Posted on 12/22/2013 1:39:29 PM PST by lbryce

Rapatronic Nuclear Photographs-Images Taken Within 10 Nano-Seconds of Nuclear Detonation

Click Here:The Camera That Captured the First Millisecond of a Nuclear Bomb Blast

From Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

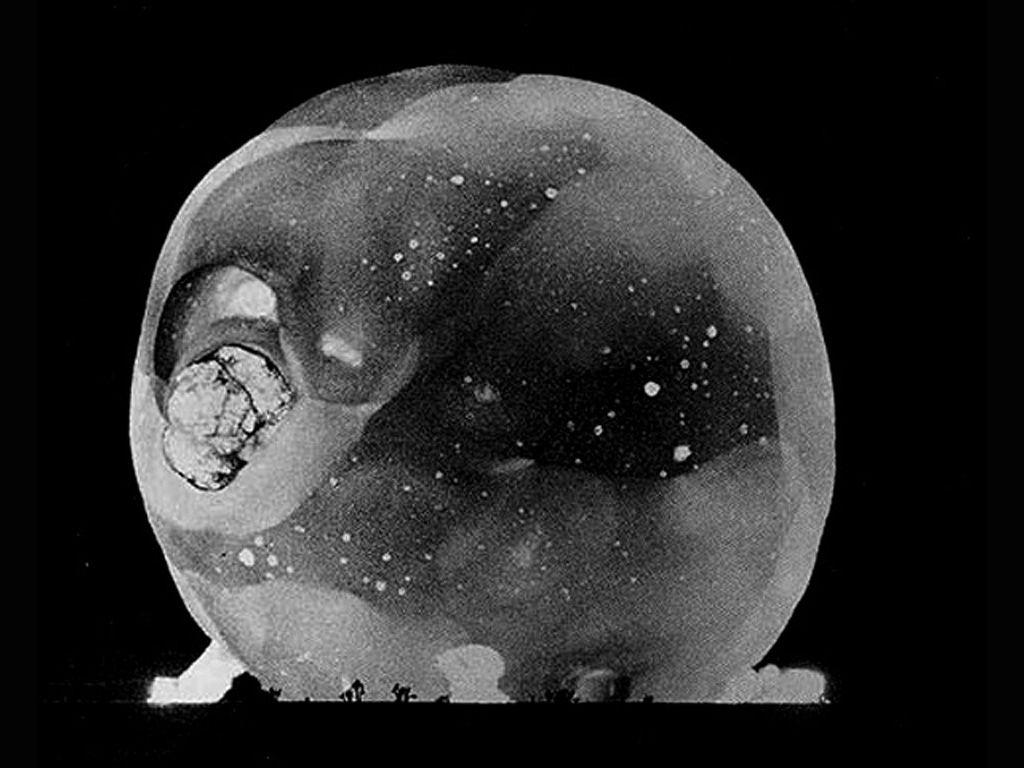

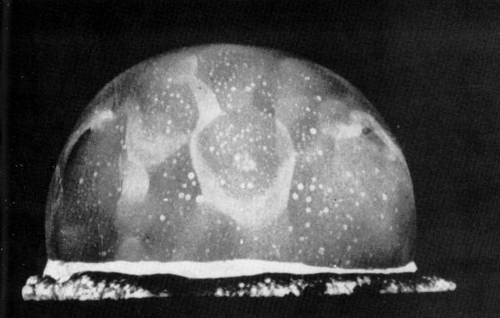

Nuclear explosion photographed by rapatronic camera less than 1 millisecond after detonation. From the Tumbler-Snapper test series in Nevada, 1952. The fireball is about 20 meters in diameter in this shot. The spikes at the bottom of the fireball are known as the rope trick effect.

The rapatronic camera (a contraction of rapid action electronic) is a high-speed camera capable of recording a still image with an exposure time as brief as 10 nanoseconds (100 million frames per second).

The camera was developed by Harold Edgerton in the 1940s and was first used to photograph the rapidly changing matter in nuclear explosions within milliseconds of ignition. To overcome the speed limitation of a conventional camera's mechanical shutter, the rapatronic camera uses two polarizing filters and a Faraday cell (or in some variants a Kerr cell). The two filters are mounted with their polarization angles at 90° to each other, to block all incoming light. The Faraday cell sits between the filters, which changes the polarization plane of light passing through it depending on the level of magnetic field applied, acts as a shutter when it is energized at the right time for a very short amount of time, allowing the film to be properly exposed.

In magneto-optical shutters, the active material of the Faraday cell (e.g. dense flint glass, which reacts well to strong magnetic field[2]) is located inside an electromagnet coil, formed by few loops of thick wire. The coil is powered through a pulse forming network, by a discharge of a high-voltage capacitor (e.g. 2 microfarads at 1000 volts), switched into the coil by a trigatron or a thyratron. In electro-optical shutters, the active material is a liquid, typically nitrobenzene, located in a cell between two electrodes. A brief impulse of high voltage is applied to rotate the polarization of the passing light.

For a film-like sequence of high-speed photographs, as used in the photography of nuclear and thermonuclear tests, arrays of up to 12 cameras were deployed, with each camera carefully timed to record a different time frame. Each camera was capable of recording only one exposure on a single sheet of film. Therefore, in order to create time-lapse sequences, banks of four to ten cameras were set up to take photos in rapid succession. The average exposure time used was three microseconds.

This links to the Web Page As Illustrated Below:Damn Interesting:Rapatronic Nuclear Photographs

CLIC HERE:Raptronic Photographs

16 seconds After Detonation

There is a wealth of information regarding rapatronic nuclear photographs that was much too overwhelming for me to post. For those who want to explore this subject, I suggest the following.

Step 1-Do a search for rapatronic nuclear photographs.

Step 2-Click on the photogrpah that interests you

Step 3-Visit the page the image is located.

How did they trigger the shutter at just the precise instant?

Have you found that in your reading?

The Kerr effect allows for very fast shutter speed but how is the time to trigger it controlled?

Some of the photos remind of viruses or diatoms.

Several of them are eerie looking, like some sort of giant parasite giving birth. Others look like skull x-rays of an unknown species of hominid, hence the image of human skulls mixed in.

Click Here:Ghost Story:Rapatronic Cameras Capture Nuclear Explosion At Instant Of Detonation

Way back in the 40s when the US was experimenting with atomic bombs there were many problems to overcome. One of which was studying fireball growth at the moment of detonation.

Although photographic technology was growing quickly, even the fastest cameras of the time could not handle the speed at which these fireballs expanded and typically ended up with blurred images at best.

These problems continued until Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton a professor from MIT invented the “rapatronic Camera“. So advanced were these cameras, they could capture motion one ten-millionth of a second after detonation and from seven miles away, no less. Exposure time was a mere ten nanoseconds to boot.

Amazingly a fireball could still grow to 100 feet in diameter at such an instant but the cameras were fast enough to enable vital research into one of the many mysteries of an atomic explosion.

It’s still a bit mind bending to many that we had such technology at that time, but humans have developed some technology without the help of space aliens.

Here’s more on this very interesting and groundbreaking photographic technology:

During the early days of atomic bomb experiments in the 1940s, nuclear weapons scientists had some difficulty studying the growth of nuclear fireballs in test detonations. These fireballs expanded so rapidly that even the best cameras of that time were unable to capture anything more than a blurry, over-exposed frame for the first several seconds of the explosion.

Before long a professor of electrical engineering from MIT named Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton invented the rapatronic camera, a device capable of capturing images from the fleeting instant directly following a nuclear explosion. These single-use cameras were able to snap a photo one ten-millionth of a second after detonation from about seven miles away, with an exposure time of as little as ten nanoseconds. At that instant, a typical fireball had already reached about 100 feet in diameter, with temperatures three times hotter than the surface of the sun.

Edgerton was a pioneer in high-speed photography, receiving a bronze medal from the Royal Photographic Society in 1934 for his work in strobe photography. He used the technique to photograph many events that typical cameras were much too slow to capture, such as the instant of a balloon bursting, and bullets impacting various materials. He developed the rapatronic camera about ten years later, for the specific purpose of photographing nuclear explosions for the government.

In a typical setup at a nuclear test site, a series of ten or so rapatronic cameras were necessary, because each was able to take only one photograph… no mechanical film advance system was anywhere neat fast enough to allow for a second photo. Another mechanical limitation which had to be overcome was the shutter mechanism. Mechanical shutters were incapable of moving quickly enough to capture the instant one ten-millionth of a second after detonation, so Edgerton’s ingenious cameras used a unique non-mechanical shutter which utilized the polarization of light.

As you’ve probably noticed, if one takes two pieces of polarized glass (such as the lenses from polarized sunglasses) and lays them atop one another at 90° angles, no light is able to pass through. This is because each one filters out light which is not polarized to its polarization axis, so the combination of the two lenses filters out 100% of the light. Edgerton ‘s rapatronic camera appears to have used this property in combination with a Kerr cell– a nifty and obscure optical element which rotates light’s plane of polarization when a high-voltage field is applied.

The rapatronic camera lens included two perpendicular polarizers, which prevented any light from entering… but sandwiched in between them was a Kerr cell. When the Kerr cell was energized, it affected all of the light which passed through the first polarizer by rotating its plane of polarization by 90°, realigning the light to match the second polarizer. This allowed the light to pass through both polarizers whenever the Kerr cell was provided with electricity, which is exactly what was done for 10 nanoseconds at the critical moment. This assembly provided an extremely fast non-mechanical shutter, exposing the film to the light for a minuscule fraction of time.

The resulting extraordinary photographs revealed intricate details of the first instant of an atomic explosion, including a few surprises such as irregular “mottling” caused primarily by variations in the density of the bomb’s casing. It also showed the detail of the “rope trick effect,” where the rapid vaporization of support cables caused curious lines to emanate from the bottom of an explosion. But even aside from the scientific utility of the images, they certainly show that these fantastically destructive nuclear fireballs have a hauntingly beautiful side, even if it only lasts for one ten-millionth of a second.

This is how the shutter works not when the electrical current is applied. How is the timing of the application of the current decided and how is it executed?

I read all this and more b4 asking.

As you’ve probably noticed, if one takes two pieces of polarized glass (such as the lenses from polarized sunglasses) and lays them atop one another at 90° angles, no light is able to pass through. This is because each one filters out light which is not polarized to its polarization axis, so the combination of the two lenses filters out 100% of the light. Edgerton ‘s rapatronic camera appears to have used this property in combination with a Kerr cell– a nifty and obscure optical element which rotates light’s plane of polarization when a high-voltage field is applied.

The rapatronic camera lens included two perpendicular polarizers, which prevented any light from entering… but sandwiched in between them was a Kerr cell. When the Kerr cell was energized, it affected all of the light which passed through the first polarizer by rotating its plane of polarization by 90°, realigning the light to match the second polarizer. This allowed the light to pass through both polarizers whenever the Kerr cell was provided with electricity, which is exactly what was done for 10 nanoseconds at the critical moment. This assembly provided an extremely fast non-mechanical shutter, exposing the film to the light for a minuscule fraction of time.

Oppenheimer speaking in a 1965 television broadcast about the moments following the Trinity test: “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty, and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

I suppose, if he had a patent on it, you could probably find the solution you’re seeking by going to the US Patent Offce web site.

Some were thinking about how the heck they were going to get this to Stalin.

“We’ll meet again....don’t know where....don’t know when.....”

Bizarre.

Truman was stymied for sure by Stalin’s nonchalant, practically apathetic reaction having made ambiguous reference to events at Trinity.

Whoa! Bump!

It's called trial and error.

Click Here:http://simplethinking.com/home/rapatronic_photographs.htm

All of these explosions were tests. With the exception of air dropped tests, the explosions were triggered electrically from a manned blockhouse, not from the bomb itself.

You simply trigger the cameras simultaneously with the explosion, plus the desired delay for each camera.

The cameras were not responding to the explosion of the bomb.

Yes these are eerie and fascinating.

From past research I recall that:

The spikey projections coming out from the bottom of many of the blasts are the explosive vaporization of the coating/galvanize of the tower guy-wires. The wires are visible in some of the photos.

Endless information here:

http://nuclearweaponarchive.org/

One possible way:

I know that optical fibers would be placed inside the nuke (or perhaps the explosive that initiates the nuke reaction). The light pulse would outrun the destruction of the fiber, and arrive at distant instrumentation.

No, the radiation wavefront of soft X-rays advances in front of the visible light (it is what vaporizes the tower guy wires creating the “spikes” in some of these photos). It would destroy the fiber cable before the visible light was transmitted. Radiation also darkens fibers, which leads to it being of limited use in long term radiation environments. Also atmospheric tests were ended well before practical fibers were developed.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.