Posted on 05/30/2023 11:54:00 AM PDT by Red Badger

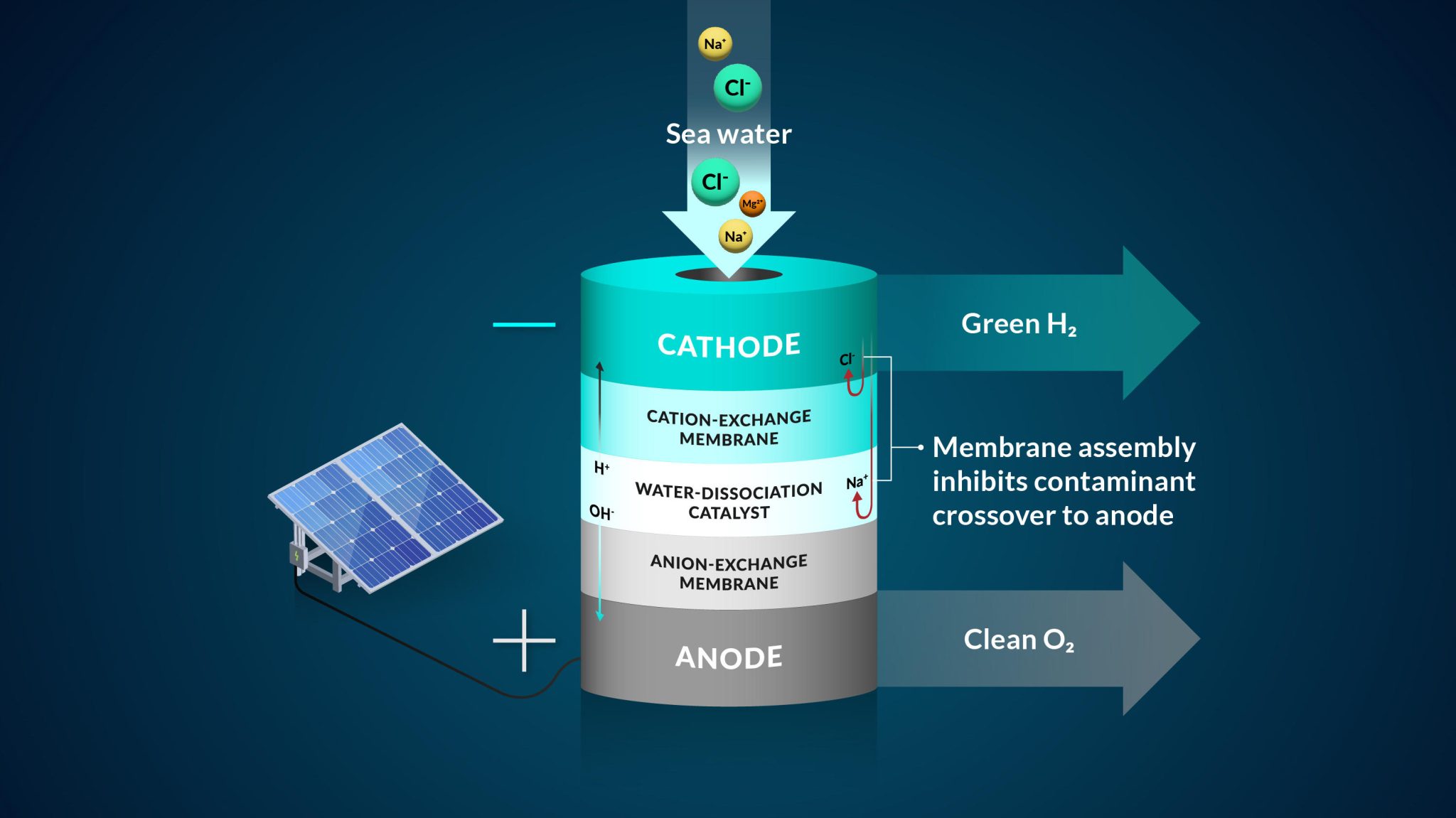

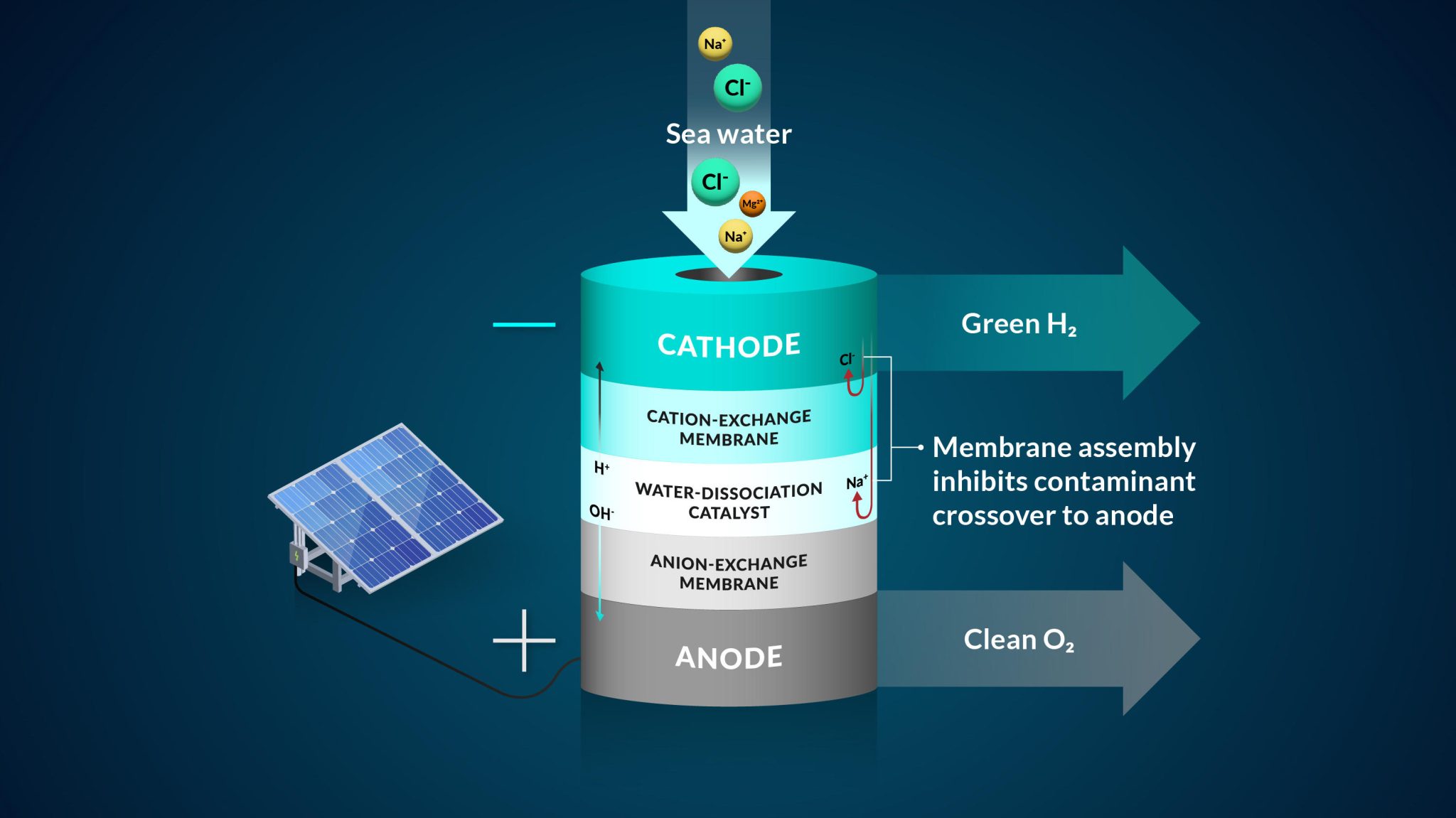

A representation of the team’s bipolar membrane system that converts seawater into hydrogen gas. Credit: Nina Fujikawa/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

The cocktail of elements in seawater, including hydrogen, oxygen, sodium, and others, is essential for life on Earth. However, this intricate chemical makeup poses a challenge when attempting to separate hydrogen gas for sustainable energy applications.

Recently, a team of scientists from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, University of Oregon, and Manchester Metropolitan University has discovered a method to extract hydrogen from the ocean. They accomplish this by funneling seawater through a double-membrane system and electricity.

Their innovative design proved successful in generating hydrogen gas without producing large amounts of harmful byproducts. The results of their study, recently published in the journal Joule, could help advance efforts to produce low-carbon fuels.

“Many water-to-hydrogen systems today try to use a monolayer or single-layer membrane. Our study brought two layers together,” said Adam Nielander, an associate staff scientist with the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, a SLAC-Stanford joint institute. “These membrane architectures allowed us to control the way ions in seawater moved in our experiment.”

Hydrogen gas is a low-carbon fuel currently used in many ways, such as to run fuel-cell electric vehicles and as a long-duration energy storage option – one that is suited to store energy for weeks, months, or longer – for electric grids.

Many attempts to make hydrogen gas start with fresh or desalinated water, but those methods can be expensive and energy intensive. Treated water is easier to work with because it has less stuff – chemical elements or molecules – floating around. However, purifying water is expensive, requires energy, and adds complexity to devices, the researchers said. Another option, natural freshwater, also contains a number of impurities that are problematic for modern technology, in addition to being a more limited resource on the planet, they said.

To work with seawater, the team implemented a bipolar, or two-layer, membrane system and tested it using electrolysis, a method that uses electricity to drive ions, or charged elements, to run a desired reaction. They started their design by controlling the most harmful element to the seawater system – chloride, said Joseph Perryman, a SLAC and Stanford postdoctoral researcher.

“There are many reactive species in seawater that can interfere with the water-to-hydrogen reaction, and the sodium chloride that makes seawater salty is one of the main culprits,” Perryman said. “In particular, chloride that gets to the anode and oxidizes will reduce the lifetime of an electrolysis system and can actually become unsafe due to the toxic nature of the oxidation products that include molecular chlorine and bleach.”

The bipolar membrane in the experiment allows access to the conditions needed to make hydrogen gas and mitigates chloride from getting to the reaction center.

“We are essentially doubling up on ways to stop this chloride reaction,” Perryman said.

A home for hydrogen The ideal membrane system would perform three primary functions: separate hydrogen and oxygen gases from seawater; help move only the useful hydrogen and hydroxide ions while restricting other seawater ions; and help prevent undesired reactions. Capturing all three of these together is hard, and the team’s research is targeted toward exploring systems that can efficiently combine all three of these needs.

Specifically in their experiment, protons, which were the positive hydrogen ions, pass through one of the membrane layers to a place where they can be collected and turned into hydrogen gas by interacting with a negatively charged electrode. The second membrane in the system allows only negative ions, such as chloride, to travel through.

As an additional backstop, one membrane layer contains negatively charged groups that are fixed to the membrane, which makes it harder for other negatively charged ions, like chloride, to move to places where they shouldn’t be, said Daniela Marin, a Stanford graduate student in chemical engineering and co-author. The negatively-charged membrane proved to be highly efficient in blocking almost all of the chloride ions in the team’s experiments, and their system operated without generating toxic byproducts like bleach and chlorine.

Along with designing a seawater-to-hydrogen membrane system, the study also provides a better general understanding of how seawater ions move through membranes, the researchers said. This knowledge can help scientists design stronger membranes for other applications as well, such as producing oxygen gas.

“There is also some interest in using electrolysis to produce oxygen,” Marin said. “Understanding ion flow and conversion in our bipolar membrane system is critical for this effort, too. Along with producing hydrogen in our experiment, we also showed how to use the bipolar membrane to generate oxygen gas.”

Next, the team plans to improve their electrodes and membranes by building them with materials that are more abundant and easily mined. This design improvement could make the electrolysis system easier to scale to a size needed to generate hydrogen for energy-intensive activities, like the transportation sector, the team said.

The researchers also hope to take their electrolysis cells to SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), where they can study the atomic structure of catalysts and membranes using the facility’s intense X-rays.

“The future is bright for green hydrogen technologies,” said Thomas Jaramillo, professor at SLAC and Stanford and director of SUNCAT. “The fundamental insights we are gaining are key to informing future innovations for improved performance, durability, and scalability of this technology.”

Reference: “Hydrogen production with seawater-resilient bipolar membrane electrolyzers” by Daniela H. Marin, Joseph T. Perryman, McKenzie A. Hubert, Grace A. Lindquist, Lihaokun Chen, Ashton M. Aleman, Gaurav A. Kamat, Valerie A. Niemann, Michaela Burke Stevens, Yagya N. Regmi, Shannon W. Boettcher, Adam C. Nielander and Thomas F. Jaramillo, 11 April 2023, Joule. DOI: 10.1016/j.joule.2023.03.005

This project is supported by the U.S. Office of Naval Research; the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability Accelerator; the DOE’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division through the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, a SLAC-Stanford joint institute; and the DOE’s Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fuel Cell Technologies Office.

“Hydrogen gas is a low-carbon fuel”

The stupid hurts...

And they only need a few trillion of tax dollars to make it work.

But the tiny solar panel is a 10 Mega-watt solar panel (not currently available, but commercially available just around the corner).

I've only worked around the edges of industrial electrolytic processes so am far from an expert. That said… I've worked around aspects of very large operations to produce chorine and sodium hydroxide from saturated brine and magnesium from seawater.

As a guess…. The ideal way to use this double membrane could be to colocate with magnesium production.

Front end feed purification would likely be needed. Large amounts of land area are needed for these unit operations.

Some millions (or billions at a national scale) of gallons per minute of seawater are going to be required. Huge amounts of sodium hydroxide are required to raise the pH thus precipitating out hardness elements. Then, hydrochloric acid is likely used to lower pH so you can strip carbon dioxide (global warming!) from the water.

The electricity requirements are very substantial. Dozens if not more (LOTs more) large power plants will be required. This is of the baseline thermal or nuclear type, not unicorn fart variety.

There will be a small amount of hazardous waste produced in the form of chlorinated hydrocarbons. These are removed and sent to hazardous waste incinerators or perhaps fuel in cement kilns.

There are just a handful of companies worldwide that work at the largest scale of these kinds of production operations.

Yeah, turning seawater into fuel is not a trick. Turning seawater into fuel in a process that isn’t a net energy drain would be a trick.

This is without a doubt the stupidest article I have EVER seen published. Everyone involved with it from the first letter to the clown who hit “Enter” to upload it to the server should be kicked in the nuts.

This is “IFL Science” level bullshittery. Even Neil Degrasse-tyson would keep his distance from this junk.

“If I remember my chemistry propane is C3H8 and nat gas is C2H4”

We might both be half right. Looked up “natural gas” and it said it’s a mixture of methane (CH4) and other hydrocarbons.

I doubt that hydrogen will be a common transportation fuel. Nuclear is my favorite. Water power is super but don’t think there are enough dammable lakes.

“If I remember my chemistry propane is C3H8 and nat gas is C2H4”

We might both be half right. Looked up “natural gas” and it said it’s a mixture of methane (CH4) and other hydrocarbons.

I doubt that hydrogen will be a common transportation fuel. Nuclear is my favorite. Water power is super but don’t think there are enough dammable lakes.

“Insane in the membrane...”

I much prefer to run my boat on diesel, no fire problem or explosion.

ENTROPY RULES.

Technically that’s the 2nd Law. 1st Law says the best you can do is break even, 2nd says you can’t even do that.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.