Posted on 02/04/2012 5:09:12 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

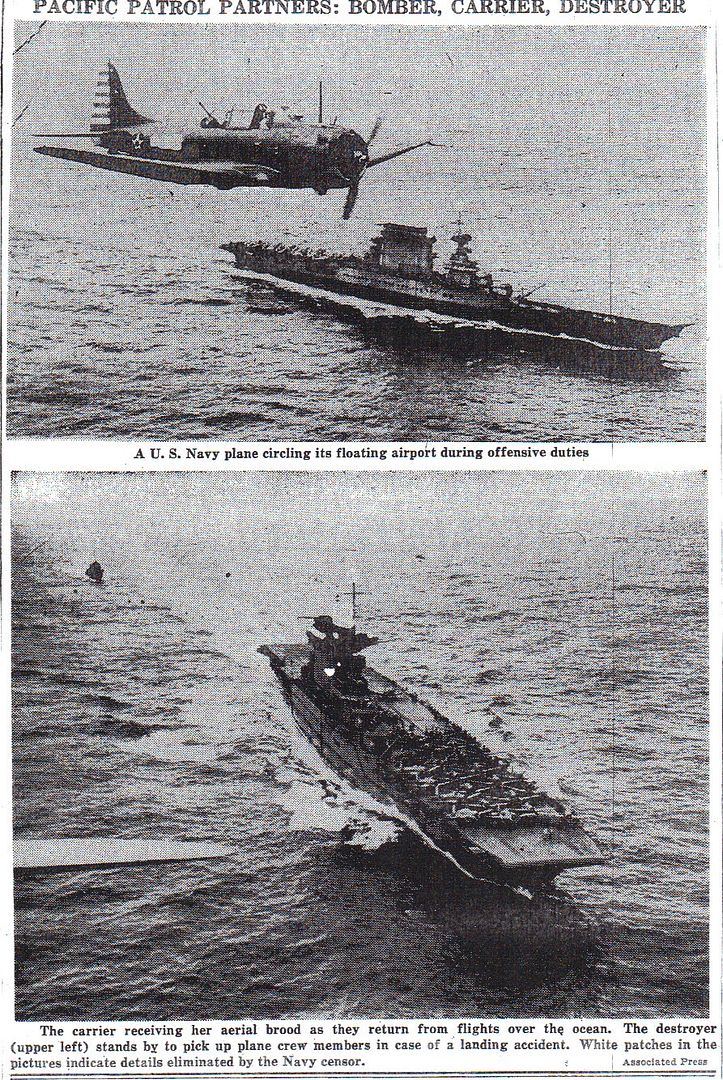

* Which carrier? What type of plane? What did the censor white out? Extra credit – which destroyer is trailing?

Good morning Homer. THX for the post.

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1942/feb42/f04feb42.htm

Japanese planes strike Allied warships

Wednesday, February 4, 1942 www.onwar.com

In the Dutch East Indies... Dutch and American ships attacking in the Makassar Straits are repelled by Japanese aircraft. Two American cruisers are damaged in the fighting.

In Malaya... Japan demands the surrender of Singapore. British authorities there refuse. General Wavell continues to bring in reinforcements despite the overwhelming odds against success in battle against the Japanese. Wavell wants the island to hold while Allied forces elsewhere in the East Indies are being strengthened.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/04.htm

February 4th, 1942

UNITED KINGDOM: Canadian press baron Max Beaverbrook is appointed Britain’s Minister of Production. His steamrolling determination as Minister of Aircraft Production has already resulted in Britain producing more fighters than Germany. (Jack McKillop)

Minesweeper HMS Dornoch launched.

Minesweeping trawlers HMS Ruskholm and Hunda launched.

Destroyer HMS Pakenham commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

GERMANY: U-258 commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

NORTH AFRICA: As the British dig in on the Gazala/Bir Hacheim line and Rommel contemplates his next move, grave doubts surround the future of the Eighth Army commander, Lt-Gen Neil Ritchie. One popular commander, Lt-Gen A. R. Godwin-Austen, has resigned and General Auchinleck, has ordered Major-Gen Eric Dorman-Smith to sound out senior officers in secret. Auchinleck and Dorman-Smith picnicked today in the desert - where they could talk freely. The major-general said that Ritchie was “not sufficiently quickwitted or imaginative”. But Auchinleck - who has already sacked one commander - decided that Ritchie should stay. “To sack another would affect morale,” he said.

EGYPT: Cairo: The British ambassador to Egypt, Sir Miles Lampson, presses King Farouk to appoint a pro-Allied government by surrounding his palace with tanks.

LIBYA: 13 Corps, British Eighth Army, completes a withdrawal to the line Gazala-Bir Hacheim and is fortifying it while Axis forces hold the line Tmimi-Mechili. A lull ensues until summer during which both sides conduct harassing operations and prepare to renew the offensive. The British gradually relieve battle-weary forces with fresh troops as they become available. (Jack McKillop)

JAPAN: Tokyo: Japan demands the surrender of Singapore.

SINGAPORE ISLAND: The Japanese demand the surrender of the Allied forces. The government refuses. (Jack McKillop)

Tengah Airfield is abandoned after intense shelling and bombing by the Japanese. (Jack McKillop)

AUSTRALIA: The USAAF Far East Air Force’s 7th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 9th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), and 88th Reconnaissance Squadron (Heavy) begin a movement from Brisbane, Queensland, to Karachi, India. The 9th is operating from Jogjakarta, Java with B-17s; the 88th is operating from Hickam Field, Territory of Hawaii with B-17s. (Jack McKillop)

JAVA SEA: Japanese reconnaissance flying boats of the Toko Kokutai (Naval Air Corps) contact and shadow the allied force (Rear Admiral Karel W.F.M. Doorman, RNN) of four cruisers and accompanying destroyers, sighted yesterday by 1st Kokutai aircraft, attempting the transit of Madoera Strait to attack the Japanese Borneo invasion fleet. The Allied fleet is now south of the Greater Sunda Islands, about 190 miles (306 kilometres) east of Surabaya, Java. On the strength of that intelligence, Japanese naval land attack planes of the Takao, Kanoya, and 1st Kokutais bomb Doorman’s ships, damaging the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) and light cruiser USS Marblehead (CL-12). Dutch light cruisers HNMS De Ruyter and HNMS Tromp are slightly damaged by near-misses. USS Marblehead’s extensive damage (only by masterful seamanship and heroic effort does she reach Tjilatjap, Java, after the battle) results in her being sent back to the United States via Ceylon and South Africa; despite the loss of turret III (one-third of her main battery), USS Houston, however, remains. (Jack McKillop)

NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES: The small Australian garrison on Ambon Island, largely the 2/21 Battalion, surrenders to the Japanese. What followed the surrender of the Australians has become known as “The Carnage at Laha.” Up to 100 of the allied prisoners were seriously wounded or ill at the time of surrender and died shortly after. According to Japanese accounts ten men were summarily executed after falling into Japanese hands during the attacks, another 20 to 40 Australians were held at Suakodo for a few days then executed between the 6 and 8 February. These unfortunate POWs (ca. 30 Australian POWs), said a Japanese Warrant Officer after the war, were led one by one away from the native school and a little way along the road into the jungle near Laha with their hands tied behind their back. Lieutenant NAKAGAWA Ken-ichi, the head executor made each kneel down with a bandage over his eyes. The Japanese troops then stepped out of ranks to behead each POW or bayonet him one by one. Each Australian was decapitated by a sword blow to the neck severing the head, death was almost instantaneous, and carried out by about ten samurai wielding Japanese having despatched two or three prisoners. The remaining Australians at Laha perished over the next two weeks, once the dead had been burned and the battleground debris cleared by the captives. (Jack McKillop)

PACIFIC OCEAN: Asiatic Fleet (Admiral Thomas C. Hart) ceases to exist. Units of Asiatic Fleet are organized into Naval Forces, Southwest Pacific Area under Vice Admiral William A. Glassford. (Jack McKillop)

COMMONWEALTH OF THE PHILIPPINES: HQ US Army Forces, Far East (USAFFE) takes direct control of the Panay and Mindoro garrisons, which were previously part of the Visayan-Mindoro Force, established early in January under command of Brigadier General William F. Sharp. (Jack McKillop)

On Bataan, the II Corps front is relatively quiet. In the I Corps area, the Japanese in Big Pocket repel still another tank-infantry attack. In the South Sector, Philippine Scouts and tanks continue their attack against Canaan Point and this time succeed in compressing the Japanese into a small area at the tip. In the Anyasan-Silaiim sector, tank-infantry attacks against the Japanese still make slow progress. (Jack McKillop)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: USS Branch (DD-197), which was commissioned as HMS Beverley (H-64) on 8 Oct, 1940, part of the destroyers-for-bases deal, today attacks and sinks U-187. (Ron Babuka)

An unarmed U.S. tanker is torpedoed, shelled, and sunk by German submarine U-103 about 20 miles (32 kilometres) southeast of Cape May, New Jersey. (Jack McKillop)

SS Montrolite (11,309 GRT) Canadian Imperial Oil tanker is torpedoed and sunk NE of Bermuda, in position 35.14N, 060.05W, by U-109, Kptlt Heinrich ‘Ajax’ Bleichrodt, Knight’s Cross, Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, CO. Of her crew of 48, there are 20 survivors. They were rescued by a passing freighter and were landed in Halifax. Montrolite had been travelling alone from Venezuela and was carrying a cargo of crude oil. Canada had a fleet of only twelve nationally flagged tankers in 1939. They were, for the most part, large and modern vessels, quite unlike the dry cargo fleet. In 1940, Canada imported 43 million tons of crude oil and five million tons of refined fuel products, 50 percent of which was brought in by tanker through the St. Lawrence River and Atlantic ports. By the summer of 1942, three of these tankers had been lost to German U-boats, leaving only three Canadian and five chartered Norwegian tankers to serve the East Coast. These losses had a nearly catastrophic impact of the supply of naval fuel oils. By Mar 42, St. John’s was down to 3,000 tons (three days’ supply). A month later, the supply at Halifax was down to 45,000 tons (15 days’ supply). The two small coastal tankers used to supply St. John’s were run in separate convoys for fear of loosing them both, which would have forced the termination of operations by the Mid-Ocean Escort Force. The gravity of the situation can be appreciated by comparing the supply levels at Halifax and St. John’s with the carrying capacity of a ‘notional tanker’ (10,000 tons of cargo moved at 10 knots). The loss of even one more tanker could have had far-reaching operational and tactical consequences. In May 42, the US transferred twelve tankers to Canada totalling 106,000 GRT (approximately 170,000 DWT), which allowed the chartered Norwegian tankers to be released for the transatlantic route. At the same time, the US transferred 40 tankers to British control, declared an ‘Unlimited National Emergency’, and instituted petroleum rationing. In Sep 42, another 34 tankers were transferred to British control. These were the last tankers that could be taken up from US trade until emergency production ships began to arrive in 1943. The charter fees for all loaned American tankers were paid by the US. U-109 was a long-range Type IX U-boat built by AG Weser, at Bremen. Commissioned 05 Dec 40. U-109 completed eight patrols and compiled a record of 14 ships sunk for a total of 86,606 tons and one ship damaged for a further 6,548 tons. U-109 was sunk on 04 May 43, south of Ireland, in position 47-22N, 022-40W, by 4 depth charges from a Liberator a/c from RAF 86 Sqn. All of U-109’s crew of 52 was lost. Heinrich Bleichrodt was born in 1909, at Berga, Kyffhauser. He joined the navy in 1933 and after service in the cadet ship Gorch Fock and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, transferred to the U-boat force in Oct 39. He took command of U-48 on 08 Sep 40, at the age of 30. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross on 24 Oct 40 (the 18th awarded in the U-boat force) and on 23 Sep 42 was awarded the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross (the 17th in the Kriegsmarine and 15th in the U-boat force). His First Watch Officer was ‘Teddy’ Suhren, ultimately a winner of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. Together they sank eight ships for a total of 36,189 tons. Upon learning that he had been awarded a Knight’s Cross, Bleichrodt refused to wear it until Suhren had received one as well, as he had been in charge of all surface firings. Thus, on 03 Nov 40, Suhren became the first Watch Officer to receive the Knight’s Cross. In Dec 40, Bleichrodt left U-48 and in Jan 41, commissioned U-67. In Jun 41, he took command of U-109. In total, ‘Ajax’ Bleichrodt sank 27 ships for a total of 158,957 tons and damaged three ships for a further 16,362 tons in only eight patrols, making him the 10th highest scoring U-boat ace. He left U-109 in Jul 43 to become a tactical instructor with 2nd U-boat training division. From Jul 44 to the end of the war, he was the Commander of the 22nd U-boat Flotilla. Heinrich Bleichrodt died on 09 Jan 77 in Munich, Germany. (Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.A.: Attorney General Francis Biddle orders Japanese, German and Italian aliens to leave 31 areas in the states of Washington and Oregon by 15 February. (Jack McKillop)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: MS Silveray torpedoed and sunk by U-751 at 43.54N, 64.16W. (Dave Shirlaw)

Assuming that it is a actual WW-II photo and not from a prewar training exercise, the carrier is the USS Lexington CV-2, a Douglas SBD Dauntless, the censored areas are most likely radar and radio equipment.

The Sartoga in Februaru of 42 was laid up after stopping a Jap torpedo opn January 11, 1942:-(

No clue on the DD, Yet :-)

Regards

alfa6 ;>}

The article about Eleanor Roosevelt blaming the American people for the debacle at Pearl Harbor is priceless and deserves a thread of its own.

Interesting article on farm labor camps for aliens and fear of arsenic poisoning by Japanese farmers.

That must be late in 42 as the Sara did not get out of Bemerton till almost the end of May.

Notice to that the two turrets fore and aft of the island look to be 5”38cal mounts. After stopping the Jap torpedo in January the Sara made it to Pearl for temporary repairs. the 6” turrets were removed to be used as shore batteries around Pearl Harbor.

BTW, Nice see ya again:-)

Regards

alfa6 ;>}

"DAMN this snow!"

"Damn this whole country!"

The howling gale drowned the men's curses and carried them away into nothingness. Visibility was barely ten paces. For the past twenty-four hours an Arctic blizzard had been sweeping over the tundra, whipping fine powdered snow through the air and turning the half-light of the Arctic winter day into an icy inferno. They could feel the gale on their skins. They could feel it stinging their eyes like needles. It felt as if it was going right into their brains.

Hans Riederer stumbled. His rucksack rode up to the back of his neck. Was the gale mocking him?

In long single file they were trudging through the powdered snow, which did not get compressed under their boots, but slipped away like flour, offering no footholds. Suddenly, like a ghost, a heavily swathed sentry appeared in front of the marching column. He directed the company over to the right, down a small track branching off the Arctic Ocean road. First Lieutenant Eichhorn was now able to make out the outlines of the bridge over the Petsamojoki, the bridge leading to the fighting-line, into the tundra, to the sector they were taking over.

"Half right!" the lieutenant shouted behind him.

The Jägers passed it on. The long file swung over to the right, to the edge of the road by the ramp of the bridge. A column was coming over from the far side. Men heavily wrapped up. Most of them had beards. They were leaning over forward as they marched, weighed down by their heavy burdens.

"Who are you?"they called out over the storm.

"6th Mountain Division—come to relieve you,"Eichhorn's men replied.

The men on the bridge gave a tired wave. "

"Haven't you come from Greece?"

"Yes."

"God, what a swap for you!" And on they moved.

The fragments of a few curses were drowned by the blizzard. Like ghosts the men moved past Eichhorn's company. Then came four walking casualties, the dressings on their faces heavily encrusted, their hands in thick bandages. Immediately behind them six men were hauling an akja, a reindeer sledge. On it was a long bundle tied up in tarpaulin.

They stopped, beating their arms round their bodies. "Do you belong to the 6th?"

"Yes. And you?"

"138th Jäger Regiment."

That meant they were part of 3rd Mountain Division. The lance-corporal in front of the sledge noticed the officer's epaulettes on Eichhorn's greatcoat. He brought his hand to his cap and ordered his men: "Carry on!"

They moved on. On the sledge, trussed up in the sheet of tarpaulin, was their lieutenant. He had been killed five days before.

"He must have a proper grave," the lance-corporal had said.

"We can't leave him here in this damned wilderness."

So they had carried him down from the hill where they had been entrenched—down granite-strewn slopes, then through moss and past the five stunted birches to the first fir-tree. That was where their akja stood. They had now been hauling him for four hours. They had another two hours to go before they reached Parkkina with its military cemetery.

The date was 9th October. The day before they had finished their "Prince Eugene" bridge over the Petsamojoki. They had barely driven in the last nail before the Arctic blizzard began. It marked the beginning of the Arctic winter. Fifty hours later all transport to the front came to a standstill. The Arctic Ocean road was blocked by snowdrifts, and the newly built tracks in the forward area had vanished under deep snow. In the forward lines the battalions of 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions had been waiting for the past ten days for their relief, for supplies, for ammunition and mail—also for a little tobacco and perhaps even a flask of brandy.

But ever since 28th September supplies had been getting through only in small driblets. This was due to a strange mishap which, in the afternoon of 28th September, completely destroyed the 100-yard-long wooden bridge over the Petsamojoki at Parkkina.

A few Soviet bombs had dropped on the river-bank just below the bridge. A few minutes later, as if pushed by some invisible giant hand, the whole bank had begun to move. About 4,000,000 cubic yards of soil started slipping. The 500-yardwide shelf between river and Arctic Ocean road fell into the river-valley over a length of some 800 yards. Entire patches of birch-woods were pushed into the riverbed. The waters of the Petsamojoki, a fair-sized river, piled up, overspilt their bank, and flooded the Arctic Ocean road. The bridge at Parkkina was crushed by the masses of earth as if it were built of matchsticks. Telephone-poles along the road were snapped and, together with the wires, disappeared in the landslide. Abruptly the entire landscape was changed. Worst of all, connection with the front across the river was severed. Urgent messages were sent to headquarters. There the officers gazed anxiously at the Arctic Ocean road, the lifeline of the front. Was it really cut?

What had happened?

Had the Russians been up to some gigantic devilry? Nothing of the sort : the Soviets had just been very lucky. The landslide by the Petsamojoki was due to a curious geological phenomenon

The river had carved its 25- to 30-feet-deep bed into a soft layer of clay which at one time had been sea-floor and therefore consisted of marine sediment. Following the raising of this layer through geological forces, these deposits hung along both sides of the river as a 500-yard-wide shelf of clay between the masses of granite. When the half-dozen 500-lb. bombs—aimed at the bridge— hit the bank, one next to the other, the soft ground lost its adhesion and developed a huge crack almost 1000 yards long. The adjacent strata pressed on it, and like a gigantic bulldozer pushed the mass of earth into the river-valley, which was about 25 feet deep and 160 yards wide.

There is no other recorded case in military history of supplies for an entire front of two divisions being interrupted in so curious and dramatic a fashion. Suddenly 10,000 to 15,000 men, as well as 7000 horses and mules, were cut off from all rearward communications.

Major-General Schörner immediately made all units and headquarters staff of his 6th Mountain Division already in the area available for coping with this natural disaster. Sappers dug wide channels through the masses of earth which had slipped into the river-bed to allow the blocked water to flow away. In twelve hours of ceaseless night work, jointly with the headquarters personnel, supply drivers, and emergency units, they built a double foot-bridge from both banks. Columns of porters were organized; parties of a hundred men at a time, relieved every two hours, carried foodstuffs, fodder, ammunition, fuel, building materials, and charcoal from hurriedly organized stores on the western bank across to the eastern bank. They shifted 150 tons a day.

Simultaneously, the sappers of 6th Mountain Division started building a new bridge. Up there, on the edge of the world, even the construction of a bridge was an undertaking of almost unimaginable difficulty and hazard. For that new bridge at Parkkina the men of Mountain Engineers Battalion 91 had to get their heavy beams from a newly setup sawmill 125 miles away. The lighter planks were brought by ship from Kirkenes to Petsamo. Some 25,000 lengths of round timber were picked up by the sappers from the timber store of the nickel-mines.

Meanwhile the battalions of the 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions were in the front line, unrelieved and without adequate food-supplies. Would they be able to hold out?

Would it be possible under such conditions to hang on to the forward winter positions? The battalions, which had been in -action there since June, were exhausted and bled white. The men were finished, physically as well as psychologically. With a heavy heart the German High Command therefore decided to withdraw the two divisions from the front and replace them by Major-General Schörner's reinforced 6th Mountain Division. At the time the decision was taken Schörner's men from Innsbruck were still in Greece. In the spring of 1941 they had burst through the "Metaxas Line," overcome Greek resistance along the Mount Olympus range, stormed Larissa in conjunction with the Viennese 2nd Panzer Division, taken Athens, and finally fought in Crete.

These men had then been switched from the Mediterranean to the extreme north, into the winter positions in the Litsa bridgehead. In the autumn of 1941 Schörner's Austrian Mountain Jägers would have been more than welcome before Leningrad or Moscow. The fact that Hitler dispatched them not to these sectors, but to the northernmost corner of the Eastern Front, proves the German Command's determination not to yield an inch of ground outside Murmansk.

On that sector there could be, there must be, no retreat. The enormous volume of American aid to the Soviet Union, which had since begun flowing, lent Murmansk new and vital importance.

Whereas at the beginning of the war Hitler had viewed the capture of Murmansk merely as the elimination of a threat to the vital ore-mines and the Arctic Ocean road, it was now a case of seizing a port of vital importance to the outcome of the war, and the railway-line serving that port. The German starting-line, the springboard for a new offensive against Murmansk, must therefore be held.

On 8th October the new bridge at Parkkina was finished— two days ahead of schedule. It was named the " Prince Eugene Bridge," after Eugene of Savoy, as a tribute to the Austrian Mountain troops who made up the bulk of General Dietl's Mountain Corps.

Long columns of supply vehicles had been held up on the Arctic Ocean road for weeks. Now they could start moving again. But it seemed as if there was a jinx on that sector of the front. Winter came surprisingly early—as, indeed, everywhere else on the Eastern Front. Only up there it started with a frightful Arctic gale. By the evening of 9th October all movement to the front had come to a standstill. Drivers who tried to defy the weather and get their lorries through were buried under snowdrifts and suffocated by their exhaust gases. Columns of porters lost their way and froze to death. Even the reindeer refused to budge. First Lieutenant Eichhorn's Company was stuck in front of the bridge.

In the front line the failure of supplies to arrive had terrible consequences. The men were starved, they were cold, and they were out of ammunition. The condition of the wounded was frightful. There were not enough bearers to take them out of the line quickly. Horses and mules were also badly affected. Major Hess, the Quartermaster of the Mountain Corps Norway, reports in his book Arctic Ocean Front, 1941 that the draught horses of 388th Infantry Regiment and those of 1st Battalion, 214th Artillery Regiment, in particular, were not up to the hardships. Within a few weeks 1400 horses died. Of the small Greek mules brought by Schorner's newly arrived division not a single one survived the hell of the tundra.

Nevertheless the Litsa front held out. The Austrian Jägers stood up to the Arctic winter, which hit their front eight weeks earlier than it did the divisions before Moscow. At long last their relief came. The companies of Schorner's 6th Mountain Division, which had taken over from 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions at the end of October, moved into the positions in the Litsa bridgehead and along the Titovka.

To hand over this difficult sector of the front, right up in the polar night, to a unit which had only just come from the sunny south and had no idea about living and fighting conditions in the extreme north was one of the most risky experiments of the whole war. In long columns, moving in single file, the companies trudged through the snow between the lakes and up on to the granite plateau. The snow was a foot deep. The temperature was already 10 degrees below zero. Near the front the men encountered heavily wrapped figures —NCOs detailed to take the new units to their positions. There was much waving of arms and subdued shouting. Careful there—the Russians are only a few hundred yards farther on. Now and again a Russian flare rose into the air and a few bursts of machine-gun fire swept over the ground.

"Follow me!"

Behind the NCOs the platoons moved off in different directions, and presently split up into sections. Thus the whole marching column vanished into nothingness. Where were they being taken?

Lance-corporal Sailer, with eight men from Innsbruck, was trudging through the snow behind his guide. "Where the hell is that man taking us?" he muttered.

The guide merely grunted and a moment later stopped. "Here we are."

A massive granite boulder with a machine-gun on top. Behind it a few miserable caves made from piled-up stones, lined with moss and roofed over with pine-branches, with smaller stones on top and a frozen tarpaulin over the entrance. These were their fighting positions and living quarters for the winter.

The Jägers were speechless. No dug-out, no pill-box, no trench, no continuous front line. And their cave was not high enough for a man to stand upright, but only just big enough for the men to cower close to one another. That was the winter line in the Litsa bridgehead.

That then was journey's end. They had come from sundrenched Athens, from the Acropolis, from the market-place of humanity; they had driven right across Europe, sailed through the Gulf of Bothnia and marched along the 400 miles of Arctic Ocean road from Rovaniemi.

Others had come by ship up the coast of Northern Norway, until the British had caught them off Hammerfest and chased them into the fjords. From there they had marched to Kirkenes, along road No. 50, foot-slogging it for over 300 miles. And now they were in the tundra before Murmansk, swallowed up by the polar night. With a few whispered words of advice the emaciated figures of 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions handed over to them.

"You're sure to get some material for living quarters and better dug-outs," they comforted them.

Then they packed their rucksacks and with a sigh of relief moved off, into the night. Many of them, especially the battalions of 3rd Mountain Division, went back along the same long road, the Arctic Ocean road south to Rovaniemi, which their comrades of the 6th had travelled in the opposite direction. Only the reinforced 139th Mountain Jäger Regiment remained behind in the area of Mountain Corps Norway, as an Army reserve. Thus it was spared the nightmarish journey along the Arctic Ocean road to the south. For by then winter had started in earnest and the trek to Southern Lapland was torture. The Arctic Ocean road was the lifeline of the fighting front. All traffic moving away from the front had to give way to traffic moving up. As a result, only one battalion moved south each day, always with predetermined destinations and bivouacs. Everything moved on foot: only the baggage went by vehicle. The guns, taken to pieces, infantry weapons, and ammunition stayed with the marching men and horses.

General Klatt, then Lieutenant-Colonel Klatt and in command of 138th Mountain Jäger Regiment, gives the following account of this trek in the divisional records of 3rd Mountain Division:

"Once we had reached the tree-line the worst was over. Now at last each day ended at a blazing camp-fire. These were a great help also to our emaciated animals, the first of which began to collapse after about ten days. What was to be done? We lifted their shivering bodies off the ground, collected enough wood to light a fire, and supported the animal's weakened flanks until it was warm again and could stand on its own feet. If it then returned to its accustomed place among the other animals we knew that we had outwitted death this time. We succeeded quite often, but by no means always, and it was invariably touch and go-a matter of a few minutes - whether we could save our dumb, shaggy friends."

Beyond Ivalot came the first Lapp settlements, and then Finnish farmhouses. The soldiers down from the Arctic saw the first electric light again, children playing, reindeer sleighs, and the Rovaniemi railway. A last forced march, and the Gulf of Bothnia came into sight. They had reached their objective.

The 24th anniversary of the Socialist October Revolution —which, under the Gregorian calendar since introduced, falls on 7th November—was marked in Moscow by the German assault on the capital. The Soviet metropolis was starving and shivering. Marauders roamed the streets. Special courts were sitting. The 8th and 9th November had been declared ordinary working days, in view of the situation. Only on the 7th were short celebrations to be held. The traditional mass rally of the Moscow City Soviet on the eve of the anniversary had been transferred below ground: at the lowest level of the Mayakovskiy station of the Moscow Metro, Stalin addressed the Party and the Red Army. He invoked victory and demanded loyalty and obedience. In the morning of 7th November military formations on their way to the front inched across the snow-covered Red Square, past Stalin. Stalin was standing on top of the Lenin Mausoleum—where later his own embalmed body was to lie for seven years—and saluted the Army units which were trudging in silence through the falling snow. All round the square countless AA guns had been emplaced for fear of a German air-raid. But Goering's Luftwaffe did not show up.

Some 1600 miles away from Moscow, on the icy front before Murmansk, the commander of the Soviet 10th Rifle Division decided to mark the 24th anniversary of the Revolution in a very special way: he wanted to make Stalin a present of a victory.

During the night of 6th/7th November Corporal Andreas Brandner in strongpoint K3 put his hand to his ear. The easterly wind was carrying across the noise of singing and hilarious revelry. From the Soviet positions the strains of the Internationale wafted across time and again. The corporal made a "special incident" report to Company. The company commander telephoned Battalion. Suspicion and caution were called for: when the Russians had vodka to drink it usually boded nothing good.

Were they merely celebrating, or was this the prelude to an attack?

By 0400 hours the men knew the answer: the Soviets were coming. With shouts of "Urra" a regiment charged against K3, and another against K4. The Siberians fought fanatically. They got inside the German artillery barrage. They gained a foothold on two unoccupied commanding heights immediately in front of the German positions. By immediate counter-attacks the Russians were dislodged —except from one conical rock in front of K3. There an assault party and hand-grenade battle was fought for the next few weeks, a kind of operation typical of this sector. It was reminiscent of the assault-party operations at Verdun and in the Dolomites during the First World War.

The Siberians were established under cover of an overhanging slab just below the summit of the rock, in the dead angle barely 10 yards below the German defenders. It was impossible to get at them with small arms or artillery. The handgrenade was the only effective weapon in the circumstances. Time and again, like cats, the Siberians would scramble up the overhang on their side and appear right in front of the small German strongpoint. They would fire their sub-machine-guns and charge the defenders. There would be hand-to-hand fighting, with rifle-butt, trenching-tool, and bayonet.

This kind of fighting continued for five days. The outcrop of granite was soon known as "hand-grenade rock." The men of 2nd Battalion, 143rd Jäger Regiment, climbing up on the German side to relieve their colleagues, would ask themselves anxiously: Shall I be walking down again on my own two feet, or shall I be carried on a stretcher?

During that short period the German defenders threw 5000 hand-grenades and the Russians left 350 killed in front of their lines.

After that the period of hibernation set in also on the Litsa bridgehead until mid-December 1941. Similarly, at the neck of the Rybachiy Peninsula, where the Machine-gun Battalions 13 and 14, as well as companies of the 388th Infantry Regiment, 214th Infantry Division, were in position, nothing much happened. The Arctic winter, now at its height, did not permit any major operations. The snow was lying many feet deep, and an icy blizzard swept over rocks and through the valleys. Only patrols kept the war alive. The German troops cut down the telegraph-poles of the Russian line to Murmansk and burnt them in the simple stoves which had since arrived. The Russians retaliated by attacks on sentries and columns of porters.

On 21st December, three days before Christmas Eve, the Soviet winter offensive which had been in full swing on the main front for the past fortnight opened also in the extreme north. The Soviet 10th Rifle Division, since promoted to Guards status for its attacks on the Revolution anniversary, as well as the 3rd and 12th Naval Brigades, once more charged against K3, and presently also against K4 and K5. That was on the sector of 143rd Jäger Regiment. Its sister regiment, the 141st Jägers, holding the southern part of the bridgehead, was not at first affected by the attacks, and could thus be drawn upon for counter-attacks to clear up enemy penetrations. One regiment of the Soviet 12th Naval Brigade which had broken through the German lines was pounced upon and routed by the 3rd Battalion, 143rd Jäger Regiment, which had been held in reserve, in a counter-attack launched in hard frost and a blinding blizzard on Hill 263.5. Those who escaped ran straight into the fire of the German artillery.

Along the Arctic Ocean Stalin's winter offensive did not gain an inch of ground. This failure of an attack mounted by numerically superior, superbly equipped, and winter-trained troops proved that the terrain and climate represented an almost insuperable obstacle to any attacker faced by a determined opponent. But Stalin was no more willing to accept this fact than Hitler. The danger threatening his Murmansk lifeline seemed too great to him. Its severance would have been a fatal blow to the entire Soviet war effort. By employing all available forces Stalin therefore tried to eliminate that threat and annihilate the German Mountain Corps. No price could be too high provided only Murmansk was held.

In the battle of Kiev in the autumn of 1941, the greatest German battle of encirclement in the Eastern campaign, the German Armies, after weeks of fighting, captured or destroyed, approximately 900 tanks, 3000 guns, and about 10,000 to 15,000 motor vehicles. In the subsequent battle of the Vyazma and Bryansk pockets, the greatest battle of annihilation in the Eastern campaign, the Soviets lost 1250 tanks. That was when Hitler authorized his Reich Press Chief to announce that "the enemy will never recover from this blow."

In fact, the American armament supplies during 1942 almost completely made good the material losses of the Red Army. The decisive effect of American aid on the destinies of the war could not be revealed more clearly than by this fact. The Western Powers soon discovered how to protect their convoys against the German U-boats in the Arctic Ocean and the German aircraft operating from airfields in Northern Norway and Northern Finland. Powerful naval forces would escort the huge convoys of thirty, forty, or even more merchant-ships right into Murmansk or into the White Sea. But they paid a heavy price for that lesson by the disaster which befell convoy PQ 17.

This famous convoy, at the same time, was a warning to the German High Command of the colossal volume of American aid that was being shipped to Russia's northern ports. In that sense PQ 17 was an important milestone in the war— for both sides.

Early in July 1942 a convoy of thirty-three transports, twenty-two of them American, steamed into the Northern Ocean. Almost the same number of naval units—cruisers, destroyers, corvettes, anti-aircraft vessels, submarines, and minesweepers —escorted the merchant armada, which was sailing in close order; its distant cover was provided by the British Home Fleet, with two battleships, one aircraft carrier, two cruisers, and fourteen destroyers.

On 4th July, as the convoy rounded Jan Mayen Island to turn into the Barents Sea, the British Admiralty in London received an urgent signal from an agent:

"German surface units-the battleship Tirpitz, the armored cruiser Admiral Scheer, and the heavy cruiser Hipper, as well as seven destroyers and three torpedo-boats-have put to sea from Altenfjord in Northern Norway."

That could only mean a full-scale attack on PQ 17 with greatly superior forces. The Home Fleet was too far away to arrive at the spot in time. The escort units were therefore ordered to take evasive action and order the convoy to disperse. The merchantmen were to try to reach their destination singly. That decision was a fatal mistake.

The German High Seas Fleet had no intention of attacking PQ 17; indeed, fearing enemy aircraft carriers, the units presently returned to port.

The scattered convoy, however, abandoned by its shepherds, was presently attacked by Admiral Donitz's pack of U-boats and by bomber squadrons and torpedo aircraft under the "Air Chief Kirkenes," and in a dramatic battle lasting several days utterly destroyed. Twenty-four transports and rescue vessels were sunk. The true weight of this blow can be judged only if one knows what lay in the holds of the sunken transports.

War material lost included 3350 motor vehicles, 430 tanks, 210 aircraft, and 100,000 tons of other cargo. That was the equivalent of the booty taken in a medium-sized battle of annihilation, like the one of Uman. The Allies learnt their lesson from this disaster. Never again did they send out their convoys without maximum cover by naval units and aircraft carriers. The result was that of 16.5 million tons of total American supplies dispatched to the Soviet Union 15 million tons reached their destination —most of it via Murmansk. These supplies included 13,000 tanks, 135,000 machine-guns, 100 million yards of uniform cloth, and 11 million pairs of Army boots.

But to return to the fighting for Murmansk. Towards the end of April 1942, after a lull of several months, Lieutenant-General Frolov, the C-in-C of the Soviet "Karelian Front," mounted his large-scale offensive with his Fourteenth Army. This offensive was intended to be decisive and to annihilate the German Mountain Corps which had been under the command of Lieutenant-General Schörner since January 1942. By means of a boldly conceived combined land and naval operation the Soviets wanted to crush the 6th Mountain Division in a big two-pronged pincer operation, reach Kirkenes and the ore-mines, and occupy Northern Finland.

The prelude was a frontal attack by the Soviet 10th Guards and 14th Rifle Divisions in the Litsa bridgehead. Concentrated artillery-fire, followed by a charge: at 0300 hours, in the milky light of the polar night, the Russians attacked in unending waves. At first they came in silence, then with shouts of "Urra."

Pounded by heavy shell-fire, smothered by a blizzard reducing visibility to a bare 10 yards, the men of the Austrian 143rd and 141st Jäger Regiments stood in their strongpoints, without yielding an inch. Whenever the Russians succeeded in penetrating the machine-gun and carbine fire and breaking into a strongpoint, they were overcome in hand-to-hand fighting. For three days the Soviet 14th and 10th Divisions ran amok—then their strength was spent. They had not gained an inch of ground. But General Frolov did not give up. He had another trump card. On 1st May six ski brigades, including the famous 31st Reindeer Brigade, circumvented the southern wing of the German line of strongpoints and made an enveloping attack against the rear of the 6th Mountain Division. Simultaneously the replenished and reinforced Soviet 12th Naval Brigade with 10,000 to 12,000 men landed on the western coast of Motovskiy Bay. Under cover of gunfire by Soviet torpedo-boats the naval infantry—or marines— charged ashore, burst through the weak German covering line held by only two companies, and drove on against the Parkkina-Zapadnaya Litsa supply route. "Revenge for 28th December" was their slogan. And it looked as though they would get it.

The situation was extremely critical. General Schörner personally brought up rearward units, supply formations, and headquarters personnel to the threatened supply route. There he flung himself down alongside his Jägers, firing his carbine, directing the counter-attacks, and ceaselessly urging his men: "Hold on! We've got to gain time!"

He succeeded.

Enough time was gained for the hurriedly summoned battalions of 2nd Mountain Division to be brought up from Kirkenes. On 3rd May, just before midnight, they moved into action—units of 136th and 143rd Jäger Regiments. The heavy, costly fighting continued until 10th May, when General Frolov's marines were forced to withdraw. The Soviet naval units in Motovskiy Bay evacuated the remnants. The Soviet northern prong had been smashed.

The southern prong, with the 31st Reindeer Brigade at its centre, encountered the picket lines of 139th Jäger Regiment, along the Titovka river. The strongpoints of these experienced troops, who had been through the fighting for Narvik, held out. But the Soviets seeped through the front and with their reindeer formations threatened the Arctic Ocean road, the airfield, and the nickel-mines.

Schörner mounted a successful counterblow. Battalions of 137th and 141st Jäger Regiments, together with a mixed combat group of Reconnaissance Detachment 112 and Engineers Battalion 91, halted the attack and smashed the enemy. But the Soviet High Command had another card up its sleeve—a dangerous card at that. But it was prevented from playing it. The fortunes of war intervened in Schemer's favor in a most terrible way.

Along the entirely unprotected southern flank of the German front, in the worst wilderness of the tundra, General Frolov had employed the Soviet 155th Rifle Division. It was to have given the German Mountain Corps its coup de grâce. But the Russians too were extended to capacity. The 155th Division had not received their winter equipment in time. By entire companies the Red Army men froze to death in the tundra. Under vast heaps of snow, along the lines of their advance, they lay dead and buried. It was an appalling repetition of Napoleon's tragedy: of 6000 Russians only 500 reached the combat zone. They were so emaciated that the smallest German picket groups were able to smash them.

But in spite of all defensive successes the general balance-sheet of the campaign in the Far North was shattering. For lack of strength three offensive wedges of the German-Finnish Armies had ground to a standstill in the vastnesses between Finland's eastern frontier and the Murmansk railway. The offensive of the Mountain Corps Norway had come to a halt in the bridgehead east of the Litsa. General Feige's XXXVI Army Corps succeeded in taking Salla, in smashing the Soviet XLVI Corps, and in capturing the high ground of Voytya and Lysaya. But after that its offensive vigor was likewise spent. The front of the Finnish III Corps under General Siilasvuo seized up west of Ukhta in a bridgehead east of the narrow neck of land between Lakes Topozero and Pya. The great objective, the Murmansk railway, though within arm's reach, was never attained.

One question inevitably arises: if it was impossible to seize Russia's vital lifeline from the Arctic Ocean to the Leningrad and Moscow fronts, why on earth were not the railway, the bridges, and the Murmansk transhipment installations put out of action by air-raids?

The answer can be found in the records of the German Luftwaffe Command, and it is significant of the war in the East as a whole. The Luftwaffe was able to score only partial successes. Any prolonged interruption of the railway or extensive destruction of engineering works and power stations proved impossible. Why? Simply because the Luftwaffe lacked adequate forces. The Fifth Air Fleet operating on the Northern Front was being dissipated by the need to support too many operations at the same time: hence it was unable to make any concentrated major effort that might have promised success. The fronts in the Far North had frozen rigid. Murmansk, the objective of the campaign, had not been reached. And Archangel, the finishing-point laid down in the plan for the war in the East, was a long way off.

SHARP SENATE TALK OVER PEARL HARBOR.

According to the story:

"Sharp debate arose in the Seante today on assessing the responsibility for Pearl Harbor."

Debate grew out of a denial by Senator Truman of charges by popular radio and newspaper columnist Walter Winchell (who also happened to be a Lieutenant Commander in the Naval Reserve) that:

Senator Wheeler blocked passage of a wire-tapping bill which, if enacted, might have led to knowledge of alleged Japanese plots against Hawaii and consequent defense against the Pearl Harbor attack... Legalized wire-tapping would have permitted discovery of Japanese plans against Pearl Harbor.

__________________________________________________

A devastating sneak attack against America, a wire-tapping bill, an opinionated radio personality...

Things sure were crazy 70 years ago, weren't they?

Well there’s the first mention of a general other than MacArthur coming out of a Philippine communique. Even if it is a short blurb at the end of the report.

Thanks for the pic Lancey and a lift of the alfa6 lid for your Dad’s service.

Wiki entry for the USS Leonard F. Mason

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Leonard_F._Mason_(DD-852)

Regards

alfa6 ;>}

Thanks for the link!

I didn’t know that one of the two Gemini astronauts the Mason retrieved was Neil Armstrong.

Cool stuff. (Yes, I am way old enough to remember the days of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo.)

I got to agree with alfa6 that the ship is the Lexington. The configuration of the bridge and the two decks on the aft of the exhaust tower is what leads me to think that. The Lexington had the two deck guns forward of the bridge at least back in October of 1941. By the Battle of the Coral Sea they are no longer present from what I can tell from photographs of the ship.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.