Posted on 01/01/2017 6:44:11 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

January 6. Have been honestly trying hard all the evening, and for the tenth time, at least, to frame answers to the printed interrogatories as to improvements in Columbia College served on the trustees individually by the Omnibus Committee “On the course.” It’s very difficult to do it satisfactorily or at all, and unless I give up the job in despair, it will cost me a month’s work and probably never be read by anyone of the committee. Many of the questions are so badly drawn that they can be answered only by an essay on education. But I’ll return to the work. Ellie is good for at least another hour at Moses H’s, it being only half-past twelve. “A fool (that’s Gouverneur Ogden) can ask more questions in a minute than a wise man (that’s me) can answer in a day.”

The Diary of George Templeton Strong, Edited by Allan Nevins and Milton Halsey Thomas

I learned the original lyrics while a 13 or 14 year old kid at Culver Military Academy. One of the troopers in my squadron was from Kentucky, and liked to sing the original lyrics while we were riding.

Snarky devil, isn’t he? But I sympathize.

h: "Which was clearly illustrated by the Stephen Foster in the second Iine of the original lyrics to 'My Old Kentucky Home.' "

I too had to look that one up, did not remember it from my youth.

But we should be clear that -- South, North, East or West -- only a fortunate few enjoyed a "leisured" life, 10% at most.

Everybody else -- white, black, Native or mixed -- all worked as hard as their health & ambitions dictated.

Old Kentucky Home tells us of a farm which failed, its, ahem, workers sold down the river for more backbreaking jobs.

Sure Kentucky is a beautiful state, but Garden of Eden?

Not really.

... all worked as hard as their health & ambitions dictated.

It is the latter element that was less typical in the South (they say). As a rule, they simply were not as ambitious for gain or advancement. It's all in "Albion's Seed," among other sources.

I think more recent scholarship throws such assumptions into question, and paints a picture of the South as highly energetic, ambitious, risk-taking and most strikingly, prosperous.

Yes, Southerners had fewer miles of railroad and fewer factories than the North, but only the North and parts of England exceeded them in that.

And no nation, including the North exceeded the Deep Cotton South in (white) wealth per-capita, when you consider the accumulated value of slaves.

One thing antebellum Southerners did freely admit was their own unsuitability for field work in their hot summer climate.

That's why, they said, they needed & could not do without African slaves.

Bottom line: from, say 1830 to 1860 Southern growth in population and economics compared to that of the North, when you equate Southern plantations with Northern factories.

And, as many FR posters have noted, by 1860 at least half and maybe 3/4, of US exports (depending on how, exactly, you count it) were products of the South.

So the South was more dynamic that perhaps people like your Thomas Sowell give them credit for.

The less typical industriousness of the south has been attributed to a number of public health issues that were resolved in the first half of the 20th Century. However, the real impediment to industrialization and commercialization of the southern economy was the climate. This was not addressed until the widespread availability of air conditioning in the 1970s. It is no coincidence that the rise of the south took place about that time.

I think equating factories with plantations and industrial capital with slaves is what we call a “category error.” They are different economic units. The more useful comparisons would be of Northern vs. Southern farms and Northern vs. Southern factories. Compare output, productivity of capital and labor inputs, production diversity, etc.

I wasn’t trying to equate the northern and southern economies. Your points are well taken in the comparison of slave vs. non-slave economics. My point was rather that there were incidental factors that contributed to the lack of industrial progress of the south. In comparison to the north, the south languished economically long after the abolition of slavery. One of the factors was climate; it was just too hot and muggy.

Before and during World War 2, the south was a reservoir of labor for northern industrial plants. That reservoir migrated north, and was both blacks and whites. While you have the black migration recently celebrated in books such as “Warmth of Other Suns,” white migration was just as important. For example, Firestone built a war plant in one of our local communities. The labor force was largely obtained by shipping people here from one rural Virginia county along the Kentucky border. Those people gave the community much of its hillbilly character. There is a reason they built the factory here in Indiana instead of where the labor was.

Develop widespread air conditioning in the 1970s, and voila! You have economic and industrial activity in the south.

Back in the bad old days my Indiana relatives were very disparaging of those they called “Kentuckians” - white Southerners who moved North to work in the plants.

Maybe there was something to the slavers’ suspicions about Governor Geary. After statehood, a county was named for him. Interesting bit of trivia: the county was originally named Davis County, for Jefferson Davis.

I was mainly addressing BroJoeK's statistics, which conflated agriculture and industry in a way that is less than useful. One compares agriculture with agriculture and industry with industry, regardless of whether the labor is free, slave, or a mix. (Also, I was using my phone, which makes it nearly impossible to say anything sensible.)

The diet, disease, and climate issues certainly affect productivity, independent of everything else. On the other hand, poor nutrition was to some extent a result of culture, reflecting both the emphasis on export-cotton production and the preponderance of corn as a staple food crop. It's possible to grow a fine, healthy diet in the South, as our present situation demonstrates.

I learned from my recent reading (Bio of Jefferson Davis, IIRC) that this was also true to some extent during the Civil War. Some poor whites, trying to cope with hard times made much worse by the war, figured that they could do better for their families by going north to find a job than by enlisting or being conscripted into the confederate army.

Very interesting.

I’m finally reading “The Red Badge of Courage.” I picked it off the shelf the other day when I was looking for something small to read on the elliptical trainer. Another week at the gym, and I should finish it!

I think we have to draw a sharp distinction between antebellum and post-war Southern economy.

Post-war everything you say is doubtless true.

Antebellum is a much different story.

Perhaps I can explain it this way:

In 1860 the US Deep South was the Saudi Arabia of cotton -- the world's largest, cheapest and most profitable mass producer of the most important global commodity, industrial grade cotton, and had been for decades.

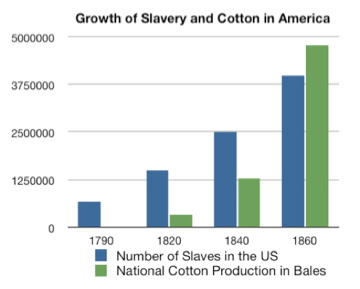

Since the 1840s the world had beaten many paths to the South's doors, demanding ever more cotton at ever higher prices, and the Southern economy grew like crazy to meet the demands.

And along with its rapidly expanding economy grew its population and prosperity.

Yes, Tara from Gone With the Wind was somewhat above "average", but it certainly represented Southern aspirations.

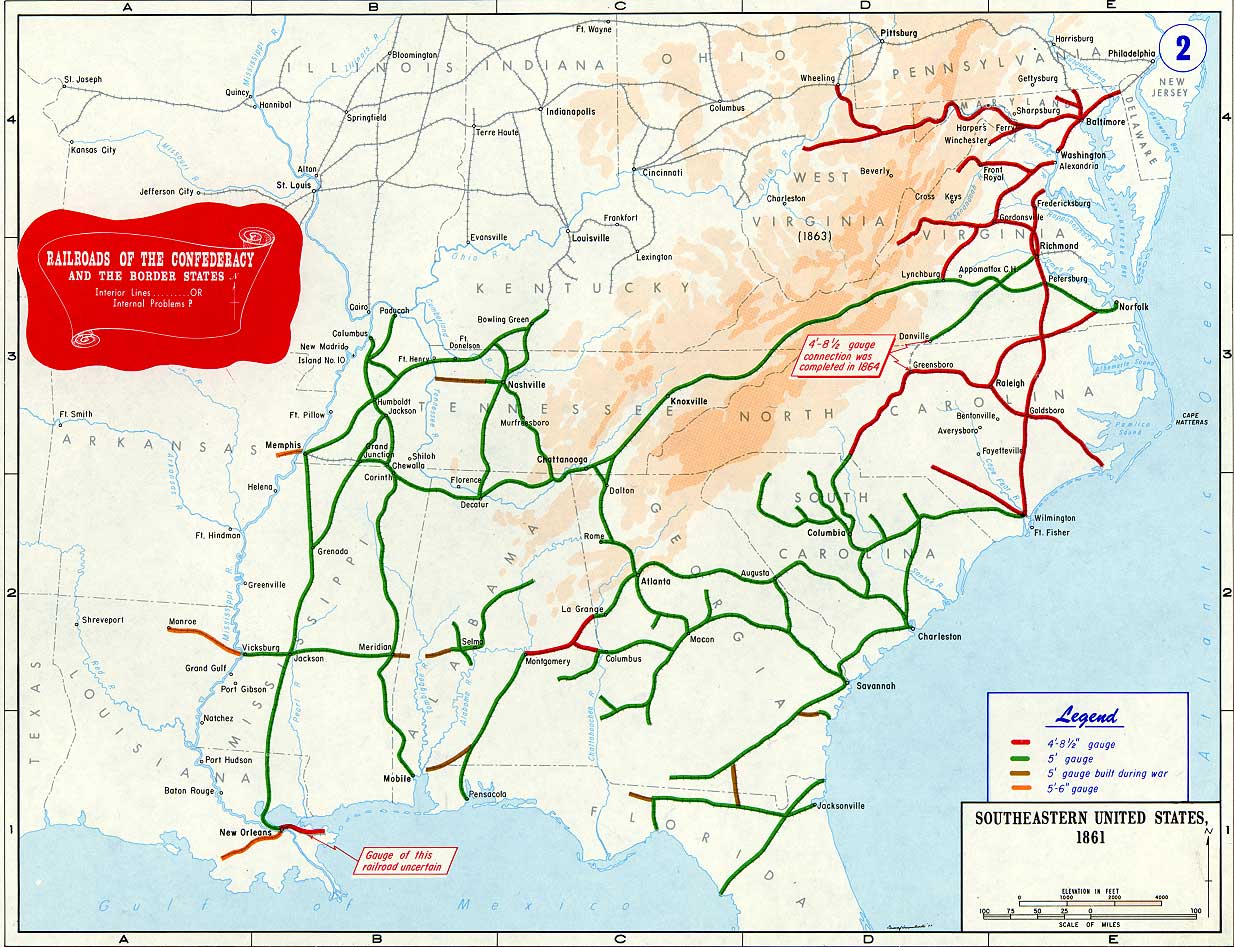

Note that Southern railroads were intended foremost to take product to ports for export, and Southern products represented at least half (some claim 3/4) of total US exports:

So far from being some kind of backwater, in 1860 the South was a prime driver behind overall US prosperity.

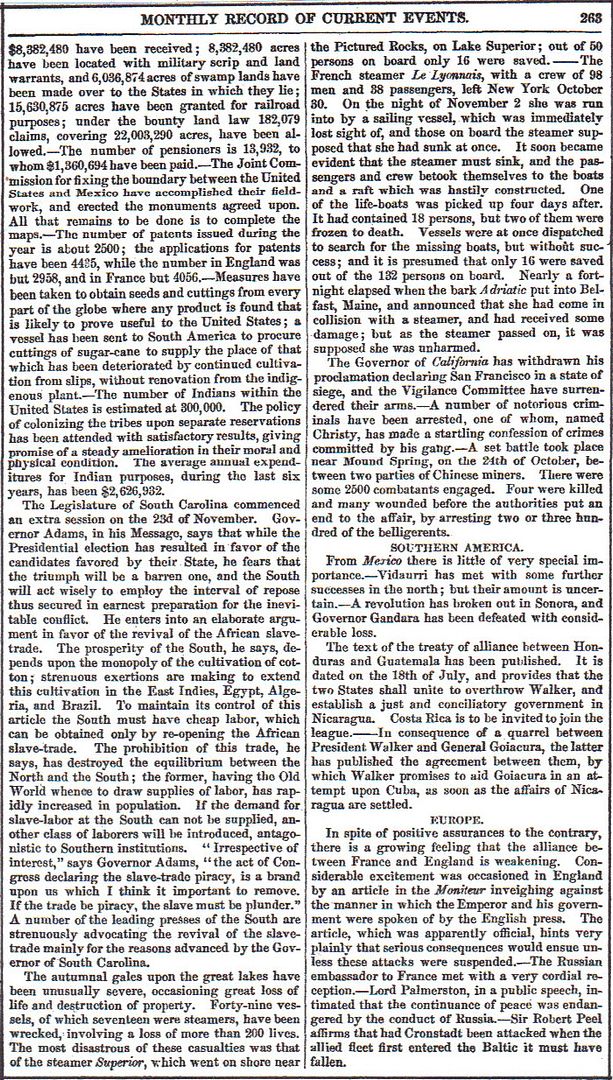

You can also see slave ownership declined dramatically the farther west you went in Texas.

Kansas was not suitable for plantation agriculture or the ownership of slaves in any numbers. The only reason the slavers wanted it was to get two more Senators.

Sure, but the claim is made, erroneously, that in 1860 the US South was some kind of "backwater", less advanced, less industrious and less prosperous than Northerners.

I'm here to argue that simply is not the case.

In fact, by 1860 Southerners had simply responded for decades to the most compelling economic opportunities available to them: producing cotton, tobacco, rice, sugar and other agricultural products for global export, including "export" to Northern states.

These exports were hugely significant to not only the Southern economy, but also the entire US economy.

That's because they paid for the imports on which our Federal Government collected tariffs, which tariffs were over 90% of its income at the time.

So exports helped make Southerners, especially Deep South cotton producers, the most prosperous people on earth at the time, measurably better off than their average Northern cousins -- if you consider their huge investments in slaves.

Let me suggest, if you fail to grasp the significance of antebellum Southern prosperity, then you have no clue as to why they were so, so adamant to protect, defend and expand it.

I know the following is still a few years in the future, but perfectly expresses how most Deep South Southerners felt throughout the antebellum period:

True, and it reflects a point many are confused about -- in 1857 was slavery dying out, as some claim, or was it growing and expanding?

The answer is: both, and the former because of the latter.

The reason: great drivers of slavery's profitability, growth and expansion were growing US cotton exports.

To meet the world's insatiable demand Southerners continually expanded the range and acreage devoted to cotton, using ever more slaves and driving up slave prices.

These high prices made slavery unprofitable in non-cotton regions, especially those Border South states like Delaware & Maryland where it was a short walk to freedom in the North.

So in Delaware and Maryland, numbers of slaves were declining in 1860 and it could be argued that at some point they would abolish slavery itself, just as Northern states did.

Border State Missouri was similar in having relatively fewer jobs for slaves and being closer to free states.

So in Missouri the slave population was still growing, slowly.

However, at the same time there was a huge influx of abolitionist immigrants, especially from Germany, and they reduced the slave population (and slave holders) as a percentage of the total, such that secession in 1861 was never approved by voters.

1860 Missouri slave percentages, by county:

BroJoeK, I can’t tell whether those percentages are 1.0-2.0% or 10-20%.

My late father was from She(lby) County, near the top right. It is purple on your map. That horizontal band across the state is interesting. It must reflect some geographical feature.

Certainly the larger, beginning at less than 10% (green) and growing to over 30% (red).

"That horizontal band across the state is interesting. It must reflect some geographical feature."

Yes, as colorado tanker mentioned above: "The darker region north of the Missouri River was known as Little Dixie and had some smaller scale plantation agriculture."

That's the Missouri river you see.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.