We’ve known for a while about the large-scale structure of the Universe. Galaxies reside in filaments hundreds of millions of light-years long, on a backbone of dark matter. And, where those filaments meet, there are galaxy clusters. Between them are massive voids, where galaxies are sparse. Now a team of astronomers in Germany and their colleagues in China and Estonia have made an intriguing discovery.

These massive filaments are rotating, and this kind of rotation on such a massive scale has never been seen before.

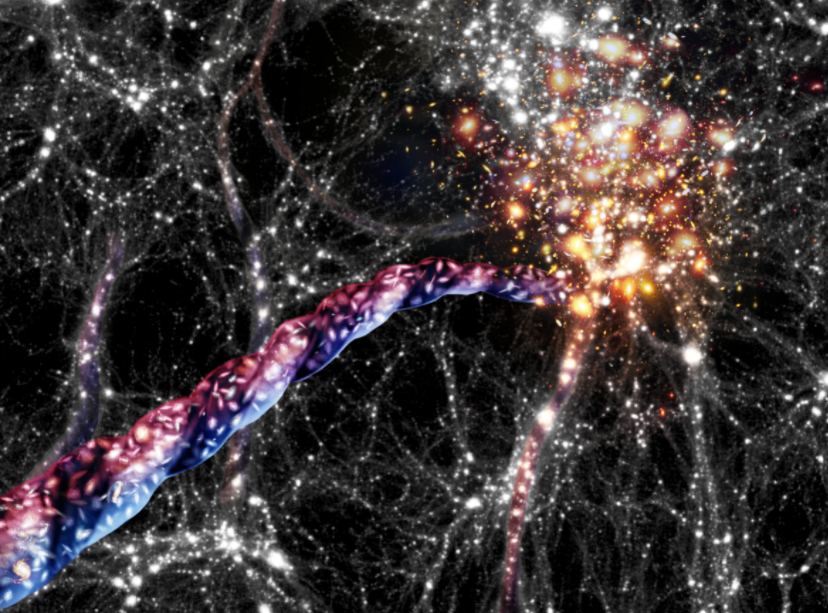

Obviously, there’s no way to take an actual picture of the Universe’s large-scale structure. But there are some almost-famous images that come from the Millennium Simulation Program. The Millennium Simulation was a super-computer simulation of a cubic portion of the Universe over 2 billion light-years on each side. The image contains about 20 million individual galaxies organized in filaments and clumps, and it was our first real glimpse of the Universe’s LSS.

It’s remarkable to look at that image now and imagine those filaments rotating. Image of the large-scale structure of the Universe, showing filaments and voids within the cosmic structure. Credit: Millennium Simulation Project

Image of the large-scale structure of the Universe, showing filaments and voids within the cosmic structure. Credit: Millennium Simulation Project

The team of astronomers behind this discovery worked with data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS.) The SDSS created a very detailed 3D map of the Universe, so SDSS data was critical to the team’s discovery.

“By mapping the motion of galaxies in these huge cosmic superhighways using the Sloan Digital Sky survey – a survey of hundreds of thousands of galaxies – we found a remarkable property of these filaments: they spin.” says Peng Wang, first author of the now published study and astronomer at the AIP (Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam).

Each of the galaxies in the filaments amounts to no more than a speck of dust on the grand scale, and they’re not only rotating but moving along the tendrils as if they’re pipelines.

“They move on helixes or corkscrew like orbits, circling around the middle of the filament while travelling along it.”Noam Libeskind, Study Co-Author, AIP.

“Despite being thin cylinders – similar in dimension to pencils – hundreds of millions of light years long, but just a few million light years in diameter, these fantastic tendrils of matter rotate,” added Noam Libeskind, initiator of the project at the AIP. “On these scales the galaxies within them are themselves just specs of dust. They move on helixes or corkscrew like orbits, circling around the middle of the filament while travelling along it. Such a spin has never been seen before on such enormous scales, and the implication is that there must be an as yet unknown physical mechanism responsible for torquing these objects.”

The fact that these filaments spin is difficult to visualize, and fascinating once you succeed. But the discovery is about more than our own fascination. These are the largest objects we’ve ever seen spinning, and that means that angular momentum can take place on a massive scale. One of the mysteries in cosmology is how that angular momentum is generated on such a massive scale since there was no primordial rotation in the early Universe.

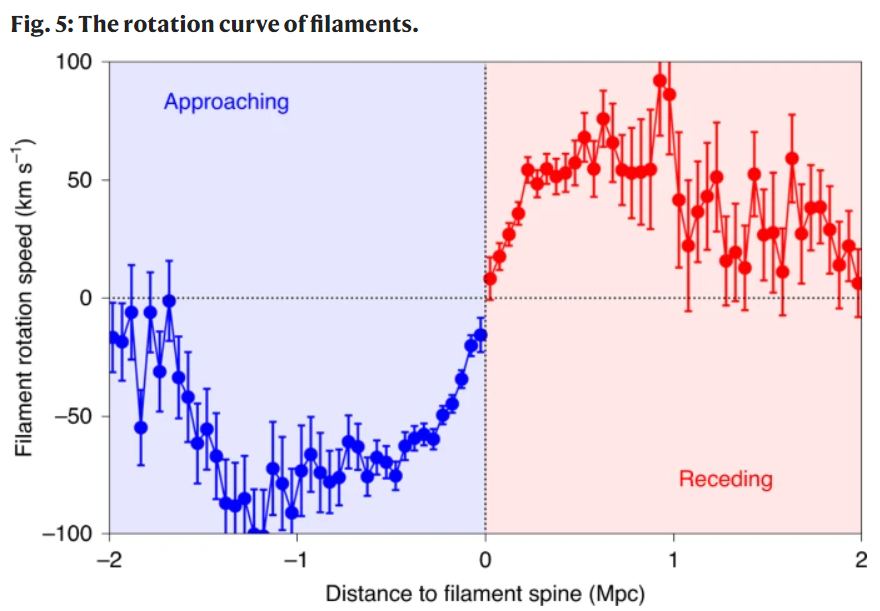

The discovery rests on observations of individual galaxies in the filaments and their Doppler shift. In this study, red-shift is a proxy for rotation, Red-shifted galaxies are receding, and blue-shifted galaxies are approaching.  This figure from the paper shows the filament rotation speed as a function of the distance between galaxies and the filament spine. The distance of galaxies from the filament spine in the receding region is displayed in red and ascribed positive values, while the distance of galaxies in the approaching region is marked in blue and ascribed negative values. Error bars represent the standard deviation about the mean. Image Credit: Wang et al 2021.

This figure from the paper shows the filament rotation speed as a function of the distance between galaxies and the filament spine. The distance of galaxies from the filament spine in the receding region is displayed in red and ascribed positive values, while the distance of galaxies in the approaching region is marked in blue and ascribed negative values. Error bars represent the standard deviation about the mean. Image Credit: Wang et al 2021.

In the current working model of the Universe’s structural formation, overdensities grow via gravitational instability. Material from underdense regions flows into regions of overdensity. But that flow of material has no rotation or curl to it. That’s why cosmologists say that there was no rotation in the early Universe. And here’s where this discovery gets more interesting.

The rotation evident in these filaments of galaxies must be generated as the structures form. And these filaments and the rest of the cosmic web are connected to the formation and evolution of galaxies themselves. They also have a powerful effect on the spin of individual galaxies and can regulate how a galaxy and its dark matter halo rotate. There’s an unknown piece in all of this: scientists don’t yet know how our current understanding can predict that the filaments themselves spin.

“Such a spin has never been seen before on such enormous scales, and the implication is that there must be an as yet unknown physical mechanism responsible for torquing these objects.”Noam Libeskind, Study Co-Author, AIP.

Before this study, other scientists have theorized that these filaments spin. For example, Dr. Mark Neyrinck, a Fellow at the Department of Theoretical Physics at the University of the Basque Country, Spain, is known for theorizing on this. He’s also known for developing the “origami” description of cosmic structure formation. In a 2016 article in The Paper he said, “…if galaxies rotate (and they do), so must filaments sticking out of them. Furthermore, galaxies joined by a filament should rotate mostly together, like objects attached to the ends of a rod. In fact, this is consistent with astronomical observations; nearby galaxies tend to be spinning in the same direction.”

Dr. Neyrinck’s work was an important starting point for the team behind this paper.

“Motivated by the suggestion from the theorist Dr. Mark Neyrinck that filaments may spin, we examined the observed galaxy distribution, looking for filament rotation,” says co-author Noam Libeskind. “It’s fantastic to see this confirmation that intergalactic filaments rotate in the real Universe, as well as in computer simulation.”

The team used a sophisticated mapping method that divided the observed galaxy distribution into segments. Then each of the filaments was approximated by a cylinder. The galaxies in the filament were then divided into two regions on either side of the filament’s spine. Then they carefully measured the mean redshift difference between the two regions. “The mean redshift difference is a proxy for the velocity difference (the Doppler shift) between galaxies on the receding and approaching side of the filament tube,” the authors write. That’s how they measured the filaments’ rotation.

In their paper, the team writes that what they found cannot be random. “What is measured and presented here is the redshift difference between two regions on either side of a hypothesized spin axis that is coincident with the filament spine. The full distribution of this quantity is inconsistent with random regardless of the viewing angle formed with the line of sight…”

However, the researchers caution, their results don’t imply that every filament in the Universe is rotating. That would be an over-reach. “This work does not predict that every single filament in the Universe is rotating,” they write, “rather that there are subsamples—intimately connected to the viewing angle end point mass—that show a clear signal consistent with rotation. This is the main finding of this work.”

“Taken together,” the team writes in their conclusion, “the current study and <references> demonstrate that angular momentum can be generated on unprecedented scales, opening the door to a new understanding of cosmic spin.”

Lead author of this work is Peng Wang, an astronomer at the Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP). The title of the paper is “Possible observational evidence for cosmic filament spin.” It’s published in Nature Astronomy.