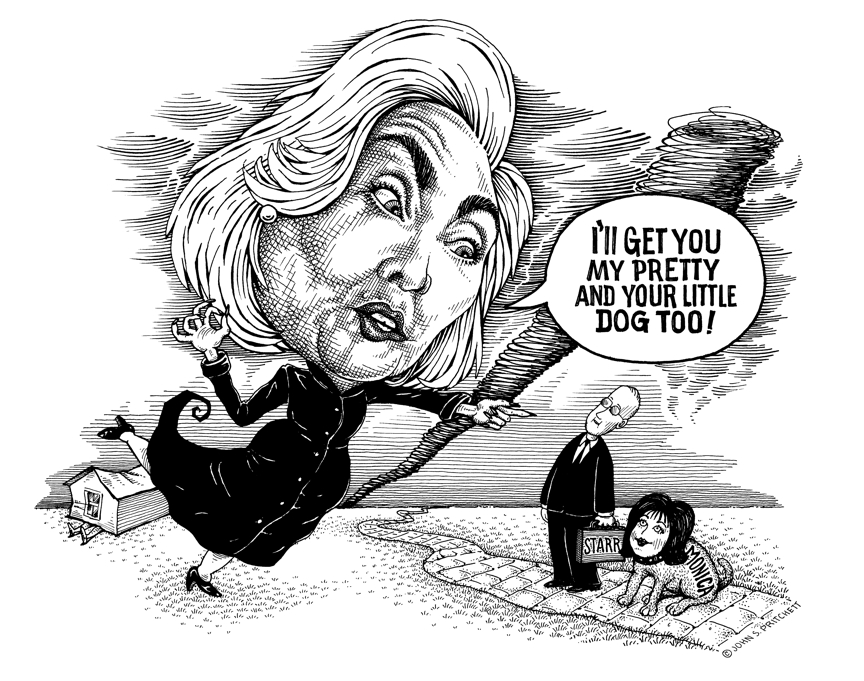

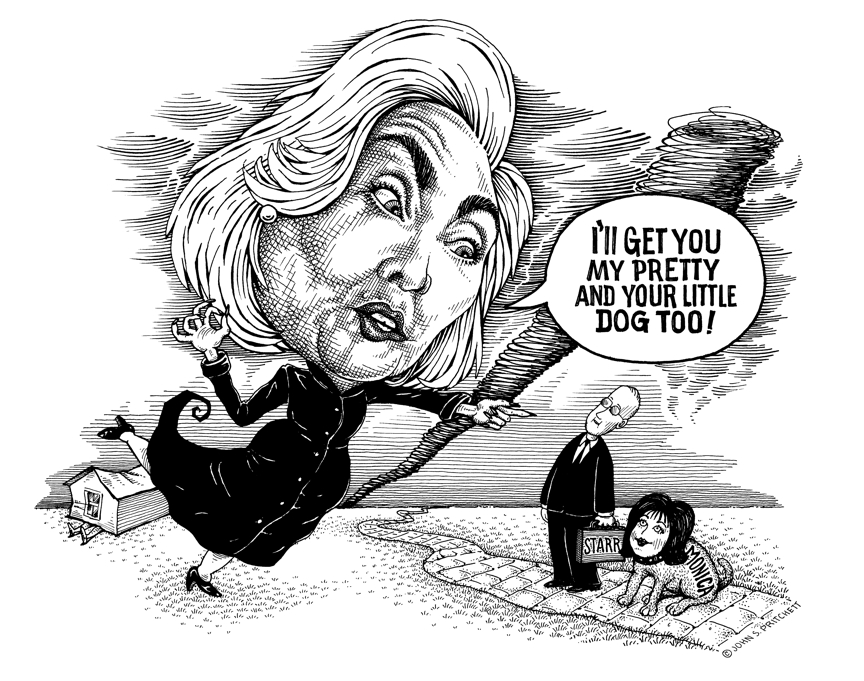

I thought she had her own 'Special' transportation ?? . . .

Posted on 05/07/2003 10:30:17 AM PDT by Remedy

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am grateful for the opportunity to share my views on the constitutional right of a Senate majority to confirm judicial nominees of the President irrespective of a supermajority Senate filibuster or cloture rule.

The Constitution establishes a simple majority as the Senate consensus sufficient to confirm nominees of the President who are officers of the United States under the Appointments Clause, including judges and members of the Cabinet. When the Constitution contemplates supermajorities, for example, to ratify treaties, to convict for impeachable offenses, or to override presidential vetoes, it employs express language to that effect. The absence of any supermajority language or hint of the same in the Appointments Clause confirms the obvious- that a simple majority was intended to confirm nominees. Indeed, no non-trivial argument has ever been fashioned that questioned the appointment of a federal judge or Cabinet officer who was approved by a Senate majority.

Appointments Clause policies are not advanced by a supermajority requirement for judicial nominees. As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist 76, the Senate's confirmation power was intended to safeguard against incompetence, cronyism or corruption, a task that can be discharged as well by a simple majority. In any event, the prevailing filibustering against two of President George W. Bush's nominees is fueled by ideological opposition, a ground beyond the purpose of confirmation scrutiny. Moreover, the power to appoint was entrusted to a unitary and accountable president instead of the Senate or a collectivity to promote excellence and integrity. As Hamilton amplified in Federalist 76: "The sole and undivided responsibility of one man will naturally beget a livelier sense of duty and a more exact regard to reputation. He will, on this account, feel himself under stronger obligations, and more interested to investigate with care the qualities requisite to the station to be filled, and to prefer with impartiality the persons who may have the faintest pretensions to them."

In contrast, the Founding Fathers understood that collective bodies invariably subordinate the public interest in glittering credentials to small-minded partisanship or uninspired horse trading in making appointments. Hamilton elaborated in Federalist 76: "There is nothing so apt to agitate the passions of mankind as personal considerations, whether they relate to ourselves or to others, who are able to be the objects of our choice or preference. Hence, in every exercise of the power of appointing to offices by an assembly of men we must expect to see a full display of all private and party likings and dislikes, partialities and antipathies, attachments and animosities, which are felt by those who compose the assembly. The choice which may happen to be made under such circumstances will of course be the result either of a victory gained by one party over the other, or of a compromise between the parties. In either case, the intrinsic merit of the candidate will be too often out of sight. In the first, the qualifications best adapted to uniting the suffrages of the party will be more considered than those which fit the person with the station. In the last, the coalition will commonly turn upon some interested equivalent: 'Give us the man we wish for this office, and you shall have the one you wish for that.' This will be the usual condition of the bargain. And it will rarely happen that the advancement of the public service will be the primary object of either party victories or of party negotiations."

Hamilton's lowest common denominator worry in appointments would be compounded, not mitigated, by a supermajority confirmation practice. It would place a perverse premium on nondescript and timid minds. And the same flaw would obtain for bipartisan commissioners in each state to present consensus nominees to the President. But constitutional law is too important to be left to mediocrities, notwithstanding former Senator Roman Hruska's celebration of the pedestrian.

Lawyers and the law are generally backwardlooking. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes sermonized, many judges need education in the obvious, and continue to parrot legal doctrines inherited from the time of Henry IV in blind imitation of the past. Enlightened jurisprudence requires

Judges credentialed with bold, long-headed and razor-sharp intellects who have mastered history, human nature, and the moral precepts that inform our constitutional dispensation. Prudence is equally imperative, without which knowledge is useless, wit ridiculous, and genius contemptible, to borrow from Sam Johnson's fount of epigrams.

Such individuals ordinarily challenge conventional wisdom and spur controversy. Justice Louis D. Brandeis is emblematic, and his confirmation in 1916 would probably have been scuttled if opponents had attempted to prevent a floor vote. A supermajority requirement would tend to block desperately needed brilliance on the federal bench and give the law earmarks of a petrified forest. It seems worth highlighting that there is no non-arbitrary supermajority stopping point once the constitutional standard of a simple majority is abandoned. Unanimity would be as undisturbing to the constitutional text and two centuries of practice as would be a 60 or 75 percent supermajority requirement. In other words, to accept the proposition that the constitution permits the Senate to require more than a simple majority for judicial confirmations is to endow the Senate with constitutional power to demand unanimity and lacerate the President's appointment authority.

An additional mischief of supermajorities is filling judicial vacancies. The more lead-footed the appointment process caused by the need for a supermajority consensus, the more understaffed the federal judiciary. Caseloads mount. Care in drafting opinions is slighted. More are unpublished than published. And litigants encounter frustration since justice delayed is justice denied. The arguments in favor of a supermajority cloture rule for the purpose of thwarting confirmation by a simple Senate majority are unpersuasive. It is said that Article I empowers the Senate to make internal rules governing its proceedings. But Senate rules cannot ignore constitutional imperatives. The clearest example would be a rule that refused to count the votes of black or female Senators.

A supermajority cloture rule is less clearly constitutionally stained, but clear enough. The constitutional text does not directly clash with a supermajority Senate rule. It tacitly declares a simple majority is sufficient, without expressly prohibiting an upward adjustment by Senate rule. But the purpose of the Appointments Clause- giving the president the star role with Senators serving as supporting actors in the appointment of federal judges- would be largely defeated by discretion in the Senate to impose a supermajority confirmation hurdle with no stopping point short of unanimity. That power would give the Senate equal billing with the President in appointing judges, contrary to what the clause envisions. Further, a Senate power by rule to amend the constitutional standard of majority confirmation would be startling since two thirds majorities in both the House and Senate and three fourths of the States must approve a constitutional amendment.

It is also said that a non-constitutional supermajority rule is proper to block judicial nominees outside the legal mainstream. This contention is counterfactual. President George W. Bush and his opponent Al Gore featured judicial appointments in their platforms and debates. The topic was recurring throughout the campaign. President Bush prevailed. Even discounting for the unique elements of his victory, it cannot be credibly said that a view on judicial nominations that captured support from approximately half the American people is extreme. In addition, confirmation of the President's judicial nominees was raised in several Senate races in 2002. Detractors of the President's philosophy in appointing judges were unsuccessful in retaining Democrat control. It shifted to Senate Republicans who generally saluted President Bush's standards for judicial appointments. In sum, it smacks of the Orwellian to characterize a mainstream view of the American people in appointing federal judges as a fringe outside the mainstream, like mistaking the Mississippi River for a diminutive tributary.

It is alternatively said that a supermajority is appropriate to prevent a president from filling judgeships with persons of the same or comparable judicial philosophies. But that has never been the Senate practice. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is illustrative. His ill-conceived court-packing plan was soundly rebuffed by Congress. The scheme sought to upset the traditional independence of the judiciary. But despite his resounding defeat on court-packing, FDR encountered no difficulty as vacancies arose in the ordinary course in packing the High Court with fervent New Dealers who generally supported the discredited court-packing legislation: Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, Frank Murphy, James Byrnes, Robert Jackson, and Wiley Rutledge. No effort was made in the Senate to defeat Roosevelt's nominees by filibustering or otherwise on the theory that a President is not entitled under the Appointments Clause to champion a particular judicial philosophy in all or most of his selections.

To reject on constitutional grounds a supermajority requirement for cloture regarding judicial nominees does not compel the same conclusion regarding legislation. The Founding Fathers worried about an excess of law making and erected barriers to that end, including a presidential veto. Filibustering to defeat legislation works towards that same constitutional end. In contrast, the Founding Fathers voiced no concern over the appointment of too many federal judges or judges echoing a uniform philosophy of judging. Filibustering judicial nominees with a supermajority cloture rule advances no constitutional objective or sentiment. Indeed, in the particular cases of two circuit court nominees now before the Senate, the filibustering wars with the constitutional goal of an independent judiciary to check legislative excesses. It is transparent that several pro-filibuster Senators aim to block confirmation of the nominees because fearful they might check congressional usurpations under either the Commerce Clause or section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. In other words, the filibusters are calculated to weaken judicial review of federal statutes.

Finally, it is every bit as important to the enlightened functioning of government that our unwritten constitution be as scrupulously honored as its written counterpart. Our unwritten constitution is a collection of self-restraining political customs necessary for the constitution itself to flourish. If partisanship and the power to disrupt were exploited to the extreme, then our sacred constitutional system and coveted separation of powers would collapse. The judiciary could be destroyed either by a President's refusal to nominate or the Senate's refusal to confirm, despite the absence of any express constitutional denunciation of either tactic. A President could mutilate a department created and funded by Congress by refusing to fill high level vacancies and making it acephalous. Or a president could de facto repeal criminal or civil laws through policies of non-prosecution. Congress might refuse to appropriate money to pay judicial salaries hoping to drive incumbents into resigning in order to denude the federal bench. For more than two centuries, a vital unwritten constitutional custom underpinning the Appointments Clause has been the non-filibustering of judicial nominees. To break with that tradition of comity with the executive branch would set a worrisome precedent that could trigger wider constitutional convulsions. There can be no doubt that the ongoing filibustering of two circuit court nominees is simply a dress rehearsal for thwarting President Bush's anticipated Supreme Court nominees- perhaps as early as July- where the political and constitutional stakes will be momentous. Those who would pursue this reckless obstructionist course are more to be dissuaded and overcome than praised and garlanded both for the living and those yet to be born.

If in the end, we must use parlimentary proceedure to revise or suspend the Rules of the Senate in order to execute the Senate's Constitutional duty, we must have first made the case that such a step is both necessary and right.

MR. STEVEN CALABRESI Professor of Law Northwestern University Law School

The people of the United States have just won a great victory in the war to bring democracy and majority rule to Iraq. Now it is time to bring democracy and majority rule to the U.S. Senate’s confirmation process for federal judges. A determined and willful minority of Senators has announced a policy of filibustering, indefinitely, highly capable judicial nominees such as Miguel Estrada and Priscilla Owen. By doing this, those Senators are wrongfully trying to change two centuries of American constitutional history by establishing a requirement that judicial nominees must receive a 3/5 vote of the Senate, instead of a simple majority, to win confirmation.

I have taught Constitutional Law in one form or another at Northwestern University for 13 years and have published more than 25 articles in all of the top law reviews including the Harvard Law Review, the Yale Law Journal, the Stanford Law Review, and the University of Chicago Law Review. I served as a law clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia and as a Special Assistant to the Attorney General of the United States. I am a Co-Founder and the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Federalist Society, a national organization of conservative and libertarian lawyers. I offer this legal opinion in my individual capacity, and not on behalf of my academic institution, the Federalist Society or any client.

The U.S. Constitution was written to establish a general presumption of majority rule for congressional decision-making. The historical reasons for this are clear. A major defect with the Constitution’s precursor, the Articles of Confederation, was that it required super-majorities for the making of many important decisions. The Framers of our Constitution deliberately set out to remedy this defect by empowering Congress to make most decisions by majority rule. The Constitution thus presumes that most decisions will be made by majority rule, except in seven express situations where a two-thirds vote is required. The seven exceptional situations where a super-majority is required include: overriding presidential vetoes, ratifying treaties, approving constitutional amendments, and expelling a member.

The Senate can always change its rules by majority vote. To the extent that Senate Rule XXII purports to require a two-thirds majority to invoke cloture on a rule change, Rule XXII is unconstitutional. It is an ancient principle of Anglo-American constitutional law that one legislature cannot bind a succeeding legislature. The great William Blackstone himself said in his Commentaries that "Acts of parliament derogatory from the power of subsequent parliaments bind not...". Thus, to the extent that the last Senate to alter Rule XXII sought to bind this session of the Senate its action was unconstitutional. A simple majority of the Senate can and should now amend Rule XXII by majority vote to ban filibusters of judicial nominations.

Leading scholars in this area of law such as John O. McGinnis of Northwestern University, Michael Rappaport of San Diego University, and Erwin Chemerinsky of the University of Southern California all have written that the Senate Rules can be changed at any time by a simple majority of the Senate. More importantly, Vice Presidents Richard M. Nixon, Hubert H. Humphrey, and Nelson A. Rockefeller have all so ruled while presiding over the United States Senate. Some commentators have gone even further in challenging filibusters of legislation as unconstitutional, as did Lloyd Cutler, White House Counsel to Presidents Carter and Clinton. Indeed, eight years ago, 17 very distinguished law professors, led by Yale Law Professor Bruce Ackerman, opined that a new Rule in the House of Representatives purporting to create a 3/5 requirement for enacting new tax increases was unconstitutional. The Ackerman letter wisely called for limiting the proliferation of new extra-constitutional, super-majority rules – counsel that the Senate should heed here.

What will happen if the filibuster is allowed to spread to the new area of judicial confirmations? It will next spread to the resolution every new Senate must pass to organize itself, set up Committees, and apportion staff and other resources. The filibusters next expansion will be one wherein a minority of 41 Senators will claim they are entitled to equal slots and Committee resources as are enjoyed by a majority of 59 Senators. This is the logical extension of the filibusters protection of minority rule under the inexorable Calhounian logic now being played out.

Have we not already seen this in the organizing resolution for the sitting Senate? They will not go quietly, but go they must.

Forgive me for reposting something that I wrote earlier on another thread. It is a concept that I would like to see have more discussion. ---

The unwillingness of Republicans to stand by 'our warriors' shows me that we have a lot of appeaseniks in our own party.

These appeaseniks keep thinking that if we are 'nice' to the dems, if we apologize profusely every time a Republican opens their mouth 'insensitively', we can get the Dems to go along with programs and bills in Congress.

GOP appeaseniks are treating the Dems like the left treated the USSR. We have to start treating the obstructionist party for what they are in reality --a virtual fifth column that would rather see our country sink than to remain out of power.

I thought she had her own 'Special' transportation ?? . . .

The unwillingness of Republicans to stand by 'our warriors' shows me that we have a lot of appeaseniks in our own party.

These appeaseniks keep thinking that if we are 'nice' to the dems, if we apologize profusely every time a Republican opens their mouth 'insensitively', we can get the Dems to go along with programs and bills in Congress.

GOP appeaseniks are treating the Dems like the left treated the USSR. We have to start treating the obstructionist party for what they are in reality --a virtual fifth column that would rather see our country sink than to remain out of power.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.