Posted on 12/22/2006 4:29:21 AM PST by Molly Pitcher

Continental Army General George Washington’s celebrated “Crossing of the Delaware” has been dubbed in some military circles, “America’s first special operation.” Though there were certainly many small-unit actions, raids, and Ranger operations during the Colonial Wars – and there was a special Marine landing in Nassau in the early months of the American Revolution – no special mission by America’s first army has been more heralded than that which took place on Christmas night exactly 230 years ago.

Certainly the mission had all the components of a modern special operation (though without all the modern battlefield technologies we take for granted in the 21st century): “A secret expedition” is how John Greenwood, a soldier with the 15th Massachusetts, described it, as quoted in Bruce Chadwick’s The First American Army.

If nothing else, all the elements for potential disaster were with Washington and his men as they crossed the Delaware River from the icy Pennsylvania shoreline to the equally frozen banks of New Jersey, followed by an eight-mile march to the objective – the town of Trenton.

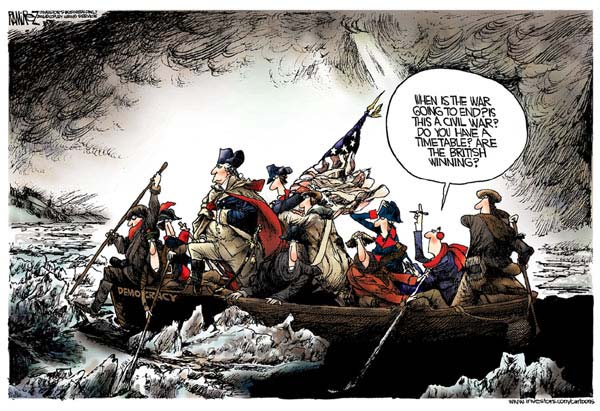

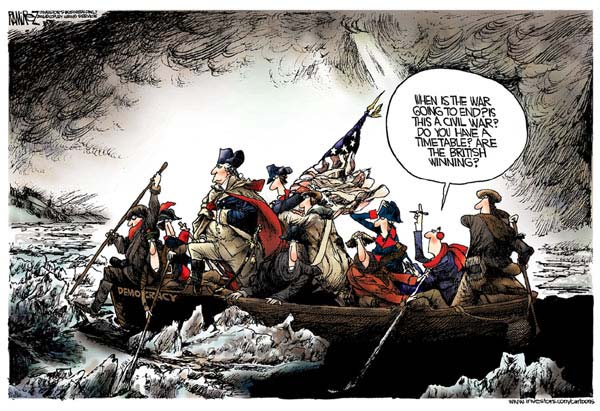

The river – swollen and swift moving – was full of wide, thick sheets of solid ice. And unlike the romanticized portrayal of the operation in the famous painting by Emanuel Leutze (the one with Washington standing in his dramatic, martial pose; his determined face turned toward the far side of the river), the actual crossing was made in the dead of night, in a gale-like wind and a blinding sleet and snowstorm. Odds are, Washington would have been hunkered down in one of the 66-ft-long wooden boats, draped in his cloak, stoically enduring the bitter cold with his soldiers, some of whom were rowing or poling the boats against the ice and the current.

WASHINGTON’S STRATEGIC CONCERNS

The decision for the crossing and the subsequent raid on Trenton was based on Washington’s belief that he had to do something. Otherwise – as he penned in a private letter – “the game will be pretty near up.”

To the easily disheartened and the cut-and-runners, it might have seemed “the game” was indeed already “up.” After all, many of Washington’s Continental Army were wounded, sick, and demoralized. Recent losses to the British had been severe. Desertion numbers were rising, and enlistment terms were almost up. Reinforcements were poorly trained and ill-equipped. Ammunition was in short supply. The soldiers were not properly outfitted for extreme winter conditions: Clothing was spare. Many men were in rags, some “naked,” according to Washington’s own account. Most had broken shoes or no shoes at all.

THE PLAN

The mission itself, though a huge gamble, was tactically simple.

Washington, personally leading a force of just under 2,500 men, would cross the river undetected, march toward Trenton, and attack the enemy garrisoned in the town at dawn.

Two of Washington’s other commanders, Generals John Cadwalader and James Ewing, were also directed to cross: Cadwalader’s force was to cross and attack a second garrison near Bordentown. Ewing’s force was to cross and block the enemy’s escape at Trenton. Both commanders, discouraged by the weather and the river, aborted their own operations. But according to Maurice Matloff’s American Military History (the U.S. Army’s official history), “Driven by Washington’s indomitable will, the main force did cross as planned.”

Speed of movement, surprise, maneuver, violence of action, and the plan’s simplicity were all key. And fortunately, the elements all came together.

The factors in Washington’s favor were clear: The weather was so bad that no one believed the Continentals would attempt a river crossing followed by a forced march, much less at night. The Continentals were numerically – and perceived to be qualitatively – inferior to the British Army. The Hessians, mercenaries allied to the British and who were garrisoned in Trenton, had a battlefield reputation that far exceeded their actual combat prowess. And no one believed the weary Americans would want to attempt anything with anyone on Christmas.

THE CROSSING

Hours before kickoff, Washington had his officers read to the men excerpts of Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis, a portion of which reads:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict the more glorious the triumph.”

By 4:00 p.m. the force was gathered at McKonkey's Ferry, the launching point for the mission. The watchword, “Victory or death,” was given. When darkness set in, the men climbed into the boats and began easing out into the black river.

Back and forth thoughout the night and into the wee hours of the 26th, the boat crews ferried the little army, a few horses, and 18 cannon across the Delaware. The crossing was complete by 4 a.m., but two hours behind schedule, and the temperatures were plummeting. At least two men, exhausted and falling asleep in the snow, froze to death.

ATTACKING TRENTON

The next obstacle was the march toward Trenton in blinding snow, sleet, even hail; and on bloody frostbitten feet. “Keep going men, keep up with your officers,” Washington, now on horseback, urged as he rode alongside his advancing infantry.

Just before 8:00 a.m., the advance elements of the American army were spotted on the outskirts of town by a Hessian lieutenant. But by the time he was able to sound the alarm, all hell was breaking loose. Americans were rushing into Trenton with fixed bayonets. The Hessians – some still in their underwear, and nearly all with hangovers from too much Christmas Day celebrating – were attempting to form ranks, but were quickly overrun. Many fled in a panic. Hundreds surrendered. Those who resisted were shot down or run through with the bayonet. The Hessian commander, Col. Johann Rall, was desperately trying to rally his men. But he was shot from his horse, and died later that day.

One of Washington’s junior officers, Lieutenant James Monroe was leading a charge against a Hessian position in the town, when he took a musket ball in the chest and collapsed. Amazingly he survived, and would ultimately become the fifth president of the United States.

The fighting lasted about an hour. Four Americans had been killed and ten-times as many Hessians lay dead in the snow. Some 900 enemy prisoners were rounded up, along with weapons, ammunition, and other desperately needed stores. And Washington’s victorious army was soon marching back along the river road to the waiting boats and the return crossing.

WHAT IT MEANT FOR AMERICA

Days later when many enlistments were up, Washington ordered his commanders to form ranks. He then rode out before the troops, and appealed to their sense of duty as well as the criticality of their fight:

“My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake … The present is emphatically the crisis which is to decide our destiny.”

Indeed it was in December of 1776, just as it is in December of 2006.

Washington held his little army together. Many of the continentals renewed their enlistments. They then capitalized on their Trenton victory with wins over the British at Trenton (the second go ‘round) on January 2, and Princeton on January 3.

The initial Delaware crossing and the raid on Trenton was the bold, high-risk shot-in-the-arm the nearly disintegrated American army needed in late 1776. The fighting was far from over, and there would be many setbacks for the Americans before the Treaty of Paris was signed formally ending the war in 1783. But the great Christmas night raid in 1776 would forever serve as a model of how a special operation – or a conventional mission, for that matter – might be successfully conducted. There are never any guarantees for success on the battlefield; but with a little initiative and a handful of good Americans, the dynamics of war can be altered in a single night.

The area that is now the state of Vermont (based on "vere mont" -- the French translation for "green mountain") was a disputed territory long before the revolution. The region between Lake Champlain in the west and the Connecticut River in the east had been subject to competing claims by three different British jurisdictions (the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Provice of New York, and the Province of New Hampshire) at various times as far back as the 1660s. Because of the rugged terrain and harsh climate, it was basically ungovernable by any of the three -- and the "Green Mountain Boys" under Ethan Allen was an informal militia that effectively functioned as the only legitimate form of government since its inception in 1770 (some years before the revolution began). The basic purpose of the militia at the time was to allow settlers in this region enforce their New Hampshire land titles against the wishes of the British government (which had awarded these lands to the Province of New York).

Allen and his fellow leaders of the Green Mountain Boys saw the success of the colonists in the American Revolution as a means to negotiate deals with both the British government and the new American government to secure the best arrangement with either one -- to have Vermont join either Lower Canada as a British colony or the new American government as a U.S. state. At the time, the status of Vermont was so uncertain that it was conspicuously absent from the original Thirteen States.

Vermont's historical influences can be seen even to this day -- as Vermont still has a reputation for being among the most libertarian of all states in the U.S.

I know this is a long-winded reply, but it's basically a long way of saying this: Ethan Allen may have carried out the raid on For Ticonderoga "in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress," but the Continental Congress had absolutely no authority over the Green Mountain Boys and would have been completely powerless to do anything if he had refused to carry out the raid (hence the captain's question to Allen about "by whose authority that he demanded it [the surrender of the fort].

Thank you for posting these facts about John Glover and the Marblehead Men!

However, I don't think that the Naval Special Warfare Command would agree that the Marbleheaders belong in the USMC lineage. NSWC has laid claim to Glover and his men as the antecedents of the Special Boat Squadrons.

(On a side note, one of my ancestors, Major Amos Morrill of the New Hampshire Grants, was with Allen and Arnold when they took Fort Ti by stealth in 1775. Of course, there's no mention in the family genealogy that specifies exactly where he was when Johnny Burgoyne's expeditionary forces showed up to retake possession, virtually unopposed, in 1777. (g) )

Merry Christmas bump!

Hmmm....

Thanx, but I am really not impressed w/whatever any stinkin' gub-mint entity thinx bout anything--fuggem!

Boyoboy, that's good! Thanks for posting...

Thank you--and all the best to you and yours this Christmas season!

BTTT

I wonder if he is related to my family. My grandfather, William Augustus Glover, was a Secret Service operative on the White House detail during the Teddy Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson administrations. My late mother would have probably known as she was the family historian. She put together a family book- I'll have to check.

He would've likely been your grandfather's grandfather. That shouldn't be too hard to check, but wouldn't such a famous ancestor as Gen. Glover be known in your family?

Thanks for the post and the ping.

Thanks PB for the ping. A sidebar, from the Icky-pedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_of_the_Armies

During his lifetime, George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) never held the rank "General of the Armies." During the American Revolution he held the title of "General and Commander in Chief" of the Continental Army.

George Washington was not answerable to Continental Congress or the President of Congress while he commanded the Continental Army. In that regard, George Washington was the only person in United States history to actively command with complete authority all military forces of the United States.

[and he was worthy of that level of trust and responsibility, perhaps uniquely so]

A year prior to his death, Washington was appointed by President John Adams to the rank of Lieutenant General in the United States Army during the Quasi-War, after he had left office as President of the United States. Washington never exercised active authority under his new rank, however, and Adams made the appointment mainly to frighten the French, with whom war seemed certain.

Making up for lost time, and to maintain George Washington's proper position as the first Commanding General of the United States Army, he was appointed, posthumously, to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by congressional joint resolution of January 19, 1976, approved by President Gerald R. Ford on October 11, 1976, and formalized in Department of the Army Special Order Number 31-3 of August 13, 1978, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1776. The appointment confirmed George Washington as the most-senior United States military officer - more senior than Pershing because the date of Washington's posthumous commission predates Pershing by 143 years, but still subordinate in rank to the Commander In Chief. By normal US Military policy and precedent, no person may be elevated in seniority before their original date of appointment or enlistment.

Since George Washington is considered to be the most senior military officer, permanently outranking all other military officers, except the Commander In Chief, it is inferred that Washington's rank is considered a six star general, but there has never been any six-star insignia authorized or manufactured, since the rank of a five star general has already been established.

If you like this synopsis, be sure to read "WASHINGTON'S CROSSING" by David Hackett Fischer. You'll love it.

It's really one of my favorite history books...would make a great movie. It seems like the screenplay is all there in the book, already written.

I live but two miles away from the site of THE Crossing. I will be there on Christmas day for the reenactment.

I thought the exact same thing about how great a movie would be of either book. Gibson's "The Patriot" was a good human interest story and visually appealing, but didn't do a thing for communicating history or making it understandable. Either of the two books would make great war movies.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.