Posted on 12/15/2010 5:25:50 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

News of the Week in Review

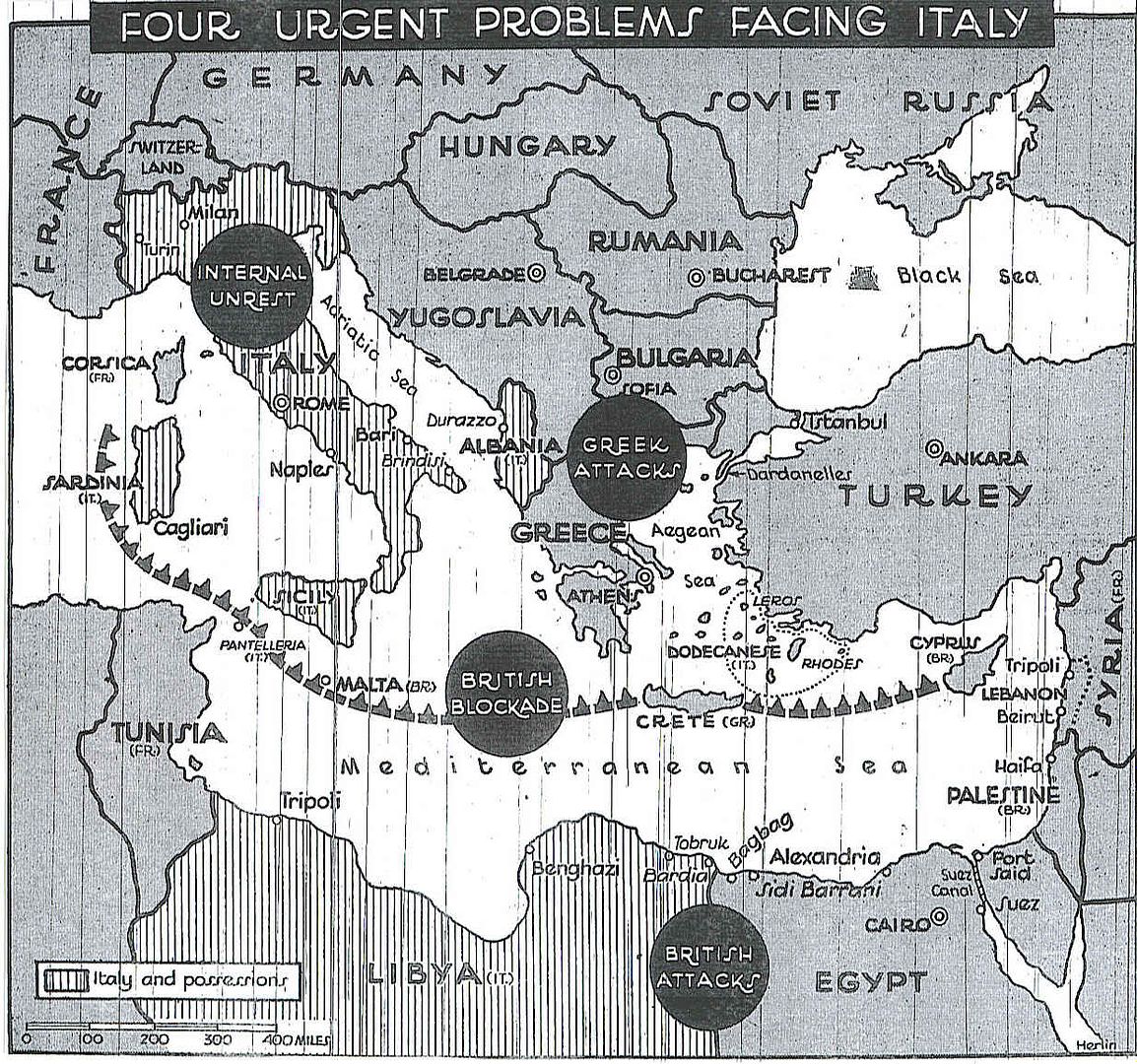

Four Urgent Problems Facing Italy (map) – 12

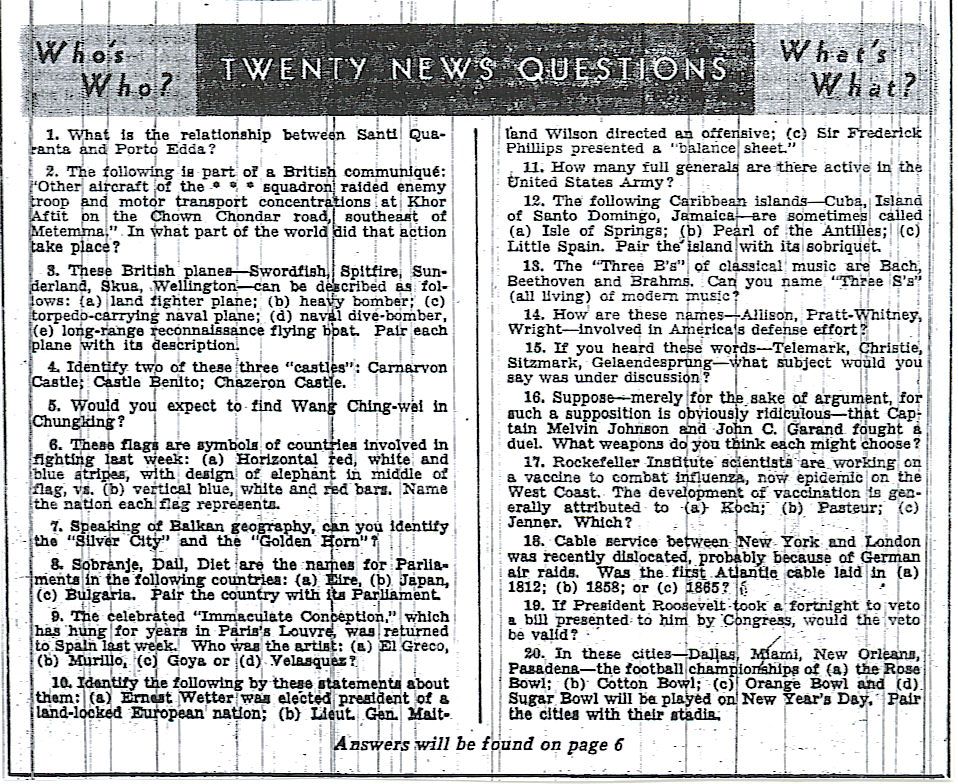

Twenty News Questions – 13

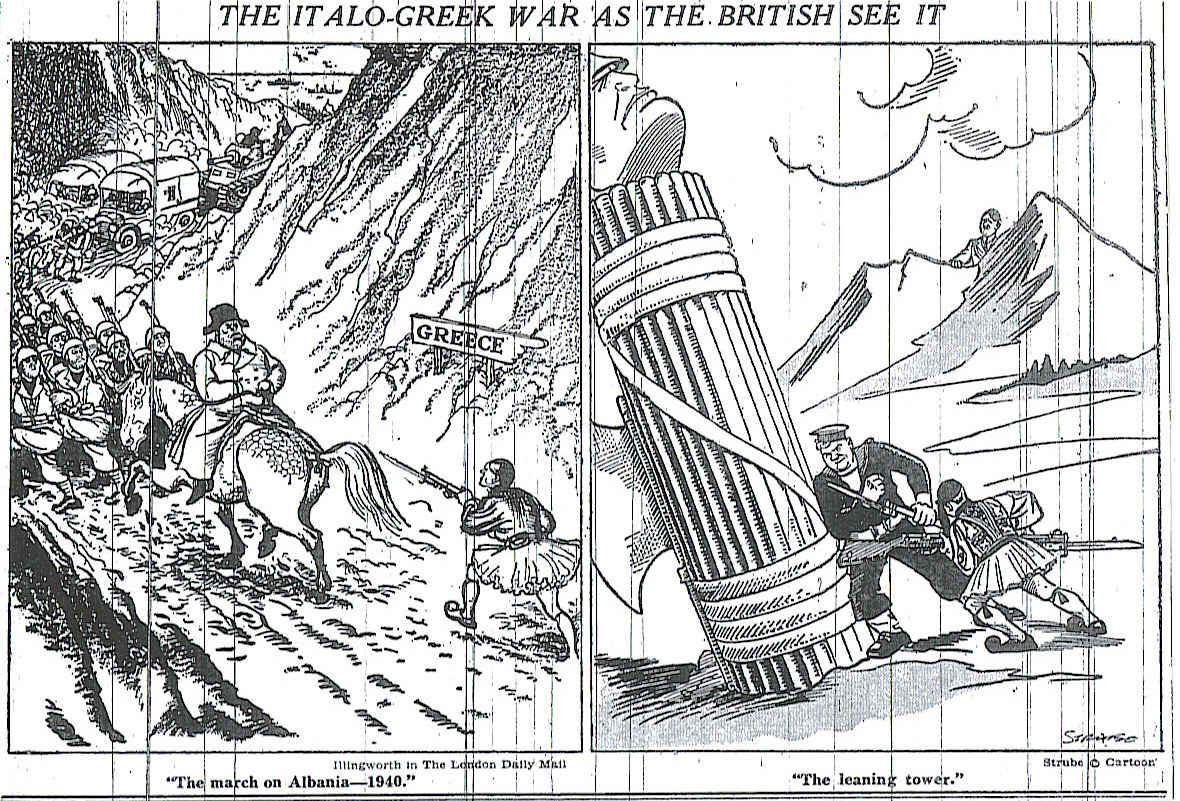

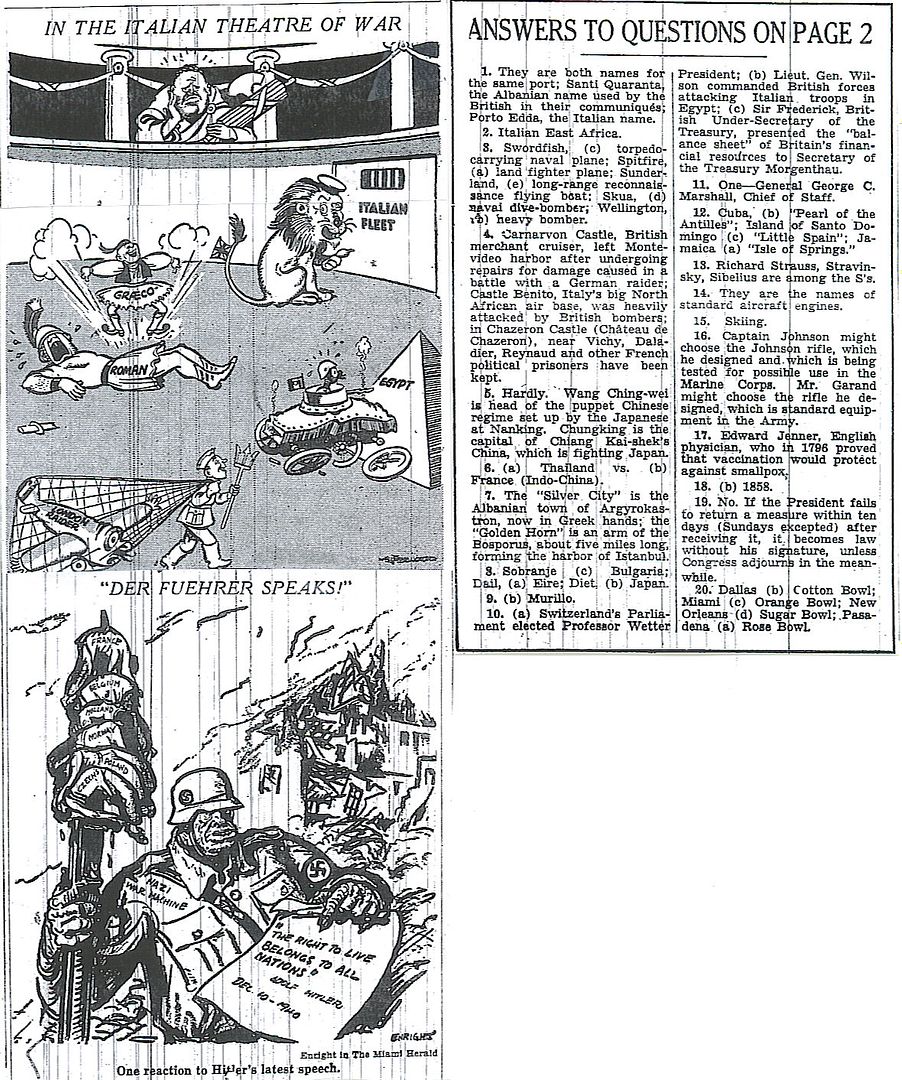

The British See Their Chance in Italy’s Defeat – 15-16

British Egypt Victory Big Blow to Mussolini – 17

Answers to Twenty News Questions – 18

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1940/dec40/f15dec40.htm

RAF attacks Berlin

Sunday, December 15, 1940 www.onwar.com

Over Germany ... Bomber Command strikes Berlin.

Over Italy... British planes bomb Naples. An Italian cruiser is reported damaged.

In Occupied France... The coffin of Napoleon II (1811-1832) is moved from Vienna to Paris and reburied in Les Invalides, on orders from Hitler.

In Ireland... Interned IRA members at Curragh Camp, near Dublin, continue to riot. In fighting with Irish police and military troops, one IRA member are reported shot.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/month/thismonth/15.htm

December 15th, 1940

UNITED KINGDOM: Destroyer HMS Cameron (one of the 50 US leases) is severely damaged by German bombing whilst in dry dock at Portsmouth. She topples over and is considered to be beyond repair and broken up. There are no casualties. (Alex Gordon)(108)

Destroyer HMS Ithuriel launched.

Submarine HMS P-32 launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

FRANCE:

Paris: The Germans ceremonially return the ashes of Napoleon II to the city.

This was Hitler’s idea of the supreme tribute to the French. He was to be re-interred during a solemn ceremony at the Invalides, attended by Hitler and Petain. Today is the anniversary of the day when Napoleon’s remains reached Paris from the island of Saint Helena. Everything was arranged, the precise order of ceremonies was worked out to the last detail, Petain and Hitler, standing side by side, would review the German honour guards, and they would both make speeches eulogising the son of Napoleon. The ceremonies took place but neither Hitler nor Petain was present. Petain refused to attend, chiefly because he was in the middle of a cabinet crisis, but also because he had not the slightest interest in the ashes. Someone told Hitler that Petain would not come because he was afraid of being kidnapped by the Germans. ‘It is contemptible to credit me with such an idea, when I meant so well!’ Hitler exploded.

GERMANY: The Germans release the papers (summaries of British CoS reports) captured by the raider Atlantis on November 11 to the Japanese. (Daniel Ross)

MEDITERRANEAN SEA: Submarine FS Narval mined off Tunisia. (Dave Shirlaw)

NORTH AFRICA:

Imperial troops cross the frontier into Libya.

The British take in a surprise raid the Halfaya Pass on the Libyan-Egyptian border. The remnants of the Italian Tenth Army withdrew to the fortress of Bardia. The Italians now reinforce the defences of Tobruk and the El Mekili-Derna line, where they station three divisions which they have summoned from the interior.

ATLANTIC OCEAN:

Italian submarine ‘Tarantini’ is torpedoed and sunk by submarine HMS Thunderbolt in the Bay of Biscay as she returns from North Atlantic patrol. The T-class submarine HMS Thunderbolt is the recomissioned/renamed HMS Thetis which failed to surface from its first submerged test trial in Liverpool Bay on 1st. June 1939. (Alex Gordon)

http://worldwar2daybyday.blogspot.com/

Day 472 December 15, 1940

Operation Compass. British attention now focuses on the port of Bardia, Libya, which they have surrounded. From 12.20 to 5.17 PM, monitor HMS Terror begins the bombardment of Bardia which is defended by 40,000 Italians commanded by General Annibale Bergonzoli, known as ‘Electric Whiskers’ due to his flaming red beard (now white) worn parted in the middle.

In the Bay of Biscay, 2 miles offshore near the Gironde Estuary, British submarine HMS Thunderbolt sinks Italian submarine Tarantini which is returning from patrol in the North Sea (all 58 hands lost). Free French submarine Narval sinks on a mine in the Mediterranean 40 miles Northeast of Sfax, Tunisia (all 54 hands lost). German motor torpedo boat S.58 sinks Danish steamer N. C. Monberg just off Yarmouth, England (8 crew, 1 gunner lost).

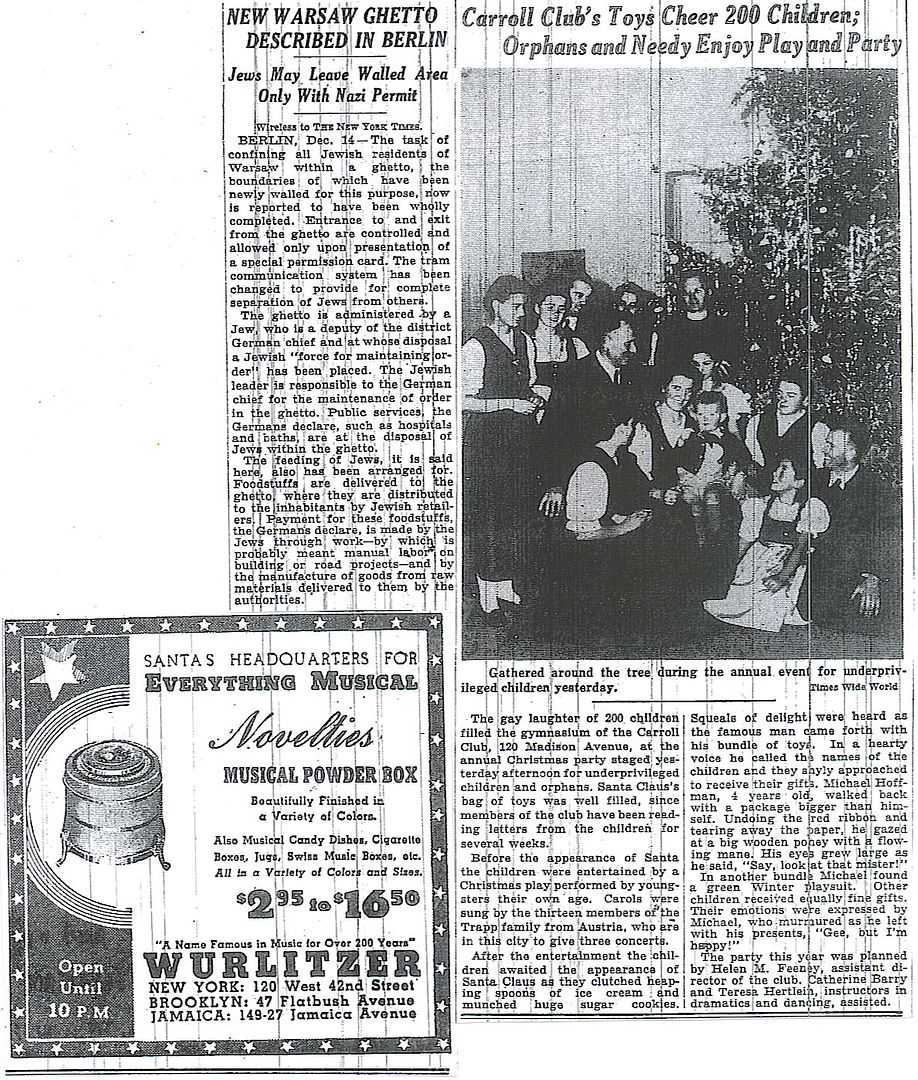

Great picture of the Von Trapp family.

The last two days’ NY Times have reported on the death of British Ambassador Lord Lothian. He had been a close friend of Lady Astor, who converted him to Christian Science. He died of a kidney infection, easily treatable with antibiotics. He refused to see a doctor in favor of a Christian Science practitioner.

Time magazine on Lothian’s death:

http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,765060,00.html

“”FOREIGN RELATIONS: Death of Lothian”

The ballroom of the Lord Baltimore Hotel was bright with patriotic bunting, with holly and mistletoe for the Christmas season. The Baltimore convention of the Farm Bureau Federation was coming to an end; 4,000 members crowded the ballroom floor and the balcony, stood against the wall in the back. To the silent crowd a small, intense counselor of the British Embassy in Washington, Nevile Butler, read the speech of his chief, Lord Lothian, who was announced as too ill to deliver it himself. It was a powerful statement, ending with an expression of faith in a final democratic victory, and a projection of the stable democratic world that could come after the war. It was in some respects Lord Lothian’s best speech.

Lord Lothian was indeed ill; he was dying. In the big, red-brick Embassy in Washington the Ambassador, a devout Christian Scientist, lay suffering the final ravages of uremic poisoning that to his faith was real only to the material world, unreal to the world of the spirit. Since his return to the U. S. from London three weeks before, the hearty, ruddy-cheeked Ambassador had gone out little. But sometimes he would ask old friends in for brief, quiet talk, of no immediate relation to war and his work, as if wanting to reassure himself that they were still there.

Three days before his death he had summoned a Christian Science practitioner from Boston, who was with him when he died. Suffering great fatigue and sleepiness, sometimes regaining consciousness enough to confer with his staff in his bedroom, he was apparently improving, relapsed on the night of his Baltimore speech. After his death at 2 a.m., the practitioner called a physician. The coroner, summoned where death occurs in the absence of a physician, certified that he had died of uremic poisoning and a heart and kidney condition.

The news was withheld for several hours. Then President Roosevelt, cruising on the Tuscaloosa in the Caribbean, sent a message to King George VI: “I am shocked beyond measure to hear of the sudden passing of my old friend and your Ambassador, the Marquess of Lothian. I am very certain that if he had been allowed by Providence to leave us a last message he would have told us that the greatest of all efforts to retain democracy in the world must and will succeed.”

All day official Washington paid condolence calls at the Embassy. The news hit London like word of a defeat in battle. Londoners were alarmed at its unexpectedness, doubly alarmed because it was announced by a coroner (in Britain the word coroner suggests suspicious circumstances surrounding the death).

Only when speculation about his successor began was Lord Lothian’s success fully apparent.* He had arrived in the U. S. five days before the war began, at a moment when the U. S. was doubly suspicious of all foreign—especially all British—propaganda. At his death a major U. S. concern was how aid to Britain could be increased. Though no historian would credit that great shift wholly to the Ambassador, there was no doubt that he had been an integral part of it. He had been right in his analysis of U. S. opinion and of the course of U. S. foreign policy; he had answered by word and action much U. S. suspicion of British ways; he had presented his view of the meaning of the war in half a dozen speeches which undoubtedly influenced U. S. thinking.

Last week, as public men began to assess Lord Lothian’s contribution, their tributes differed in degree but not in kind: few diplomats in U. S. history have accomplished so much in so brief and difficult a period. Yet their tributes gave no indication that before Lord Lothian’s brief U. S. career there had been a long ordeal of frustrations and setbacks that nothing in his manner suggested.

As a thin-faced, bookish Oxford graduate of 23, working in South Africa under the great liberal imperialist Lord Milner. he had absorbed Milner’s vision of the democratic Empire, steadily evolving toward the greater self-government of its various units, releasing the native genius of its different people, and yet unified under the structure of English constitutional law. He saw his years of work for a peaceful, democratic Empire set back by the impact of World War I, in which his only brother was killed. As Lloyd George’s secretary during the war, he had worked for the League of Nations, saw hope end in the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1930 a vast array of hereditary titles settled upon him, a bachelor, a democrat, and the last of his immediate line. His work for closer U. S.-British trade relations ended formally when he resigned from the Government over the Ottawa agreement. In the ‘30s, during the period of appeasement, he saw his last hope—that Adolf Hitler might still be brought into the fabric of European law & order by adjustments of the Versailles Treaty—end in the invasion of Czecho-Slovakia. And as he arrived in the U. S. as Ambassador, he saw the outbreak of the war which he believed Britain could not win unless she had U. S. help.

No sign of defeat marked Lord Lothian’s manner, just as, a few days before his death, he gave no sign of his illness. As a Christian Scientist he believed that his real life lay in the world of thought, and that he could go through unpleasant material experiences by not making a reality of them. Last week those who heard his Baltimore speech, with its description of Londoners under fire—stubbornly denying the ultimate reality of the bombings—felt that it applied as keenly to his own denial of his last illness.

On a cold, dismal day the flag-draped coffin was carried from the Embassy to a caisson, escorted up Massachusetts Avenue by a squadron of cavalry. The city grew quiet as the mounted band played a funeral march. The muffled drums and the dull clop-clop of the cavalry troop thudded in the grey air. Troopers carried the coffin into the grey, unfinished Washington Cathedral. A dull light edged through the rose window, on the guard of honor, the Union Jack, the Ambassadors, the Supreme Court Justices, the generals, the Cabinet officers, the wreaths of chrysanthemums from President Roosevelt, of laurel and palm from King George VI. In the middle of the service there was a special prayer: “Most merciful and compassionate God and Father of all men, we commend to Thy loving care and protection the people of Great Britain. In this hour of their need do Thou strengthen and sustain them. Guard and save them from the violence of their enemies. . . .”

A squad of cavalrymen carried the coffin from the Cathedral. There was a private service at Fort Lincoln, and the body was cremated. Then, with full military honors, the ashes of Philip Kerr, eleventh Marquess of Lothian, were placed in a vault in Arlington National Cemetery, beneath the mast of the U. S. S. Maine, until it would be seen fit to return them to his home.””

Gen. Patton of the Cavalry Sets Fast Pace for the Tank Corps - Army Knows His Name as Synonym for Daring Action - Washington Sunday Star, December 15, 1940.

The always-colorful figure of the old an new Army ... directed his force of modern American panzer troops ...

This picturesque and dashing officer ... can do a multitude of things and do them a bit better than most people...

There is something of the dash and color of Gen. J.E.B. Stuart about this many-sided officer who still has great love for the old cavalry although he is now launched on a career in mechanization...

His men swear by him and ... he would never order men to do anything in action that he wouldn't do himself. A social lion, well known in Washington drawing rooms ... he is, nevertheless, a hard-riding, hard-hitting "fightin' man" of the old school, with a mind to absorb and improve on new military ideas.

from The Patton Papers: 1940-1945 by Martin Blumenson

Thanks for the Ping, Homer!

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.