Posted on 03/10/2025 6:10:44 AM PDT by Red Badger

Photo of a (currently) dry, dusty cave south of the Atlas mountains. In the past, water was flowing down this large stalagmite formation. We date tiny pieces of stalagmite (~0.25g) to establish when the cave was wet in the past. Credit: Ben Lovett

Analysis of Moroccan stalagmites reveals that the Sahara received increased rainfall between 8,700 and 4,300 years ago, supporting early herding societies. This rainfall, likely driven by tropical plumes and monsoon expansion, narrowed the desert, improved habitability, and facilitated human movement.

Analysis of stalagmite samples from caves in southern Morocco has revealed new details about past rainfall patterns in the Sahara Desert. Researchers from the University of Oxford and the Institut National des Sciences de l’Archéologie et du Patrimoine found that rainfall increased between 8,700 and 4,300 years ago, significantly influencing ancient herding societies. Their findings are published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Stalagmites—rock formations that grow upward from cave floors—serve as valuable records of past climate conditions. Their formation requires rainwater to percolate through soil and drip onto the cave floor, meaning their presence indicates historical rainfall. The discovery of stalagmites near the edge of the world’s largest hot desert provided researchers with an opportunity to reconstruct past precipitation trends.

By analyzing trace amounts of uranium and thorium in the stalagmites, the researchers were able to determine when these formations grew, which in turn pinpointed periods of increased rainfall. Their findings confirm that the Sahara experienced wetter conditions during the African Humid Period, between 8,700 and 4,300 years ago.

“It is fabulous to see this research published after years of careful study. It was exciting to find and explore caves in southern Morocco during my fieldwork in 2010. And it is very rewarding that our measurements and interpretations fit so well with archaeological and environmental records from the wider region,” says Dr. Julia Barrott, study co-author, Impact and Learning Officer and Research Fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, Oxford.

Climatic Impact on Early Societies

This time period coincides with a rise in the number of Neolithic archaeological sites in the region south of the Atlas Mountains, which then plummeted when arid conditions resumed. The research team believes that this highlights the importance of a favorable climate on these early pastoralist societies, which relied on rainfall for their livestock.

ASD-1 is an example stalagmite used in our study, from a cave found by Dr. Julia Barrott during her 2010 fieldwork. We are careful to work with samples that are already broken from natural processes, e.g. by earthquakes or by rock fall within the cave. Stalagmites grow from bottom to top with banding similar to tree rings. Accurate chronology shows that the sample started to grow shortly before 6000 years ago. Credit: Dr. Julia Barrott

But the impact was not just local; the South-of-Atlas region is significant because the land slopes southwards into the heart of the Sahara. As a result, enhanced rainfall during this period refilled major aquifers and increased river flow in the desert. This would have made it easier for populations to travel into this inhospitable environment to connect with other groups and exchange both goods and knowledge.

The research team also analyzed the amounts of different oxygen isotopes contained within the calcium carbonate stalagmite to investigate the mechanism which supplied the rainfall. They believe that additional rainfall came from tropical plumes, huge bands of clouds in the upper atmosphere, which can transport moisture from the tropics into the subtropics. This is the first study to show the influence of tropical plumes on this region in the past.

A beautiful example of a cave system from south of the Atlas mountains, with Julia Barrott and Chris Day for scale. Credit: Ben Lovett

At the same time, there is evidence from other sites that the West African Monsoon encroached into the Sahara from the south, and that combined with tropical plume rainfall to the north, this suggests that the desert narrowed significantly in this period. This improved habitability north and south of the central Sahara, increased recharge to rivers, and a narrower desert may have encouraged movement by people across the Sahara, during a key period in the development of land use and animal production.

Contributions to Climate Research

This new record on the northern edge of the Sahara adds vital information for understanding how climate has changed in this region during human habitation. These stalagmites add to information from other climate archives, such as Atlantic ocean cores, to understand variations in the Saharan environment. The ocean cores are located too far away to identify regional changes with precision. Contrastingly, this stalagmite record is ideally located for this task.

“It has been exciting experiencing how much we can learn from small pieces of limescale that form underground. I worked on the most recent 1000 years of this palaeoclimate record during my master’s project, and now I am working to better quantify the exact levels of increased rainfall during my PhD project,” says Sam Hollowood, study co-author and DPhil student at Oxford’s Department of Earth Sciences.

The evidence of tropical plume rainfall provided by this study is also important for researchers trying to understand how rainfall patterns will change in the South-of-Atlas region in the future. Because tropical plumes brought rainfall to the area in the past, it opens up the possibility that they could do so in the future. The research team is keen to investigate this further by developing more quantitative reconstructions of rainfall amounts in the past.

Reference:

“Evidence for the role of tropical plumes in driving mid-Holocene north-west Sahara rainfall”

by Hamish O. Couper, Christopher C. Day, Julia J. Barrott, Samuel J. Hollowood, Stacy A. Carolin, Ben Lovett, Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, Nick Barton and Gideon M. Henderson, 9 January 2025, Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2024.119195

PinGGG!.......................

Climate change IS real.

It’s just not anthropogenic

LOL!!

Tear down those pyramids, they caused it.

Quite so.

The industrial age sure put a stop to that!... oh wait.

It was the goats. They ate everything green until nothing was left but the sand.

I thought we already knew that it used to be green?

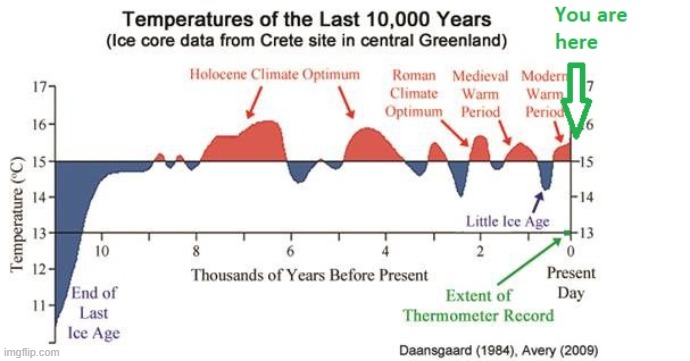

8,000 years ago we weren't coming out of the horrible Little Ice Age. I know when we think of deserts we think heat = dry. But it turns out that during the cooling periods is when areas are more liable to have megadroughts.

This cave stalagmite yields an actual timeline...............

So.....I was reading this in my Weekly Reader 60 years ago and have seen many books/mags showing cave paintings of lush greenery and critters in the Sahara caves in later life...some more recent art showed greenery in what is not desert as late as the Phoenician, Greek and even Roman eras.

I was taught the ever rising Himalayas is what changed the weather patterns to cause both the Sahara and Gobi Deserts.

Bu they also taught me life began at conception and there were only two genders.

ahh

If dating is accurate, the start of Egyptian building of giant pyramids was before the current desertification.

I thought we already knew this?

For decades.

The scientists probably had to walk past the cave paintings depicting people hunting animals that can no longer live in the Sahara.

later

Now we have a timeline.................

I remember reading the ancient Sahara was green in a book over 65 years ago. Either in a LIFE or NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC magazine or book. This is not new info.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.