Posted on 09/30/2008 5:11:57 AM PDT by Homer_J_Simpson

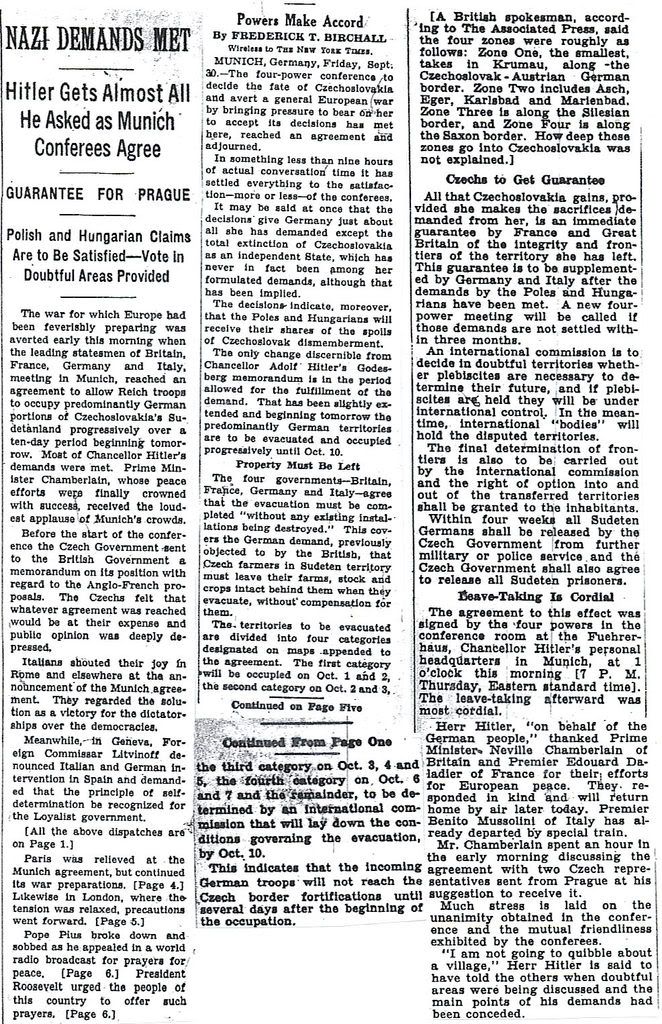

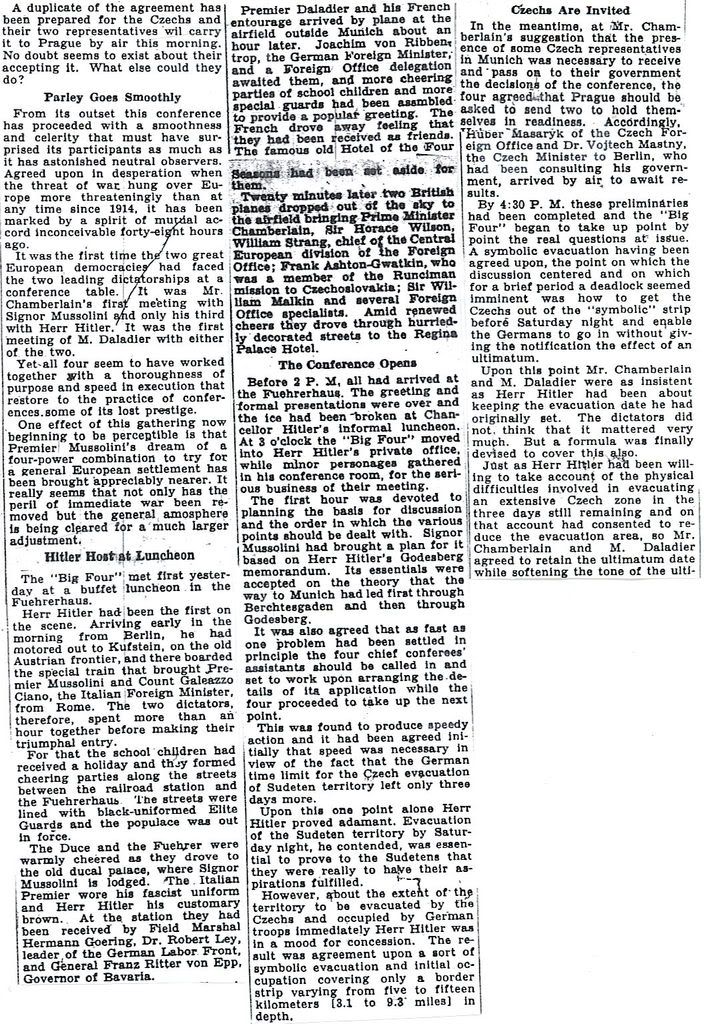

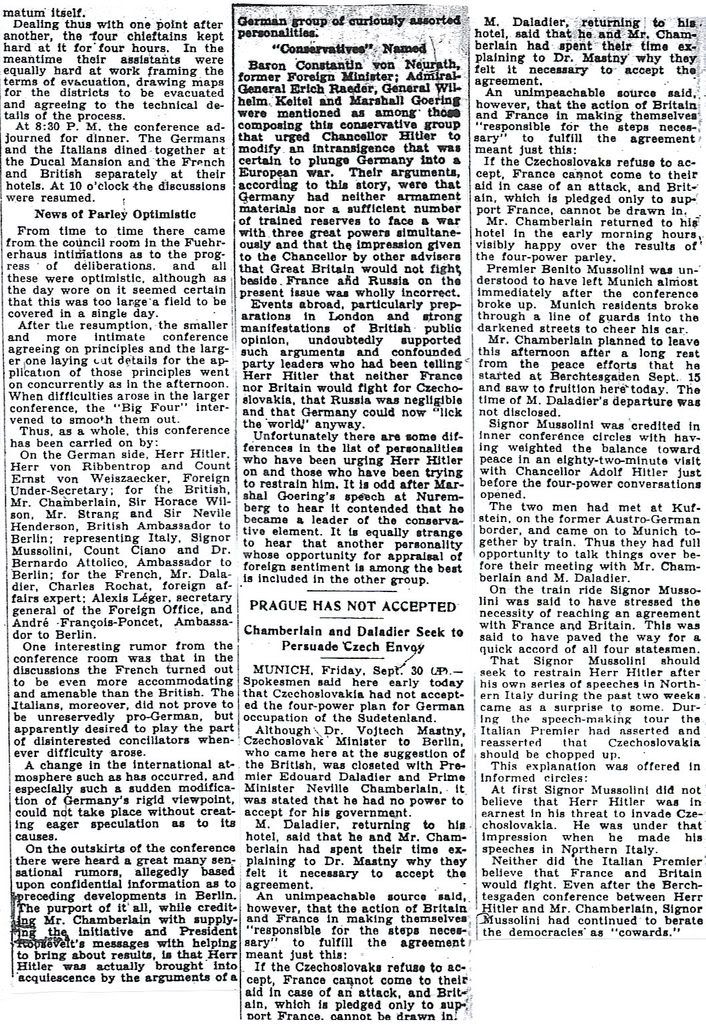

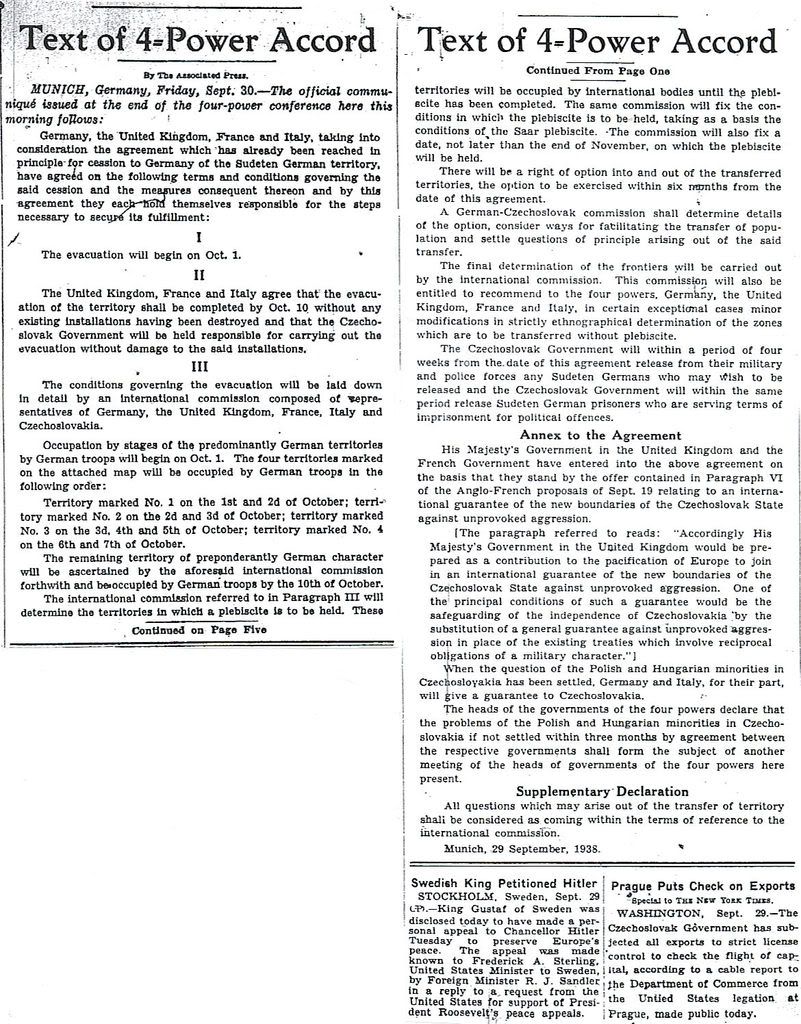

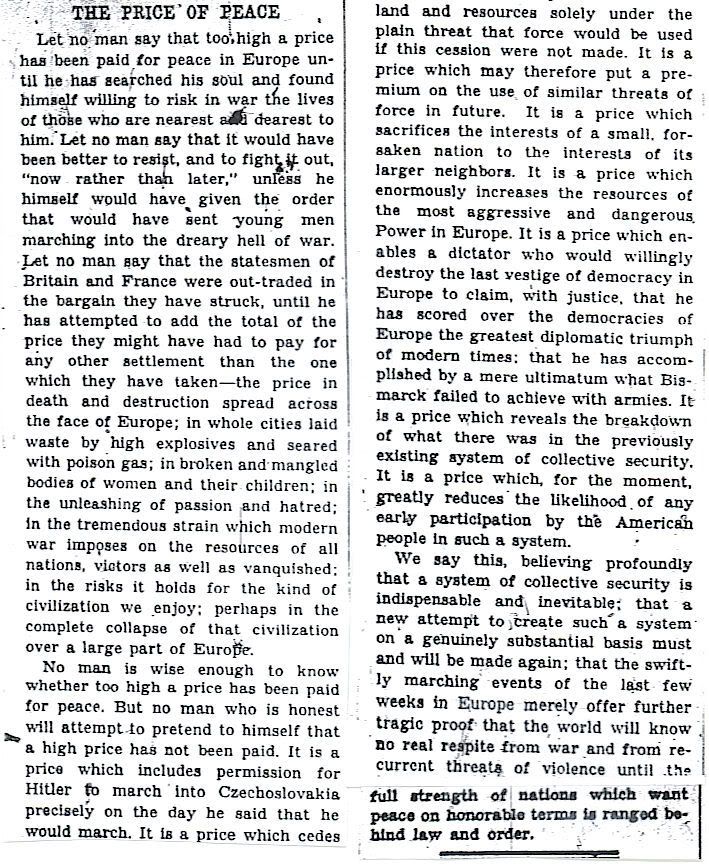

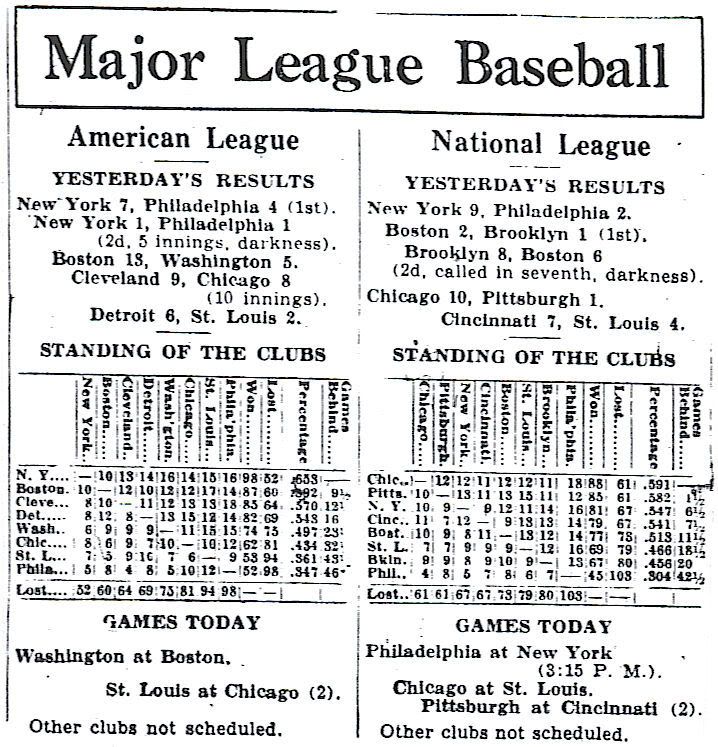

The conference has given birth to an accord, which is posted in full after the lead article. I repeated a couple paragraphs of the article on image 4 of 4 so you need to skip down a couple inches. The post closes with the lead editorial (”War is not the answer, but, jeez, can’t we do any better than this?”) and the Major League standings.

Chamberlain was not through conferring with Hitler about the peace of the world. Early the next morning, September 30, refreshed by a few hours of sleep and pleased with his labors of the previous day, he sought out the Fuehrer at his private apartment in Munich to discuss further the state of Europe and to secure a small concession which he apparently thought would improve his political position at home.

According to Dr. Schmidt, who acted as interpreter and who was the sole witness of this unexpected meeting, Hitler was pale and moody. He listened absent-mindedly as the exuberant head of the British government expressed his confidence that Germany would "adopt a generous attitude in the implementation of the Munich Agreement" and renewed his hope that the Czechs would not be "so unreasonable as to make difficulties" and that, if they did make them, Hitler would not bomb Prague "with the dreadful losses among the civilian population which it would entail." This was only the beginning of a long and rambling discourse which would seem incredible coming from a British Prime Minister, even one who had made so abject a surrender to the German dictator the night before, had it not been recorded by Dr. Schmidt in an official Foreign Office memorandum. Even today, when one reads this captured document, it seems difficult to believe.

But the British leader's opening remarks were only the prelude to what was to come. After what must have seemed to the morose German dictator an interminable exposition by Chamberlain in proposing further cooperation in bringing an end to the Spanish Civil War (which German and Italian "volunteers" were winning for Franco), in furthering disarmament, world economic prosperity, political peace in Europe and even a solution of the Russian problem, the Prime Minister drew out of his pocket a sheet of paper on which he had written something which he hoped they would both sign and release for immediate publication.

We, the German Fuehrer and Chancellor, and the British Prime Minister [it read], have had a further meeting today and are agreed in recognizing that the question of Anglo-German relations is of the first importance for the two countries and for Europe.

We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.

We are resolved that the method of consultation shall be the method adopted to deal with any other questions that may concern our two countries, and we are determined to continue our efforts to remove possible sources of difference, and thus to contribute to assure the peace of Europe.

Hitler read the declaration and quickly signed it, much to Chamberlain's satisfaction, as Dr. Schmidt noted in his official report. The interpreter's impression was that the Fuehrer agreed to it "with a certain reluctance . . . only to please Chamberlain," who, he recounts further, "thanked the Fuehrer warmly . . . and underlined the great psychological effect which he expected from this document."

The deluded British Prime Minister did not know, of course, that, as the secret German and Italian documents would reveal much later, Hitler and Mussolini had already agreed at this very meeting in Munich that in time they would have to fight "side by side" against Great Britain. Nor, as we shall shortly see, did he divine much else that already was fermenting in Hitler's lugubrious mind.

Chamberlain returned to London—as did Daladier to Paris—in triumph. Brandishing the declaration which he had signed with Hitler, the jubilant Prime Minister faced a large crowd that pressed into Downing Street. After listening to shouts of "Good old Neville!" and a lusty singing of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow," Chamberlain smilingly spoke a few words from a second-story window in Number 10.

"My good friends," he said, "this is the second time in our history that there has come back from Germany to Downing Street peace with honor. I believe it is peace in our time."

The Times declared that "no conqueror returning from a victory on the battlefield has come adorned with nobler laurels." There was a spontaneous movement to raise a "National Fund of Thanksgiving" in Chamberlain's honor, which he graciously turned down. Only Duff Cooper, the First Lord of the Admiralty, resigned from the cabinet, and when in the ensuing Commons debate Winston Churchill, still a voice in the wilderness, began to utter his memorable words, "We have sustained a total, unmitigated defeat," he was forced to pause, as he later recorded, until the storm of protest against such a remark had subsided. The mood in Prague was naturally quite different. At 6:20 A.M. on September 30, the German charge d'affaires had routed the Czech Foreign Minister, Dr. Krofta, out of bed and handed him the text of the Munich Agreement together with a request that Czechoslovakia send two representatives to the first meeting of the "International Commission," which was to supervise the execution of the accord, at 5 P.M. in Berlin.

For President Benes, who conferred all morning at the Hradschin Palace with the political and military leaders, there was no alternative but to submit. Britain and France had not only deserted his country but would now back Hitler in the use of armed force should he turn down the terms of Munich. At ten minutes to one, Czechoslovakia surrendered, "under protest to the world," as the official statement put it. "We were abandoned. We stand alone," General Sirovy, the new Premier, explained bitterly in a broadcast to the Czechoslovak people at 5 P.M.

To the very last Britain and France maintained their pressure on the country they had seduced and betrayed. During the day the British, French and Italian ministers went to see Dr. Krofta to make sure that there was no last-minute revolt of the Czechs against the surrender. The German charge, Dr. Hencke, in a dispatch to Berlin described the scene.

The French Minister's attempt to address words of condolence to Krofta was cut short by the Foreign Minister's remark: "We have been forced into this situation; now everything is at an end; today it is our turn, tomorrow it will be the turn of others.” The British Minister succeeded with difficulty in saying that Chamberlain had done his utmost; he received the same answer as the French Minister. The Foreign Minister was a completely broken man and intimated only one wish; that the three Ministers should quickly leave the room.

William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, pp. 420-421

There there is the speech he gave upon his return. This is the peace in our time speech though it cuts off before it actually gets to that statement.

Finally here is Max Jordon of NBC reporting from Munich.

Another interesting lesson in history, thanks for posting it.

Ping.

lugubrious:

1: mournful ; especially : exaggeratedly or affectedly mournful [dark, dramatic and lugubrious brooding — V. S. Pritchett]

2: dismal [lugubrious landscape]

So, Chamberlain, having abjectly surrendered to Hitler was "exuberant," while Hitler, having just scored the greatest victory ever for German diplomacy was "pale and moody," -- lugubrious!

"It is not easy in these latter days, when we have all passed through years of intense moral and physical stress and exertion, to portray for another generation the passions which raged in Britain about the Munich Agreement.

"Among the Conservatives families and friends in intimate contact were divided to a degree the like of which I have never seen, men and women, long bound together by party ties, social amenities, and family connections, glared upon one another in scorn and anger.

"The issue was not one to be settled by the cheering crowds which had welcomed Mr. Chamberlain back from the airport or blocked Downing Street and its approaches, nor by the redoubtable exertions of the Ministerial Whips and partisans. We who were in a minority at the moment cared nothing for the jokes or scowls of the Government supporters.

"The Cabinet was shaken to its foundations, but the event had happened and they held together. One Minister alone stood forth. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Mr. Duff Cooper, resigned his great office, which he had dignified by the mobilization of the Fleet. At the moment of Mr. Chamberlain's overwhelming mastery of public opinion he thrust his way through the exulting throng to declare his total disagreement with its leader.

"At the opening of the three days' debate on Munich he made his resignation speech. This was a vivid incident in our parliamentary life. Speaking with ease and without a note, for forty minutes he held the hostile majority of his party under his spell. It was easy for Labour men and Liberals in hot opposition to the Government of the day to applaud him. This was a rending quarrel within the Tory Party.

"The debate which took place was not unworthy of the emotions aroused and the issues at stake. I well remember that when I said, 'We have sustained a total and unmitigated defeat,' the storm which met me made it necessary to pause for a while before resuming.

"There was widespread and sincere admiration for Mr. Chamberlain's persevering and unflinching efforts to maintain peace, and for the personal exertions which he had made. It is impossible in this account to avoid marking the long series of miscalculations, and misjudgments of men and facts, on which he based himself; but the motives which inspired him have never been impugned, and the course he followed required the highest degree of moral courage. To this I paid tribute two years later in my speech after his death.

"There was also a serious and practical line of argument, albeit not to their credit, on which the Government could rest themselves. No one could deny that we were hideously unprepared for war. Who had been more forward in proving this than I and my friends? Great Britain had allowed herself to be far surpassed by the strength of the German Air Force. All our vulnerable points were unprotected. Barely a hundred anti-aircraft guns could be found for the defense of the largest city and centre of population in the world; and these were largely in the hands of untrained men.

"If Hitler was honest and lasting peace had in fact been achieved, Chamberlain was right. If, unhappily, he had been deceived, at least we should gain a breathing space to repair the worst of our neglects.

"These considerations, and the general relief and rejoicing that the horrors of war had been temporarily averted, commanded the loyal assent of the mass of government supporters. The House approved the policy of His Majesty's Government "by which war was averted in the recent crisis" by 266 to 144.

"The thirty or forty dissident Conservatives could do no more than register their disapproval by abstention. This we did as a formal and united act."

You left out the next part.

Some of the truths he uttered must be recorded here:

I besought my colleagues not to see this problem always in terms of Czechoslovakia, not to review it always from the difficult strategic position of that small country, but rather to say to themselves, "A moment may come when, owing to the invasion of Czechoslovakia, a European war will begin, and when that moment comes we must take part in that war, we cannot keep out of it, and there is no doubt upon which side we shall fight." Let the world know that, and it will give those who are prepared to disturb the peace reason to hold their hand. . . .

Then came the last appeal from the Prime Minister on Wednesday morning. For the first time from the beginning to the end of the four weeks of negotiations Herr Hitler was prepared to yield an inch, an ell perhaps, but to yield some measure to the representations of Great Britain. But I would remind the House that the message from the Prime Minister was not the first news that he had received that morning. At dawn he had learned of the mobilisation of the British Fleet. It is impossible to know what are the motives of man, and we shall probably never be satisfied as to which of these two sources of inspiration moved him most when he agreed to go to Munich; but we do know that never before had he given in, and that then he did. I had been urging the mobilisation of the Fleet for many days. I had thought that this was the kind of language which would be easier for Herr Hitler to understand than the guarded language of diplomacy or the conditional clauses of the Civil Service. I had urged that something in that direction might be done at the end of August and before the Prime Minister went to Berchtesgaden. I had suggested that it should accompany the mission of Sir Horace Wilson. I remember the Prime Minister stating it was the one thing that would ruin that mission, and I said it was the one thing that would lead it to success.

That is the deep difference between the Prime Minister and myself throughout these days. The Prime Minister has believed in addressing Herr Hitler through the language of sweet reasonableness. I have believed that he was more open to the language of the mailed fist. . . .

The Prime Minister has confidence in the goodwill and in the word of Herr Hitler, although when Herr Hitler broke the Treaty of Versailles he undertook to keep the Treaty of Locarno, and when he broke the Treaty of Locarno he undertook not to interfere further, or to have further territorial claims in Europe. When he entered Austria by force he authorised his henchmen to give an authoritative assurance that he would not interfere with Czechoslovakia. That was less than six months ago. Still the Prime Minister believes that he can rely upon the good faith of Hitler.

Here are a couple related excerpts from Shirer.

President Benes resigned on October 5 on the insistence of Berlin and, when it became evident that his life was in danger, flew to England and exile. He was replaced provisionally by General Sirovy.

. . . what must have amazed Hitler most of all – it certainly astounded General Beck, Hassell and others in their small circle of opposition—was that none of the men who dominated the governments of Britain and France ("little worms," as the Fuehrer contemptuously spoke of them in private after Munich) realized the consequences of their inability to react with any force to one after the other of the Nazi leader's aggressive moves.

Winston Churchill, in England, alone seemed to understand. No one stated the consequences of Munich more succinctly than he in his speech to the Commons of October 5:

We have sustained a total and unmitigated defeat . . . We are in the midst of a disaster of the first magnitude. The road down the Danube . . . the road to the Black Sea has been opened . . . All the countries of Mittel Europa and the Danube valley, one after another, will be drawn in the vast system of Nazi politics . . . radiating from Berlin . . . And do not suppose that this is the end. It is only the beginning ...

But Churchill was not in the government and his words went unheeded.

William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, pp. 421, 423

wow. the edtitorial is amazing, and prophetic.

continues to amaze me that either many of our now national leaders know nothing of history or they are just liars. hmmm.. maybe both?

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.