Posted on 08/18/2010 2:28:10 AM PDT by Daffynition

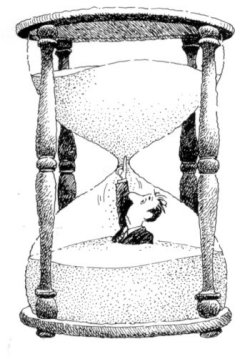

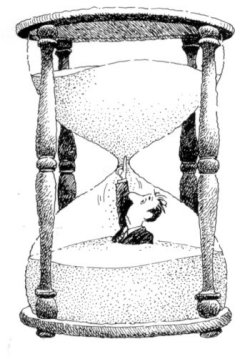

When David Eagleman was 8 years old, he went exploring. He found a house under construction — prime territory for an adventurous kid — and he climbed on the roof to check out the view. But what looked like the edge of the roof was just tar paper, and — you can feel it coming — when David stepped on it, he fell.

Whoosh … Thud.

David was fine. But between whoosh and the thud, something odd happened. As David remembers it, he noticed every detail of his surroundings: the edge of the roof moving past him, the red bricks below moving toward him. He even did a little literary analysis: "I was thinking about Alice in Wonderland, how this must be what it was like for her, when she fell down the rabbit hole."

All of that happened in just 0.86 seconds. David knows that now because he has calculated how long it takes to fall 12 feet. David Eagleman is now Dr. Eagleman, a neuroscientist at Baylor College of Medicine, and one of his specialties is exploring how our brains perceive and understand time.

Several years ago, motivated in part by his childhood plunge, David started studying the way our sense of time distorts in crisis situations. He has gathered a huge number of stories from people who have survived falls, car crashes, bike accidents, etc. Everyone, he says, seems to say the same thing: "It felt like the world was moving in slow motion."

But what is really going on? David started to think that maybe, in a crisis, the brain goes into a sort of turbo mode, processing everything at higher-than-normal-speed. If the brain were to speed up, he thought, the world would appear to slow down. This would work just like a slow-motion movie; in a slow-mo shot of a hummingbird, for example, you can see each individual wing movement in what would otherwise be just a blur.

Taking The Plunge

So David decided to craft an experiment to study this "slow-motion effect" in action. But to do that, he had to make people fear for their lives — without actually putting them in danger. His first attempt involved a field trip to Six Flags AstroWorld, an amusement park in Houston, Texas. He used his students as his subjects. "We went on all of the scariest roller coasters, and we brought all of our equipment and our stopwatches, and had a great time," David says. "But it turns out nothing there was scary enough to induce this fear for your life that appears to be required for the slow-motion effect."

But, after a little searching, David discovered something called SCAD diving. (SCAD stands for Suspended Catch Air Device.) It's like bungee jumping without the bungee. Imagine being dangled by a cable about 150 feet off the ground, facing up to the sky. Then, with a little metallic click, the cable is released and you plummet backward through the air, landing in a net (hopefully) about 3 seconds later.

SCAD diving was just what David needed — it was definitely terrifying. But he also needed a way to judge whether his subjects' brains really did go into turbo mode. So, he outfitted everybody with a small electronic device, called a perceptual chronometer, which is basically a clunky wristwatch. It flashes numbers just a little too fast to see. Under normal conditions — standing around on the ground, say — the numbers are just a blur. But David figured, if his subjects' brains were in turbo mode, they would be able to read the numbers.

The Time Blur

The falling experience was, just as David had hoped, enough to freak out all of his subjects. "We asked everyone how scary it was, on a scale from 1 to 10," he reports, "and everyone said 10." And all of the subjects reported a slow-motion effect while falling: they consistently over-estimated the time it took to fall. The numbers on the perceptual chronometer? They remained an unreadable blur.

"Turns out, when you're falling you don't actually see in slow motion. It's not equivalent to the way a slow-motion camera would work," David says. "It's something more interesting than that."

According to David, it's all about memory, not turbo perception. "Normally, our memories are like sieves," he says. "We're not writing down most of what's passing through our system." Think about walking down a crowded street: You see a lot of faces, street signs, all kinds of stimuli. Most of this, though, never becomes a part of your memory. But if a car suddenly swerves and heads straight for you, your memory shifts gears. Now it's writing down everything — every cloud, every piece of dirt, every little fleeting thought, anything that might be useful.

Because of this, David believes, you accumulate a tremendous amount of memory in an unusually short amount of time. The slow-motion effect may be your brain's way of making sense of all this extra information. "When you read that back out," David says, "the experience feels like it must have taken a very long time." But really, in a crisis situation, you're getting a peek into all the pictures and smells and thoughts that usually just pass through your brain and float away, forgotten forever.

**I'm so fast that last night I turned off the light switch in my hotel room and was in bed before the room was dark.**

Good story. I won’t bore you with my slo-mo story, but I can recall it, with every motion in great detail, as it happened, in my mind’s eye...even though it was a decade ago. Amazing phenomenon.

..???

..???

When I went back to review the scene I realized that I had let him get a LOT closer, but it looked like 7 yards at the time.

Excellent! THAT’S THE ONE!

The F Bomb.

Now you've gone 'n dunit!!!

In The Matrix, hero Neo wins his battles when time slows in the simulated world. In the real world, accident victims often report a similar slowing as they slide unavoidably into disaster. But can humans really experience events in slow motion?

Apparently not, said researchers at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who studied how volunteers experience time when they free-fall 100 feet into a net below. Even though participants remembered their own falls as having taken one-third longer than those of the other study participants, they were not able to see more events in time. Instead, the longer duration was a trick of their memory, not an actual slow-motion experience. The study appears online today in the journal Public Library of Science One.

“People commonly report that time seemed to move in slow motion during a car accident,” said Dr. David Eagleman, assistant professor of neuroscience and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at BCM. “Does the experience of slow motion really happen, or does it only seem to have happened in retrospect? The answer is critical for understanding how time is represented in the brain.”

When roller coasters and other scary amusement park rides did not cause enough fear to make “time slow down,” Eagleman and his graduate students Chess Stetson and Matthew Fiesta sought out something even more frightening. They hit upon Suspended Catch Air Device diving, a controlled free-fall system in which “divers” are dropped backwards off a platform 150 feet up and land safely in a net. Divers are not attached to ropes and reach 70 miles per hour during the three-second fall.

“It’s the scariest thing I have ever done,” said Eagleman. “I knew it was perfectly safe, and I also knew that it would be the perfect way to make people feel as though an event took much longer than it actually did.”

The experiment consisted of two parts. In one, the researchers asked participants to reproduce with a stopwatch how long it took someone else to fall, and then how long their own fall seemed to have lasted. In general, people estimated that their own fall appeared 36 percent longer than that of their compatriots.

However, to determine whether that distortion meant they could actually see more events happening in time – like a camera in slow motion – Eagleman and his students developed a special device called the perceptual chronometer that was strapped to the volunteers’ wrists. Numbers flickered on the screen of the watch-like unit. The scientists adjusted the speed at which the numbers flickered until it was too fast for the divers to see.

They theorized that if time perception really slowed, the flickering numbers would appear slow enough for the divers to easily read while in free-fall.

They found that while the subjects were able to read numbers presented at normal speeds during the free-fall, they could not read them at faster-than-normal speeds.

“We discovered that people are not like Neo in The Matrix, dodging bullets in slow-mo. The paradox is that it seemed to participants as though their fall took a long time. The answer to the paradox is that time estimation and memory are intertwined: the volunteers merely thought the fall took a longer time in retrospect,” he said.

During a frightening event, a brain area called the amygdala becomes more active, laying down a secondary set of memories that go along with those normally taken care of by other parts of the brain.

“In this way, frightening events are associated with richer and denser memories. And the more memory you have of an event, the longer you believe it took,” Eagleman explained.

The study allowed them to deduce that a person’s perception of time is not a single phenomenon that speeds or slows. “Your brain is not like a video camera,” said Eagleman.

Eagleman and his team have been able to verify this conclusion in the laboratory. In an experiment that appeared in a recent issue of PLoS One, Eagleman and graduate student Vani Pariyadath used ‘oddballs’ in a sequence to bring about a similar duration distortion. For example, when they flashed on the computer screen a shoe, a shoe, a shoe, a flower and a shoe, viewers believed the flower stayed on the screen longer, even though it remained there the same amount of time as the shoes.

Pariyadath and Eagleman showed that even though durations are distorted during the oddball, other aspects of time – such as flickering lights or accompanying sounds – do not change.

The conclusion from both studies was the same.

“It can seem as though an event has taken an unusually long time, but it doesn’t mean your immediate experience of time actually expands. It simply means that when you look back on it, you believe it to have taken longer,” Eagleman said.

“This is related to the phenomenon that time seems to speed up as you grow older. When you’re a child, you lay down rich memories for all your experiences; when your older, you’ve seen it all before and lay down fewer memories. Therefore, when a child looks back at the end of a summer, it seems to have lasted forever; adults think it zoomed by.”

Funding for this research came from the National Institutes of Health.

The first paper is available at http://www.plosone.org/home.action when the embargo is lifted. The second is at http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0001264

For more information on Eagleman’s lab and SCAD diving: http://neuro.bcm.edu/eagleman

For video or pictures of the study involving Suspended Catch Air Device diving please contact Graciela Gutierrez 713-798-4710.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.