|

Posted on 04/10/2006 8:17:15 PM PDT by bittygirl

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support. The FReeper Foxhole hopes to share with it's readers an open forum where we can learn about and discuss military history, military news and other topics of concern or interest to our readers be they Veteran's, Current Duty or anyone interested in what we have to offer. If the Foxhole makes someone appreciate, even a little, what others have sacrificed for us, then it has accomplished one of it's missions. We hope the Foxhole in some small way helps us to remember and honor those who came before us.

|

|

|

ROAD TRIP! Welcome Aboard the Battleship TEXAS In 1948, the Battleship TEXAS became the first battleship memorial museum in the U.S. That same year, on the anniversary of Texas Independence, the Texas was presented to the State of Texas and commissioned as the flagship of the Texas Navy. In 1983, the TEXAS was placed under the stewardship of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and is permanently anchored on the Buffalo Bayou and the busy Houston Ship Channel. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's 1,200-acre San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site consists of the Battleground, Monument and Battleship TEXAS. These sites are located within minutes of downtown Houston and a short distance to the beaches of Galveston Island. Millions of visitors come to this area each year to enjoy the mild coastal climate and cultural and sports activities. Students and visitors alike are most fortunate to be able to experience history first hand through living history at the San Jacinto Battleground and Battleship TEXAS.

Construction HistoryPhoto courtesy of Battleship TEXAS Archives

1914 Picture of Battleship TEXAS in it's original configuration. The TEXAS is the last of the battleships, patterned after HMS Dreadnought, that participated in World War (WW) I and II. She was launched on May 18, 1912 from Newport News, Virginia. When the USS TEXAS was commissioned on March 12,1914, she was the most powerful weapon in the world, the most complex product of an industrial nation just beginning to become a force in global events.

In 1916, TEXAS became the first U.S. battleship to mount antiaircraft guns and the first to control gunfire with directors and range-keepers, analog forerunners of today's computers. In 1919, TEXAS became the first U.S. battleship to launch an aircraft. In 1925, the TEXAS underwent major modifications. She was converted to oil-fired boilers, tripod masts and a single stack were added to the main deck, and the 5" guns that bristled from her sides were reduced in number and moved to the main deck to minimize problems with heavy weather and high seas. Blisters were also added as protection against torpedo attack. The TEXAS received the first commercial radar in the US Navy in 1939. New antiaircraft batteries, fire control and communication equipment allowed the ship to remain an aging but powerful unit in the US naval fleet. In 1940, Texas was designated flagship of US Atlantic Fleet. The First Marine Division was founded aboard the TEXAS early in 1941. April 21, 1948 the Texas was decommissioned. The TEXAS holds the distinguished designation of a National Historic Landmark and a National Mechanical Engineering Landmark. Naval History

After being commissioned the TEXAS proceeded almost immediately to Mexican waters where she joined the Special Service Squadron following the "Vera Cruz Incident." She returned to the Atlantic Fleet operations in the fall of 1914, after the Mexican crisis was resolved. After the US entered WW I, she spent the year 1917 training gun crews for merchant ships that were often attacked by gunfire from surfaced submarines. TEXAS joined the 6th Battle Squadron of the British Grand Fleet early in 1918. Operating out of Scapa Flow and the Firth of Forth, TEXAS protected forces laying a North Sea mine barrage, responded to German High Seas Fleet sorties, fired at submarine periscopes observed by multiple ships and helped prevent enemy naval forces from interrupting the supply of Allied forces in Europe. Late in 1918 she escorted the German Fleet en route to its surrender anchorage and escorted President Wilson to peace talks in France. In 1919, she served as a plane guard and navigational reference for the first transatlantic flight by the seaplane NC-4, after which she transferred to the Pacific Fleet. Among other notables, she embarked President Coolidge for a trip to Cuba in 1928. In 1941 while on "Neutrality Patrol" in the Atlantic, TEXAS was stalked unsuccessfully by the German submarine U-203. TEXAS escorted Atlantic convoys against potential attack by German warships after America entered into WW II in December, 1941. In 1942, TEXAS transmitted General Eisenhower's first "Voice of Freedom" broadcast, asking the French not to oppose Allied landings on North Africa. The appeal went unheeded and the TEXAS provided gunfire support for the amphibious assault on Morocco, putting Walter Cronkite ashore to begin his career as a war correspondent. After further convoy duty, the TEXAS fired on Nazi defenses at Normandy on "D-Day," June 6, 1944. Shortly afterwards, she was hit twice in a duel with German coastal defense artillery near Cherbourg, suffering one fatality and 13 wounded. Quickly repaired, she shelled Nazi positions in Southern France before transferring to the Pacific where she lent gunfire support and antiaircraft fire to the landings on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. General Ship DataClass - New York Class Battleship Armament

Restoration of the TEXASPhoto courtesy of Margaret Hooper

Through the private donations and efforts of the people and businesses of the State of Texas, in addition to State funds, the ship underwent dry dock overhaul in 1988-90 and systematic restoration was begun. Instead of peacetime gray, the TEXAS was painted Measure 21 blue camouflage, which she wore during service in the Pacific in 1945. Nearly 350,000 pounds of steel plating were replaced that were previously removed by the Navy and structural repairs were made to the masts and superstructure of the ship. Following the removal of the non-historic layer of concrete on the main deck, work began on the installation of a new wooden decking. The work of saving the TEXAS in late 1980s has been a great source of pride throughout the state. The restoration would not have been possible if it had not been for the efforts of thousands of people including many school age children who "gave their pennies to save the TEXAS." While the ship officially reopened to the public on September 8, 1990, her restoration is not complete. During the last 10 years, many compartments and work areas on the ship have been carefully refurnished to portray life on a warship in 1945; however, plans have already begun for the next renovation of the TEXAS for the fall of 2005. While the search goes on for a suitable dry dock facility that will handle the weight and configuration of the battleship, the Texas legislature has already budgeted $12.5 million in funding for this renovation. Battleship Texas FoundationThe Battleship Texas Foundation (battleshiptexas.org) was created to assist ongoing preservation and educational efforts aboard this historic ship. Your membership in the Foundation helps ensure that the "Mighty T" continues to tell the story of those who fought for freedom on both sides of the globe. The Foundation engages in fundraising efforts to assist the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department with education, restoration, and maintenance efforts aboard the Battleship TEXAS. They also operate a Youth Education Program (Y.E.P.) to give youth group participants an opportunity to spend the night aboard ship and learn about Navy life in general.

|

In Processing. Pick ‘em up, put ‘em down.

Going aboard. The kids had to salute the OD, and permission to come aboard. Heh heh heh.

Spiderboy assists hoisting the pack colors from the yardarm.

Getting instructions on the proper way to toss our gear down the hatch.

Ready to tour.

The boys see their quarters

Wide open spaces. Note tables and benches stowed above.

The ship’s laundry.

Why is this called “the head” again?

The auxillary RADAR room, for the radio geeks.

Nothing like a spacious cabin for a restful night!

The pizza swiping varmit.

Hoisting the jack in the AM. Spiderboy had flag detail again.

The starboard side of turret #1. The ship has 5 turrets, each with twin 14” rifles.

The main bridge. The ship’s only cauaulty to enemy fire occurred on D-Day when a shell exploded below the bridge. A helmsman died a few hours late from his injuries.

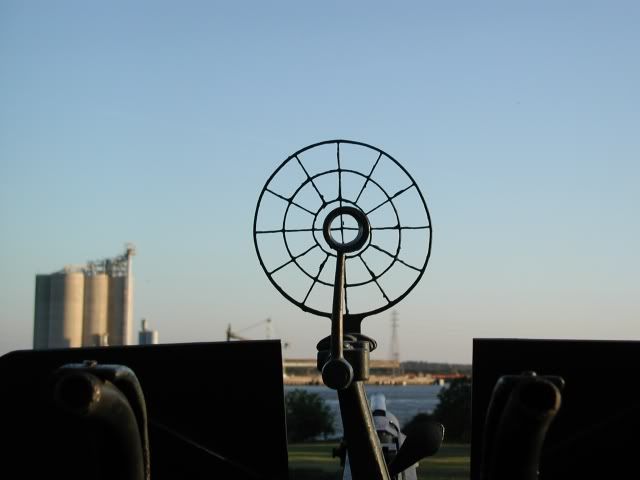

The helmsman’s view over the hood ornaments.

Ship’s bell, note the 1913 launch date.

Ship’s bell from the previous USS Texas.

Spiderboy mans the azimuth crank for a 3” gun.

Spiderboy graduates “Basic”. Dad did too BTW, and got labeled “old salt”.

The next day, the ladies came aboard. Bittygirl did not like the wind mussing her flaxen locks.

The San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site holds a significant responsibility to preserve the proud history of the State of Texas and the United States. The famous Battle of San Jacinto that brought TEXAS its independence was fought on this site. Because of the great importance of the Battle to the course of history, the Battleground is of state, national and international significance, a fact that is attested to by the site's National Historic Landmark status.

The primary purpose of the 1,200-acre site is to commemorate the Battle and to preserve the Battleground on which Texian troops under General Sam Houston achieved the independence of Texas by defeating a Mexican Army led by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna on April 21, 1836.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site consists of the Battleground, Monument and Battleship TEXAS. It is located within minutes of downtown Houston and a short distance to the beaches of Galveston Island. Millions of visitors come to this area each year to enjoy the mild coastal climate and cultural and sports activities. Students and visitors alike are most fortunate to be able to experience history first hand through living history at the San Jacinto Battleground and Battleship TEXAS State Historic Sites.

Hey, there’s a ship over there.

Spiderboy checks out the cornerstone.

Bittygirl and dad take a turn.

Yes, we were there at the same time.

My God, it’s full of stars seashells.

The history of Texas, Part I.

Part II.

Part III.

Part IV.

Part V.

Part VI. If’n ya’ can read through the washed out part.

Part VII.

Part VIII.

Even the stars are bigger in Texas!

Daddy, I’m scared.

Spiderboy’s turn to be scared.

Bittygirl checks out the Sea Wall through dad’s shoulder.

Hey, this isn’t so bad afterall.

Seagulls have chowed down on this jellyfish already.

We check out a jetty.

Sam Houston, one of the most illustrious political figures of Texas, was born on March 2, 1793, the fifth child (and fifth son) of Samuel and Elizabeth (Paxton) Houston, on their plantation in sight of Timber Ridge Church, Rockbridge County, Virginia.

He was of Scots-Irish ancestry and reared as a Presbyterian. He acquired rudimentary education during his boyhood by attending a local school for no more than six months.

When he was thirteen years old, his father died. Some months later, in the spring of 1807, he emigrated with his mother, five brothers, and three sisters to Blount County in Eastern Tennessee, where the family established a farm near Maryville on a tributary of Bakers’ Creek. Houston went to a nearby academy for a time and reportedly fed his fertile imagination by reading classical literature, especially the Iliad.

In 1859, two years before the start of the war between the states, he was opposed to having Texas secede from the union. In 1861, Texas voted to secede. Sam Houston refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new Confederacy and he was removed a governor.

He retired to Huntsville, Texas. He chose this city because the hills reminded him of his boyhood home near Maryville, Tennessee. He was seventy years old at the time of his death on July 26th, 1863. He died in Huntsville, TX at 6:15 p.m.

Soldier, statesman and rollicking character, Sam Houston walked across history.

Spiderboy and Bittygirl check out the big dude.

Whoa!

Bittygirl says, “wait up daddy.”

Checking the names on the fund raising bricks.

Some guy from Poland.

Some guy from Houston.

Some guy from Austin.

Lovely, absolutely lovely.

Hi miss Feather.

The word for the day is:

Duck

Translation:

Stuck

Usage:

Daddy, gimme out of this car seat PLEASE!

I'll throw in the full DANFS entry:

Texas

After having been a territory first of Spain and then of Mexico and later an independent republic, Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on 29 December 1845.

II

(Battleship No. 35: displacement 27,000 tons; 1ength 573'0"; beam 95'2½" (water line); draft 29'7"; speed 21.05 knots (trial); complement 954; armament 10 14-inch guns, 21 5-inch guns, 4 3-pounders, 4 21-inch torpedo tubes (submerged); class New York)

The second Texas (Battleship No. 35) was laid down on 17 April 1911 at Newport News, Va., by the Newport News Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 18 May 1912; sponsored by Miss Claudia Lyon; and commissioned on 12 March 1914, Capt. Albert W. Grant in command.

On 24 March, Texas departed the Norfolk Navy Yard and, after a stop at Hampton Roads, set a course for New York. She made an overnight stop at Tompkinsville, N.Y., on the night of the 26th and 27th and entered the New York Navy Yard on the latter day. She spent the next three weeks there undergoing the installation of the fire control equipment.

During her stay in New York, President Woodrow Wilson ordered a number of ships of the Atlantic Fleet to Mexican waters in response to tension created when an overzealous detail of Mexican Federal troops detained an American boat crew at Tampico. The problem was quickly resolved locally, but fiery Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo sought further redress by demanding an official disavowal of the act by the Huerta regime and a 21-gun salute to the American flag.

Unfortunately for Mexican-American relations, President Wilson apparently saw in the incident an opportunity to put pressure on a government he felt was undemocratic. On 20 April, Wilson placed the matter before the Congress and sent orders to Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, commanding the naval force off the Mexican coast, instructing him to land a force at Veracruz and to seize the customs house there in retaliation for the celebrated "Tampico Incident." That action was carried out on the 21st and 22d.

Due to the intensity of the situation, when Texas put to sea on 13 May, she headed directly to operational duty without benefit of the usual shakedown cruise and post-shakedown repair period. After a five-day stop at Hampton Roads between 14 and 19 May, she joined Rear Admiral Fletcher's force off Veracruz on the 26th. She remained in Mexican waters for just over two months, supporting the American forces ashore. On 8 August, she left Veracruz and set a course for Nipe Bay, Cuba, and thence steamed to New York where she entered the Navy Yard on 21 August.

The battleship remained there until 5 September when she returned to sea, joined the Atlantic Fleet, and settled into a schedule of normal fleet operations. In October, she returned to the Mexican coast. Later that month, Texas became station ship at Tuxpan, a duty that lasted until early November. The ship finally bade Mexico farewell at Tampico on 20 December and set a course for New York. The battleship entered the New York Navy Yard on 28 December and remained there undergoing repairs until 16 February 1915.

Upon her return to active duty with the fleet, Texas resumed a schedule of training operations along the New England coast and off the Virginia Capes alternated with winter fleet tactical and gunnery drills in the West Indies. That routine lasted just over two years until the February-to-March crisis over unrestricted submarine warfare catapulated the United States into war with the Central Powers in April 1917.

The 6 April declaration of war found Texas riding at anchor in the mouth of the York River with the other Atlantic Fleet battleships. She remained in the Virginia Capes-Hampton Roads vicinity until mid-August conducting exercises and training naval armed-guard gun crews for service on board merchant ships.

In August, she steamed to New York for repairs, arriving at Base 10 on the 19th and entering the New York Navy Yard soon thereafter. She completed repairs on 26 September and got underway for Port Jefferson that same day. During the mid-watch on the 27th, however, she ran hard aground on Block Island. For three days, her crew lightened ship to no avail. On the 30th, tugs came to her assistance, and she finally backed clear. Hull damaged dictated a return to the yard, and the extensive repairs she required precluded her departure with Division 9 for the British Isles in November.

By December, she had completed repairs and moved south to conduct war games out of the York River. Mid-January 1918 found the battleship back at New York preparing for the voyage across the Atlantic. She departed New York on 30 January; arrived at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland on 11 February; and rejoined Division 9, by then known as the 6th Battle Squadron of Britain's Grand Fleet.

Texas' service with the Grand Fleet consisted entirely of convoy missions and occasional forays to reinforce the British squadron on blockade duty in the North Sea whenever German heavy units threatened. The fleet alternated between bases at Scapa Flow and at the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Texas began her mission only five days after her arrival at Scapa Flow where she sortied with the entire fleet to reinforce the 4th Battle Squadron, then on duty in the North Sea. She returned to Scapa Flow the next day and remained until 8 March when she put to sea on a convoy escort mission from which she returned on the 13th. Texas and her division mates entered the Firth of Forth on 12 April but got underway again on the 17th to escort a convoy. The American battleships returned to base on 20 April. Four days later, Texas again stood out to sea to support the 2d Battle Squadron the day after the German High Seas Fleet had sortied from Jade Bay toward the Norwegian coast to threaten an Allied convoy. Forward units caught sight of the retiring Germans on the 25th but at such extreme range that no possibility of bringing the enemy to battle existed. The Germans returned to their base that day, and the Grand Fleet, including Texas, did likewise on the next.

Texas and her division mates passed a relatively quiescent May in the Firth of Forth. On 9 June, she got underway with the other warships of the 6th Battle Squadron and headed back to the anchorage at Scapa Flow, arriving there the following day. Between 30 June and 2 July, Texas and her colleagues acted as escort for American minelayers adding to the North Sea mine barrage. After a two-day return to Scapa Flow, Texas put to sea with the Grand Fleet to conduct two days of tactical exercises and war games. At the conclusion of those drills on 8 July, the fleet entered the Firth of Forth. For the remainder of World War I, Texas and the other battleships of Division 9 continued to operate with the Grand Fleet as the 6th Battle Squadron. With the German Fleet increasingly more tied to its bases in the estuaries of the Jade and Ems Rivers, the American and British ships settled more and more into a routine schedule of operations with little or no hint of combat operations. That state of affairs lasted until the armistice ended hostilities on 11 November 1918. On the night of 20 and 21 November, she accompanied the Grand Fleet to meet the surrendering German Fleet.

The two fleets rendezvoused about 40 miles east of May Island—located near the mouth of the Firth of Forth—and proceeded together into the anchorage there. Afterward, the American contingent moved to Portland, England, arriving there on 4 December.

Eight days later, Texas put to sea with Divisions 9 and 6 to meet President Woodrow Wilson embarked in George Washington on his way to the Paris Peace Conference. The rendezvous took place at about 0730 the following morning and provided an escort for the President into Brest, France, where the ships arrived at 1230 that afternoon. That evening, Texas and the other American battleships departed Brest for to return to the United States. The warships arrived off Ambrose Light on Christmas Day 1918 and entered New York on the 26th.

Following overhaul, Texas resumed duty with the Atlantic Fleet early in 1919. On 9 March, while lying at anchor in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, she became the first American battleship to launch an airplane when Lt. Comdr. Edward O. McDonnell flew a British-built Sopwith "Camel" off the warships' No. 2 turret. That summer, she was reassigned to the Pacific Fleet. On 17 July 1920, she was designated BB-35 as a result of the Navy's adoption of the alpha-numeric system of hull designations. Texas served in the Pacific until 1924 when she returned to the east coast for overhaul and to participate in a training cruise to European waters with Naval Academy midshipmen embarked. She entered the Norfolk Navy Yard on 31 July 1925 for a major modernization overhaul during which her cage masts were replaced with a single tripod foremast. She also received the very latest in fire control equipment. Following that overhaul, she resumed duty along the eastern seaboard and kept at that task until late in 1927 when she did a brief tour of duty in the Pacific between late September and early December.

Near the end of the year, Texas returned to the Atlantic where she served as flagship of the United States Fleet . In January 1928, she transported President Calvin Coolidge to Havana for the Pan-American conference and then continued on via the Panama Canal and the west coast to maneuvers with the fleet near Hawaii.

She returned to New York early in 1929 for her annual overhaul and had completed it by March when she began another brief tour of duty in the Pacific. She returned to the Atlantic in June and resumed normal duty with the Scouting Fleet. In April 1930, she took time from her operating schedule to escort SS Leviathan into New York when that ship returned from Europe carrying the delegation that had represented the United States at the London Naval Conference. In January 1931, she left the yard at New York as flagship of the United States Fleet and headed via the Panama Canal to San Diego, her home port for the next six years. During that period, she served first as flagship for the entire Fleet and, later, as flagship for Battleship Division (BatDiv) 1.

In the summer of 1937, she once more was reassigned to the east coast, as the flagship of the Training Detachment, United States Fleet. Late in 1938 or early in 1939, the warship became flagship of the newly organized Atlantic Squadron, built around BatDiv 5. Through both organizational assignments, her labors were directed primarily to training missions, midshipman cruises, naval reserve drills, and training members of the Fleet Marine Force. These missions became more urgent following the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939.

In May 1941, Texas began operating on the "neutrality patrol," established to keep the war out of the western hemisphere, though these cruises were mainly along the east coast and occassionally into the West Indies. Sunday, 7 December 1941, found the battleship at Casco Bay, Maine, undergoing a rest and relaxation period following three months of watch duty at Argentia, Newfoundland. After 10 days of Casco Bay, she returned to Argentia and remained there for the holidays. In late January 1942 she got underway to escort a convoy to British waters before proceeding to Iceland to watch out for German surface raiders. Returning home in March, the battleship resumed convoy-escort missions. On one occasion, she escorted Guadalcanal-bound marines as far as Panama. On another, the warship screened service troops to Freetown, Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa. More frequently, she made voyages to and from Great Britain escorting both cargo- and troop-carrying ships.

On 23 October, Texas embarked upon her first major combat operation when she sortied with Task Group (TG) 34.8, the Northern Attack Group for Operation "Torch," the invasion of North Africa. The objective assigned to this group was Mehedia near Port Lyautey and the port itself. The ships arrived off the assault beaches early in the morning of 8 November and began preparations for the invasion. When the troops went ashore, Texas did not come immediately into action to support them. At that point in the war, amphibious warfare doctrine was still embryonic; and many did not recognize the value of a prelanding bombardment. Instead, the Army insisted upon attempting surprise. Texas finally entered the fray early in the afternoon when the Army requested her to destroy an ammunition dump near Port Lyautey. For the next week, she contented herself with cruising up and down the Moroccan coast delivering similar, specific, call-fire missions. Thus, unlike in later operations, she expended only 273 rounds of 14-inch and 6 rounds of 5-inch. During her short stay, some of her crew briefly went ashore to assist in salvaging some of the shipping sunk in the harbor. On 15 November, she departed North Africa and headed for home in company with Savannah (CL-42), Sangamon (ACV-26), Kennebec (AO-36), four transports, and seven destroyers.

Throughout 1943, Texas carried out the familiar role of convoy escort. With New York as her home port, she made numerous transatlantic voyages to such places as Casablanca and Gibraltar, as well as frequent visits to ports in the British Isles. That routine continued into 1944 but ended in April of that year when, at the European end of one such mission, she remained at the Clyde estuary in Scotland and began training for the invasion of Normandy. That warm-up period lasted about seven weeks at the end of which she departed Belfast Lough and travelled down the Irish Sea and around the southern coast of England to arrive off the Normandy beaches on the night of 5 and 6 June.

At about 0440 on the morning of the 6th, the battleship closed the Normandy coast to a point some 12,000 yards offshore near Pointe du Hoc. At 0550, Texas began churning up the coastal landscape with her 14-inch salvoes. Meanwhile, her secondary battery went to work on another target on the western end of "Omaha" beach, a ravine laced with strong points to defend an exit road. Later, under control of airborne spotters, she moved her major-caliber fire inland to interdict enemy reinforcement activities and to destroy batteries and other strong points farther inland.

By noon, she closed the beach to about a range of 3,000 yards to fire upon snipers and machinegun nests hidden in a defile just off the beach. At the conclusion of that mission, the warship took an enemy antiaircraft battery located west of Vierville under fire.

The following morning, her main battery rained 14-inch shells on the enemy-held town of Trevieres to break up German troop concentrations. That evening, she bombarded a German mortar battery which had been shelling the beach. Not long after midnight, German planes attacked the ships offshore, and one of them swooped in low on Texas' starboard quarter. Her antiaircraft batteries opened up immediately but failed to score on the intruder. On the morning of 8 June, her guns fired on Isigny, then on a shore battery, and finally on Trevieres once more.

After that, she retired to Plymouth to rearm, returning to the French coast on the llth. From then until the 15th, she supported the Army in its advance inland. However, by the latter day, the troops had advanced beyond the range of her guns; and the battleship moved on to another mission.

On the morning of 25 June, Texas closed in on the vital port of Cherbourg and, with Arkansas (BB-33), opened fire upon various fortifications and batteries surrounding the town. The guns on shore returned fire immediately and, at about 1230, succeeded in straddling Texas. The battleship, however, continued her firing runs in spite of shell geysers blossoming about her. The enemy gunners were stubborn and good. At 1316 a 280-millimeter shell slammed into her fire control tower, killed the helmsman, and wounded nearly everyone on the navigation bridge. Texas' commanding officer, Capt. Baker, miraculously escaped unhurt and quickly had the bridge cleared. The warship herself continued to deliver her 14-inch shells in spite of damage and casualties. Some time later, another shell struck the battleship. That one, a 240-millimeter armor-piercing shell, crashed through the port bow, entered a compartment located below the wardroom, but failed to explode. Throughout the three-hour duel, the Germans straddled and near-missed Texas over 65 times, but she continued her mission until 1500 when, upon orders to that effect, she retired.

Texas underwent repairs at Plymouth, England, and then drilled in preparation for the invasion of southern France. On 15 July, she departed Belfast Lough and headed for the Mediterranean. After stops at Gibraltar and Oran in Algeria, the battleship sailed to Taranto, Italy, before setting a course for the Riviera coast of France. She arrived off St. Tropez during the night of 14 and 15 July. At 0444, she moved into position for the prelanding bombardment and, at 0651, opened up on her first target, a battery of five 155-millimeter guns. Due to the fact that the troops ashore moved inland rapidly against light resistance, she provided fire support for the assault for only the first day. Texas departed the southern coast of France on the evening of 16 August. After a stop at Palermo, Sicily, she left the Mediterranean and headed for New York where she arrived on 14 September 1944.

At New York, Texas underwent a month-ling repair period during which the barrels on her main battery were replaced. After a brief refresher cruise to Casco Bay, she departed Maine in November and set a course, via the Panama Canal, for the Pacific. She made a stop at Long Beach, Calif., and then continued on to Oahu. She spent Christmas at Pearl Harbor and then conducted maneuvers in the Hawaiian Islands for two weeks before steaming to Ulithi Atoll. She departed Ulithi on 10 February 1945, stopped in the Marianas for two days' invasion rehearsals, and then set a course for Iwo Jima. She arrived off the target on 16 February, three days before the scheduled assault. She spent those three days pounding enemy defenses on Iwo Jima in preparation for the landings. After the troops stormed ashore on the 19th, Texas switched roles and began delivering support and call fire. She remained off Iwo Jima for almost a fortnight, helping the marines subdue a well dug-in and stubborn Japanese garrison.

Texas cleared Iwo Jima on 7 March and returned to Ulithi to prepare for the Okinawa operation. She departed Ulithi with TF 54, the gunfire support unit, on 21 March and arrived in the Ryukyus on the 25th. Texas did not participate in the occupation of the islands and roadstead at Kerama Retto carried out on the 26th but moved in on the main objective instead, beginning the prelanding bombardment that same day. For the next six days, she delivered 14-inch salvoes to prepare the way for the Army and the Marine Corps. Each evening, she retired from her bombardment position close to the Okinawan shore only to return the next day and resume her poundings. The enemy ashore, preparing for a defense-in-depth strategy as at Iwo Jima, made no answer. Only his air units provided a response, sending several kamikaze raids to harass the bombardment group. Texas escaped damage during those small attacks. After six days of aerial and naval bombardment, the ground troops' turn came on 1 April. They stormed ashore against initially light resistance. For almost two months, Texas remained in Okinawan waters providing gunfire support for the troops ashore and fending off the enemy aerial assault. In performing the latter mission, she claimed one kamikaze kill on her own and three assists.

On 14 May Texas retired to Leyte in the Philippines and remained there until after the Japanese capitulation on 15 August. She returned to Okinawa toward the end of August and stayed in the Ryukyus until 23 September. On that day, she set a course for the United States with troops embarked. The battleship delivered her passengers to San Pedro, Calif., on 15 October. She celebrated Navy Day there on 27 October and then resumed her mission bringing American troops home. She made two round-trip voyages between California and Oahu in November and a third in late December.

On 21 January 1946, the warship departed San Pedro 117 and steamed via the Panama Canal to Norfolk where she arrived on 13 February. She soon began preparations for inactivation. In June, she was moved to Baltimore, Md., where she remained until the beginning of 1948. Texas was towed to San Jacinto State Park in Texas where she was decommissioned on 21 April 1948 and turned over to the state of Texas to serve as a permanent memorial. Her name was struck from the Navy list on 30 April 1948.

Texas (BB-35) earned five battle stars during World War II.

|

|

Texas (BB-35) about 1930, as flagship of the United States Fleet. (80-G-1021418)

Lookee 'ere Y'all

Great pics and really nice tour! Nice timing for posting, too. Thanks for sharing.

Folks, a reminder for those who use Windows. Today is Patch Tuesday. Be sure to download those updates.

| April 11, 2006

The Glorious Sunset

Read:

|

It is wonderful to be young, with clear sight, acute hearing, elastic step, pulses drumming to the march of exhilarating health. But old age has glories that youth cannot know. It is a blessed old age indeed if it ends brightly at evening time.

It is wonderful to be young, with clear sight, acute hearing, elastic step, pulses drumming to the march of exhilarating health. But old age has glories that youth cannot know. It is a blessed old age indeed if it ends brightly at evening time.

Old age celebrates the harvest—youth the sowing. Like fruit in the fall, the harvest of old age will either dry up and wither, or grow mellow and sweeter as it ripens.

You cannot escape the advancing years. Youth stays long enough only to strengthen our shoulders for the burdens ahead. Life leads inevitably to the evening time. But the best things are the oldest things—things that have endured and stood the test of time. God Himself—though not bound by time—is called the Ancient of Days (Daniel 7:9).

So don't be ashamed to own your age. Everything that abides must become old: mountains, rivers, oceans, stars.

But the evening time of life can be bright only if we have the One who is the Light as our evening Sun. Nothing is sadder than an aging person facing eternity without Jesus. And nothing is sweeter than a gently mellowing Christian, still growing and resting in Christ as he faces God's tomorrow with confidence. —M. R. De Haan, M.D.

It is a strange thing that, while all would live long, none would be old. —Benjamin Franklin

Wow. I remember seeing all that when I was about 10 years old. Thanks for the great thread and all the memories.

I don't get credit it for this one, P.E. and gang get the hat tip.

Have a great day

Regards

alfa6 ;>}

The Top Ten Facts About The Construction of THE SAN JACINTO MONUMENT

by Johnny Stucco

San Jacinto Monument

Aerial View of the San Jacinto Monument

Photo Courtesy Captain Robert L. Sadler, Jr.

The San Jacinto Monument was designed by the prolific Houston architect Alfred Finn to commemorate the Centennial of the Battle of San Jacinto.

There is no particular order of importance to the entries - numbers are provided to save the reader the trouble of counting.

1. Despite what your uncle told you, no one was buried alive in wet concrete.

2. Only 35 of the 150 men hired had construction experience.

3. After completion, the mast and boom were removed by lowering them through the elevator shaft since the taper of the monument wouldn't allow lowering.

4. The shaft rose at the rate of 24 feet per week.

5. The working platform (which rose as the shaft was built) weighted 65 tons.

6. The star on the top weighs 220 tons.

7. The 3 dimensional star is 34 feet from point to point.

8. The sculpted stone panels immediately above the museum weigh 4 tons each.

9. The re-enforcement bars were 2 inches by 2 inches and 110 feet long.

10. The bars were easily bent, but were straightened by a railroad rail-straightening device that the contractor borrowed from a local railroad yard.

San jacinto Monument aerial view

Aerial View of the San Jacinto Monument

Photo Courtesy Captain Robert L. Sadler, Jr.

BONUS FACT: (Bring this up quietly when you visit Washington D.C.) The San Jacinto Monument IS taller than the Washington Monument.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.