"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

Posted on 11/21/2015 11:35:55 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

Before when free-soil men invoked the right of revolution in defense of their political rights, proslavery men condemned them for defying the legitimate government. But proslavery men feared the loss of their right to own slaves as much as free soilers feared the loss of the right to exclude slavery.

At Hickory Point, [Kansas] a squabble over land claims ignited these political quarrels. A settler named Franklin M. Coleman had been squatting on land abandoned by some Hoosiers, who subsequently sold the claim to Jacob Branson, another Hoosier. In late 1854, when Branson informed Coleman of his legal claim and attempted to move into Coleman’s house, Coleman held him off with a gun. A group of arbitrators later awarded part of the claim to Branson, but the boundaries between his land and Coleman’s were not determined. Branson invited in other men, including a young Ohioan named Charles W. Dow. Branson belonged to the free-state militia, a connection he used to intimidate Coleman, although Branson later testified that there had been no problems between Dow and Coleman – until the day of Dow’s murder.

On the morning of November 21, 1855, Dow went to the blacksmith shop at Hickory Point to have a wagon skein and lynchpin mended. While there he argued with one of Coleman’s friends, but left unharmed. As he walked away, he passed Coleman on the road. Coleman snapped a cap at him. When Dow turned around, he received a charge of buckshot in the chest and died immediately. His body lay in the road until Branson recovered it four hours later. Coleman claimed that Dow had threateningly raised the wagon skein (a two-foot piece of iron) as they argued over their claim dispute, forcing him to act in self-defense. Fearing that he could not get fair treatment at the free-state settlement of Hickory Point, Coleman and his family fled to Missouri.

Nicole Etcheson, “Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Eraâ€

You may be aware of the letter that the Continental Congress sent to King George pledging their desire to preserve their union with England and to settle their differences peaceably. The summer of 1775, after Lexington and Concord. King George didn't buy it and declared the Colonials to be rebels and traitors.

I'd put the wording of the Resolves in the same vein. An attempt to smooth over some very real differences when conflict was already baked into the cake. George Washington didn't buy the Resolves desire to preserve the union and could see that the Compact Theory of Jefferson and Madison implied nullification and probably disunion.

Thank you for posting this, and I look forward to further excerpts. From what little I know of him Frederick Douglass was a great man, someone who truly spoke truth to power.

I don’t see those two as equivalent. It was a different set of circumstances. This was a case of trying establish the limits of a new constitutional republic, not try to petition a parliamentary monarch across an ocean for a return of the status quo.

The formation of this new Constitution was a series of compromises in and of itself, and incidents like the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, McCulloch v. Maryland and other proceedings were all part of the growing pains of trying to establish the limits of the new Constitution. Testing the limits is a far cry from giving up on it which I don’t see the 1798-9 resolutions suggesting.

"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

“Whenever I hear any one arguing for slavery I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.”

— Abraham Lincoln, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume VIII, “Speech to One Hundred Fortieth Indiana Regiment” (March 17, 1865), p. 361.

Reading further in Frederick Douglass’ memoir, I found him to be strangely unmoved by slaveholders’ complaints about the infringement of their freedom and property rights pressed upon them by the abolitionists.

Makes me wonder if the master wanted the poor girl for himself. Being a young boy, Frederick probably wouldn’t have been privy to that kind of encounter.

I too wondered if the master was jealous? In most such situations, I would expect the object of fury to be the male and that he would be sold off in a far away market. That he apparently suffered no mistreatment makes me wonder if he was the object of the masters lusts and the master was furious at the woman for "spoiling" his favorite boy?

All other explanations I could think of involved fantasies unfulfilled due to repression and/or ED.

What a shock.

/s

There are two different owners in this situation. Esther is owned by “Captain Anthony,” as is the narrator, while her paramour is owned by “Col. Lloyd.”

Thanks. Something was telling me as I typed the original comment that I should re-read the account.

One thing I didn't pick up on in the original reading is that "Captain Anthony" was something of a slave owning sharecropper to Col. Lloyd. To help make ends meet, Captain Anthony would occasionally sell one of his slaves.

Anthony either sold his land ownings, lost them, or never had any and his slaves were acquired as an inheritance.

Whatever the case, Capt. Anthony couldn't make it on his own, he had to work for Col. Lloyd.

Douglas doesn't tell us much but in modern parlance, Captain Anthony seemed to have a bit of autism going on.

Yes, it sounded like Captain Anthony had some mental issues. Might have been autism, or some form of dementia, maybe that kind you get from a life of heavy drinking.

I suppose I’m reacting to “fake but accurate” modern journalism when I wonder how much of Douglass’s narrative is factually true. On the other hand, 19th century journalism wasn’t overly concerned with absolute factual truthiness, when there was a story to sell or an agenda to promote ...

"The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," by Frederick Douglass, (1892 edition)

After my last post, I went back and reread ch 1-5. Capt. Anthony is described in Ch1 as owning several farms which raises the question, why wasn't Capt. Anthony living on his own property rather than working for Col. Lloyd and periodically selling one of his (Anthony's) slaves in order to help make ends meet?

Do property records exist supporting such claim of multiple farm ownership by Capt. Anthony, or was Anthony also a liar attempting to boost his perceived social-economic standing amongst the slaves he oversaw?

I suppose I’m reacting to “fake but accurate†modern journalism when I wonder how much of Douglass’s narrative is factually true. On the other hand, 19th century journalism wasn’t overly concerned with absolute factual truthiness, when there was a story to sell or an agenda to promote ..

Interesting question for which I do not know the answer.

Another possibility regarding the unclearness about the property is that the young Douglass could have misunderstood something he overheard.

That is also possible. Surely someone has already researched this matter and published their findings.

There’s probably a Master’s thesis on it ;-).

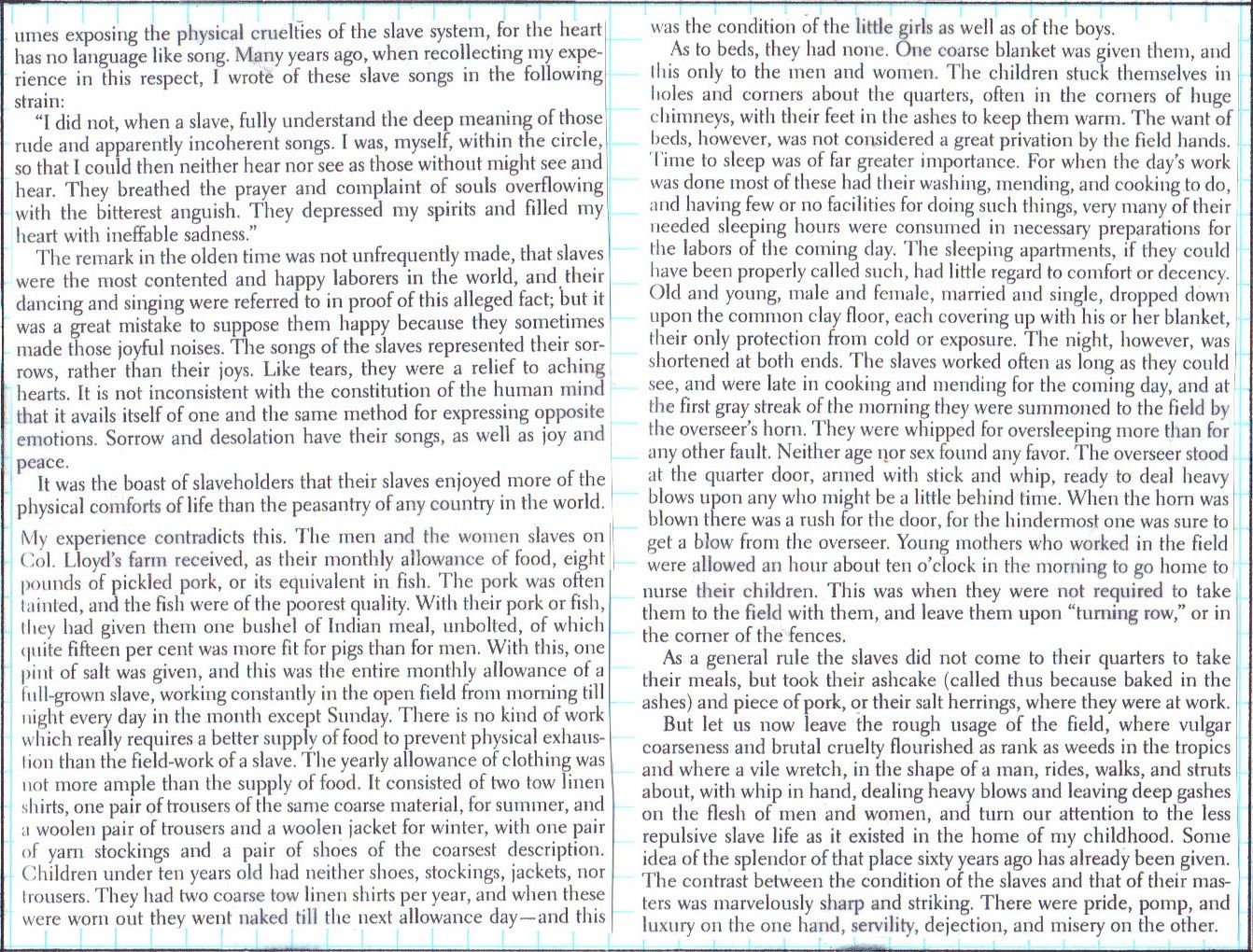

Very interesting information in the next excerpt about the economic conditions for the slaves.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.