Posted on 10/04/2006 9:30:29 AM PDT by lizol

Living in the past

Polish-Americans have a particular view of Poland that doesn’t exactly line up with the real thing. We eat pierogies, dance the obligatory polka at our cousins’ weddings, and call our grandparents by Polish names. But we don’t have it exactly right.

This Letter from Poland is by Amy Drozdowska. 04.10.06

That’s what I learned the first time I ever came to Poland. Even though I was able to eat my fill of Polish dumplings, I soon learned that polkas aren’t really that Polish, and that no one here - except maybe very tiny children - calls their grandmother Busia. Poles in Poland give me very puzzled looks with I talk about my Busia and Dziadzia. Which is actually incredibly disturbing. Being Polish has always been part of my identity, a key way to define myself in a country where identity can be pretty murky. In America, if you actually know where your family has come from, you probably cling to it tightly. If you have a point of origin, then you have name and a whole set of characteristics to go with it. A whole culture to claim. Stable ground to stand on. Otherwise you risk being just “American,” and no one’s really sure what that is.

That fact that I had a Busia and a DziaDzia instead of a grandma and grandpa made me Polish; it made me something. So if no one in Poland today actually calls their grandparents that – no grown reasonable adult, anyway - then where does that leave me? These names constituted for me a core of Polishness, an emotional center mixed with childhood memory and yearning for a place I’d never been,… yet a place I belonged to nonetheless. But on that first visit to Poland, I had to face a notion that, naively, had never even occurred to me:

Poland has moved on without us. We Polish-Americans live in an imaginary Poland, fixed in the past and altered by American culture.

Take the language. I thought the Polish my relatives spoke had given me a pretty good foundation. But it turns out that if I want to meet someone on the corner, I should be telling them to meet me na rogu; but instead I’m telling them to meet me na kornerze – So words I thought were Polish are actually English with a Polish accent.

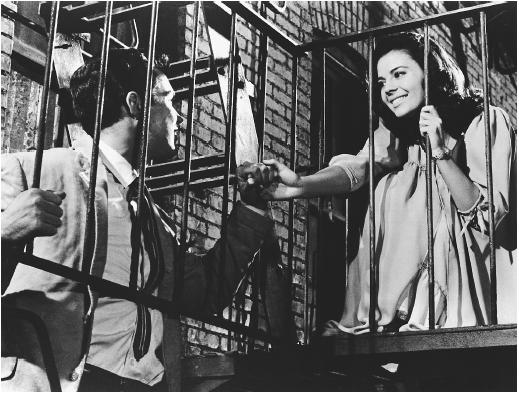

And there’s the picture of Poland we have in our heads. It’s either colored by folk costumes and paper cutouts, and the national flags red and white….or it’s completely in black-in-white.

All this only makes sense. The biggest wave of Polish immigration to the United States occurred just before World War I. My own family was part of that wave. My knowledge of Poland came in the form of food, Christmas customs, and grandparents who asked us questions in Polish and got our answers in English. My grandfathers and uncles drank beer and bowled at the White Eagle club. Growing up, I went to cousin’s weddings at banquet halls called again, White Eagle. My Polish last name, by any who dared an attempt to pronounce it, did so with the signature Polish-American surname ending: “-OWski.” It felt so ungainly and awkward-sounding - even a bit embarrassing. And it actually still does.

Now in Poland for my fourth time – and set to be here for the next year, I’m ready to grow up: to stop using out-of-date baby names to talk about my grandparents, and to open my eyes to a Poland that’s in full color, populated by people who wear chic European fashion and not folk costumes, and buildings that are trying to shed the drab, heavy Stalinist past. Well, some of them are trying. I’m ready – in fact I’ve been ready – to embrace the proper, more elegant pronunciation of my name.

Poland has changed many times over since my family could lay proper claim to it. The church where my great-grandmother was baptized was burnt to the ground in World War II. The dirt floors of my cousins’ houses – the ones my dad can’t stop talking about from his last visit here in the 1950s when he was 15 – they’ve been covered with same flooring you’d find in any average modern European home. The skyline of Warsaw continues to change form as new, tall buildings keep appearing.

Remember those Polish dumplings I mentioned, the ones I ate on my first visit to Poland? Well, they tasted amazingly, eerily like the ones my Mom makes. They brought back, in the only ways tastes and smells can, a certain slice of my own childhood - the safety and familiarity of family, of home populated by people I know better than anyone. And so there’s one thing that comforts me in this transition between the Poland I thought I knew and the Poland that actually exists, and Poland that in fact continues relentlessly to change: here in Warsaw I can still eat pierogies. And they still taste just like home.

Mine came from Missouri, but I'm not clinging onto St. Louis all that hard.

Being American is an identity. Please drop the hyphens.

So what do Poles call their grandparents? I called one set "Nana and Pop" and the other "Grandma and Grandpa." My children call my parents "Grandmama and Grand-dad."

Funny, the Poles (in Poland) want to be like Americans, the Americans, with vaguely Polish names, want to be what they think the Poles are or once were. Get back to where you never belonged, yeah!

You're wrong, Amy. You may not know what being "American" means, but the majority of us who don't pretend that our ancestry defines us are clear on it.

> Otherwise you risk being just “American,” and no one’s really sure what that is.

That's said like it's a bad thing.

Apart from citizenship, a proper respect for the Constitution and a loyalty to the United States, nothing else defines "American." Not race, not religion, not politics, not personal philosphy, not familiy history, not social status.

Being American is an identity.Yes, and a big part of that identity is the fact that we are the first nation in history based on a set of ideas instead of simply on a geographic location.

Part of that identity is the fact that our ancestors came from many places around the world to build the greatest nation in said world.

As Americans, we have these ideas in common, and many other things as well. One of those of course is our national language, which more recent immigrant "activists" are wrong to ignore or disparage the importance of.

But America is not a collective. It is a confederation of individuals. And yes, the national origins of our families are part of what makes us individuals, and there is absolutely positively nothing wrong with recognizing and celebrating them.

-Eric

I can never understand people like this writer. Both sets of my grandparents did everything short of outright murder to scrape enough money to emigrate from Sweden.

I am more genetically Swedish than a substantial number of Swedes. I can cook typical Swedish foods (typical if you lived on a farm 75 years ago). I can speak Swedish (but not well). And so what?

Sweden sucks, I've been there. The people live in dumpy little apartments. They eat generic Eurofood. They wear the same drab, ill-fitting fashions you can buy anywhere (except the business guys - they are sharp). They have less take home pay than I made mowing lawns as a kid.

I'm happy to be 100% American.

I am in total agreement, my great grandfather left Sweden for a reason....it really sucked! As did most immigrants, there is no place like The United States of America.

If you go to Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, or (so I'm told) Hawaii, the Japanese-Americans there have a similarly frozen culture. In some of the older businesses (those designed to appeal to Japanese-Americans as much as to Japanese tourists) the characters are all of the sort used before World War II, rather than the newer ones that the Japanese government adopted after the war. So too with some of the cuisine. And I suspect that Japanese-Americans who can speak Japanese but whose grandparents were born in the US probably speak in a way very different from the way young Japanese speak today. The culture is not any less "authentic" because the mother country has moved on, just different.

When most Polish immigrants came to US, Poland was still not even an independent country, the US gave them the freedom to assert their Polish identity in a way that they could not even do back in the Motherland.

Polish immigrants historically have been some of the most loyal to their adopted country. But that doesn't mean they had to forget about where they came from.

And the story goes that Milwaukee Avenue was first paved because Polish people went to City Hall in Chicago to complain that when their loved ones were on a cart going from Logan Square to St. Aldabert cemetery, the casket would fall off the wagon.

And what's the English translation of the name of the banquet hall across the street from St. Aldabert cemetery where everybody goes after a funeral, or after visiting a grave? White Eagle, or course.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.