Skip to comments.

‘I want to get off the plane.’ The passengers refusing to fly on Boeing’s 737 Max

Accuweather.com ^

| Mar 4, 2024

| Julia Buckley

Posted on 03/04/2024 10:56:46 AM PST by EinNYC

Ed Pierson was flying from Seattle to New Jersey in 2023, when he ended up boarding a plane he’d never wanted to fly on.

The Seattle resident booked with Alaska Airlines last March, purposefully selecting a flight with a plane he was happy to board – essentially, anything but a Boeing 737 Max.

“I got to the airport, checked again that it wasn’t the Max. I went through security, got coffee. I walked onto the plane – I thought, it’s kinda new,” Pierson told CNN. “Then I sat down and on the emergency card [in the seat pocket] it said it was a Max.”

He got up and walked off.

A flight attendant was closing the front door. I said, ‘I wasn’t supposed to fly the Max.’ She was like, ‘What do you know about the Max?’” he said.

“I said, ‘I can’t go into detail right now, but I wasn’t planning on flying the Max, and I want to get off the plane.’”

Pierson made it to New Jersey – after some back and forth, he said, Alaska’s airport staff rebooked him onto a red-eye that evening on a different plane. Spending the whole day in the airport was worth it to avoid flying on the Max, he said.

Pierson has a unique and first-hand perspective of the aircraft, made by Boeing at its Renton factory in the state of Washington. Now the executive director of airline watchdog group Foundation for Aviation Safety, he served as a squadron commanding officer among other leadership roles during a 30-year Naval career, followed by 10 years at Boeing – including three as a senior manager in production support at Renton itself, working on the 737 Max project before its launch.

But he’s one of a number of travelers who do not want to board the aircraft which has been at the heart of two fatal crashes, as well as the January 5 incident in which part of the fuselage of an Alaska Airlines plane blew out mid-air. The part – a door plug – was found to be missing four bolts that should have held it in place. Further reports of “many” loose bolts and misdrilled holes have emerged from the subsequent investigations into the Max 9 model after the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) ordered the grounding of 171 Max 9 aircraft with the same door plug.

Experts agree that the Alaska incident could have been worse, and the chair of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has warned that “something like this can happen again.”

The previous model, the Max 8, was involved in two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed a total of 346 people. The crashes were widely attributed to the malfunctioning of MCAS, an automated system in the Max designed to stabilize the pitch of the plane, overriding pilot input in some circumstances. Boeing accepted its liability in 2021 for one of the crashes.

Weeks after the Alaska incident, Boeing CEO David Calhoun told investors on a quarterly call: “We will cooperate fully and transparently with the FAA at every turn… This increased scrutiny, whether it comes from us or a regulator or from third parties will make us better.”

“We caused the problem, and we understand that,” Calhoun said. “Whatever conclusions are reached, Boeing is accountable for what happened. Whatever the specific cause of the accident might turn out to be, an event like this simply must not happen on an airplane that leaves one of our factories. We simply must be better.”

In February, in the wake of the Alaska incident, the company removed the head of the Max program from his position and reshuffled other senior management figures.

The move comes as critics have repeatedly said that the aircraft manufacturer is prioritizing profits over safety.

The FAA is now “taking a holistic look at the quality control issues at Boeing to ensure safety is always the company’s top priority,” a spokesperson for the government agency told CNN. Representatives are on the ground assessing the production lines at Boeing’s Renton factory and Spirit AeroSystems, whose Wichita, Kansas factory made the door plug that blew off mid-flight in the Alaska incident.

On February 28, the FAA gave Boeing 90 days to come up with a plan to address quality and safety issues.

Boeing told CNN: “Every day, more than 80 airlines operate about 5,000 flights with the global fleet of 1,300 737 MAX airplanes, carrying 700,000 passengers to their destinations safely. The 737 MAX family’s in-service reliability is above 99% and consistent with other commercial airplane models.”

Of course, many thousands of people board Max aircraft with no concerns. But do other passengers care? It appears that enough do.

Mixed impressions The last time the Max was grounded – for 20 months, following the crash of Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 on a Max 8 in March 2019 – 25% of the 1,005 Americans questioned in a Reuters/Ipsos poll said that they had “not a lot” or “no” confidence in the aircraft – compared to 31% who did, and 44% who were unsure. The poll was taken in December 2020, shortly before the aircraft’s return to the skies.

After being “told about the aircraft’s safety issues,” a further 57% said they would be somewhat unlikely or not likely to fly in a Max, according to the report. Nearly half – 45% – said that they would still be somewhat unlikely or not very likely to fly in it after it had been back in the air for six months. And 31% of all respondents said that they had little to no confidence that the Federation Aviation Administration (FAA) “puts passenger and crew safety first when determining whether an aircraft is fit to fly.”

Most countries cleared the Max 8 to fly again by 2021, but three years on, there still appears to be negative public opinion about the Max.

“It’s unsettling that there have been so many issues with this specific type of plane,” Stephanie King, a passenger on the affected Alaska Airlines flight, told CNN in January. “I hope something is done so that this doesn’t happen again.”

Then there’s flight booking site Kayak, which has seen usage of its filter to deselect Max aircraft (models 8 and 9) during the booking process increase 15-fold since January, the company told CNN. The site introduced the filter in March 2019, after the Ethiopian Airlines crash.

Doubts have also remained across the industry as a whole. Following the Alaska incident, a February AP-Norc poll regarding air travel safety found nearly a third of Americans surveyed answered “not at all” or “a little” when asked if they believe that airplanes are safe from structural faults. While planes were generally viewed to be as safe as cars or trains for means of transportation, fewer than two in 10 surveyed strongly agreed that planes are fault-free.

If it’s Boeing, ‘I ain’t going’ Belén Estacio has boycotted the Max since the January incident. Shortly after the Alaska Airlines fuselage blowout, she was scheduled on a Max for a work flight.

“My boyfriend didn’t want me to fly on it so I changed my travel plans to make sure I wasn’t flying on any type of Max,” she said.

“It doesn’t matter which model, I don’t want to fly them.” To her, she said, “The Alaska incident was further confirmation that Boeing is still not being thorough and not fixing its issues.”

Florida-based Estacio, who works in marketing, now checks the aircraft type before booking any flight. She’s made two trips since January.

“The whole thing of, ‘If it’s not Boeing I ain’t going,’ it’s totally the opposite now,” she said. “I’m very happy when I’ve seen I’ll be flying an Airbus.”

She says she’s not the only one in her circle, and says she knows people employing both “soft” and “hard” boycotts.

“Some say, ‘Absolutely not,’ others say, ‘If I can change it, I will; if not I’ll just go on it.’”

‘Not an aircraft I’d want to fly’ UK-based communications consultant Elayne Grimes is another with a personal boycott. Grimes, who travels regularly for work, was worried following the Max 8’s first crash in October 2018: Lion Air flight 610, in Indonesia, which killed all 189 onboard a plane in service for less than three months. Grimes – who’d previously worked in emergency crisis management – was immediately concerned about Boeing’s new aircraft, which had launched to great fanfare in 2017.

“I actively sought out airlines that didn’t have the Max,” she said. When Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 crashed in March 2019, killing another 157 people, it confirmed her resolve.

In 2022, Grimes watched “Downfall: The Case Against Boeing,” a Netflix documentary directed by Rory Kennedy, which looked at the two tragedies and flagged concerns about the working environment at Boeing.

“I watched that and thought [Boeing] was an organization putting profit before people, and thought, ‘That’s not for me.’ I don’t see myself flying one in the near future,” she said.

While the FAA has cleared the Max to fly once more, Grimes believes that “its issues are not resolved.”

“When the door came off and they called [the planes] in and found other aircraft with issues, I thought ‘Hmm,’” she said. “It’s just not an aircraft I’d want to fly.”

Grimes is a self-declared “avgeek,” or aviation fanatic – and she’s not the only one monitoring the industry closely to have reservations. Elliot Sharod, who says he took 78 flights last year, is on the fence. “I wouldn’t exactly refuse to fly it, but I’d ideally fly an Airbus if given the choice,” he said.

A former aviation journalist, who wished to remain anonymous for professional reasons, says they lost trust after the second crash.

“After the first one, the predominant talking points were, ‘Oh, it’s got to be pilot error, or the weather – it can’t be the plane,” they say. “It was Boeing. I believed that everything coming out of Boeing had been tested and retested – it had to be something else.

“Then the Ethiopian crash happened, and there was a bit of the same messaging, but finally it came out that actually it was the plane. I lost all trust at that point in the Max.”

They say they still love flying the “older style of Boeings – the 777s and the original 737s.”

“They were all designed back in the days when engineers ruled Boeing,” they say. “I feel I can trust them more than the Max.”

‘Piss poor design’ “Would you put your family on a Max simulator trained aircraft? I wouldn’t.”

They sound like the words of an anxious passenger in 2024. In fact, they were written by one Boeing employee to another in February 2018 – eight months before the Lion Air crash. (In the internal communications, their co-worker replied, simply, “No.”)

In April 2017, in internal messages by Boeing employees working on the soon-to-be-released Max, another employee wrote, “This airplane is designed by clowns, who in turn are supervised by monkeys.” The same exchange included a reference to the aircraft’s “piss poor design.” A design tweak was labelled as “patching the leaky boat.”

These internal communications were released as part of the 18-month investigation into the Max by the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. In a 238-page report, released in September 2020, the committee outlined “the serious flaws and missteps in the design, development, and certification of the aircraft.” The report highlighted five key themes, including “production pressures that jeopardized the safety of the flying public” and a “culture of concealment” at Boeing.

At the time, Boeing said that the communications “do not reflect the company we are and need to be, and they are completely unacceptable.” The company issued a statement acknowledging the committee’s findings and saying that the victims of the crashes were “in our thoughts and prayers.”

Boeing said that when the Max 8 returned to service it would be “one of the most thoroughly scrutinized aircraft in history, and we have full confidence in its safety.”

It added: “We have been hard at work strengthening our safety culture and rebuilding trust with our customers, regulators, and the flying public… We have made fundamental changes to our company… and continue to look for ways to improve.”

The House Committee report also included concerns about the FAA and its “grossly insufficient oversight” over Boeing during the Max design process and in the period between the two crashes. The report said that “gaps in the regulatory system at the FAA… allowed this fatally flawed plane into service.”

A spokesperson for the FAA told CNN: “The FAA made significant improvements to its delegation and aircraft certification processes in recent years and took immediate action following the Jan. 5 Alaska Airlines door plug incident to address concerns about the quality of aircraft that Boeing and its suppliers produce.”

‘Vindicated’ after safety failure Rory Kennedy followed the investigation from start to finish. The director of “Downfall” told CNN she didn’t have a “strong opinion” on the plane until she started making the documentary in early 2020.

But, she said, “I was shocked by what we discovered… [it] was really disturbing.”

Her film is a forensic investigation of the two crashes. “Downfall” interviews ex-Boeing staff and concerned pilots, who paint a picture of an accident waiting to happen. It follows the congressional hearings held as part of the House investigation, and interviews the victims’ families.

Kennedy says that during the design process Boeing “went to great pains to hide [MCAS] and how powerful it was.” The stabilizing system was designed specifically for the Max, since the fuel-efficient engines being added to the 1960s-designed plane affected the trim. The House committee found that Boeing concealed its existence from the FAA, airlines and pilots.

Additionally, after the Lion Air crash, FAA analysis in December 2018 predicted that without a software fix, a Max could crash on average once every two years over the course of its usage. Yet the plane was not grounded at the time.

“Boeing and FAA both gambled with public safety,” House committee chair Peter DeFazio said in a 2020 statement.

IF YOU WANT TO READ THE REST OF THIS VERY LONG ARTICLE, GO TO THE URL.

TOPICS: Travel

KEYWORDS: 787max; aircraft; boeing; boeing787; rotteneggs

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-25 next last

I don't know if this gross negligence stems from cost cutting measures in quality control, using inferior materials, or hiring less than qualified foreign engineers, but this is really scary.

1

posted on

03/04/2024 10:56:46 AM PST

by

EinNYC

To: EinNYC

DEI = DIE......................

2

posted on

03/04/2024 11:01:26 AM PST

by

Red Badger

(Homeless veterans camp in the streets while illegals are put up in 5 Star hotels....................)

To: EinNYC

The Max was designed with disproportionate input from bean counters, with predictable results.

To: EinNYC

Refer to the boeing doc on Netflix. They did this to themselves and deserve what is happening. Its too bad it takes people losing their lives to bring about change.

To: EinNYC

If there is an incident, you could get $1,500 from the airline. The tricky part is to survive it.

5

posted on

03/04/2024 11:07:18 AM PST

by

Tai_Chung

To: EinNYC

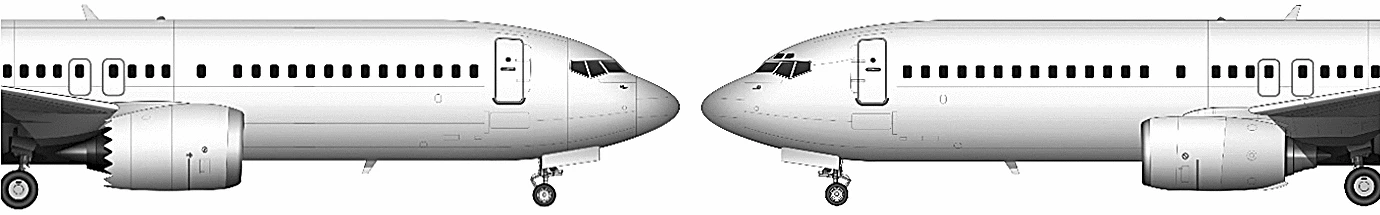

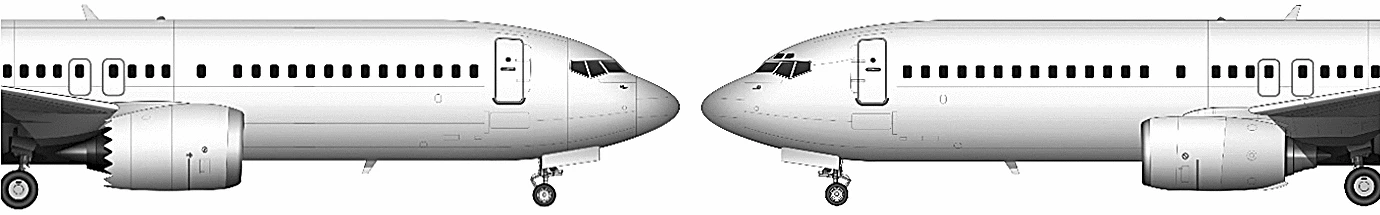

[Boeing 737 Max

He got up and walked off.]

I don’t blame him. I don’t want to fly on an A/C that had to have software correct for the fact that the center of gravity was messed up from installing engines that are too large for the plane and had to be moved forward.

Plus the other problems.

6

posted on

03/04/2024 11:07:27 AM PST

by

SaveFerris

(Luke 17:28 ... as it was in the Days of Lot; They did Eat, They Drank, They Bought, They Sold ......)

To: EinNYC

Would someone ping me to the posts from the Boeing social media team so I don’t have to read through the whole thread this evening?

Thanks.

7

posted on

03/04/2024 11:11:50 AM PST

by

PAR35

To: EinNYC

“If it’s Boeing, ‘I ain’t going’ ... “It doesn’t matter which model, I don’t want to fly them.” “

Good luck with that ... 43% of the commercial planes flying in the U.S. are Boeing.

To: DarrellZero

Design change to increase passenger capacity and not have to design a new plane, which would have required all their pilots to be retrained on a new plane design.

So, they threw these huge jet engines which are too large(by diameter) to fit under the wing. Solution was to move them forward. That changed weight balance and required software to “fly” the out of balance aircraft so it didn’t crash. Well oops it did a few times!

9

posted on

03/04/2024 11:16:29 AM PST

by

9422WMR

To: EinNYC

10

posted on

03/04/2024 11:19:03 AM PST

by

Grampa Dave

(“Surrender means wisely accommodating to what is beyond our control.” — Sylvia Boorstein.)

To: EinNYC

Sounds like the gobs putting the planes together are lazy

11

posted on

03/04/2024 11:22:55 AM PST

by

Nifster

( I see puppy dogs in the clouds )

To: Tai_Chung

If there is an incident, you could get $1,500 from the airline. The tricky part is to survive it. I had a puddle jumper airline flight from the midwest to Dallas a few years ago. The plane had to divert because of pressurization alarms. We had a six hour delay for another plane to show up. I got 10K miles accredited to my miles account. If I was an Alaskan mileage customer I would expect a bit more in the way of compensation..

12

posted on

03/04/2024 11:26:41 AM PST

by

EVO X

( )

To: EinNYC

There was a marked decrease in the quality of Boeing products when the head office was moved from Seattle to Chicago.

This is just a further outgrowth of that corporate decision.

13

posted on

03/04/2024 11:31:59 AM PST

by

Don W

(When blacks riot, neighborhoods and cities burn. When whites riot, nations and continents burn)

To: EinNYC

The move comes as critics have repeatedly said that the aircraft manufacturer is prioritizing profits over safety. When the Alaskan Airlines thing happened with the door, the story going around on conservative websites was that Boeing had subcontracted a DEI company that manufactured the doors. I scanned the article very quickly and did not see that mentioned anywhere.

To: EinNYC

None of those things.

To keep up with its main Airbus competitor (on fuel economy), Boeing elected in 2011 to modify the latest generation of the 737 family, the 737NG, rather than design an entirely new aircraft. The 737 MAX was an updated version of the 737 workhorse that first began flying in the 1960s. This raised a significant engineering challenge: how to mount the larger, more fuel-efficient engines (similar to those employed on the Airbus A320neo) on the existing 737. The original 737 family used low-bypass engines and was built closer to the ground than the Airbus A320.

To provide appropriate ground clearance, <>the larger, more efficient engines had to be mounted higher and farther forward on the wings than previous models of the 737. This significantly changed the aerodynamics of the aircraft and created the possibility of a nose-up stall under certain flight conditions.

(The Boeing 737 MAX: Lessons for Engineering Ethics, 10 July 2020.)

R. John Hansman, a professor of aeronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

...in high angles of attack the Nacelles -- which are the tube shaped structures around the fans -- create aerodynamic lift. Because the engines are further forward, the lift tends to push the nose up -- causing the angle of attack to increase further. This reinforces itself and results in a pitch-up tendency which if not corrected can result in a stall. This is called an unstable or divergent condition. It should be noted that many high performance aircraft have this tendency but it is not acceptable in transport category aircraft where there is a requirement that the aircraft is stable and returns to a steady condition if no forces are applied to the controls.

Boeing's fundamental design mistake was with the size and placement of the 737 MAX engine because of the potential for aerodynamic instability caused by its engine. This is an appropriate design for high-performance aircraft, but inappropriate for passenger aircraft.

To counter this inherent design instability, Boeing installed the MCAS software that pushed the nose down if it detected an unstable angle of attack...but did NOT tell any airline or pilot about the system.

After the crashes, Boeing proposed to modify the MCAS to require that both AOA sensors deliver similar readings -- they must be within 5.5 degrees -- before triggering the MCAS to tip down the nose. Boeing's fix would also limit how sharply the MCAS can tip the nose down -- to no more than flight crew can counteract by pulling back on the control column in the cockpit. The fix would only allow the MCAS to tip down the nose once, rather than repeatedly -- as the current version does -- thus making it easier for pilots to recover.

Note that the MAX had only TWO Angle of Attack sensors rather than three, so the system was inherently susceptible to AOA sensor failure. If the system gets two different readings from the two AOA sensors, which should it use?

In the October 29, 2018, Lion Air flight JT610 crash, the flight data recorder showed that MCAS forced the nose of the aircraft down TWENTY SIX times in 10 minutes. The pilots fought the MCAS all the way down.

Bottom line...Boeing management thought that they could compete with Airbus by installing the large high-efficiency, low fuel consumption engines on the 737 in an inherently unstable location higher up and more forward. They decided to do that rather than design a completely new aircraft. They decided to compensate for the inherent instability through software that was not disclosed or trained to airlines and pilots.

It was executive leadership failure.

15

posted on

03/04/2024 11:41:16 AM PST

by

ProtectOurFreedom

(“Occupy your mind with good thoughts or your enemy will fill them with bad ones.” ~ Thomas More)

To: EinNYC

Boeing has been suckling off the gubmint teat for decades. Its systemic in the most valid use of the word.

16

posted on

03/04/2024 11:43:56 AM PST

by

Delta 21

(If anyone is treasonous, it is those who call me such.)

To: EinNYC

I think I see the problem with the MAX program: Boeing hired idiots like this to work on the program.

He couldn’t tell it was a 737 MAX from the window before boarding? I don’t even work for Boeing or in the aviation industry and can spot a MAX from the window. The engine chevrons (and nacelle size/shape), the winglets and the APU area are quite different than the 737 NG.

I think if I was that terrified to board one these planes, I’d at least learn what they look like and look out the window before boarding it instead of waiting to view the safety card after being seated.

I wonder how many incorrect cars he’s sat in when ordering an Uber. Why check the license plate? Just get into the car.

17

posted on

03/04/2024 11:50:56 AM PST

by

OA5599

To: EinNYC

The 737 MAX software was written by Indians.

18

posted on

03/04/2024 11:56:04 AM PST

by

jroehl

(And how we burned in the camps later - Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - The Gulag Archipelago)

To: jroehl

“ The 737 MAX software was written by Indians.”

*********************

That wouldn’t surprise me at all.

19

posted on

03/04/2024 11:57:03 AM PST

by

House Atreides

(I’m now ULTRA-MAGA. -PRO-MAX)

To: 9422WMR

No modern passenger airliners have engines directly under their wings. Take a look at the Airbus A320’s and the previous generation 737 NG’s engine placement. They are all forward of the wings.

With the statement you made, I doubt you would be able to tell exactly how much further forward the LEAP engines on the MAX are than the CFM-56 engines on the NG.

MCAS wasn’t in response to weight distribution of the larger engines being moved forward. Think about it. Shifting weight further forward of the center of lift would require trimming the nose up. The MCAS only trims the nose down. So you may wish to work on your logic a bit.

Also, the larger fan diameter is for increased efficiency, not for more passenger capacity. Turbofan diameters have increased drastically over the decades. The original low bypass turbofans on the 737-100/200 look like cigars and actually did fit under the wings.

That generation of 737 (“Jurassic”) was supplanted by the 737-300/400/500 “Classic” series with the high bypass CFM-56 turbofans mounted ahead of the wings… in 1984. And then Airbus put those same engines in the same place a few years later on their new A320 family. That’s where the engines go now, even for the big jets like 777’s and A350’s.

20

posted on

03/04/2024 12:14:24 PM PST

by

OA5599

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first 1-20, 21-25 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson