BBC Audio: Dyson and Clarke

Will life spread out from Earth to flourish in the cosmos? Freeman Dyson has always supported the idea, and with great persuasiveness. BBC Four has created an archive of interviews on its Web site, among which is a clip of Dyson discussing life’s variety and the imperative of broadening its range. The theoretical physicist, who played an important role in the development of the ‘atomic spaceship’ concept called Project Orion, doesn’t believe man’s role is simply to send the occasional astronaut out in what he calls ‘a metal can’ to look out a window.

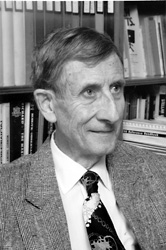

Image: Physicist Freeman Dyson, whose thoughts on life’s spread into the cosmos can be found in the BBC archives. Credit: Dartmouth College.

On the contrary, says Dyson in his interview, humans may have a shepherding role in building a permanent presence in space. Instead of ships full of scientists or colony vessels establishing a new human foothold, Dyson would argue that we humans are representative of a far larger pattern, the spread of living things in all their variety. Our major role is to assist. We’re talking here about migrating whole ecologies, but not as forced transplants on other worlds so much as adaptations that, over the eons, will assume their own unique identities:

If you look at the natural world, you see that everywhere life has gone, it brings tremendous variety. The natural world is beautiful just because there is such a tremendous variety of living creatures — trees, plants, butterflies, birds. And I think the same thing will happen in the universe at large. The universe will just be a far more beautiful and interesting place when life has taken it over.

Note the implication that life has not yet taken the universe over, perhaps a comment on the likelihood of success for our SETI efforts, if not an answer to the Fermi question. Dyson goes on:

Life will spread and diversify everywhere the same way it has on Earth. Life just has this ability to adapt itself to all sorts of different environments, and I don’t think it will stop at one planet, when you see the whole universe waiting there. That’s the reason I believe we shall go out there and take our plants and animals with us.

It’s a bold view and not one that fits readily within the constraints of governmental space programs. But where does it start? Although space settlements near Earth might seem to be the answer, Dyson told his BBC Four interviewer that he had no use for the kind of habitats envisioned by Gerard O’Neill, finding them far too bureaucratic. Instead, he opts for ‘little bands of adventurers’ going out, working at their own risk and with agendas set by themselves. The Mayflower’s voyage across the Atlantic is an analog to what he sees happening in space:

There’s a tremendous amount of stuff already floating around in orbit just waiting to be salvaged by anyone who’s brave enough to go and do it. There’s a lot of stuff on the Moon which is lying there. That’s the way the Mayflower people worked. They didn’t build the Mayflower; they rented it. I imagine we’ll do the same thing. We will certainly make us of whatever the government provides, and that kind of stuff can usually be had very cheap.

As always, Dyson is energizing, and you’ll want to check the BBC Four archive to hear these bits (thanks to Teleread for the tip on this), at the same time wondering, as I do, why interviews like these aren’t offered in their entirety there. But do poke around. Arthur C. Clarke also has some audio clips, including his recollections of Stanley Kubrick’s first contacts with him re 2001: A Space Odyssey. Clarke says he received a letter from Kubrick ‘out of the blue,’ saying he wanted to do the ‘proverbial good science fiction movie, and did I have any ideas.’ At the time, interestingly enough, Clarke not only didn’t know Kubrick, but had never heard of him.

Image: Arthur C. Clarke at work. Credit: Billye Cutchen.

We brainstormed, developing all sorts of ideas, and when we had a fairly clear concept of what we wanted to do, Stanley said ‘write the novel and I’ll derive the screenplay from it.’…There was feedback in both directions, because I would write part of the novel and he would write the screenplay, and I would read the screenplay and feed it back into the novel. Later on, when he was actually filming, I was still feeding things from the film back into the novel. Because the novel didn’t come out until well after the film.

The later novel 2010: Odyssey Two would be developed through an entirely different method. Clarke acknowledges that he had to write 2001: A Space Odyssey with film in mind, creating scenes that he could visualize on screen, but 2010 was written as simply the best novel he could create, and ‘if anyone wants to film it, good luck to them.’ I loved both films, but in many ways still find 2010 the more interesting, a view few of my friends share. In any case, give Clarke a listen, and be aware that in this BBC interview archive, you’ll also find Werner Heisenberg, not to mention literary figures of distinction from Graham Greene to Iris Murdoch, and a host of actors, musicians and philosophers.