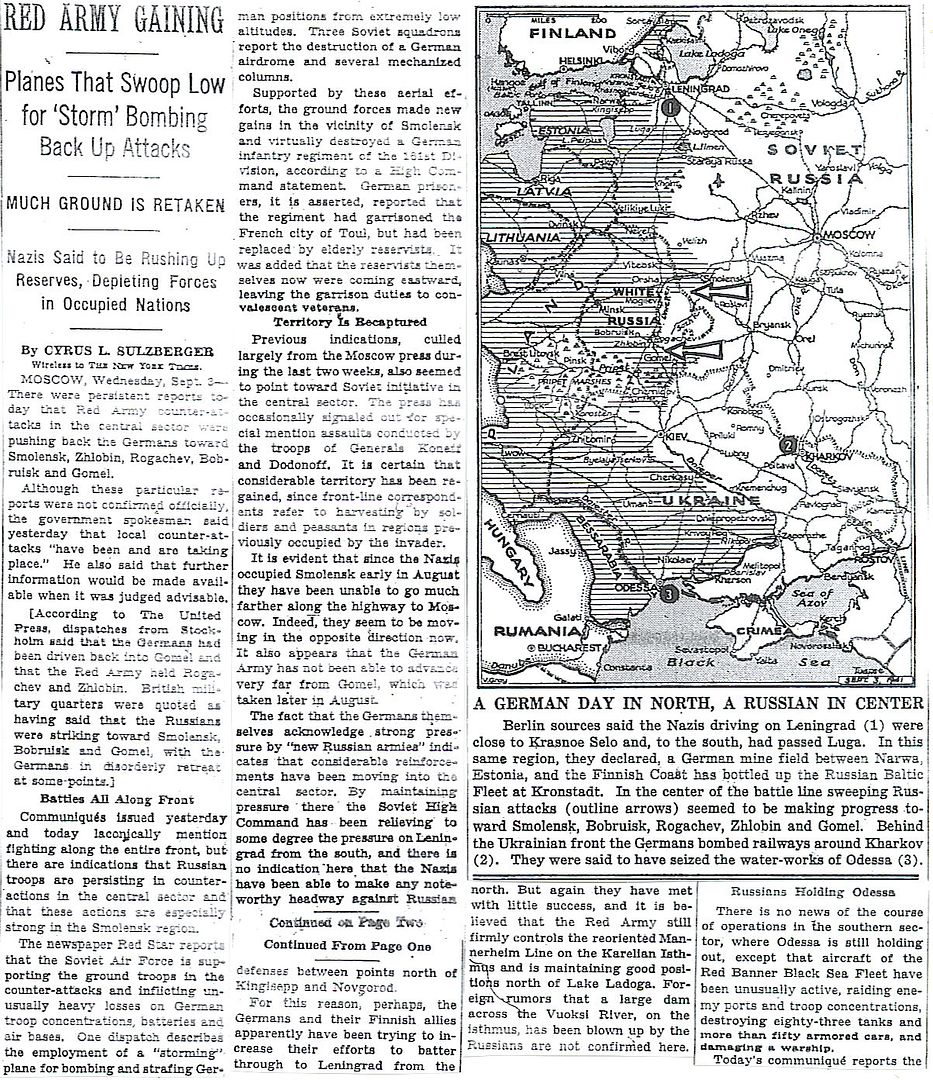

Posted on 09/03/2011 4:41:32 AM PDT by Homer_J_Simpson

John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1941/sep41/f03sep41.htm

Royal Navy planes hit Tromso

Wednesday, September 3, 1941 www.onwar.com

In Norway... The British carrier Victorious sends air attacks against German installations in and around Tromso but little damage is done.

In Tokyo... The Japanese are informed that a meeting between Prince Konoye and President Roosevelt cannot take place.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/03.htm

September 3rd, 1941

GERMANY: U-225 is laid down. U-593 and U-594 are launched. U-702 is commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

NORWAY: SPITZBERGEN: An Allied task force has robbed the Nazis of their most northerly asset: the Norwegian island of Spitzbergen, 500 miles from the North Pole. The civilian population of 700 has been evacuated and valuable coal mines wrecked.

It was a piquant operation. No Germans were present as an invasion force of Norwegians, Canadians and British landed to take over the radio station. When it was clear that the soldiers were welcome the force commander, from Saskatchewan, made a formal landing from a small commando craft and soon afterwards, at a community centre, was greeted by the commissar (Norway allows the USSR to mine on the island) and handed gifts of Russian cigarettes.

At the Norwegian settlement of Svalbard nearby, a Norwegian major read a proclamation from the exiled King Haakon. For several days the invaders billeted cheerfully with the locals. Before the final evacuation of Norwegians and Russian miners, parties took place and a dance at which Norwegian girls danced with the soldiers.

POLAND: The first experimental mass killings with gas in Auschwitz. (Mikko Härmeinen)

Since the autumn of 1939 the Germans have used carbon monoxide to kill their incurable mental patients and other “undesirables.” Today Rudolf Hoess, the commandant here, tried out a new method.

He chose 600 Russian prisoners of war and 250 Jews from the infirmary to be his guinea pigs. Crammed into a cellar, they noticed that the windows had been blocked up. Suddenly the door opened and guards threw in a powder. Cyanide fumes filled the room and soon they were dead. The experiment was later judged a success.

The powder, Zyklon B, is crystalline prussic acid, supplied by a Hamburg firm under licence from the chemical giant IG Farben. It is usually used for killing rats.

U.S.S.R.: Moscow: All Russian men aged 18 or over are called up for military service.

CHINA: Chinese forces recapture Foochow from Japan.

U.S.A.: Heavy cruiser USS Canberra (ex Pittsburgh) is laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: U-567 sinks the Fort Richepanse. U-109 sinks SS Ocean Might in Convoy OS-37. U-107 sinks SS Hollinside and SS Penrose. (Dave Shirlaw)

The Japanese consider most of the Pacific to be Japanese waters.

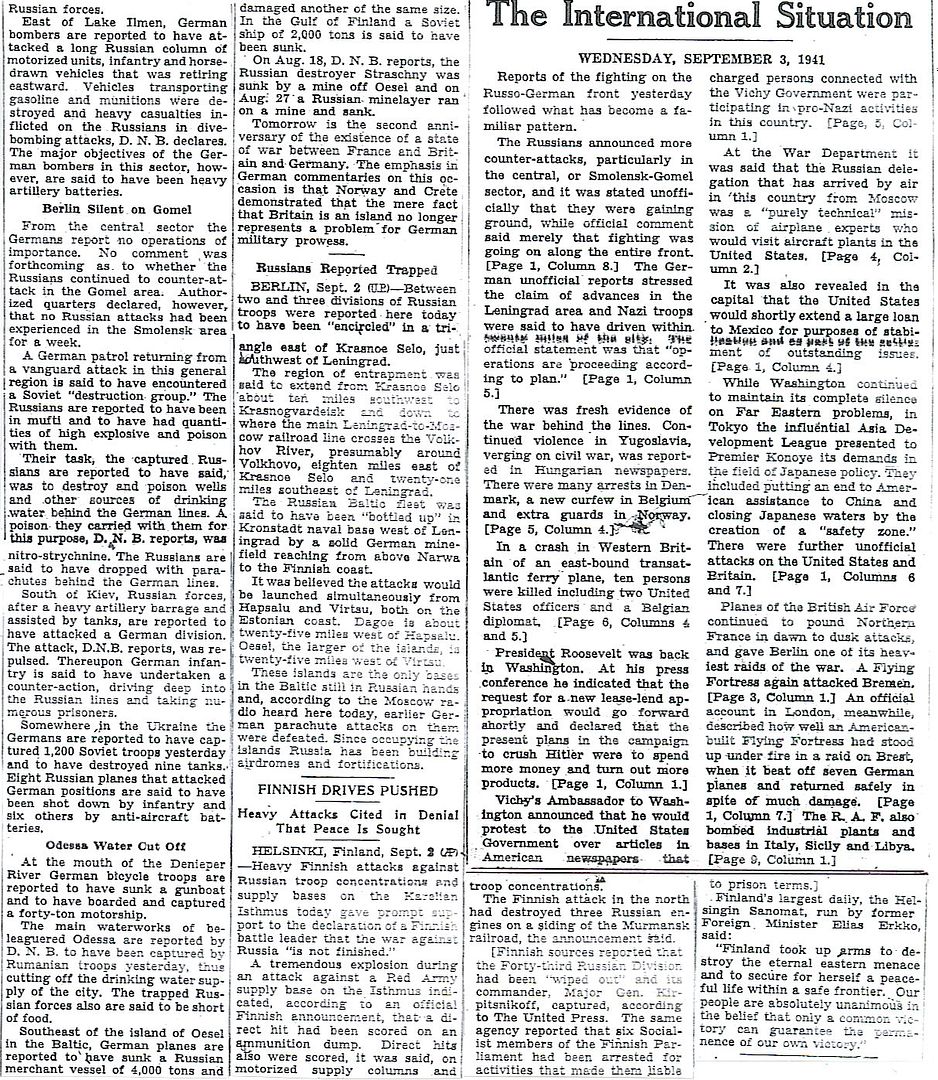

Interesting that in a 2 year overview of the War it is deemed a stalemate at this point. Of course there is winter coming on the Russian front which will be a killer for the Nazi military. Of course before the year ends America will join the battle to kill people and break things.

“On September 3, 1941, around 600 Soviet prisoners of war and 250 sick Polish prisoners were gassed with Zyklon B at Auschwitz camp I; this was the first experiment with the gas at Auschwitz. The experiments lasted more than 20 hours.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zyklon_B

"Under the control of Einsatzgruppe B of the SS, these dejected Jewish men in Mogilev, Belorussia, march to forced labor or death.

The large size of the Star of David on their clothing suggests that this photograph may have been intended as part of a propaganda film, designed to fuel hatred of the Jew as a subhuman threat to society.

Oversized stars, signs hung around necks, degrading labor--all of these were filmed and photographed to transform human beings into the sorts of Jewish caricatures favored by Nazi cartoonists and illustrators."

In Septembere there begin to be almost daily events relating to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

I'll post as many as I can, but may miss some -- indeed have already missed some important points.

Just finished a very good book: Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941-1944, by Anna Reid.

It began 9/08/41. Seventy years ago. Over half a million died.

Bookworm ping.

Half a million? I thought it was even more than that.

I'm pretty sure the death toll was well into the millions.

“Over half a million.”

Over = more than! :)

Einsatzgruppe ‘B’ was commanded by SS Gen. Artur Nebe, Chief of the German Criminal Police. He was the only Einsatzgruppe commander to volunteer for the job, and did so without knowing what the job was. Nebe was involved in the 20th of July plot, and was executed by the SS.

A subunit of the Gruppe won notoriety for conducting a “model” execution unde the eyes of Reichsfuehrer SS Heinrich Himmler, which caused him to become physically ill. This led, in part, to Himmler’s search for a quicker, cheaper, less traumatizing [to the executioners] method of murderthat increasingly turned to poison gas.

LENINGRAD (excerpt)

The centre of the fighting is gravitating more and more northwards so, in September 1941, we are sent to Tyrkowo, south of Luga, in the northern sector of the Eastern front.

We go out daily over the Leningrad area where the army has opened an offensive from the west and from the south. Lying as it does between the Finnish Gulf and Lake Ladoga, the geographical position of Leningrad is a big advantage to the defenders since the possible ways of attacking it are strictly limited. For some time progress here has been slow. One almost has the impression that we are merely marking time.

On the 16th September Flight Lieutenant Steen summons us to a conference. He explains the military situation and tells us that the particular difficulty holding up the further advance of our armies is the presence of the Russian fleet moving up and down the coast at a certain distance from the shore and intervening in the battles with their formidable naval guns. The Russian fleet is based on Kronstadt, an island in the Gulf of Finland, the largest war harbor in the U.S.S.R. Approximately 12-1/2 miles from Kronstadt lies the harbor of Leningrad and south of it the ports of Oranienbaum and Peterhof.

Very strong enemy forces are massed round these two towns on a strip of coast some six miles long. We are told to mark all the positions precisely on our maps so as to ensure our being able to recognize our own front line. We are beginning to guess that these troop concentrations will be our objective when Flt./Lt. Steen gives another turn to the briefing. He comes back to the Russian fleet and explains that our chief concern is the two battleships Marat and Oktobrescaja Revolutia. Both are ships of about 23,000 tons. In addition, there are four or five cruisers, among them the Maxim Gorki and the Kirov, as well as a number of destroyers. The ships constantly change their positions according to which parts of the mainland require the support of their devastating and accurate gunfire. As a rule, however, the battleships navigate only in the deep channel between Kronstadt and Leningrad.

Our wing has just received orders to attack the Russian fleet in the Gulf of Finland.

There is no question of using normal bomber-aircraft, any more than normal bombs, for this operation, especially as intense flak must be reckoned with. He tells us that we are awaiting the arrival of two thousand pounder bombs fitted with a special detonator for our purpose. With normal detonators the bomb would burst ineffectively on the armored main deck and though the explosion would be sure to rip off some parts of the upper structure it would not result in the sinking of the ship. We cannot expect to succeed and finish off these two leviathans except by the use of a delayed action bomb which must first pierce the upper decks before exploding deep down in the hull of the vessel.

A few days later, in the foulest weather, we are suddenly ordered to attack the battleship Marat; she has just been located in action by a reconnaissance patrol. The weather is reported as bad until due South of Krasnowardeisk, 20 miles South of Leningrad. Cloud density over the Gulf of Finland 5-7/10; cloud base 2400 feet. That will mean flying through a layer of cloud which where we are is 6000 feet thick. The whole wing takes off on a Northerly course. Today we are about thirty aircraft strong; according to our establishment we should have eighty, but numbers are not invariably the decisive factor. Unfortunately the two thousand pounders have not yet arrived. As our single engine Stukas are not capable of flying blind our No. 1 has to do the next best thing and keep direction with the help of the few instruments: ball, bank indicator and vertical speed indicator. The rest of us keep station by flying close enough to one another to be able to catch an occasional glimpse of our neighbor’s wing. Flying in the dense, dark clouds it is imperative never to let the interval between the tips of our wings exceed 9-12 feet. If it is greater we risk losing our neighbor for good and running full tilt into an other aircraft. This is an awe-inspiring thought! In such weather conditions therefore the safety of the whole wing is in the highest degree dependent on the instrument flying of our No. 1.

Below 6000 feet we are in a dense cloud cover; the individual flights have slightly broken formation.

Now they close up again. There is still no ground visibility. Reckoning by the clock we must pretty soon be over the Gulf of Finland. Now, too, the cloud cover is thinning out a little. There is a glint of blue sky below us; ergo water. We should be approaching our target, but where exactly are we? It is impossible to tell because the rifts in the clouds are only infinitesimal. The cloud density can no longer be anything like 5-7/10; only here and there the thick soup dissolves to reveal an isolated gap. Suddenly through one such gap I see something and instantly contact Fit. Lt. Steen over, the radio.

"Konig 2 to Konig 1 ... come in, please."

He immediately answers:

"Konig 1 to Konig 2 ... over to you."

"Are you there? I can see a large ship below us ... the battleship Marat, I guess."

We are still talking as Steen loses height and disappears into the gap in the clouds. In mid-sentence I also go into a dive. Pilot Officer Klaus behind me in the other staff aeroplane follows suit. Now I can make out the ship. It is the Marat sure enough. I suppress my excitement with an iron will. To make up my mind, to grasp the situation in a flash: for this I have only seconds. It is we who must hit the ship, for it is scarcely likely that all the flights will get through the gap. Both gap and ship are moving. We shall not be a good target for the flak until in our dive we reach the cloud base at 2400 feet. As long as we are above the unbroken cloud base the flak can only fire by listening apparatus, they cannot open up properly. Very well then: dive, drop bombs and back into the clouds! The bombs from Steen's aircraft are already on their way down . . . near misses. I press the bomb switch . . .dead on. My bomb hits the after deck. A pity it is only a thousand pounder! All the same I see flames break out. I cannot afford to hang about to watch it, for the flak barks furiously. There, the others are still diving through the gap. The Soviet flak has by this time realized where the "filthy Stukas" are coming from and concentrate their fire on this point. We exploit the favorable cloud cover and climb back into it.

Nevertheless, at a later date, we are not to escape from this area so relatively unscathed.

Once we are home again the guessing game immediately begins: what can have been the extent of the damage to the ship after the direct hit?

Naval experts claim that with a bomb of this small caliber a total success must be discounted. A few optimists, on the other hand, think it possible. As if to confirm their opinion, in the course of the next few days our reconnaissance patrols, despite the most enterprising search, are quite unable to find the Marat.

Stuka dive-bombers attack the battleship Marat in Kronstadt harbour

In an ensuing operation a cruiser sinks in a matter of minutes under my bomb.

After the first sortie our luck with the weather is out. Always a brilliant blue sky and murderous flak. I never again experience anything to compare with it in any place or theatre of war. Our reconnaissance estimates that a hundred A.A. guns are concentrated in an area of six-square miles in the target zone. The flak bursts form a whole cumulus of cloud. If the explosions are more than ten or twelve feet away one cannot hear the flak from the flying aircraft. But we hear no single bursts; rather an incessant tempest of noise like the clap of doomsday. The concentrated zones of flak in the air space begin as soon as we cross the coastal strip which is still in Soviet hands. Then come Oranienbaum and Peterhof; being harbors, very strongly defended.

The open water is alive with pontoons, barges, boats and tiny craft, all stiff with flak. The Russians use every possible site for their A.A. guns. For instance, the mouth of Leningrad harbor is supposed to have been closed to our U-boats by means of huge steel nets suspended from a chain of concrete blocks floating on the surface of the water. Even from these blocks A.A. guns bark at us.

After about another six miles we sight the island of Kronstadt with its great naval harbor and the town of the same name. Both harbor and town are heavily defended, and besides the whole Russian Baltic fleet is anchored in the immediate vicinity, in and outside the harbor. And it can put up a murderous barrage of flak. We in the leading staff aircraft always fly at an altitude between 9,000 and 10,000 feet; that is very low, but after all we want to hit something. When diving onto the ships we use our diving brakes in order to check our diving speed. This gives us more time to sight our target and to correct our aim. The more carefully we aim, the better the results of our attack, and everything depends on them. By reducing our diving speed we make it easier for the flak to bring us down, especially as if we do not overshoot we cannot climb so fast after the dive. But, unlike the flights behind us, we do not generally try to climb back out of the dive. We use different tactics and pull out at low level close above the water. We have then to take the widest evasive action over the enemy-occupied coastal strip. Once we have left it behind we can breathe freely again. We return to our airfield at Tyrkowo from these sorties in a state of trance and fill our lungs with the air we have won the right to continue to breathe.

On the 21st September our two thousand pounders arrive.

The next morning reconnaissance reports that the Marat is lying in Kronstadt harbor. They are evidently repairing the damage sustained in our attack of the 16th. I just see red. Now the day has come for me to prove my ability. I get the necessary information about the wind, etc., from the reconnaissance men.

Then I am deaf to all around me; I am longing to be off. If I reach the target, I am determined to hit it. I must hit it!—We take off with our minds full of the attack; beneath us, the two thousand pounders which are to do the job today. Brilliant blue sky, without a rack of cloud. The same even over the sea. We are already attacked by Russian fighters above the narrow coastal strip; but they cannot deflect us from our objective, there is no question of that. We are flying at 9000 feet; the flak is deadly.

About ten miles ahead we see Kronstadt; it seems an infinite distance away. With this intensity of flak one stands a good chance of being hit at any moment. The waiting makes the time long. Dourly, Steen and I keep on our course. We tell ourselves that Ivan is not firing at single aircraft; he is merely putting up a flak barrage at a certain altitude. The others are all over the sky, not only in the squadrons and flights, but even in the pairs. They think that by varying height and zigzagging they can make the A.A. gunners' task more difficult.

There go the two blue-nosed staff aircraft sweeping through all the formations, even the separate flights. Now one of them loses her bomb. A wild helter-skelter in the sky over Kronstadt; the danger of ramming is great. We are still a few miles from our objective; at an angle ahead of me I can already make out the Marat berthed in the harbor. The guns boom, the shells scream up at us, bursting in flashes of livid colors; the flak forms small fleecy clouds that frolic around us. If it was not in such deadly earnest one might use the phrase: an aerial carnival. I look down on the Marat. Behind her lies the cruiser Kirov. Or is it the Maxim Gorki?

These ships have not yet joined in the general bombardment. But it was the same the last time. They do not open up on us until we are diving to the attack. Never has our flight through the defense seemed so slow or so uncomfortable. Will Steen use his diving brakes today or in the face of this opposition will he go in for once "without"?

There he goes. He has already used his brakes.

I follow suit, throwing a final glance into his cockpit. His grim face wears an expression of concentration. Now we are in a dive, close beside each other. Our diving angle must be between seventy and eighty degrees. I have already picked up the Marat in my sights. We race down towards her; slowly she grows to a gigantic size. All their A.A. guns are now directed at us. Now nothing matters but our target, our objective; if we achieve our task it will save our brothers in arms on the ground much bloodshed.

But what is happening? Steen's aircraft suddenly leaves mine far behind. He is traveling much faster. Has he after all again retracted his diving brakes in order to get down more quickly? So I do the same. I race after his aircraft going all out. I am right on his tail, traveling much too fast and unable to check my speed. Straight ahead of me I see the horrified face of W.O. Lehmann, Steen's rear-gunner. He expects every second that I shall cut off his tail unit with my propeller and ram him.

I increase my diving angle with all the strength I have got—-it must surely be 90 degrees—sit tight as if I were sitting on a powderkeg. Shall I graze Steen's aircraft which is right on me or shall I get safely past and down? I streak past him within a hair's breadth. Is this an omen of success? The ship is centered plumb in the middle of my sights. My Ju 87 keeps perfectly steady as I dive; she does not swerve an inch. I have the feeling that to miss is now impossible. Then I see the Marat large as life in front of me. Sailors are running across the deck, carrying ammunition. Now I press the bomb release switch on my stick and pull with all my strength. Can I still manage to pull out? I doubt it, for I am diving without brakes and the height at which I have released my bomb is not more than 900 feet. The skipper has said when briefing us that the two thousand pounder must not be dropped from lower than 3000 feet as the fragmentation effect of this bomb reaches 3000 feet and to drop it at a lower altitude is to endanger one's aircraft. But now I have forgotten that!—I am intent on hitting the Marat. I tug at my stick, without feeling, merely exerting all my strength. My acceleration is too great. I see nothing, my sight is blurred in a momentary blackout, a new experience for me. But if it can be managed at all I must pull out. My head has not yet cleared when I hear Schamovski's voice: " She is blowing up, sir!"

Now I look out. We are skimming the water at a level of ten or twelve feet and I bank round a little.

Yonder lies the Marat below a cloud of smoke rising up to 1200 feet; apparently the magazine has exploded.

"Congratulations, sir."

Schamovski is the first. Now there is a babel of congratulations from all the other aircraft over the radio. From all sides I catch the words: "Good show!" Hold on, surely I recognize the Wing Commander's voice? I am conscious of a pleasant glow of exhilaration such as one feels after a successful athletic feat. Then I fancy that I am looking into the eyes of thousands of grateful infantrymen. Back at low level in the direction of the coast.

"Two Russian fighters, sir," reports Schamovski.

"Where are they?"

"Chasing us, sir.-—They are circling round the fleet in their own flak.—Cripes! They will both be shot down together by their own flak."

This expletive and, above all, the excitement in Schamovski's voice are something quite new to me. This has never happened before. We fly on a level with the concrete blocks on which A.A. guns have also been posted. We could almost knock the Russian crews off them with our wings. They are still firing at our comrades who are now attacking the other ships. Then for a moment there is nothing visible through the pall of smoke rising from the Marat. The din down below on the surface of the water must be terrific, for it is not until now that a few flak crews spot my aircraft as it roars close past them. Then they swivel their guns and fire after me; all have had their attention diverted by the main formation flying off high above them. So the luck is with me, an isolated aircraft. The whole neighbourhood is full of A.A. guns; the air is peppered with shrapnel. But it is a comfort to know that this weight of iron is not meant exclusively for me! I am now crossing the coast line. The narrow strip is very unpleasant. It would be impossible to gain height because I could not climb fast enough to reach a safe altitude. So I stay down. Past machine guns and flak. Panic-stricken Russians hurl themselves flat on the ground.

Then again Schamovski shouts:

"A Rata coming up behind us!"

I look round and see a Russian fighter about 300 yards astern.

"Let him have it, Schamovski!"

Schamovski does not utter a sound. Ivan is blazing away at a range of only a few inches. I take wild evasive action.

"Are you mad, Schamovski? Fire! I'll have you put under arrest." I yell at him!

Schamovski does not fire. Now he says deliberately: "I am holding fire, sir, because I can see a German Me coming up behind and if I open up on the Rata I may damage the Messerschmitt." That closes the subject as far as Schamovski is concerned; but I am sweating with the suspense. The tracers are going wider on either side of me. I weave like mad.

"You can turn round now, sir. The Me has shot down the Rata." I bank round slightly and look back. It is as Schamovski says; there she lies down below. Now a Me passes groggily. " Schamovski, it will be a pleasure to confirm our fighter's claim to have shot that one down." He does not reply. He is rather hurt that I was not content to trust his judgment before. I know him; he will sit there and sulk until we land. How many operational flights have we made together when he has not opened his lips the whole time we have been in the air.

After landing, all the crews are paraded m front of the squadron tent. We are told by Flt./Lt. Steen that the Wing Commander has already rung up to congratulate the 3rd squadron on its achievement. He had personally witnessed the very impressive explosion. Steen is instructed to report the name of the officer who was the first to dive and drop the successful two thousand pounder in order that he may be recommended for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. With a side-glance in my direction he says: "Forgive me for telling the Kommodore that I am so proud of the whole squadron that I would prefer it if our success is attributed to the squadron as a whole." In the tent he wrings my hand. "You no longer need a battleship for special mention in despatches," he says with a boyish laugh.

The Wing Commander rings up. "It is sinking day for the 3rd. You are to take oft immediately for another attack on the Kirov berthed behind the Marat. Good hunting!" The photographs taken by our latest aircraft show that the Marat has split in two. This can be seen on the picture taken after the tremendous cloud of smoke from the explosion had begun to dissipate.

The telephone rings again: "I say, Steen, did you see my bomb? I didn't and neither did Pekrun."

"It fell into the sea, sir, a few minutes before the attack."

We youngsters in the tent are hard put to it to keep a straight face. A short crackling on the receiver and that is all. We are not the ones to blame our Wing Commander, who is old enough to be our father, if presumably out of nervousness he pressed the bomb release switch prematurely. He deserves all praise for flying with us himself on such a difficult mission. There is a big difference between the ages of fifty and twenty five. In dive bomber flying this is particularly true. Out we go again on a further sortie to attack the Kirov. Steen had a slight accident taxiing back after landing from the first sortie: one wheel ran into a large crater, his aircraft pancaked and damaged the propeller. The 7th flight provides us with a substitute aircraft, the flights are already on dispersal and we taxi off from our squadron base airfield. Ft./Lt. Steen again hits an obstacle and this aircraft is also unserviceable. There is no replacement available from the flights; they are of course already on dispersal. No one else on the staff is flying except myself. He therefore gets out of his aircraft and climbs onto my wingplane.

"I know you are going to be mad at me for taking your aircraft, but as I am in command I must fly with the squadron. I will take Schamovski with me for this one sortie."

Vexed and disgruntled I walk over to where our aircraft are overhauled and devote myself for a time to my job as engineer officer. The squadron returns at the end of an hour and a half. No. 1, the green-nosed staff aircraft—mine—is missing.

I assume the skipper has made a forced landing somewhere within our lines.

As soon as my colleagues have all come in I ask what has happened to the skipper. No one will give me a straight answer until one of them says: "Steen dived onto the Kirov. He was caught by a direct hit at 5000 or 6000 feet. The flak smashed his rudder and his aircraft was out of control. I saw him try to steer straight at the cruiser by using the ailerons, but he missed her and nose-dived into the sea. The explosion of his two thousand pounder seriously damaged the Kirov."

The loss of our skipper and my faithful Cpl. Scharnovski is a heavy blow to the whole squadron and makes a tragic climax to our otherwise successful day.

We are out again a number of times over the Gulf of Finland before the end of September, and we succeed in sending another cruiser to the bottom. We are not so lucky with the second battleship, Oktobrescaja Revolutia. She is damaged by bombs of smaller calibre but not very seriously. When we manage on one sortie to score a hit with a two thousand pounder, on that particular day not one of these heavy bombs explodes.

Despite the most searching investigation it is not possible to determine where the sabotage was done. So the Soviets keep one of their battleships. There is a lull in the Leningrad sector and we are needed at a new key point. The relief of the infantry has been successfully accomplished, the Russian salient along the coastal strip has been pushed back with the result that Leningrad has now been narrowly invested. But Leningrad does not fall, for the defenders hold Lake Ladoga and thereby secure the supply line for the fortress.

"The mortuary itself is full. Not only are there too few trucks to go to the cemetery, but, more important, not enough gasoline to put in the trucks and the main thing is - there is not enough strength left in the living to bury the dead." - Very Inber, Leningrad diary, 26 December 1941

As far as the exact numbers of dead in Leningrad, no one is really certain but the number is certainly high. In my monthly notes for this month I mentioned that the Soviet troops on the Leningrad Front will total up over 116,000 casualties between 23 August and 30 September alone. Now please note that casualties, does not mean deaths, but statistically the casualty to death rate in World War II is around 50 percent (Japan casualties are an outlier in this case for obvious reasons). That puts the Soviet deaths at around 55,000 just as the siege started.

By January, the system of registration of deaths broke down under the sheer strain of numbers. By this point, four to five thousand people were dying each day in the city. The Library of Congress estimates that in the 900 days of the siege of Leningrad, over 600,000 people had died from starvation alone. Combat death added in, we could easily be approaching a million.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.