nowhere is that full flower of denial more apparent than among the followers of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which is upset about a proposal to erect a monument to Union soldiers who died in the Battle of Olustee, regarded by historians as the largest and deadliest engagement in Florida during the "wowrah." Related News/Archive

Next month marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Olustee, about 45 miles west of Jacksonville. Some 2,000 Union troops died in the conflict, while 1,000 Confederate soldiers also perished in an engagement that did not substantially alter the course of the Civil War.

The 3-acre Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park includes three monuments honoring the Confederate troops who fought and died in the encounter. But when the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War pushed for a memorial on the site to pay homage to the sacrifices of their forbearers, hostilities ensued. So did illiterate silliness.

(Excerpt) Read more at tampabay.com ...

You despise the “southron slavrocracy” but honor the brave soldiers that fought on behalf of it?

Irrelevant

Yes

Curiosity.

And forgive my confusions about the destruction of steel mills rather than warehouses and railroad infrastructure.

The point is that the Confederates wrecked military and infrastructure targets, not farms, villages and towns in their path as Sherman did. That even included the Early raid on Chambersburg in 1864 as the only political target which Early's cavalry went out of their way to destroy was the home of prominent abolitionist newspaper editor. Quite the contrast to Sherman's army who went after everything, including the homes of widows and orphans.

That being said, my original comments were fully supportive of union monuments on battlefields in the south as I pointed our that there were no shortage of confederate monuments on this side of the Mason-Dixon line.

Slave prices were said to average up to $500 in 1860, which depending on how you look at that, could be anything from $100,000 to over $1,000,000 in today's values.

Times four million slaves equals about 20% of the total asset value of the United States in 1860.

So, the fact is that by 1860, average white Deep South families were considerably better off than their northern cousins.

One reason is: for over 50 years the value, price and productivity of their slaves had steadily increased, with very positive effects on both the income-statements and balance-sheets of slave owners.

Demand for slave produced goods -- sugar, tobacco, rice & especially cotton -- grew exponentially with rising prices making slavery the most profitable industry in the United States.

As an asset class, slaves represented the single largest investment in the United States -- more than railroads & manufacturing combined.

That's why the Deep South especially was determined to defend slavery against any and all threats -- whether real or imagined.

Indeed, the Slave-Power well understood that in order to maintain the asset value of its "property", slavery must be not only protected, it must constantly expand into new territories, countries & products.

That's why the "Black Republicans'" promise of no slavery in the territories represented a real threat to the Slave Power.

In 1864, Early first demanded the city of Chambersburg hand over $500,000.

In today's values, depending on how you look at it, that is anywhere from $100 million to $1 billion.

When the city refused, Early burned it down.

So please explain: in what way was Early's behavior in August 1864 different from, or superior to, that of WT Sherman a few months later?

So, you're OK with Confederates burning down towns, murdering civilians (i.e., Lawrence Kansas), etc., just not Union troops, right?

So, how do you feel about allied bombings of Axis powers in WWII?

Quantrill, who led the murdering in Lawrence, Kansas, was officially disavowed by the C.S.A. command. As you are probably aware, Jesse James and other later infamous outlaws served under Quantrill who used the template of war to steal and murder.

There's no evidence suggesting that when Confederate General McCausland, under orders from Jubal Early, burned down Chambersburg on July 30, 1864, that his actions were in any way not sanctioned by Confederate high command.

The truth of this matter is that we have a long list of Confederate invasions, raids and guerilla actions in Union states and territories.

Antietam/Sharpsburg & Gettysburg were only the largest of these, but there were many more, and eventually included, without exception, every Union state and territory near the Confederacy, and some quite far removed.

When Confederate forces invaded Union lands, again without exception, they took what they considered legitimate "contraband" (i.e., food, horses), and destroyed what they thought might be of value militarily (i.e., railroads).

Yes, on rare occasion they pretended to "pay for" their seizures, but only with Confederate money, which eventually became worthless.

The burning of Chambersburg, PA -- 2/3 of the city according to this source, $1.6 million in property (circa $300 million in today's values), leaving 2,000 citizens homeless, according to this source -- Chambersburg was their largest destruction of civilian property, but it strongly suggests that Confederates were as fully capable as Union forces of massive destruction, when they believed it necessary.

Therefore, the fact that Confederate destruction of Union lands was not as extensive as Union destruction of Confederate lands simply tells us that Confederates had less ability, and less opportunity to wreck havoc.

So the moral issue here is precisely the same as that of bombing civilian targets during World War Two.

Both sides did it, indeed the enemy started it, but the allied side eventually did more, and it helped them win Unconditional Surrender, and therefore now three generations of peace.

So, are we to condemn allied bombing for the lives it took, while ignoring the much larger numbers who would have died had victory been delayed by months or even years?

The Civil War was more complicated. Yes, the south started things by firing on Ft. Sumter. A measured response would've been a sea blockade or dispatching a marine contingent to retake the fort; not a full scale land invasion of Virginia, which hadn't even joined the CSA until it became clear that they were the main target of the full scale invasion.

Yeah, the burning of Chambersburg was a nasty affair, but it in no way even compared to the scale of what Sherman's army did to Georgia. And, yeah, the ability of the respective armies to visit destruction on enemy territory has some validity unless you consider the relatively benign invasion of Pennsylvania by Lee's army in the month prior to Gettysburg. I will discount the equally relatively benign invasion of Maryland by Lee's army in the month prior to Antietam/Sharpsburg the previous year, given that the entertained hopes of enlisting Maryland into the C.S.A. cause or at least ensuring her neutrality.

They had no such illusions about Pennsylvania in June of 1863. Granted that the war took a far nastier turn post Gettysburg which saw the end of prisoner exchanges, furloughs, etc. But we still have a compare and contrast to what course invading armies took when they HAD the ability to visit massive destruction on the locals: Lee's army in Maryland in August/September of 1862 and Lee's army in Pennsylvania in June of 1863 vs. Sherman's army in Georgia, 1864 and Butler's army in Louisiana and Mississippi in 1862-63.

FRiend, I don't blame you, I blame our woeful education system for it's failures to teach even basic facts of history.

In this particular case "a measured response" is precisely what Lincoln first proposed after Fort Sumter, on April 15, 1861:

On April 19, Lincoln called for a blockade of Confederate ports.

The Confederacy responded by:

All of this happened before a single Confederate soldier was killed directly in battle with any Union force, or before any Union force "invaded" a single Confederate state.

Indeed, the first Union "invasion" didn't happen until after Virginians voted to secede, and join the Confederacy's formally declared war on the United States.

The first actual battle deaths came on June 10, 1861.

Vigilanteman: "Yeah, the burning of Chambersburg was a nasty affair, but it in no way even compared to the scale of what Sherman's army did to Georgia."

But, it happened before Sherman's "March to the Sea", and it was not the Confederates' only atrocity against civilians.

The fact is, in general, Confederates did more damage to civilians than Union troops, for the very simple reason that Confederate supplies were much less reliable, and therefore, they had to "live off the land" much more.

By contrast, Union troops normally received plentiful supplies from nearby railheads.

The exception of Sherman's "march to the sea" is especially notable precisely because it was such an exception.

Vigilanteman: "...the relatively benign invasion of Pennsylvania by Lee's army in the month prior to Gettysburg."

Yeh, right...

People often forget that one major reason Lee lost at Gettysburg was: his "eyes and ears", JEB Stuart's cavalry, were out gallivanting across Maryland and Pennsylvania, scarfing up all the food, horses and wagon-loads of other supplies they could carry.

So Stuart wasn't there to help Lee figure out where the Union Army was moving, resulting in some poor decisions by Lee.

However "relatively benign" you may think that, the fact is Stuart considered those supplies essential, and his pursuit of them cost Lee the battle, and arguably, the Confederacy the war.

Vigilanteman: "...we still have a compare and contrast to what course invading armies took when they HAD the ability to visit massive destruction on the locals: Lee's army in Maryland..."

Of course, you make the wrong comparisons.

The correct comparison to Sherman in Georgia, November 1864, is not Lee in Maryland, 1862, but rather Jubal Early's burning of Chambersburg in July 1864.

The correct comparison to "Beast" Butler in 1862-63 Louisiana/Mississippi is not Lee at Gettysburg in 1863, but rather the Bee Creek Massacre of December 1861, and Champ Ferguson in Eastern Tennessee, all through 1861 to 1864, including the Saltville Massacre in Virginia, October 1864.

In short: sure, you can always make a case by choosing the "best of Confederates" compared to the "worst of Unionists", but if you compare apples-to-apples, the truth of the matter is that they come out about the same.

And let us, please, give credit where it is due: by comparison to almost any other armies in civil or other wars throughout the history of mankind, our ancestors on both sides were veritable models of "Christian soldiers", and deserve to be recognized as such.

. . . by comparison to almost any other armies in civil or other wars throughout the history of mankind, our ancestors on both sides were veritable models of "Christian soldiers", and deserve to be recognized as such.

Amen to that. If you want to study a real nasty civil war, the one going on now in Syria or the Thirty Years War in Europe would prove just how true that statement is.

Lee only compares to Grant.

Sherman & Butler do compare to lower ranking Confederates like Early & Stuart.

Indeed, if you think about it: Sherman under Grant at Vicksburg took on some general similarity to Stuart under Lee at Gettysburg.

And great website, by the way.

As you probably know, neither Lee nor Grant were the top commanders of their respective forces until near the end of the war. They got there due to their leadership and results.

Grant's promotion, as I recall, did not come until near the end of the Wilderness Campaign in 1864. Lee's maybe just a few months earlier.

Until then, they were outranked by men of far lesser ability.

Joe, I think your numbers are a bit off.

What cost $500 in 1860 would cost $12592.47 in 2012.

Source: http://www.westegg.com/inflation/infl.cgi

Even if he’s off by 100%, you’re not anywhere near a million dollars.

You are correct, if we only look at the Consumer Price Index.

The problem is: that gives a less-than-accurate picture of relative dollar values.

Better comparisons would include the question -- comparing average unskilled workers' wages in 1860 to today, how much does $500 equal?

The answer is, approximately $89,000.

And there are several other reasonable comparisons.

Here is one list:

Based on these, I picked nice round numbers, saying $500 in 1860 could equal anything from $100,000 to $1,000,000 in today's values.

Here's one way to look at it: in 1860 with $500 you could buy a farm of 100 to 150 acres.

That same farm today would cost you from circa $500,000 to $1.5 million.

Or consider: an investment of $500 in 1850 was roughly equivalent to buying a very nice house today.

I could as well - as long as you also carve this gentleman's image on Stone Mountain.

I realize that. The practice of human slavery by blacks was morally abhorrent, as was the practice of human slavery by whites. It's morally abhorrent where practiced today.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.