|

Posted on 04/03/2003 5:33:15 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. We hope to provide an ongoing source of information about issues and problems that are specific to Veterans and resources that are available to Veterans and their families. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support.

|

|

|

|

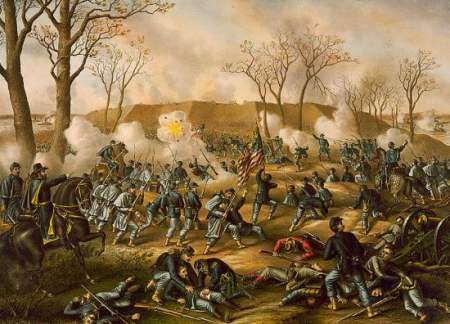

The fall of Forts Henry & Donelson in February 1862 launched U.S. Grant's Mississippi campaign culminating in the capture of Vicksburg. The forts were located near Dover, TN in what is now called "The Land Between the Lakes" -- which was actually the land between the rivers -- about an hour's drive northwest of Nashville.  In looking at the pre-battle chatter, it seems that no one really understood the importance of Forts Henry & Donelson. The beloved Albert Sidney Johnston had a 500-mile front to defend -- from Island No. 10 north of Memphis to the Cumberland Gap. For him, everything was strategic since any loss would open up an invasion route. On the Union side, the Henry & Donelson issue was more happenstance than anything else. Lew Wallace writes post-war that the origins of the idea are obscure, but we are sure that Grant pushed the plan on his boss Halleck. However, Grant was more interested in alleviating his boredom than any brilliant strategic move. Halleck was the true bureaucrat: avoid blame no matter what. He put off Grant until it looked like he would be upstaged by Buell after Mill Springs. What they all missed were the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers. Losing the Cumberland Gap left a Union army to forage in Eastern Tennessee. After Island No. 10 were Memphis and Vicksburg -- major defensive points. When Henry & Donelson fell the next stop was Muscle Shoals, Alabama.  To illustrate, note that after Grant passed Henry & Donelson his next fight was at Pittsburg Landing just north of Corinth, MS. Nashville and Clarksville, with its important ironworks, were exposed to Foote's gunboats and quickly surrendered. Memphis and Vicksburg now had to look to an attack from the east as well at upriver. It was an accidentally brilliant strategic move, devastating to the Confederacy. Fort Henry fell quickly to the gunboats, so the main battle interest is at Fort Donelson. The winter march was something of a novelty in 1862. It shows how the military thinking was stuck in the Napoleonic Era when the wet weather would foul the gunpowder used to prime the pan. Fort Henry was clearly untenable, in a low area on the east side of the Tennessee. A. S. Johnston had repeatedly ordered that the high ground on the west side of the River be fortified. There was a Fort Heiman already in place on the west side, but it was in "neutral" Kentucky. No other action was taken. By February 1862, Fort Henry was partially inundated and the river threatened to flood the rest. It was a typical earthen fort with outdated guns and a smallish garrison. On February 4-5, Grant landed his divisions after reconnoitering at two locations, one on the east bank of the Tennessee River to prevent the garrison’s escape and the other to occupy the high ground on the west side which would insure the fort’s fall. The only tactical obstacle on the east side was a small stream, but to land the forces any closer would have put them in gun range from the fort. Flag-Officer Andrew H. Foote’s seven gunboats closed within 400 yards and began bombarding the fort.  Lloyd Tilghman, commander of the fort’s garrison, realized that it was only a matter of time before Fort Henry fell. While leaving artillery in the fort to hold off the Union fleet, he escorted the rest of his force out of the area and sent them safely off on the route to Fort Donelson, 10 miles east. Tilghman then returned to the fort and surrendered to the fleet. Fort Henry’s also let Grant send the gunboats upriver to destroy some critical railroad bridges. From February 6 to 16, the missing man in the equation was Albert Sidney Johnston, Confederate commander in the west. On February 7, the day after Fort Henry fell, he held a staff meeting at his headquarters in Bowling Green where he decided to split his forces, sending 12,000 reinforcements to Fort Donelson and falling back from Bowling Green to Nashville with the remainder. The strategic issue here was to prevent Grant and Buell's army in Kentucky from uniting. Grant was the weaker of the two forces, and his supply line from Fort Henry traveled back 150 miles to Halleck's command in St. Louis. An immediate attack against Grant would also have the advantage of the Fort Donelson garrison. From February 6th to the 16th, Grant was stuck in the mud.  Johnston was able to quickly assemble troops for an attack at Shiloh, but for some reason he was unwilling to react to the loss of Henry. Even then, it seems that no one really understood just how far the rivers reached. After capturing Fort Henry on February 6, Grant advanced cross-country to invest Fort Donelson. He was opposed by Confederate commander John Floyd, who made no attempt to oppose Grant's advance. By February 14 Grant had a loose half-circle around the fort. On February 14 Foote's gunboats tried another bombardment. However, the guns at Donelson were newer and better sited, and Foote took serious loses and retreated downriver. The Union ground forces tested the earthworks, which had been thrown up mostly after the fall of Henry. Floyd determined to break out, and his attack on February 15 actually opened up a corridor. Grant launched an inconclusive counterattack which so unnerved Floyd that he ordered the troops back into the fort and started making plans to surrender. Nathan Bedford Forrest said that he didn't join the Confederacy to surrender his command and took his cavalry out across the Cumberland River.  Johnston had designated the forts as "strategic." Even in Confederate parlance, this meant something more vigorous than a quick surrender. The fall of the two forts and the loss of 13,000 Southern troops was a major victory for Grant and a catastrophe for the South. Shortly afterwards Johnston abandoned Nashville, which was ostensibly the reason why he hadn't attacked Grant in the first place. The loss ensured that Kentucky would stay in the Union and opened up Tennessee for an advance along the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. Along with the fall of New Orleans it also demonstrated that the idea of and "independent nation" was a sham. The Union army could now go wherever it wanted. Confederate scouts searched for avenues of escape that night. Army doctors counseled that the men could not survive crossing frozen creeks and the long trek to Nashville. Buckner became gripped by battle fatigue and fears of Smith's division. Pillow urged continued resistance, Floyd vacillated. Time was wasted and in a midnight council that has since been defined understanding, a decision was made to surrender to Grant on the morrow. Forrest stalked angrily into the night, vowing to escape. Floyd and Pillow, fearing punishment at the hands of Union authorities, similarly deserted, passing command to Buckner. Floyd's three thousand man Virginia brigade, Pillows personal staff and uncounted hundreds of others evaded the Union dragnet over the days after the surrender. But when Buckner sent a flag of truce to his opponent that night, the Confederate fighting men became enraged and nearly mutinied at this betrayal by their leaders. Eventually, Buckner met with his old army friend, Grant in the hamlet of Dover, within Confederate lines. Grant demanded unconditional surrender and Buckner, though aghast at such treatment from an old colleague was powerless to refuse. Grant telegraphed Halleck later that day. "We have taken Fort Donelson and from 12,000 to 15,000 prisoners including Generals Buckner and Bushrod Johnson, also about 20,000 stands of arms, 48 pieces of artillery, 17 heavy guns, from 2,000 to 4,000 horses and large quantities of commissary stores."  When this news reached Johnston at Nashville, he was shocked, since all previous news from the fort indicated victory. Nashvillians rioted and fled the city in droves with Buell's army eventually occupying the capital on February 24. Johnston could provide no defense. Aided by Floyd, Pillow and Forrest, his forces evacuated as much Confederate property as possible but his retreat did not stop short of Northern Alabama and Mississippi. Union forces stood poised to end the rebellion all over the upper South. But, as fatigued and battered in victory as the Confederates were in defeat, Grant's men could not move quickly. Moreover, their generals fell to bickering and momentum slipped from their grasp. Johnston was able to regroup to fight another day. Still, a Confederate field force was swept into Northern prison camps. Western and much of middle Tennessee as well as all of Kentucky were reclaimed for the Union. Hopes of early European recognition of the Confederacy were dashed. Johnston's reputation as the South's greatest warrior was destroyed. The fall of Forts Henry and Donelson changed the war in the West overnight. Flagging spirits in the North were revived, and a deep wedge was driven into the South. The Southern home front began its wavering trend toward eventual collapse in a war of attrition.

|

How are you? So good to see you.

I miss you too.

This "manly and humane policy" is being prosecuted in Iraq with telling result.

Photo taken at about age 70, when this manuscript was written. He died at the age of 74 and is buried near Rose Hill, Mississippi. His father, Rev. George Washington Ryan (1811-1898), recruited and was Captain of Co. G, 8th MS Regiment (Tolson Guard), CSA.

EXPERIENCE OF A CONFEDERATE SOLDIER IN CAMP AND PRISON IN THE CIVIL WAR 1861-1865

I left my home (near Rose Hill, Jasper County, MS) and loved ones with three other companions on the second day of June, 1861 and went to Corinth, Mississippi where the Miss. Troops were rendezvoused and being drilled for the conflict. I was so afraid that the Yankees would be whipped before I could get there. I would not wait for a company to be formed at home. After looking around a day or two we decided to join the Enterprise Guard, which was designated Company B., and was one of ten companies composing the Fourteenth Mississippi Regiment. I was small for my age, not weighing over a hundred pounds, and tender looking, with not a sign of beard on my face.

R.S. Weir was Captain of Company B, when I made application to join his company. He looked at me as though he doubted the propriety of receiving me. He doubtless would have rejected me had it not been for my companions who were with me and older than I. They testified that my parents were willing for me to join the army. However, it was not long before he found that I was made of good tough stuff. I was often detailed to perform some difficult task because I did not give out as some did who were much stouter than I. I suppose we remained at Corinth for two or three months drilling every day. Finally to our great joy we received orders to go to Russellville in East Tennessee. The Union men and Southern sympathizers were having a hot time. The Southern sympathizers were in the minority and were being terribly persecuted by the Union men. We soon restored order and gave all who wanted to join the Confederate Army a chance to do so. We were next ordered to Bowling Green, Kentucky, where we thought we were going into winter quarters. Some time in January 1862 we were ordered to Russellville, Ky. We remained there a short time and were ordered to Fort Donelson. On arrival we were ordered in the breast works surrounding the fort.

I will describe the battle of Fort Donelson [-1-], more minutely than any other in which I was engaged from the fact that it was my first Baptism of Shot and Shell and was a land and naval battle all in one. Fort Donelson consisted of two batteries on the Cumberland River, protected by breast works surrounding it. On the 12th day of February, 1862, The battle opened with sharp shooting all along the line on both sides. The first day’s battle closed with no perceptible gain by either side. Day broke on the 13th to wind two armies looking each other in the face. The cannonading and sharp shooting commenced as the day before had. The Yankees brought up one gun boat near the fort and fired about one hundred and fifty shots. The one of our 128 lb. Balls went crashing through her, damaging her so she went drifting out of sight and was seen no more. Along the fortifications the Infantry kept a continual firing on both sides all day, killing and wounding a great many on both sides. The dead and wounded were left on the battle field to take a terrible snow storm which fell that night several inches deep. Some of the wounded scratched around to save their lives from the burning woods that had caught on fire from the guns during the day’s battle (which was a beautiful fair day) and remained there to perish in the snow.

Day broke on the 14th to find everything covered in snow. We were without shelter, food, or fire to warm by, except for a few small sticks. Up until this time we scored victory at every point. The enemy attacked our works at every point and were repulsed with heavy loss. While we were rejoicing over victories they were greatly reinforced. At the break of day on the 15th we were far outside the lines of our breast works, attacking; firing volley after volley into them as they huddled by their camp fires. Having taken them by surprise, with less than 8,000 men we waded through the snow and routed 30,000; capturing over 5,000 stands of small arms, six pieces of artillery, and a great many prisoners. Twice that day the 14th Miss. Reg. To which I belonged was ordered to a bayonet charge, but the Yankees would not stand. Gen. Buckner had opened the way for our escape, but instead of that he was ordered by our chief commanders, Floyd and Pillow, back to the trenches we had left the day before.

General Grant had been receiving reinforcements every day, until now his forces numbered over four to one of our worn-out, frozen soldiers. During the night of the 15th a council of war was held. The same was communicated to General Grant, who proposed surrender. General Forest was in the council and refused to surrender. He contended that the way was open for us to march out and he marched his command (which was Cavalry) all along our lines of works. This was the first intimation we had that we were prisoners of war. So we had nothing to do but stand around our fires and talk of our experiences and narrow escapes during the four days of carnage.

Chapter II

The next morning after our surrender we were marched to the river where there were several old hulks of steam boats that appeared to be rotted from bottom to top. We were crowded on the lower decks one thousand to the boat. We were much more in danger on the decks of these old boats that we were when we were facing Yankee bullets. We had no idea where we were going. We were carried to Cairo, Illinois; the up the Mississippi by way of St. Louis to Alton, Ill. We were landed there after spending eight days on the lower decks of those old boats, eating and sleeping on stone coal scattered all over the bottom almost knee deep. We were crowded into cattle cars like so many cattle and horses and after twelve hours ride, through a terrible blizzard, we were landed at Chicago, a motley looking set. We had all our cooking utensils with us, camp kettles, skillets, ovens, frying pans, coffee pots, tin pans, tin cups, and plates. We had them on our heads, on our backs, swinging from our sides, and in our hands. Some of our boys were bareheaded, having their hats blown off on the way; some had hats and caps with no brims, and some with no crowns. As we were the first batch of prisoners we were quite a show. The people had to see us so we were marched out in square to square and from street to street with thousands of people running over each other to see us. Some would curse us and call us poor, ignorant devils; some would curse Jeff Davis for getting us ‘poor ignorant creatures’ into such a trap. I suppose the children had been told that we had horns and tails, for they crowded near us and kept saying, “where are their horns and where are their tails, I don’t see them.”

After we were almost frozen we were marched two miles to Camp Douglas Prison. Every step of the way was through ice cold mud. Our pants legs up to our knees were frozen as stiff as raw hides. The people by the hundreds followed us to the very gates of the prison, and from that day on it seemed that they never tired of looking at us. The visited the prison everyday in great crowds until an order was issued prohibiting it. The some enterprising Yankee built an observatory just outside the prison wall. It was crowded with people from morning until night. Camp Douglas had been erected for a rendezvous and drilling ground for Ill. Troops. Every thing looked new and clean. I think that we were the first arrival of prisoners. Each barracks had a capacity of 125 prisoners. On each side of the barracks there were three tiers of bunks, one above another, with a narrow hall between and a heater in the center. The prison was laid off in squares and had the appearance of a little town. It had a plank wall around it 15 ft. high with a 3 ft. walk on top for the guards to walk on. There was a commissary in the center where our rations were kept and issued every morning. They fed us very well on provisions they would not issue their own soldiers.

The guards, or Hospital Rats, as we called them, had never been to the front and seen any service and they were overbearing and cruel in the extreme. We had some boys who would not take anything from them. We all got water from Lake Michigan by Hydrant, the guards as well as prisoners. At first when they came for water and found one of our buckets under the pump they would kick it over and place theirs in its place. They never failed to get knocked down when they did this and before they could recover the one who had done it would be hidden in some barracks and we would never give each other away. However, they were not long in learning that it was a risky business.

Sometimes our boys, for some trivial offense, would be punished by putting them in the white oak, as they called it. It was a guard house made of white oak logs twelve or fourteen inches in diameter, notched down close with one small window in the end. Inside, the wall was a dungeon eight or ten feet deep. It was entered by a trap door, a pair of steps led down into this dark foul hole. It was pitch dark in there; one could not see his hand before him when the door was closed. One who had not been is such a place cannot have the least conception of it. I was thrown in this place for a trivial offense, for attempting to get a bucket of water at a hospital well while our hydrant was out of fix. I spent four of the most wretched hours of my life in that terrible place. I was taken out by the same guard who put me in there, and the cursing he gave me when he let me out would be a sin for me to repeat. I opened not my mouth; I knew better. I received one more genteel cursing while wounded in the prisoner’s hospital at Nashville, which I will speak of later on. There were some of our poor boys, for little infraction of the prison rules, riding what they called Morgan’s mule every day. That was one mule that did the worst standing stock still. He was built after the pattern of those used by carpenters. He was about fifteen feet high; the legs were nailed to the scantling so one of the sharp edges was turned up, which made it very painful and uncomfortable to the poor fellow especially when he had to be ridden bareback, sometimes with heavy weights fastened to his feet and sometimes with a large beef bone in each hand. This performance was carried on under the eyes of a guard with a loaded gun, and was kept up for several days; each ride lasting two hours each day unless the fellow fainted and fell off from pain and exhaustion. Very few were able to walk after this hellish Yankee torture but had to be supported to their barracks. There was another diabolical device invented; that was the ball and chain route. However that was seldom used unless some of the prisoners attempted to escape and were caught. The chain was riveted around the ankle and the ball at the other end of the chain. It was almost as much as the poor fellow could carry. That was one thing that stuck closer than a brother. It went with him by day and by night, and even lay by his side in his cold naked bunk at night.

Sometime in September after our capture in February we, to our unspeakable joy received notice that we would soon be exchanged and sent back to dear ol Mississippi. We were this time marched to the railroad and packed in horse and cattle cars which were filthy in the extreme; but that was all right. It was a joy ride for us. We laughed, sang, and shed tears of joy at our release from prison. We made a bee-line to Cairo, over three hundred miles through the finest corn region in the world. From Cairo we were sent down the Miss. River to Vicksburg and from there to Clinton Miss. Where we went into camp, electing officers, and re-enlisting for three years of the war. We were furnished our necessary equipment, for the Yankees had stripped us of everything except what we had on.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.