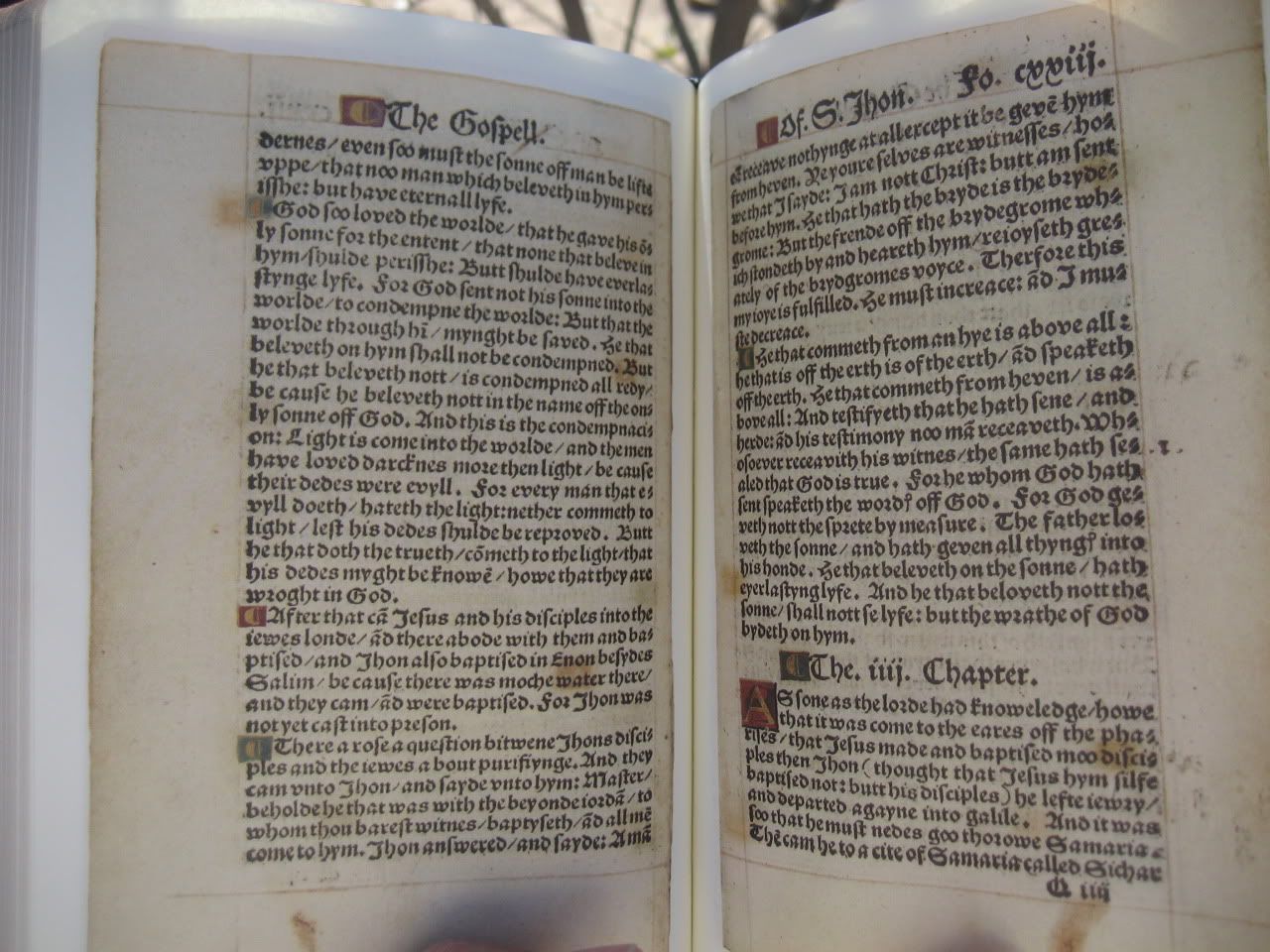

Tyndale's, per the British Museum.

Posted on 07/08/2011 8:20:58 AM PDT by SeekAndFind

If every committee did such impressive work, committees wouldn’t have a bad name.

Four hundred years ago, King James of England commissioned several dozen scholars to update and improve on prior translations of the Bible into English. Their handiwork — known as the King James Version — put an indelible stamp on the English language and on the Anglo-American mind.

The prodigious task took roughly six years. Just printing it was an undertaking. Initially, a typo appeared on average once every ten pages of text. One edition was called the “Wicked Bible” when the word “not” was accidentally left out of the admonition, “Thou shalt not commit adultery.”

Typographical struggles aside, the translation was inspired and came to seem almost unimprovable. It culled from prior English translations, forging a synthesis that rose at times to the level of poetry. As Benson Bobrick notes in his history of the Bible in English, Wide as the Waters, the King James Version stayed true to Hebraic turns of expression and kept language that was already archaic in the 17th century.

All of this gave it a majestic lift that swept away all competition in both England and America. One historian has written that “its victory was so complete that its text acquired a sanctity properly ascribable only to the unmediated voice of God; to multitudes of English-speaking Christians it has seemed little less than blasphemy to tamper with its words.”

An archbishop of Dublin scandalized a conference of clergy in the 19th century when he said of the King James Version, “Never forget, gentlemen, that this is not the Bible.” They needed reminding it was only a translation of the Bible.

The ascendant King James Version had a profound influence on the language. As Alister McGrath writes in his book In the Beginning, “It did not follow literary trends; it established them.” It made commonplaces of phrases that we have forgotten are biblical in origin: “to fall flat on his face,” “to pour out one’s heart,” “under the sun,” “sour grapes,” “pride goes before a fall,” “the salt of the earth,” and on and on. Without it, McGrath reckons, “there would have been no Paradise Lost, no Pilgrim’s Progress, no Handel’s Messiah, no Negro Spirituals, and no Gettysburg Address.”

The mere act of translating the Bible from Latin into the vernacular was a victory for freedom. According to Bobrick, “The first question ever asked by an Inquisitor of a ‘heretic’ was whether he knew any part of the Bible in his own tongue.”

Visionaries like John Wycliffe championed an English version of the Bible in the 14th century when even the clergy didn’t read it much. A proto-Reformation figure, Wycliffe was posthumously declared a heretic, his remains dug up and burned. William Tyndale, whose translation would become the basis of much of the King James Version, had to flee England and was eventually arrested by the authorities, tried for heresy, and burned at the stake.

The availability of the Bible in English, Bobrick notes, fostered commercial printing and a culture of reading. It created space for people — ordinary people, needing no official sanction or filter — to read and think about their faith and life’s profoundest questions. Ultimately, that undermined the authority of, to take another phrase from the King James Version (Romans 13:1), “the powers that be.”

“Free discussions about the authority of Church and state,” Bobrick argues, “fostered concepts of constitutional government in England, which in turn were the indispensable prerequisites for the American colonial revolt. Without the vernacular Bible — and the English Bible in particular, through its impact on the reformation of English politics — there could not have been democracy as we know it.”

The translators of the King James Version stated their “desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood of the very vulgar.” In a cultural triumph difficult to imagine 400 years later, it not only found a wide audience, but elevated it.

— Rich Lowry is editor of National Review.

I still prefer Tyndale’s. I read it to a youth Sunday School class a few months ago, and they didn’t realize it wasn’t a modern translation until I told them!

The KJV did two things wrong:

1 - It wanted to sound nobler to the tongue, so it was translated in a different style than the underlying Greek & Hebrew supports.

2 - It wanted to preserve a hierarchical church, so King James required them to use terms like ‘church’ and ‘bishop’ without regard for what the Greek said. As King James put it, “No Bishop, No King!”

From Tyndale, with modern spelling (and thou to you):

“Nicodemus said unto him: how can a man be born, when he is old? Can he enter into his mother’s body and be born again?

Jesus answered: verily, verily I say unto you: except that a man be born of water, and of the spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh, is flesh. And that which is born of the spirit, is spirit.

Marvel not that I said to you, ye must be born a new. The wind blows where he lists, and you hear his sound: but can not tell whence he comes and whither he goes. So is every man that is born of the spirit.

And Nicodemus answered and said unto him: how can these things be? Jesus answered and said unto him: Are you a master in Israel, and know not these things? Verily verily, I say unto you, we speak that we know, and testify that we have seen: And ye receive not our witness. If I have told you earthly things and ye have not believed: How should ye believe if I shall tell you of heavenly things?

And no man ascends up to heaven, but he that came down from heaven, that is to say, the son of man which is in heaven.

And as Moses lift up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the son of man be lift up, that none which believe in him perish: but have eternal life.

God so loved the world, that he gave his only son for the intent, that none that believe in him, should perish: But should have everlasting life. For God sent not his son into the world, to condemn the world: But that the world through him, might be saved. He that believes on him shall not be condemned. But he that believes not, is condemned all ready, because he believes not in the name of the only son of God.

And this is the condemnation: Light is come into the world, and the men have loved darkness more than light, because their deeds were evil. For every man that evil does, hates the light: neither comes to light, lest his deeds should be reproved. But he that does truth, comes to the light, that his deeds might be known, how that they are wrought in God.” - John 3

English is losing a lot of its grammar too -- it already lost during the Middle English period the usage of cases and gender allocation for non-animate nouns and now it is increasingly rare to see anyone knowing how to properly understand or frame a pluperfect sentence -- and we had thought that it had been adequately defined in stone...

***

whichever way, in both cases, the language is Early Modern English and is nearly outdated — if one reads Shakespeare for instance, the language is rapidly getting outdated too.

Here is a link to a well formated version of “From the Translators to the Reader”.

I have found that only larger Cambridge and modern aniversary reprints have it.

http://www.avbtab.org/av/avPre.htm

Here is where I get my KJV bibles,

http://www.bibles-direct.co.uk/

Their bibles are the best quality! Real English Cambridge and Oxford.

Do not order their legalistic sect song books as Allan has a long term contract to print them for a certain group.

The penalty for heresy in both Protestant and Catholic jurisdictions was, technically, death.

Tyndale believed himself to be safe in Antwerp for two reasons:

(1) Antwerp was a city where Catholics and Protestants mingled fairly freely, had an absentee ruler (the Duke of Brabant was also the Holy Roman Emperor and was not too focused on the day-to-day administration), and was governed by the city's assembly - which was more interested in commerce than theology.

(2) Antwerp was ruled by Charles V who, while no fan of Protestantism, had no desire to track down and kill the enemies of Henry VIII - whom he despised for divorcing his aunt, Queen Catherine.

Tyndale had written several pamphlets attacking the King's personal life and his Erastianism and was considered to be not just a heretic by England's new Protestant ascendancy, but also a personal enemy of the King.

However, with his fall from favor, King Henry VIII was not inclined to kill Tyndale. In fact, in August of 1535, Cromwell was given permission to write letters asking for clemency for Tyndale by the King’s authority. The appeal was turned down.

That is the spin - but Henry VIII and Cromwell wanted Tyndale dead while not offending his English supporters. So, unofficially, Cromwell sent his agent Henry Philips to inform on Tyndale to the authorities and threatened to expose the city fathers to punishment from the Emperor if they did not uphold the letter of the law. Then, officially and publicly, Cromwell cried out for leniency for Tyndale.

It was pure politics.

Cromwell knew that as long as no formal charges were made against Tyndale, the city and the emperor would not have lifted a finger against him. So Cromwell came up with a very clever solution in which the council and the emperor would have to execute Tyndale or look like they had lost all authority in their own lands. Great statecraft.

Around the same time that Cromwell was pretending to mourn Tyndale, he was having William Exmew drawn, quartered and disemboweled while still living for the "heresy" of recognizing the Pope.

“Saint” Thomas More pursued ‘heretics’ and had them tortured and killed at an unprecedented rate.

That's also completely false, by the way. Put under house arrest, absolutely. Tortured or killed? He had neither the legal authority to do so, nor has a single piece of evidence ever been put forward that he ever did such a thing.

Why are you posting facts? Can’t you let them get their 2 minute hate on in peace.

Yes...well, if we want modern, we’ll need for someone to come out with “The Texting Bible”.

To be honest, I’m surprised I haven’t seen one yet, although I would be incapable of reading it.

I DO have a Picture Bible though - we bought it for our granddaughter, but with modern trends, it may become a bestseller for adults!

http://www.amazon.com/Picture-Bible-Iva-Hoth/dp/0781430550/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1310144209&sr=8-1

However, besides that, English or rather American, Australia, Cockney etc. are all diverging and American in particular is both simplifying and grabbing words from other languages and redefining many other words

“Cromwell sent his agent Henry Philips to inform on Tyndale to the authorities and threatened to expose the city fathers to punishment from the Emperor if they did not uphold the letter of the law.”

Not Cromwell. Sorry. And Tyndale’s fortunes in King Henry’s mind went up and down. Anne Boleyn was a supporter of Tyndale, and didn’t fall from grace until after Tyndale’s arrest.

Tyndale had opposed her marriage, but he also supported the right of Kings against the Catholic Church, so he was neither for nor against King Henry. And indeed, shortly after Tyndale’s death, his New Testament was largely published by King Henry under the guise of Coverdale.

No one knows for certain who employed Philips, but his employment was more consistent with the views of More than of Cromwell.

“The penalty for heresy in both Protestant and Catholic jurisdictions was, technically, death.”

Yes, and under Thomas More, it was more likely to happen in England than in Belgium.

“Tortured or killed? He had neither the legal authority to do so, nor has a single piece of evidence ever been put forward that he ever did such a thing.”

Oh good grief! He most certainly did. More boasted of his hatred for heretics, and his desire to kill them all. It wasn’t a secret. He wrote at great length about it.

There is a question if he did so personally in his house - where he admitted to imprisoning heretics. But that heretics were tortured and burned with his approval, support and by his authority, there is no doubt.

“James Bainham was the son of a Gloucestershire Knight. He was a man well read in the classics and a distinguished lawyer of Middle Temple. He was too an earnest reader of Scripture. He was arrested by order of More, taken to his house in Chelsea, tied to the “tree of truth” where More caused him to be whipped in the hope of discovering other “heretics”. He was taken to the Tower where he was racked until he was lamed. When he was taken to the stake at Smithfield on 30th April 1531, he said “I die for having said it is lawful for every man and woman to have God’s book . . ..that the true key of Heaven is not that of the bishop of Rome, but the preaching of the Gospel.” At the stake, as the train of gunpowder ran towards him, Bainham lifted up his eyes towards Heaven and cried “God forgive thee and show thee more mercy than thou showest to me! The Lord forgive Sir Thomas More.”

“In More’s Confutation however, More states Tyndale is no longer a “heretic swollen with pride”- he is “a beast discharging filthy foam of blasphemies out of his brutish beastly mouth “- a “railing ribald” - a “drowsy drudge that has drunken deep in the devil’s dregs” and so on. (William Tyndale, R. Demaus).”

“Further burnings followed at More’s instigation, including that of the priest and writer John Frith in 1533. In The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, More described him as “the devil’s stinking martyr”

Newer translations have added a qualifier, which renders the passage almost meaningless.

I use the KJV, and our church uses the NAS. During readings, especially from the NT, I'm always amazed at how much is missing from the NAS. The NIV is even worse.

I have one of the Cambridge editions, Amazon, $5.

Both before and after More, it was deadly to be of any religion which differed from the King's own in England. When the King's religion became Protestant, it was deadly to be a Catholic. It was also deadly to be more Protestant than the King.

No one knows for certain who employed Philips, but his employment was more consistent with the views of More than of Cromwell.

Yes, indeed, Cromwell. Philips worked for Cromwell and was one of his agents on the Continent. He was also the man assigned by Cromwell to shadow Reginald and Geoffrey Pole in their European exile.

Why would an employee of Cromwell's be informing against Tyndale in Antwerp if Cromwell did not want him to? Why would an employee of More's be reporting to Cromwell about the movements of More's friend Cardinal Pole?

Anne Boleyn was a supporter of Tyndale, and didn’t fall from grace until after Tyndale’s arrest.

Anne Boleyn had no reason to support Tyndale, since he opposed the King's divorce on Scriptural grounds very publicly.

Oh good grief! He most certainly did. More boasted of his hatred for heretics, and his desire to kill them all.

That's funny, he never expressed such a desire for blood in any of his writings.

Quoting from Protestant propaganda texts against More is not probative.

What do the primary sources say? Nothing that supports the Black Legend.

Quite a bit of More's official paperwork survives, and it is - sadly for the propagandists - devoid of anything besides arrest warrants.

"Anne Boleyn had no reason to support Tyndale, since he opposed the King's divorce on Scriptural grounds very publicly."

She was a supporter of the Reformation and the translation of scripture into the vernacular.

"Anne Boleyn's personal copy of the English New Testament, featuring her coat of arms at the bottom."

"The Boleyn family had been instrumental in bringing the Scripture to the people in the English language. “Promoting the vernacular Bible was clearly a Boleyn family enterprise,” Eric Ives writes in The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn." (http://www.bollyn.com/the-english-bible)

"The Boleyn family had been instrumental in bringing the Scripture to the people in the English language. “Promoting the vernacular Bible was clearly a Boleyn family enterprise,” Eric Ives writes in The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn." (http://www.bollyn.com/the-english-bible)

"Quoting from Protestant propaganda texts against More is not probative."

He wrote a great deal, including many threats against Protestants (heretics). You might try reading what he wrote against Martin Luther, or the NINE VOLUMES he wrote against William Tyndale!

From http://www.ianpaisley.org/article.asp?ArtKey=thomasmore2:

Tyndale's friends and readers at home were another matter. There had been no burnings in England for eight years when More became chancellor. He soon put a stop to that. Heretics, he said, must be "punyshed by deth in ye fyre". He spun a web of spies and informers. He personally led house searches to track down Tyndale Testaments and the "nyght scoles of heresye" where Tyndale's "infeccyone" was spread.

The first victim was Thomas Hitton, a priest who had joined Tyndale and the English exiles in the Low Countries, and who had returned to England on a brief visit. He was seized near Gravesend in January 1530 as he made his way to the coast to take ship. Hidden pockets in his coat were found to hold letters "unto the evangelycall heretykes beyonde the see". At his interrogation, Hitton was true to the new beliefs. "The mass he sayed sholde never be sayed. Purgatory he denyed." He was burnt at Maidstone on February 23, 1530. Hitton had learnt his "false faith and heresies" from "Tyndale's holy books", More wrote, and he had become "an apostle, sent to and fro betwene our Englysshe heretykes beyonde the see and such as were here at home. The spirit of errour and lyenge hath taken his wretched soul with him strayte from the shorte fyre to ye fyre ever lastyng. And this is lo sir Thomas Hitton, the dyuyls [devil's] stynkyng martyr, of whose burnynge Tyndale maketh boste"...

...The chancellor, as the senior law officer in the kingdom, should have set an example in upholding these safeguards. Wolsey had done so. More broke them within six months of coming into office. A London leather seller named Thomas Philips was a typical suspect. More interrogated him personally in his Chelsea home, which he had equipped with stocks and a whipping tree. "I perceyued fynally the person suche that I could fynde no trouthe," More wrote, "a man mete and lykely to do many folkie mych harme." The jury which heard the case disagreed with More and refused to convict. More was obliged by law to release Philips immediately. Instead, the miserable man was excommunicated and committed to the Tower, where he languished for three years. John Field was held illegally in the Chelsea house for 18 days. More then had him sent to the Fleet prison, although no sentence had been passed against him or proof of heresy established. Field was in the Fleet for two years, in clear breach of statute. He complained that More often had him searched, sometimes at midnight, "besides snares and traps laid to take him in".

Another leather seller, John Tewkesbury, was said to have been pinioned "hand, foot and head in the stocks" at Chelsea for six days, and to have had "his brows twisted with small ropes, so that the blood started out of his eyes". Of his terrible death at Smithfield, More purred that Tewkesbury was "burned as there was never wretche I wene better worthy". Informers subsequently told him that Tyndale had praised Tewkesbury as a martyr. More commented that "I can se no very grete cause why but yf he rekened it for a grete glory that the man dyd abyde styll by the stake when he was faste bounden to it". He rejoiced that his victim was now in hell, where "Tyndale is like to fynde hym when they come together".

More's resignation as chancellor did not dim his hatred; it seemed evidence that Tyndale and his heretics were ushering the Antichrist into the seat of power. "I find that breed of men absolutely loathsome," he told Erasmus. "I want to be as hateful to them as anyone possibly can be; for my increasing experience with these men frightens me with the thought that the whole world will suffer at their hands."

In the case of John Frith, More used all the qualities of subtlety and manoeuvre that were later let loose on Tyndale. Frith was "ientle & quyet & wel lerned", a young scholar with a charm and grace that beguiled all who knew him. He had become an evangelical at Cambridge, and sailed for Antwerp. Here he had become Tyndale's closest and most loved friend, "my dear son in faith". Frith returned to England in secret to maintain contact with Tyndale's sympathisers. More got wind of this as Frith passed through London and on to Essex to take a ship back to Antwerp. A reward was put on his head and the roads close to the coast were watched. Frith was taken, like Hitton, as he neared the sea.

It seemed likely that Frith would survive. The king needed every theologian he could muster to support his marriage to Anne Boleyn, and he was impressed by reports of Frith's learning. Cromwell arranged for him to be kept in loose detention, unshackled, in the Tower. Frith had pen and paper; materials and correspondence were smuggled into him, and his completed writings were smuggled out. More seized on this to destroy him.Frith was asked by a friend to write his views on the Lord's Supper. This was very dangerous. Years before, Henry VIII had written a treatise defending the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, which holds that the Eucharist bread and wine are transformed into the real body and blood of Christ. The pope had rewarded him with the title of fidei defensor, defender of the faith - the title still appears as FD on modern coins. From Antwerp, Tyndale warned: "Of the presence of Christ's body in the sacrament meddle as little as you can..." But Frith wrote down his belief, denying the real presence of Christ. The treatise was passed to one of More's agents. More boasted of receiving two other copies, and a copy of Tyndale's letter to Frith as well.

More now used all his skills to ensure that the treatise would bring Frith the fate he planned for him. He no longer had the king's favour and could not bludgeon Frith with a public denunciation. Instead, he prepared a paper for private circulation entitled A Letter of Sir Thomas More, Knight, impugning the erroneous writing of John Frith against the blessed Sacrament of the Altar. It was targeted at the king. More was careful to flatter Henry for being "lyke a moste faythfull catholyke prynce for the avoydynge of suche pestylente bokes". A royal chaplain backed the letter up by preaching a sermon on the Eucharist in front of Henry, pointing out that there was a prisoner in the Tower at that moment who was "so bold as to write in defence of heresy".

Henry ordered Cranmer and Cromwell to have Frith brought for trial. Tyndale wrote him a farewell letter - "Your cause is Christ's gospel, a light that must be fed with the blood of faith. The lamp must be dressed and snuffed daily, and that oil poured in every evening and morning, that the light go not out... If the pain be above thy strength, remember: 'Whatsoever ye shall ask in my name, I will give it thee'" - and Frith was gone, the wind at Smithfield blowing the flames away from him, so that his dying was prolonged.

“Both before and after More, it was deadly to be of any religion which differed from the King’s own in England. “

A fair statement. There is a reason Baptists hate the idea of a State Church! Frankly, Calvinist or Catholic, in medieval times, it was extremely dangerous to differ from the state church wherever you were at!

A rational defense of More is to point out the times in which he lived, and the fears he had of another peasant’s revolt, only this time in England. But it defies More’s own words to pretend he didn’t seek to stamp out Protestants in England, or that he did not hate (loathe, strongly oppose) Tyndale. For a man of that time, and as busy as More was, to write 750,000 words by hand to oppose Tyndale is indicative of a passionate opposition.

I visited your "about" page and glad that I did. Talent abounds! It's nice to know that there are people out there like you. My family and I share your love of animals.

I will take your clumsy cut-and-paste job as an admission that you do not understand the concept of historical research.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.