Posted on 11/16/2010 4:39:08 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1940/nov40/f16nov40.htm

German transports fail to evade Royal Navy

Saturday, November 16, 1940 www.onwar.com

In Mexico... Three German cargo ships leave the port of Tampico but fail to evade the British blockade. The Phrygia is scuttled while the Idarwald and Rhein return to Tampico.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/16.htm

November 16th, 1940

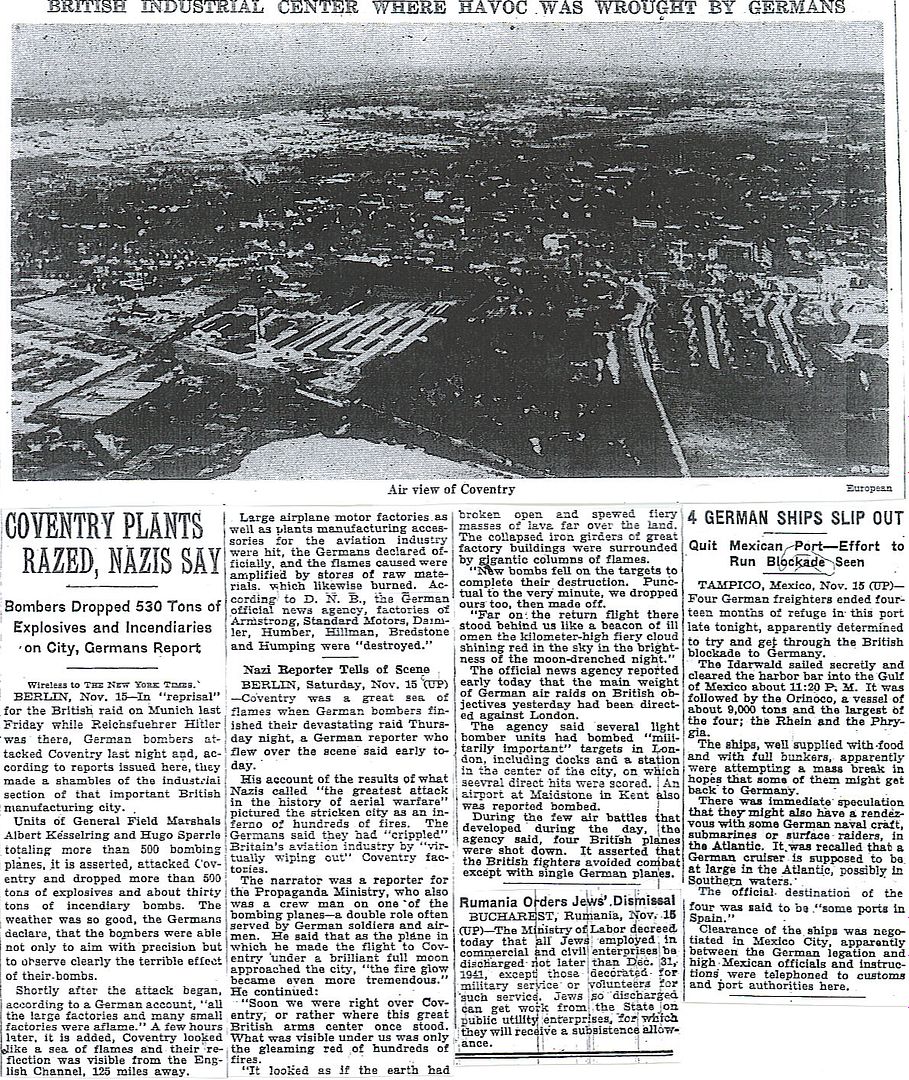

UNITED KINGDOM: Coventry: The Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, escorts King George VI through the ruins of the city. The Mayor remarks: “We’ve always wanted a site for a new civic centre, and now we have it.”

RAF Bomber Command: 2 Group. Five crews of 105 Squadron ( Blenheim) hit the airfields at Hingene, Evere, Duerne and Vucht. One aircraft is lost to ground fire.

ASW trawler HMS Arsenal sunk on the Clyde after colliding with destroyer ORP Burza.

Corvette HMS Pimpernel launched.

Light cruiser HMS Jamaica launched.

Minesweeping trawler HMS Arran launched.

Corvette HMS Bryony laid down.

Corvette KNS Montbretia (ex-HMS Montbretia) laid down.

Destroyer HMS Cotswold commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

The Canada Steamships merchantman Sherbrooke (2,052 GRT) was damaged when she was attacked by Luftwaffe bombers in the North Sea, off Orfordness. There is no record of casualties in this incident. (Dave Shirlaw)

ENGLISH CHANNEL: Submarine HMS Swordfish, setting out on bay of Biscay patrol, strikes an enemy mine off the Isle of Wight and sinks.

GERMANY: U-147, U-148, U-751 launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

GREECE: 3,500 British military personnel have been ferried from Alexandria to Piraeus.

AUSTRALIA: Minesweeper HMAS Gouldburn launched.

Minesweeper HMAS Townsville laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

CANADA: Corvettes HMCS Camrose and Sorel launched Sorel, Province of Quebec. (Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.A.: Minesweeper USS Osprey commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN:

U-137 sank SS Planter.

U-65 sank SS Fabian in Convoy OB-234. U-65 provided two shipwrecked survivors of sunken Fabian with medical aid, food and water. (Dave Shirlaw)

http://worldwar2daybyday.blogspot.com/

Day 443 November 16, 1940

In Albania, Greek 3rd Army Corps breaks through the defenses of Italian 9th Army near Korçë in the Morava Mountains. 500 miles away, residents of the town of Menton on the French Riviera 1 mile from the Italian border mock their Italian neighbors with a sign “This is French territory. Greeks, do not advance any further”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heroes%27_Cemetery

250 miles Southwest of Sierra Leone, U-65 sinks British SS Fabian with a torpedo and the deckgun (6 crew lost). 33 survivors are questioned then given food and water by the Germans, who also treat 2 wounded men, and then picked up by British tanker British Statesman and landed at Freetown.

30 miles North of Ireland at 8.15 PM, U-137 sinks British SS Planter (killing 12 crew and 1 passenger, a displaced seaman hitching a ride home to Britain). 59 crew and 1 gunner are picked up by destroyer HMS Clare and landed at Liverpool. http://www.uboat.net/allies/merchants/ships/656.html

British anti-submarine trawler HMT Arsenal sinks after colliding with Polish destroyer Burza 4 miles south of the village of Toward in the Clyde River estuary, Scotland. Arsenal’s crew is rescued by destroyer HMS Arrow and tug Superman. Arsenal’s depth charges explode, damaging HMS Arrow (under repair in the Clyde until January 14 1941). Burza is also repaired in the Clyde, completed January 27 1941.

Coventry was sacrificed. ENIGMA intercepts indicated that the Luftwaffe had targeted Coventry. Rather than let the Nazi high command know that their ENIGMA coding system had been compromised, Churchill elected not to alert the RAF or civil authorities in Coventry.

The tunnel cost $58 million and took just over four years from ground-breaking to opening ceremony. Now, on the West Side they are doing repair work on one of the approaches to the Holland Tunnel. This work is expected to to take three to five years. I don't know what the projected cost is but it's a sure bet that it will be a lot more than $58 mil even after adjusting for inflation.

ML/NJ

I always thought of the Coventry raid as happening during the height of the Battle of Britain, back during the days of August and September. Even though the Germans are now gearing up to attack the USSR, it appears the Luftwaffe is still fully committed against Britain, if mostly at night.

Didn’t a lot more than 1,000 die in Coventry that night?

PzLdr posted about this the day before yesterday. Vanders9 responded that "latest historical thought" was that Churchill might not have known Coventry was targeted. It would be useful if someone provided support for one side or the other on this question.

Another reason I shed no tears over Dresden.

The worldwar2day-by-day.blogspot entry for that day says 600 dead and 1,000 injured.

Not likely, Churchill was very keen about ENIGMA and wanted to see all the significant intercepts.

From: http://www.historiccoventry.co.uk/blitz/myths.php

Did Churchill leave us to be bombed?

In the 1970’s, after information about some of our wartime secrets had been released, some writers used this new found knowledge to sell books based upon a conspiracy theory. They alleged that certain authorities knew in advance that Coventry was to be targeted for a heavy raid, but in order to protect ULTRA (our deciphering of German codes using the captured ‘Enigma’ machine or other methods) our city was left to burn. Put simply, the conspiracy theorists tried to have us believe that if the citizens of Coventry had been given advance warning, then the Germans would have suspected that we’d broken their secret radio codes.

The tower & spire - standing strong

I’ve attempted on page 4 to summarise the situation regarding how much we knew about the enemy’s radio direction technology. However, as can be surmised from this, the X-Gerat radio beams were detected by our planes carrying radio measuring equipment, and the Germans would have been fully aware that we could simply fly across the signal path to detect such beams. Therefore, ULTRA was in no way compromised by letting the Germans find out that we were attempting to jam their signals.

But still the conspiracy continued - based mainly on the fact that our use of ULTRA information had forewarned British Intelligence and Prime Minister Winston Churchill about the raid, but allegedely purposely not informed Coventry. As page 4 hopefully also shows, decrypted codes were indeed used, but were still inconclusive about the intended target.

Surprisingly, one of the people directly involved in message decryption, Group Captain F. W. Winterbotham, was also one of those who helped to spread the conspiracy that Coventry was ‘left to burn’. In the 1970s he wrote an account purely from memory, stating that the name ‘Coventry’ actually came through in clear type from a German message at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of the 14th. Not only is it unlikely in the extreme that the Germans would be so lax with their coding, but R. V. Jones, the head of Scientific Intelligence, and through whom all messages had to pass, states categorically that no message whatsoever was received that hinted at Coventry as the target.

Wolverhampton and Birmingham had been deduced from the intelligence received, but rather than Coventry as the third target, some sources actually believed that London was the other possible raid target for that night of the full moon in mid-November. ULTRA, in fact, had been of extremely limited value in this particular case.

The Prime Minister certainly believed London to be that night’s target, and to back this up, his movements on the afternoon of the 14th were recorded in the diary of a friend and close colleague at Number 10, Sir John Colville. That afternoon, Churchill set off for his country house in Ditchley, Oxfordshire, where he regularly stayed instead of Chequers on moonlit nights. During the journey he opened his yellow ‘Ultra’ box and quickly learned that the heaviest bombing raid yet was about to be launched, but on a target as yet unspecified. The additional information about the detecting of the X-Gerat radio signal being aligned on Coventry was not yet available to him. Convinced that the raid was to be on London, he ordered his driver to return him to Downing Street, whereby he ordered his two colleagues into the deep air-raid shelter. Their young lives, he told them, were too valuable to our country’s future. He then went up onto the Air Ministry roof with one older colleague to await the raiders arrival.

Those, to me, are not the actions of a Prime Minister who suspected that there was going to be a raid on Coventry.

A particularly detailed and authoritative account explaining the contradictory tales of ‘Churchill and Coventry’s bombing’ can be found on The Churchill Centre website.

From the Churchill Centre Website: http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/myths/myths/he-let-coventry-burn

Churchill Let Coventry Burn To Protect His Secret Intelligence | Print |

Peter J. McIver

Mr. McIver, of Nuneaton, Warwickshire, penned this article eighteen years ago in Finest Hour 41. We have brought it up to date by adding or quoting additional, most recently published material.

For twenty years, most recently in a piece by Christopher Hitchens in The Atlantic Monthly, it has become a matter of accepted fact that on the night of 14-15 November 1940, rather than compromise a decisive source of intelligence, Winston Churchill left the city of Coventry to the mercies of the German Air force.

This story has appeared in many books, articles and letters to the press, but its origins date back over a quarter century to three books, by F. W. Winterbotham, Anthony Cave Brown, and William Stevenson.

The originator of the “prior warning” theory was former RAF Group Captain F. W. Winterbotham in The Ultra Secret (New York: Harper & Row, 1974). This was the first book to reveal that the Allies had broken the German codes‹a fact that was until then a closely guarded official secret.

According to Winterbotham, who wrote entirely from memory, the name Coventry came through in clear type on a decrypt of German messages (codenamed “Boniface,” later “Ultra”) at 3PM on 14 November, the afternoon before the raid, and Winterbotham himself immediately telephoned the news to one of Churchill’s private secretaries in Downing Street (The Ultra Secret 82-84).

Much the same tale was told by Cave Brown in his two-volume work, Bodyguard of Lies (New York: Harper & Row, 1974). But Cave Brown wrote that Churchill had the message a full two days ahead of time. The Coventry raid, he wrote, was one of three under the code name “Einheitopreis,” against Midlands cities coded “Umbrella” for Birmingham, “All One Piece” for Wolverhampton, and “Corn” for Coventry (Bodyguard of Lies I:38-44).

Picking up on these 1974 books, William Stevenson in A Man Called Intrepid (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1976), wrote that the Germans sent the order to destroy Coventry in the second week of November. Unlike previous “Boniface” messages, which had always given the name of the target in code, this message gave the name “Coventry” in clear type. Thus, wrote Stevenson, within minutes of the order being given, it was placed in front of the Prime Minister. Faced with the prospect of leaving the people of Coventry to die or evacuating them, Churchill turned to Sir William Stephenson (”Intrepid”), who advised that “Boniface” was too valuable a source of intelligence to risk. By evacuating the city, the Prime Minister would expose the source and endanger its usefulness in the future - so “Intrepid” told Churchill to leave Coventry to burn and its people to their fate.

While at first glance all three writers seem to agree, there are considerable differences between them. For example, Winterbotham claimed that he telephoned the information to Downing Street, while Stevenson said the news was given to Churchill by “Intrepid.” Cave Brown asserted that Churchill knew about the raid forty-eight hours in advance; Winterbotham said Coventry was identified as the target only a few hours before the attack.

All three authors cannot be correct, though as I will show, all are certainly wrong. Cave Brown’s account has several errors independent from the differences with the other writers. The code name for the Wolverhampton raid was “All One Price,” not “All One Piece.” Its significance was not lost on the Air Ministry, which quickly realized that it referred to the “Everything at One Price” sales slogan of Woolworth & Co. - ergo Wolverhampton. “Umbrella,” the Ministry concluded, meant Birmingham because Neville Chamberlain, a famous carrier of umbrellas, was a former mayor of Birmingham. But nothing connected “Corn” with Coventry.

By mid-November the Air Ministry had learned that the Germans were having difficulties with their Knickebein radio direction beam, used to direct bombers to their targets; it seemed likely that they would use the more accurate X-Gerat system installed in Luftwaffe unit K. GR100, which would act as a pathfinding fire raiser for less experienced pilots. The Air Ministry reached this conclusion from reports that the Germans had been attacking isolated targets in England with flares instead of bombs.

On 11 November the Air Ministry decoded a German message referring to a raid codenamed “Moonlight Sonata.” This was the message in which the word “Corn” first appeared. Because of where the word appeared in the message Dr. R. V. Jones, one of the Air Ministry scientists, concluded that “Corn” referred not to a target but to the appearance of radar screens when jamming was present. According to Jones’s book, Most Secret War, aka The Wizard War (1978, 201), the code name “Moonlight Sonata” was believed to mean that the raid would take place on a night of a full moon, indicating the period 15-20 November. “Sonata” suggested a three-part operation; based on their knowledge of Luftwaffe guidance systems, the Ministry concluded that the first part would be a fire-raiser, the other two parts normal bombing raids (Public Records Office AIR2/5238).

No one at the Air Ministry believed that “Sonata” referred to three separate nights. The 11 November decrypt referred to four targets, and mentioned that Marshal Goering himself had been involved in the planning, an indication of how important this particular raid was viewed in Berlin.

In an appreciation of this message, considering not only Goering’s involvement but other intelligence, the Air Ministry concluded that the four targets were in the south of England, particularly London. The other intelligence included a captured German map which marked four target areas, all in the south; and an interview with a prisoner of war suggesting that the Midlands cities were targets for a future raid unconnected with “Moonlight Sonata” (P.R.O. AIR2/5238).

In the early hours of 12 November, Dr. Jones received a decrypt of a new German message which indicated that there was to be a raid against Coventry, Wolverhampton, and Birmingham. But there was nothing in this new message to connect it with “Moonlight Sonata,” and no such connection was made (P.R.O. AIR20/2419). As early as the morning before the raid, the Air Ministry were still expecting a raid on London.

What of Winterbotham’s alleged telephone call to Downing Street at 3PM the afternoon of November 14th? Dr. Jones, who was given copies of all “Boniface” decrypts at the same time as Winterbotham, states that there was no such message. In his book, Jones recalled traveling home that night wondering where the raid was actually going to be!

What did Churchill know and when did he know it? The most succinct summary came from one of Churchill’s private secretaries, John Colville, in his book, The Churchillians (London, 1981), page 62:

All concerned with the information gleaned from the intercepted German signals were conscious that German suspicions must not be aroused for the sake of ephemeral advantages. In the case of the Coventry raid no dilemma arose, for until the German directional beam was turned on the doomed city nobody knew where the great raid would be. Certainly the Prime Minister did not. The German signals referred to a major operation with the code name “Moonlight Sonata.” The usual “Boniface” secrecy in the Private Office had been lifted on this occasion and during the afternoon before the raid I wrote in my diary (kept under lock and key at 10 Downing Street), “It is obviously some major air operation, but its exact destination the Air Ministry find it difficult to determine.”

That same afternoon, Thursday 14 November 1940, Churchill set off with [private secretary] John Martin for Ditchley, Mr. and Mrs. Ronald Tree’s house in Oxfordshire, generously made available to the Prime Minister once a month when the moon was full and the PM’s official residence, Chequers, was vulnerable. Just before Churchill left, word was received that “Moonlight Sonata” was likely to take place that night. In the car he opened his most recent yellow box and read the German signals in full. He immediately told the chauffeur to turn round, and went back to Downing Street.

On arrival he decided that due precautions must be taken, for he assumed the operation to be aimed at London and to be a more massive assault than had ever been made before. He ordered that the female staff be sent home before darkness fell. He packed John Peck and me off to dine and sleep in a sumptuous air-raid shelter prepared and equipped in Down Street underground station by the London Passenger Transport Board. They made it available to the Prime Minister as well as to their own executive. Churchill called it “the burrow,” but used it himself on only a few occasions.

John Peck and I dined apolaustically in “the burrow.” I commented, with a blend of gratification and disapproval, “Caviar (almost unobtainable in these days of restricted imports); Perrier Jouet 1928; 1865 brandy and excellent Havana cigars.” Meanwhile Churchill, impatient for the fireworks to start, made his way to the Air Ministry roof with John Martin and saw nothing. For on their way to Coventry, the raiders dropped no bombs on London.

There is not even the thinnest shred of truth in Group Captain Winterbotham’s story of Coventry. It is to be hoped that neither this incident nor a score of others with which Mr. Stevenson’s book about “Intrepid” is gaudily bedizened are ever used for the purpose of historical reference. To dispel such an unacceptable hazard is my excuse for this long digression.

Colville was not the first to reveal the truth. Former private secretary, John Martin, who had been with Churchill in London on the fateful night, awaiting the bombers that never came, recalled the facts in The Times on 28 August 1976, when the charge was first circulating. A quarter century later, Christopher Hitchens in The Atlantic wrote that no Churchill defender has ever challenged the story. Historians Norman Longmate, Ronald Levin, Harry Hensley, and David Stafford are just four historians who as early as 1979 explicitly dismissed the Coventry story for the nonsense it is.

Colville’s hopes were in vain. The Coventry lie hardily endures, probably forever, periodically resurrected and solemnly proclaimed by those who have convinced themselves of Churchill’s perfidy.

At this point Patton is in command of the 2nd Armored Division in Ft. Benning, GA. This is a temporary command at the moment, but I'm sure he will continue up the ladder. He has sent some correspondence to his friend Dwight Eisenhower in hopes of getting him over to Ft. Benning to serve with him. Here is the correspondence leading up to today's letter from "The Patton Papers".

Letter, Eisenhower to GSP, Jr., September 17, 1940.Dear George: Thanks a lot for your recent note; I am flattered by your suggestion that I come to your outfit. It would be great to be in the tanks once more, and even better to be associated with you again...

I suppose it's too much to hope that I could have a regiment in your division, because I'm still almost three years away from my colonelcy. But I think I could do a damn good job of commanding a regiment...

Anyway, if there's a chance of that kind of assignment, I'd be for it 100%. Will you write me again about it, so that I may know what you had in mind?Letter, GSP, Jr., to Eisenhower, October 1, 1940

It seems highly probable that I will get one of the next two armored divisions which we firmly believe will be created in January or February, depending on [tank] production. If I do, I shall ask for you either as Chief of Staff, which I should prefer, or as a regimental commander. You can tell me which you want, for no matter how we get together we will go PLACES.

If you get a better offer in the meantime, take it, as I can't be sure, but I hope we can get together. At the moment there is nothing in the brigade good enough for you. However, if you want to take a chance, I will ask for you now...

Hoping we are together in a long and BLOODY war.Letter, GSP, Jr., to Eisenhower, November 1, 1940

If I were you, I would apply for a transfer to the Armored Corps NOW...

If you apply for a transfer...say that you are an old tanker.

If you have any pull...use it for there will be 10 new generals in this corps pretty damned soon.And now here is today's response from Ike.

Letter, Eisenhower to GSP, Jr., November 16, 1940

I have already sent in a letter similar to the one you suggested...

One of the new corps commanders, down south, had asked for me as his Chief of Staff, but...it was turned down because I was so junior in rank...I am probably to be allowed to stay with troops. So I ought to be available and eligible for transfer when the time comes.

As an aside, Patton plans to take the 2d Armored on maneuvers in mid December. I'm betting this will make the press at least in Washington. I'm not sure about the NYT.

Thank you, Henkster. That is persuasive. I will take it over Hitchens in Atlantic.

Carlo D’Este’s “Patton: A Genius for War” is also pretty good.

For me, the bottom line is that even if Churchill “knew” Coventry was a target, I doubt he would have known until it was too late to warn the citizenry. I’m sure the Brits were getting all sorts of false leads from intelligence on where the Germans were bombing, so how much of the information could he have really trusted?

Also, even if he “knew” there was nothing he could have physically done to stop the raid. Britain’s night defenses at this time were pretty crude, and mostly concentrated around London anyway.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.