Skip to comments.

Mysteries set in stone

Capital Journal ^

| 22 Aug 2014

| David Rookhuyzen

Posted on 09/02/2014 10:25:42 AM PDT by Theoria

They are mystery stories, written large as life in mineral ink on the pages of the northern plains.

A 360-foot snake – reportedly once with a blazing red tongue – slithering along a grassy slope. A long-tailed turtle lying next to woman near an earthen mound. A large grid spread across the spur of a hill. All created from lines of small boulders.

Hundreds of these stone effigies or alignments, ranging from animal forms to mosaics can be found across the seven Midwestern states and parts of Canada, including more than a hundred such figures in South Dakota. The mystery surrounding them has cast archaeologists, anthropologists and ethnographers as detectives trying to answer the five basic questions of any good whodunit.

What:

Linea Sundstrom, an archaeologist with the University of Wisconsin, prepared a report on stone figures for the South Dakota State Historical Society in 2006. She catalogued 128 effigy and stone alignments across the state, including all that have been reported in the past, even if their current location and status are unknown. That does not include the dozens of stone arrangements that are tipi rings, historic foundations of buildings, cairns or mounds.

Those effigies often take on recognizable shapes: snakes, turtles, birds, fish, horses, rabbits, and humans. Then there a handful of medicine wheels – alignments with spoke-like lines radiating from a central point - and geometric forms whose meanings are no longer apparent.

Ian Brace, the former curator of archaeology and aboriginal studies at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina, Canada, did his master’s thesis on the stone effigies of Saskatchewan. In his estimation there are between 500 and 600 effigies spread throughout the northern Great Plains. It’s possible those effigies represent only a fraction of what existed before many were destroyed to make way for modern agriculture, he said.

In his thesis, which was published as the book “Boulder Monuments of Saskatchewan,” Brace said the boulders making up the effigies he studied were mostly bread loaf-sized and elliptical, rectangular, cuboid or triangular in shape. The stones are mainly granite and quartzite, which could be found plentifully on the Great Plains.

Sundstrom’s report said generally the rocks used in effigies along the Missouri River and in eastern South Dakota were from glacial tills, while sandstone is more frequent in the West River boulder effigies.

Where:

Brace said the figures are spread across the short-grass northern Plains, from central Nebraska up into Saskatchewan and from the Rockies into Minnesota and parts of Iowa, with some in Ontario and Ohio.

What Brace found interesting is, in Saskatchewan at least, the figures were never on the highest points of land, but on the secondary rises.

“So if you were traversing the countryside and were looking for a particular feature, whether it be a method of obtaining game or water, you would look on the secondary height of land and there would be a number of figures,” he said.

Among the effigies, turtles are common. There are half a dozen in Canada and Brace said the most southern effigy he knows of was a turtle figure in central Nebraska. South Dakota is home to 12 turtle forms, mostly in the central Missouri River region, but with some in the northwestern and eastern fringes of the state.

Two of three recorded thunderbird effigies are found in central South Dakota, according to Sundstrom.

The snake effigies in South Dakota are six of only seven known in the northern plains. Five of them - including one at Medicine Knoll near Blunt – are along the Missouri River between Okobojo Creek and Big Bend. The sixth effigy is along the James River while the last is in North Dakota near the town of Independence.

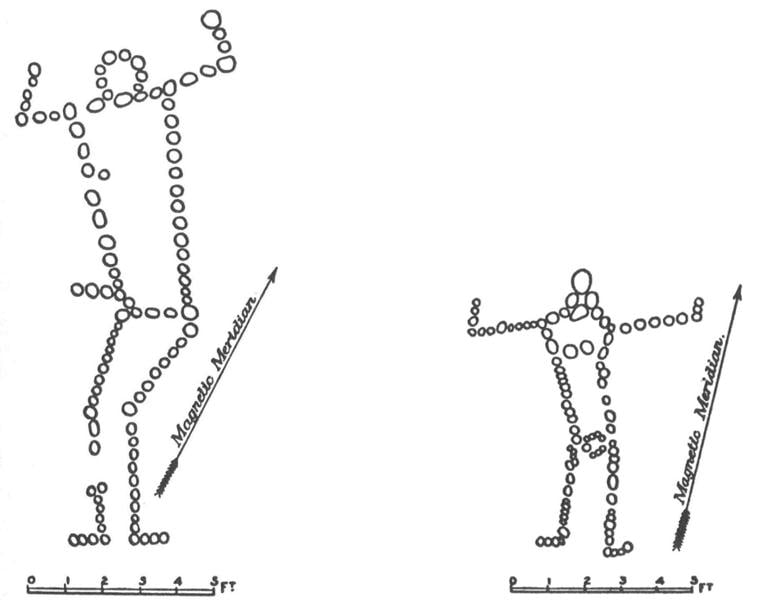

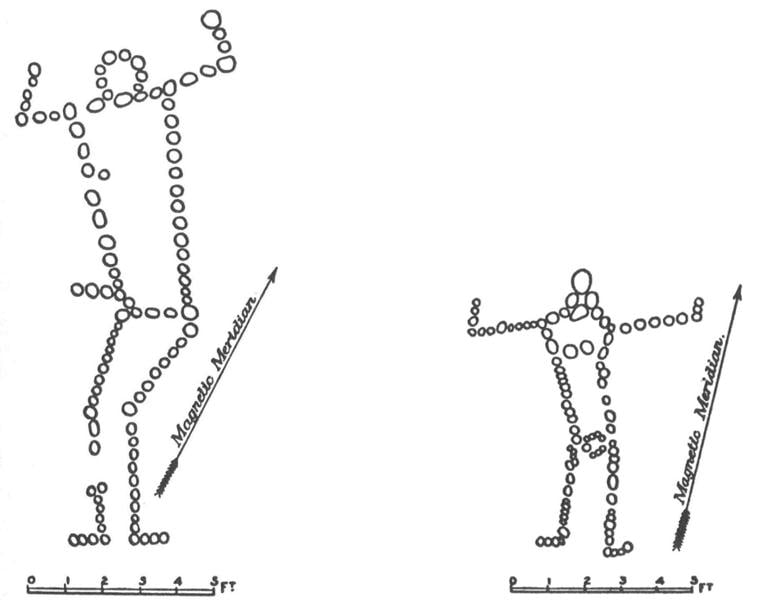

According to Sundstrom, human figures are rare in South Dakota, but occur much more frequently in Montana, North Dakota and Canada. The most prominent example of human figures in the state was probably Punished Woman Butte in Codington County, which was completely destroyed by 1914. The site had two figures outlined in stone, a man and a woman, depicted as lying on the ground with outstretched arms.

Local oral history gives the spot its name, with a story that could have been torn from the pages of a pulp detective novel. Though there are various accounts, the basic narrative is a woman ran away from the husband she was forced to marry to be with the man she loved. The jealous husband tracked the pair down and brutally murdered them on the spot. Some versions of the tale have the husband then being struck by lightning. The effigy was either a monument to the pair or a marker of their death and shame.

When:

The question of when these effigies were built is where the real detective work begins for archaeologists. The constructions are old, but answering exactly how old is nearly impossible.

Sundstrom says an argument can be made that some have existed at least a millennium. Their imagery – turtles, snakes and thunderbirds – is similar to that of the mound building civilizations to the east, which are generally dated to between A.D. 700 and 1100.

However, other effigies are part of the oral traditions of the Dakota and Nakota people, who claim to have built them. That would make them no older than A.D. 1600.

In the case of Punished Woman Butte, the Dakota told French mapmaker Joseph Nicollet in the 1830s that the hill was where the Sioux had once cruelly punished an adulteress. Sundstrom notes the event is mentioned in the Yanktonai winter count for 1784, which gives the year the name of “winyan wan pabaksapi,” or “when the woman was beheaded.”

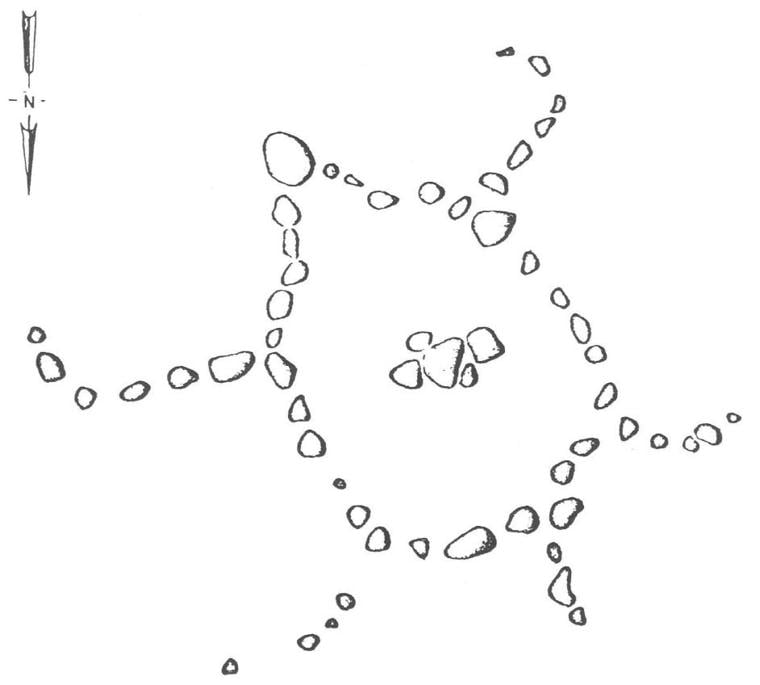

The oral history surrounding the well-preserved turtle effigy on Snake Butte in Hughes County says it’s where an Arikara warrior was fatally wounded while trying to warn his people of a hostile band of Sioux. Sundstrom says the conflict between those two peoples is first recorded in the Dakota winter count for 1694, meaning that effigy must have been built at a relatively late date.

Adrien Hannus, a professor of anthropology at Augustana College in Sioux Falls, said ultimately the problem with determining an age for the figures is there is nothing to date. Radiocarbon dating only works with organic matter, so that method is useless without fire pits or other signs of human activity nearby.

Sometimes studying petroglyphs – or rock engravings – that have similar designs and are often accompanied by fire pits can yield clues, he said.

An indicator of age may be the how much dirt has built up around the individual stones. However, Sundstrom says local erosion and buildup factors, plus climatic events such as the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, makes soil deposition an unreliable indicator.

Brace attempted to date figures using the lichens growing on the stones, but the method ran into numerous problems. Sulfuric gas from oil drilling or high amounts of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide killed lichens for miles around. Getting a baseline for growth was also problematic if there was no cemetery nearby with undisturbed lichen-covered headstones.

Based on what little evidence there is, the earliest alignments were probably made 2,000 years ago, Brace said.

That agrees with the opinion of South Dakota Assistant State Archaeologist Michael Fosha, who said he believes the effigies were made in the last 2,000 years and he’s even more confident that they are from the last 500 years. Many probably date from the 1700s, before European colonization of the plains, he said.

Who:

Because dating the effigies is nearly impossible, answering the question of who was around to build them is an equally perplexing task. The list of suspects is long and a combination of any of them could be responsible.

Brace said the question of who depends a lot on when a particular group was in a particular area. The Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Cree, and other Siouan peoples all moved across the Plains. Some of the alignments could be the work of a civilization that preceded all of them, he said.

He has visited effigy sites with different Canadian tribes, only to find the figures are not part of their oral traditions.

“Some of the features I can loosely attribute to one tribe or another, but I can’t assign all of them to any one particular tribe or some to one tribe or some to another,” Brace said.

Fosha said in his opinion the Cheyenne are a good contender because they crossed the Minnesota River and moved West across the plains hunting buffalo. The Arapaho are another good candidate, if the effigies can be attributed to any named language-speaking people, he said.

If some of the effigies are around 2,000 years old, then perhaps a group known as the Avonlea complex was their builder. Complex in this case is an archaeological term to describe a shared way of living. And the Avonlea have the same distribution as the effigies, running from Minnesota westward and up into Canada, Fosha said.

Sundstrom says the few recorded medicine wheels found in South Dakota, in Hand and Custer counties with another said to have been in Corson County, can be identified with Algonkian-speaking peoples, such as the Blackfoot, Cheyenne and Arapaho.

More than sixty such medicine wheels from those tribes can be found in Canada, Montana and North Dakota. The scarcity of similar features in South Dakota is not surprising as the Cheyenne and Arapaho only lived in the state for a few centuries, she said.

Northern Cheyenne oral tradition also includes references to an old village near Freeman, South Dakota, and a swan effigy found there. The effigy is said to honor a leader named Swan whose band moved across the Missouri River heading toward the Black Hills. The effigy’s head points west, indicating the direction of their travel, the tradition says.

Hannus, among others, said there wasn’t one single group of effigy builders. The practice could have been common among various Plains tribes.

“I think it would be very reckless to suggest that it was any single group or time period,” he said. “I think it’s absolutely spread across potentially thousands of years of time between the creation of one set of images and the creation of another set.”

Unfortunately for archaeological detectives, this particular question also has its fair share of red herrings. Since the arrival of white settlers, children, landowners and scout troops have built their own alignments in imitation of the ones already on the land.

Fosha related how he once became excited about a complex pattern he found in Harding County until the landowner pointed out it was a map of South Dakota that he and others made years ago as children.

Why:

But the most daunting question, because it encompasses aspects of all the others combined, is that of motive. Why draw large images with stone across the prairie landscape?

Sundstrom’s report lists several possible interpretations for the sites including memorials to important people or events, identifiers of particular social groups, shrines related to war, hunting and planting, and astronomical observatories.

“None of these are mutually exclusive and none have been decisively studied archaeologically,” her report says.

Brace takes a practical point of view, saying that many of the animal effigies were environmental indicators, acting as landmarks or identifying the location of resources.

For example, an effigy in Mankota depicts a salamander with a simple set of external gills, like one that lives in fresh water. The forms sits in an area with much alkaline water, but a line drawn from the tail through the head of the effigy pointed to one of the few fresh water springs, he said.

Brace sees a similar use for a buffalo effigy. A line drawn from the tail through the head leads to a blind coulee where large game could be driven off the edge.

The turtle effigies could mean that an important food source could be found in the area, he said.

For others, however, the figures seem to point to something more symbolic.

During an interview with the Capital Journal, Sundstrom said in Siouan symbology the turtle represents the earth, the snake is associated with water, and the thunderbird is the symbol for the air.

“The thing about the turtles and snakes is they were connected to bigger ideas, they could be used as metaphor,” she said.

Sundstrom’s report says many tribes, such as the Hidatsa, Lakota and the Omahas, use the symbol of the turtle to drive away rain and fog and or ask for luck in hunting.

Paul Picha, chief archaeologist for the State Historical Society of North Dakota, said among a number of groups, including the Mandan and Hidatsa, turtle effigies are mentioned in the ethnographic record.

“The turtle is associated with some aspects of Hidatsa and Mandan hunting territory and attracting bison to a location,” he said.

Hannus said there are a number of groups where the turtle is a ritualistically important symbol.

“I think it’s seen as a life-giving source and in some of the groups the turtle is the creature that is seen to have formed the landscape on which people lived. In other words by bringing up mud from under the water and actually creating land surfaces. So it’s certainly an important image of people here in the Dakotas and people well to the east and probably to the west as well,” he said.

Sundstrom also advances the theory that the state’s snake effigies are shrines to corn growing. Central South Dakota was home to the Arikara, who were known to their neighbors as the Corn Eater tribe. And Lakota tradition says the Big Bend area of the Missouri River is the birthplace of corn horticulture, her report said.

In certain mythologies, agriculture is represented by Old Woman Who Never Dies who is said to have a snake husband. And snakes, which disappear in the winter and come back in the spring, are associated with the return of corn spirits, she said.

For the human figures, many probably represent the mythical Blackfoot trickster hero Napi, Sundstrom’s report says.

Other human figures may be commemorative. In Saskatchewan, Brace said there is a figure of a woman with eyes, but no nose or mouth like other effigies. With no oral tradition connected with it, Brace’s interpretation is it could be tied to a story similar to Punished Woman Butte.

A punishment for adultery was to cut off a woman’s nose and upper lip, which would explain the effigy’s lack of facial features, he said.

And there are many more alignments and figures which are obviously man-made, but have no observable pattern or context for modern day archaeologists, he said.

An Enduring Mystery:

With so many questions and so few clues, the enigma of the stone effigies may be a mystery that will never be entirely solved.

Archaeologists, such as Hannus, are hesitant to talk in specifics and quick to say their answers are only guesswork and opinion.

“It’s something that becomes speculative and, of course, most of us like to think of ourselves as scientists and we don’t want to wander into the realm of speculation,” he said.

Sundstrom said one major issue in understanding the effigies, even the ones with oral traditions, is the natural disconnect inherent in translating ideas between two cultures. With the older effigies, it’s possible the connection with the past and the effigies’ purposes is already lost.

“As with a lot of archaeology we have to say ‘I don’t know, but this is as far as the data takes me,’” she said.

TOPICS: History

KEYWORDS: americaunearthed; ancientnavigation; barryfell; effigy; epigraphyandlanguage; godsgravesglyphs; kensingtonrunestone; olofohman; scottwolter; stone

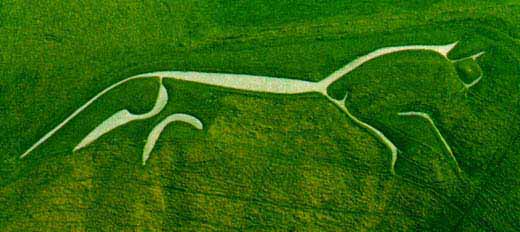

Courtesy of the South Dakota State Historical Society

Snake Effigy

In this 1997 photo, Royal Runge, the rancher who formerly owned the Medicine Knoll site from 1938 until 1999 and took care to preserve it, is shown here alongside the snake mosaic made of stones that archaeologists believe is close to 500 years old.

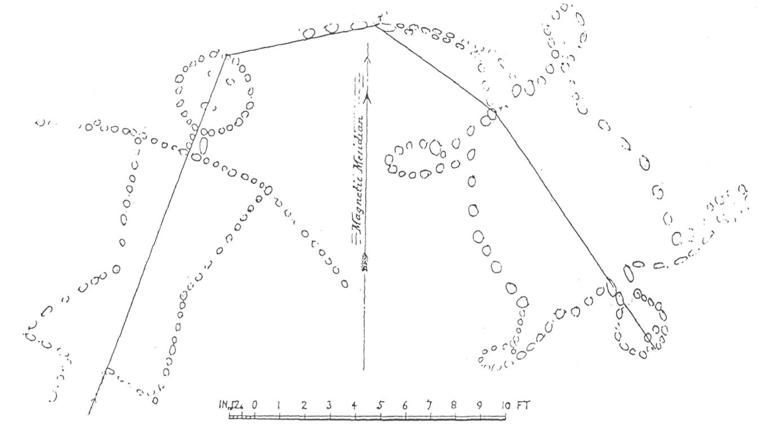

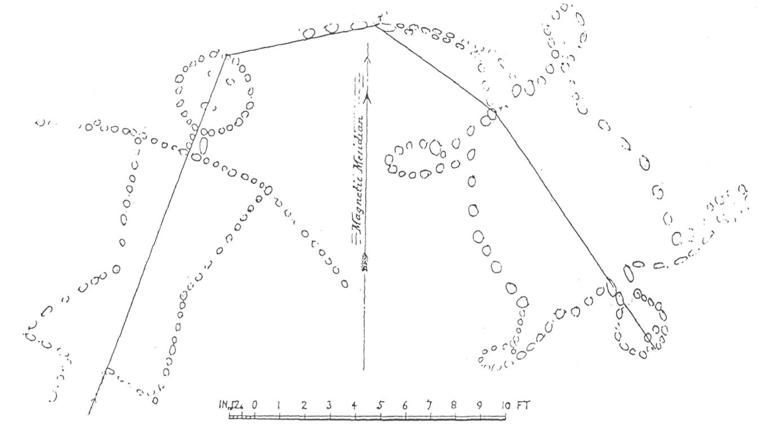

Image courtesy of Linea Sundstrom

Jerauld County effigy

1890 sketch by archaeologist T.H. Lewis of human and turtle effigies in Jerauld County. The human effigy was gone by 1982 and local tradition says the turtle was reconstructed by a troop of Boy Scouts in the 1930s.

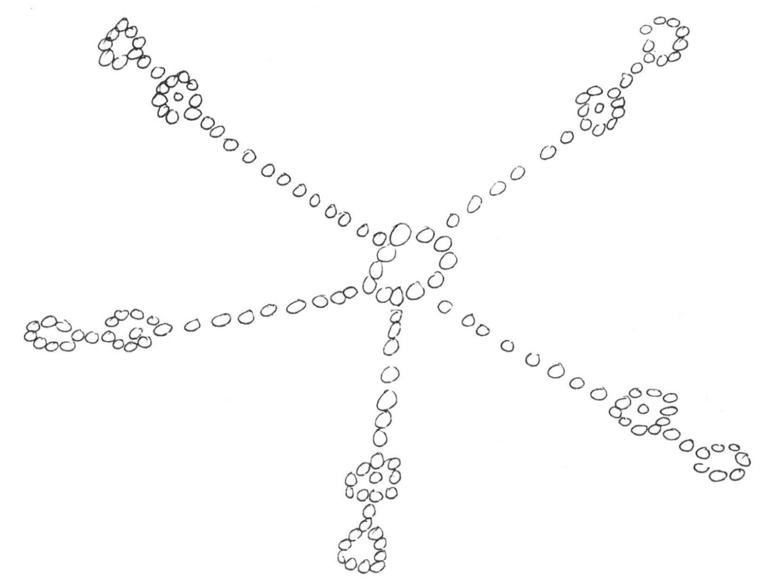

Image courtesy of Linea Sundstrom

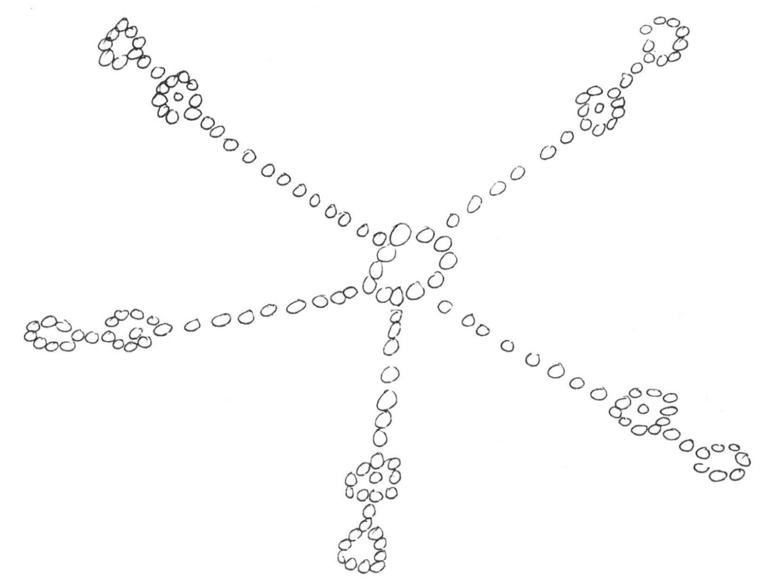

Medicine Wheel

Medicine wheel reported in Custer County in 1949, but the exact location is unknown.

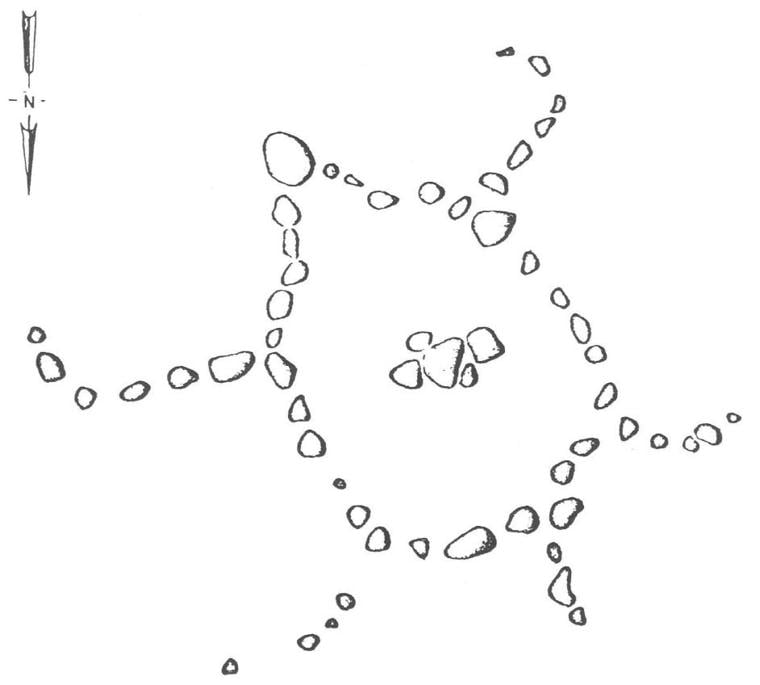

Image courtesy of Linea Sundstrom

Turtle effigy

Turtle effigy on Snake Butte in Hughes County. Oral history says the figure commemorates an Arikara warrior who was fatally wounded by a hostile band of Sioux, but managed to go nearly a mile in an attempt to warn his people.

Image courtesy of Linea Sundstrom

Punished Woman Butte

Scale drawings of male and female figure that were part of an effigy on Punished Woman Butte in Codington County. Oral history said the figures represent lovers who were killed on the spot by a jealous husband.

Image courtesy of Linea Sundstrom

Swan Effigy

Photo of an unidentified man kneeling alongside the swan effigy near Freeman. The picture ran in the June 1964 edition of “Wi-Iyohi,” the bulletin of the South Dakota State Historical Society.

1

posted on

09/02/2014 10:25:42 AM PDT

by

Theoria

To: SunkenCiv

ping, cool.

ping, ouch, not cool

'In the case of Punished Woman Butte, the Dakota told French mapmaker Joseph Nicollet in the 1830s that the hill was where the Sioux had once cruelly punished an adulteress. Sundstrom notes the event is mentioned in the Yanktonai winter count for 1784, which gives the year the name of “winyan wan pabaksapi,” or “when the woman was beheaded.”'

2

posted on

09/02/2014 10:26:23 AM PDT

by

Theoria

(I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive)

To: Theoria

There are earthworks and stone works all over the planet. They used what was available. They probably also used wood where it was abundant.

3

posted on

09/02/2014 10:34:57 AM PDT

by

cripplecreek

("Moderates" are lying manipulative bottom feeding scum.)

To: Theoria

Indian cliff paintings on the Mohawk River

“It was on the same shore, just east of the city, that the limestone

escarpment cited in the journal, itself a noteworthy feature of the riverside terrain, was observed. Although the Frenchmen

made no mention of seeing images on these rocks, another, passing

by a few months earlier, describes them:

This day we passed a rock projecting out of the bank

of the river, whereon was painted, with great ingenuity, in

red colours, a canoe with the representation of seven men

in it, which is said to be done annually by Indians, coming

several hundred miles for that purpose, in order to commemorate

the slaughter of seven Indians, who went off

from that neighborhood in some former wars, and were all

destroyed.

Jacob Lindley, 1793 16

As late as 1810, when DeWitt Clinton journeyed along this

waterway and recorded his observations, the images were still

visible:

About sixteen miles from Schenectady, we saw, on

the left bank of the river, a curious specimen of Indian

painting. On an elevated rock was painted a canoe, with

seven warriors in it, to signify that they were proceeding on

a war expedition. This was executed with red ochre, and

has been there for upwards of half a century.

DeWitt Clinton, 1810 17

Paintings of this type on rock were no doubt frequently made

by Native Americans since prehistoric times, but few could survive

more than a few years before they weathered away. Some

claimed the figures were “retouched,” which prolonged their life.

Others suggested a connection between these paintings and the

river boat traffic of the 1790s and early 1800s:

The Flat boatmen of the Mohawk held these rocks in

such reverence that they at times refreshed the paintings.

LaGrand Strang, 1887 18

That the images recalled so clearly in the early nineteenth century

were the product of various acts of “refreshing” is suggested

by the account of a visit to the site in 1796:

Stopped by the way at Miles’s (formerly Guy

Johnson’s house); there met a Dr. Sweet, who fell into conversation,

and offered to conduct us to the painted rock,

which he said was about two miles down the river. Took

him up in the carriage and rode with him two miles. Then

he and I left the carriage to search for the rock. This ramble

took up forty minutes, and I walked about two miles,

partly through woods and partly through fields.

The rock is on the north bank of the Mohawk, fifteen

miles above Skenectada. It is a perpendicular ledge of

limestone, with a pretty smooth surface and about twenty

feet high. On the upper part - which is easily accessible, the

laminae projecting in various places - appear the remains

of some red paint, which has been in the same situation for

eighteen or twenty years. Imagination may conceive the

paint to resemble almost any thing; but judgement cannot

decide without the help of testimony.

The tradition is that it was painted by the Indians in

memory of some canoes of Indians who went thence to

war, and never returned; that the painting represented

canoes and men in them; and that this painting is frequently

renewed to preserve the memory of the event. Some add

that the renewal is performed in the night, or by some

invisible hand. The fact is that there is a rock with some

appearance of red paint, that the paint has been in some

measure defended from the weather by a projection of the

rock over it, and that the place is easily accessible by similar

projections under it. This is all that can be said with

any certainty.

As to the frequent renewal of the paint, &c., I was

assured by Dr. Sweet that he had known it to be in the same

condition as we saw it for eighteen years past; and a man

whom we took as a pilot, who appeared to be abou

t twenty-

five years old, said it always looked just so since his

remembrance.

Jeremy Belknap, 1796 23

ibid p12-13

The drawings above, created one hundred years ago by Rufus Grider, have preserved for us an image of what the

Native American pictograph known as “Painted Rocks” must have looked like to passing boatmen. He based his

reconstruction on eyewitness interviews. At that time a number of persons could still recall the site in detail, and

related to him their recollections:

“Within the remembrance, possibly of some person still living, there was a large rock on the north shore

of the Mohawk, near Amsterdam, to be seen at low watermark, that contained Indian Memorials, such as the

figures of men and animals, and supposed by some to have been traced with red chalk, although they may have

been in vermilion, which the Whites bartered with the Natives for peltry.”

Jeptha Simms, 1882 19

“The rocks contained 12 or 15 Indians, with two canoes, two Indians in each canoe, one at the bow the

other at the stern, going west, other Indians on foot. A duck flying above eastward.”

John Winnie, 1887 20

“I lived all my life in the vicinity of the rocks. I lived on the south bank of the river when the canal was

made. Our house was just opposite the rocks and was the first house built [in] the present Port Jackson, and

is still standing. There were figures on the rocks, at least 9 in number, they were painted with red colors. My

grandfather was a soldier in the Revolutionary Army. He, when passing the rocks in a boat, was shot at by an

Indian who lay in ambush and wounded him. It was covered with pines and undergrowth.”

David DeForest, 1887 21

“I was born in Amsterdam in the year 1826 and lived there until I was 21 years old. I remember well the

painted rocks. I was very fond of being on the water; and before I was 14 years old I and another boy named

Abm. Pulling (now deceased) became owners of a rowboat, and in it passed many hours on the river, and

rowed past the painted rocks more times than I can remember. There were two canoes going upstream, as if

racing, with two Indians in each canoe. There were 10 or 12 Indians on the bank who were walking westward

and apparently watching the canoe race. The work was done in red paint, the figures were about 4 feet high,

and could be plainly seen from the opposite side of the river.

“... The pictures at that time had the appearance of being retouched, probably to perpetuate them. I think

they are now entirely obliterated. They were on the perpendicular face of the rocks which overlook the river, a

little east of the freight house and directly south of the Murphy Bros. warehouse. These tracings were of the

plainest and rudest kind.”

Moses T. Kehoo, 1887 22 ibid p13

4

posted on

09/02/2014 10:37:55 AM PDT

by

bunkerhill7

("The Second Amendment has no limits on firepower"-NY State Senator Kathleen A. Marchione.")

To: Theoria

There is more than ample evidence that European and Asian people were here long long before Christoforo or the Vikings. Here in AZ for example there is a grave of an Englishman that has been dated two hundred years earlier than the Vikings. How they got here and what they were looking for is not known. Maybe came for free medical and food stamps.

5

posted on

09/02/2014 10:39:55 AM PDT

by

Don Corleone

("Oil the gun..eat the cannoli. Take it to the Mattress.")

To: Theoria

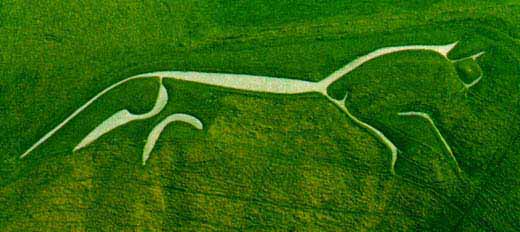

There are hundreds of these figures all over England. Some are centuries old.

6

posted on

09/02/2014 10:42:16 AM PDT

by

AnAmericanMother

(Ecce Crucem Domini, fugite partes adversae. Vicit Leo de Tribu Iuda, Radix David, Alleluia!)

To: Don Corleone

He was trying to get home but wouldn’t ask anyone for directions.

7

posted on

09/02/2014 10:42:35 AM PDT

by

Hieronymus

( (It is terrible to contemplate how few politicians are hanged. --G.K. Chesterton))

To: AnAmericanMother

Illegal aliens? Space aliens that is.

8

posted on

09/02/2014 10:46:12 AM PDT

by

rktman

(Ethnicity: Nascarian. Race: Daytonafivehundrian)

To: Don Corleone

I think there were probably lots of visitors to this hemisphere.

In Peru there is a tribe that appears to have Asian ancestry (post land bridge). Their traditional pottery style is nearly identical to a Japanese tribe and they suffer a disease found no where else than the Ainu of northern Japan.

9

posted on

09/02/2014 10:48:42 AM PDT

by

cripplecreek

("Moderates" are lying manipulative bottom feeding scum.)

To: Don Corleone

10

posted on

09/02/2014 10:54:05 AM PDT

by

Salamander

(People will stare. Might as well make it worth their while.)

To: Theoria

I wonder how they figure they are 500 years or so.

Interesting thread.

11

posted on

09/02/2014 10:59:03 AM PDT

by

Beowulf9

To: Theoria

Just curious, but I wonder if any of the ‘wizards of smart’ thought about asking the Indians about the images.

Another thought. Anyone ask Giorgio?

12

posted on

09/02/2014 11:01:52 AM PDT

by

Tupelo

(I am feeling more like Phillip Nolan by the day.)

To: Theoria

Just curious, but I wonder if any of the ‘wizards of smart’ thought about asking the Indians about the images.

Another thought. Anyone ask Giorgio?

13

posted on

09/02/2014 11:01:53 AM PDT

by

Tupelo

(I am feeling more like Phillip Nolan by the day.)

To: rktman

Nope, just a creative bunch of folks with lots of time on their hands and materials available (in the case of most of Sussex, lovely green turf with bright white chalk right underneath).

My personal favorite (not really safe for work) with editorial comment by Homer Simpson:

Homer chalk giant angers pagans

Anything that "angers pagans" is probably a good idea.

14

posted on

09/02/2014 11:02:44 AM PDT

by

AnAmericanMother

(Ecce Crucem Domini, fugite partes adversae. Vicit Leo de Tribu Iuda, Radix David, Alleluia!)

To: cripplecreek

Latest word (acc. to Smithsonian Magazine) is that Kennewick’s Man’s closest relatives are probably the Ainu.

15

posted on

09/02/2014 11:03:51 AM PDT

by

AnAmericanMother

(Ecce Crucem Domini, fugite partes adversae. Vicit Leo de Tribu Iuda, Radix David, Alleluia!)

To: Theoria

Why draw large images with stone across the prairie landscape?

16

posted on

09/02/2014 11:26:45 AM PDT

by

BenLurkin

(This is not a stBut is it grammatically catement of fact. It is either opinion or satire; or both.)

To: Theoria

17

posted on

09/02/2014 2:03:02 PM PDT

by

Oratam

To: Theoria; StayAt HomeMother; Ernest_at_the_Beach; decimon; 1010RD; 21twelve; 24Karet; ...

Thanks Theoria.

18

posted on

09/18/2014 7:54:42 PM PDT

by

SunkenCiv

(https://secure.freerepublic.com/donate/)

To: bunkerhill7

Formatting is your friend. Took me less than ten seconds.

Indian cliff paintings on the Mohawk River

“It was on the same shore, just east of the city, that the limestone escarpment cited in the journal, itself a noteworthy feature of the riverside terrain, was observed. Although the Frenchmen made no mention of seeing images on these rocks, another, passing by a few months earlier, describes them:

This day we passed a rock projecting out of the bank of the river, whereon was painted, with great ingenuity, in red colours, a canoe with the representation of seven men in it, which is said to be done annually by Indians, coming several hundred miles for that purpose, in order to commemorate the slaughter of seven Indians, who went off from that neighborhood in some former wars, and were all destroyed.

Jacob Lindley, 1793 16 As late as 1810, when DeWitt Clinton journeyed along this waterway and recorded his observations, the images were still visible:

About sixteen miles from Schenectady, we saw, on the left bank of the river, a curious specimen of Indian painting. On an elevated rock was painted a canoe, with seven warriors in it, to signify that they were proceeding on a war expedition. This was executed with red ochre, and has been there for upwards of half a century.

DeWitt Clinton, 1810 17 Paintings of this type on rock were no doubt frequently made by Native Americans since prehistoric times, but few could survive more than a few years before they weathered away. Some claimed the figures were “retouched,” which prolonged their life.

Others suggested a connection between these paintings and the river boat traffic of the 1790s and early 1800s:

The Flat boatmen of the Mohawk held these rocks in such reverence that they at times refreshed the paintings.

LaGrand Strang, 1887 18 That the images recalled so clearly in the early nineteenth century were the product of various acts of “refreshing” is suggested by the account of a visit to the site in 1796:

Stopped by the way at Miles’s (formerly Guy Johnson’s house); there met a Dr. Sweet, who fell into conversation, and offered to conduct us to the painted rock, which he said was about two miles down the river. Took him up in the carriage and rode with him two miles. Then he and I left the carriage to search for the rock. This ramble took up forty minutes, and I walked about two miles, partly through woods and partly through fields.

The rock is on the north bank of the Mohawk, fifteen miles above Skenectada. It is a perpendicular ledge of limestone, with a pretty smooth surface and about twenty feet high. On the upper part - which is easily accessible, the laminae projecting in various places - appear the remains of some red paint, which has been in the same situation for eighteen or twenty years. Imagination may conceive the paint to resemble almost any thing; but judgement cannot decide without the help of testimony.

The tradition is that it was painted by the Indians in memory of some canoes of Indians who went thence to war, and never returned; that the painting represented canoes and men in them; and that this painting is frequently renewed to preserve the memory of the event. Some add that the renewal is performed in the night, or by some invisible hand. The fact is that there is a rock with some appearance of red paint, that the paint has been in some measure defended from the weather by a projection of the rock over it, and that the place is easily accessible by similar projections under it. This is all that can be said with any certainty.

As to the frequent renewal of the paint, &c., I was assured by Dr. Sweet that he had known it to be in the same condition as we saw it for eighteen years past; and a man whom we took as a pilot, who appeared to be abou t twenty- five years old, said it always looked just so since his remembrance.

Jeremy Belknap, 1796 23 ibid p12-13

The drawings above, created one hundred years ago by Rufus Grider, have preserved for us an image of what the Native American pictograph known as “Painted Rocks” must have looked like to passing boatmen. He based his reconstruction on eyewitness interviews. At that time a number of persons could still recall the site in detail, and related to him their recollections:

“Within the remembrance, possibly of some person still living, there was a large rock on the north shore of the Mohawk, near Amsterdam, to be seen at low watermark, that contained Indian Memorials, such as the figures of men and animals, and supposed by some to have been traced with red chalk, although they may have been in vermilion, which the Whites bartered with the Natives for peltry.”

Jeptha Simms, 1882 19

“The rocks contained 12 or 15 Indians, with two canoes, two Indians in each canoe, one at the bow the other at the stern, going west, other Indians on foot. A duck flying above eastward.”

John Winnie, 1887 20

“I lived all my life in the vicinity of the rocks. I lived on the south bank of the river when the canal was made. Our house was just opposite the rocks and was the first house built [in] the present Port Jackson, and is still standing. There were figures on the rocks, at least 9 in number, they were painted with red colors. My grandfather was a soldier in the Revolutionary Army. He, when passing the rocks in a boat, was shot at by an Indian who lay in ambush and wounded him. It was covered with pines and undergrowth.”

David DeForest, 1887 21

“I was born in Amsterdam in the year 1826 and lived there until I was 21 years old. I remember well the painted rocks. I was very fond of being on the water; and before I was 14 years old I and another boy named Abm. Pulling (now deceased) became owners of a rowboat, and in it passed many hours on the river, and rowed past the painted rocks more times than I can remember. There were two canoes going upstream, as if racing, with two Indians in each canoe. There were 10 or 12 Indians on the bank who were walking westward and apparently watching the canoe race. The work was done in red paint, the figures were about 4 feet high, and could be plainly seen from the opposite side of the river.

“... The pictures at that time had the appearance of being retouched, probably to perpetuate them. I think they are now entirely obliterated. They were on the perpendicular face of the rocks which overlook the river, a little east of the freight house and directly south of the Murphy Bros. warehouse. These tracings were of the plainest and rudest kind.”

Moses T. Kehoo, 1887 22 ibid p13

19

posted on

09/19/2014 12:36:00 PM PDT

by

dsc

(Any attempt to move a government to the left is a crime against humanity.)

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson