Skip to comments.

The nbC Eligibility Brainwashing Runs Deep

The Post & Email Newspaper ^

| 12 Jan 2024

| Joseph DeMaio

Posted on 01/12/2024 11:30:39 PM PST by CDR Kerchner

(Jan. 12, 2024) — Following up on the presidential eligibility posts recently appearing at The P&E here and here, the New York Post – founded, BTW, by Alexander Hamilton in 1801 – has come out and slammed President Trump’s suggestion that Nikki Haley is likely ineligible to the presidency. The Post labels President Trump’s suggestion that Haley is not a “natural born Citizen” (“nbC”) under the Constitution as being “bonkers.”

Really? Where to start, where to start?

First, President Trump’s post questioned Nikki Haley’s eligibility primarily in terms of her pursuit of the presidency, but it also addressed her likely disqualification for the vice-presidency under the 12th Amendment. Problematically, the Post article misinforms its readers when it asserts that “[t]he 12th Amendment lays out the procedure for electing the president and vice president and makes no mention of eligibility.” (Emphasis added) Alterian, Inc.

Even the most cursory review of the actual language of the 12th Amendment reveals that its final sentence states: “But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.” (Emphasis added) Like the caveman said in the Geico commercial from the 1980’s, “Yeah, next time, maybe do a little more research.”

Second, the author of the NY Post article, one Emily Crane, although a journalist for some 15 years with a B.A. degree in “Communications Studies” from Western Sydney University (yes, Virginia, in Australia…, not the United States), does not claim to be a U.S. Constitution scholar. Instead, she relies for her assertions on, among others, one Geoffrey Stone, a University of Chicago professor who, she claims, is an expert on constitutional law.

Professor Stone is quoted in the Post article ...

(Excerpt) Read more at thepostemail.com ...

TOPICS: Chit/Chat; History; Military/Veterans; Miscellaneous

KEYWORDS: 000001haleynotanbc; 000001wongwrongwrong; birther; commanderinchief; disinformation; eligibility; gaslighting; josephdemaio; naturalborncitizen; nikkihaleyineligible; presidential

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 ... 181 next last

To: DiogenesLamp; woodpusher

You cannot pass a statute to change the laws of nature. And who has argued that a statute can change the law of nature?

However, it is within the powers of a country to decide who counts as a citizen, and who gets the privileges accorded to a citizen. Such authority lies with the Congress.

The issue is that whatever disagreements there are regarding the meaning of "natural born citizen", the differences between "natural born citizen", "native-born citizen", and "citizen by birth" became de facto and de jure nil within a generation or two of the Founding Fathers, if not earlier; especially with regards to those born within America and subject to her jurisdiction.

You may cite various authorities regarding what the definition of "natural born citizen" is, whereas others will dispute your definition. If you don't want to leave differences of interpretation up to the Supreme Court, then you're going to need a Constitutional amendment codifying the meaning of the term.

That's just the way it is.

Also, i've posted that lawbook from Pennsylvania which flat out says our "citizenship" comes from Vattel, and the people most likely to know what was intended by the Convention (held in Philadelphia in 1787) was the Philadelphia legal community, which is exactly where that book came from.

Aren't you getting tired of citing the same book that you've been refuted on at least three times by my count?

21

posted on

01/13/2024 10:34:39 AM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

And who has argued that a statute can change the law of nature? You did.

"If it means that much to you, advocate for Congress to introduce a statute, or for a Constitutional amendment, to codify the definition of “natural born citizen” ...

Congress cannot change natural law, and not even a constitutional amendment can do that. It can change the eligibility requirements, but what you are suggesting is equivalent to an amendment that can change men into women.

It is beyond the power of law or amendment to do that.

However, it is within the powers of a country to decide who counts as a citizen, and who gets the privileges accorded to a citizen. Such authority lies with the Congress.

Congress has the power of "naturalization." They have no power at all to declare someone "natural born" who isn't. They can make all the citizens they want through "naturalization", but they can make none through nature.

Aren't you getting tired of citing the same book that you've been refuted on at least three times by my count?

Well you clearly have trouble with your understanding. The book has never been refuted by my count. It *IS* proof that this was what they intended in 1787.

You have nothing like it on your side. What you've got is William Rawle making the claim that citizenship is based on English common law in *1828*!!!. And he was wrong, and told by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court he was wrong in 1803! Unanimously! (Negress Flora vs Joseph Grainsberry.)

You don't get much wronger than William Rawle was, and yet he is the most prominent "authority" upon which people have based this English law claims for natural born citizen.

22

posted on

01/13/2024 10:46:45 AM PST

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: AnotherUnixGeek

23

posted on

01/13/2024 11:12:05 AM PST

by

CDR Kerchner

( retired military officer, natural law, Vattel, presidential, eligibility, natural born Citizen )

To: thecodont

24

posted on

01/13/2024 11:19:59 AM PST

by

CDR Kerchner

( retired military officer, natural law, Vattel, presidential, eligibility, natural born Citizen )

To: CDR Kerchner; All

Until there’s a USSC case that decides this, it’s arguing how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. In short a waste of time! The USSC is not going to take up the case! Why you ask? A negative decision could invalidate the presidential terms of “The One”! So not going to happen! The precedent like or not has been set. Courts like precedents!

What I have typed should not be interpreted that approve the situation. I just understand what it is!

25

posted on

01/13/2024 11:27:45 AM PST

by

Reily

(!!)

To: DiogenesLamp; woodpusher

You did. No I didn't; I deny that the definition of "natural born citizen" is so fixed as to be dependent solely on natural law theory, as you argue.

Congress cannot change natural law, and not even a constitutional amendment can do that. It can change the eligibility requirements, but what you are suggesting is equivalent to an amendment that can change men into women. It is beyond the power of law or amendment to do that.

A law cannot change a man into a woman. But a law can change the criteria for citizenship.

They have no power at all to declare someone "natural born" who isn't.

The application of "natural born" can vary depending on what law system you follow: the "jus soli" from the English common law or the "jus sanguinis" of civil law. The English parliament had numerous instances of statutorily defining certain classes of subjects as "natural born".

Well you clearly have trouble with your understanding. The book has never been refuted by my count. It *IS* proof that this was what they intended in 1787.

You literally misattributed a page from one book to another, for starters.

You have nothing like it on your side. What you've got is William Rawle making the claim that citizenship is based on English common law in *1828*!!!. And he was wrong, and told by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court he was wrong in 1803! Unanimously! (Negress Flora vs Joseph Grainsberry.) You don't get much wronger than William Rawle was, and yet he is the most prominent "authority" upon which people have based this English law claims for natural born citizen.

I've seen so many sources and citations thrown your way over these past months on various threads that I can only conclude that you must be very forgetful (to be charitable).

But to be frank, your reliance on Vattel's understanding from a treatise on international law is outweighed by that which supports common law understanding (your incorrect claim that Rawle is the only source of such an understanding notwithstanding):

26

posted on

01/13/2024 11:38:37 AM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

Regardless of whether or not there is quite literally nothing new, it points to original intent interpretation of the Constitution. Of course, if that is out of fashion as way back as 2008 it should have been adjudicated as such and not just proclaimed (like ‘No 2020 Election Fraud’ was never adjudicated ).

At any rate the article’s arguments are almost indisputable without bias/illogic or just plain failure to get a grip. MOST telling is “ Why is nbC in the Constitution ?”

-fJRoberts

27

posted on

01/13/2024 11:52:59 AM PST

by

A strike

(Words can have gender, humans cannot.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

"...it is within the powers of a country to decide who counts as a citizen, and who gets privileges accorded to a citizen. Such authority lies with the Congress." Such fundamental misunderstanding; I suspect you think the UnitedStates is a democracy too.

28

posted on

01/13/2024 12:06:59 PM PST

by

A strike

(Words can have gender, humans cannot.)

To: A strike

Such fundamental misunderstanding; I suspect you think the UnitedStates is a democracy too. The USA is a constitutional republic in terms of its originating structure (even if it is 'de facto' a democracy now in many ways). However, I don't know why you find it controversial that a nation can determine for itself who shall and shall not be citizens of itself.

The English parliament for centuries had statutorily extended "natural born" status to various classes. Congress, per the Constitution, is authorized per Article 1, Section 8, Clause 4 to determine the rule of naturalization, i.e. the power to confer citizenship to others (and the duties, privileges, and immunities that come with it).

But, in principle, any nation has the power to determine who is and is not a citizen of itself. That's kind of the point, is it not?

29

posted on

01/13/2024 12:12:22 PM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: A strike

30

posted on

01/13/2024 12:55:08 PM PST

by

CDR Kerchner

( retired military officer, natural law, Vattel, presidential, eligibility, natural born Citizen )

To: DiogenesLamp; woodpusher; Fury

Also, just for fun, I decided to do a little bit of digging on this 1803 case that Rawle was a part of that you keep referencing.

First, Grainsberry is a typo; it was "negro Flora vs. Joseph Graisberry" per one source, and "negro Flora v. Graisberry's Executors" per another, and "Negress Flora v. Joseph Graisberry" from a third.

Second, based on review of what I can see, the case was petitioned by Flora in 1795 (with William Rawle as one of her counsels) with the view of establishing that slavery was incompatible with Pennsylvania's constitution. The details of the case, as disclosed in these sources, was about Flora's status as a slave in light of Pennsylvania's own state constitution.

From Legal Miscellany: "The High Court of Errors and Appeals and Negro Suffrage" —

[...]

From Cory James Young's doctorate dissertation "FOR LIFE OR OTHERWISE: ABOLITION AND SLAVERY IN SOUTH CENTRAL PENNSYLVANIA, 1780-1847" —

(Of particular note, per the index of slavery cases in the PA Supreme Court included with this dissertation, "Negro Flora v. Joseph Graisberry" was not reported; as such, there does not seem to be an extant copy of the actual court case and judicial opinions in question.)

From Mary Stoughton Locke's 1901 book " Anti-slavery in America from the Introduction of African Slaves to the Prohibition of the Slave Trade (1619-1808)"—

And lastly, from the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Volume 36, No. 2, published in 1912)—

All of these sources cited point to Rawle's argument being rejected not because of his arguments regarding "natural born citizenship", but rather that the very status of "slave" was not inconsistent with Pennsylvania's own constitution. In fact, the matter of who is and is not a "natural born citizen" is not mentioned even once.

Thus, I must ask: what evidence do you have supporting your repeated contention that the Flora v. Graisberry case can be construed as a rejection of the common law understanding of "natural born citizen"?

31

posted on

01/13/2024 12:58:25 PM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

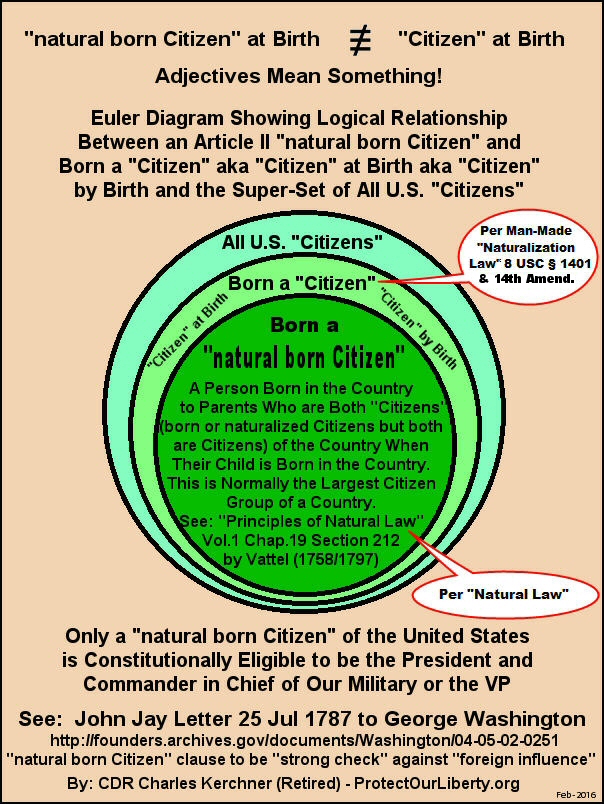

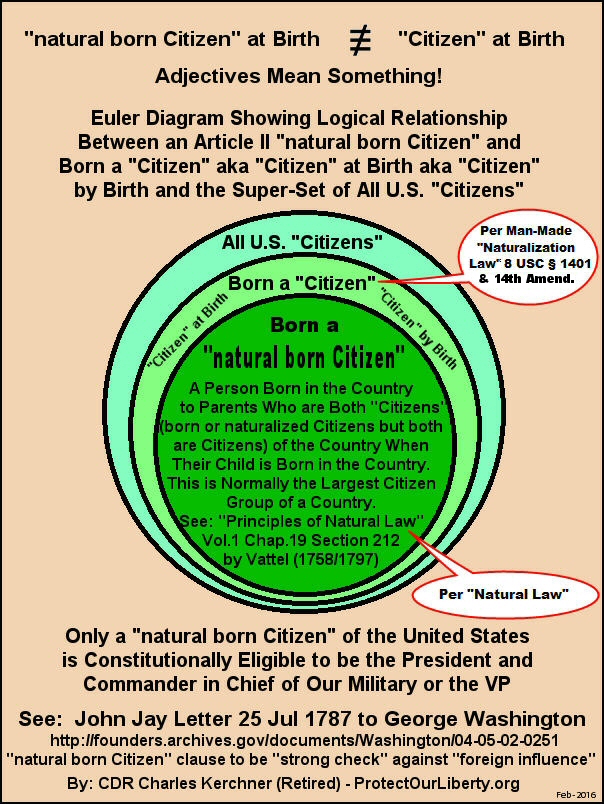

You keep manipulating and conflating terms and language. A nation can determine who are its "Citizens". But per Natural Law and the Laws of Nature it cannot determine who is a "natural born Citizen" of the country. The "Citizens" procreate the "natural born Citizen" kind when two Citizen parents (born or naturalized themselves) have their child born in the country. See the clear cut definition found in the preeminent legal treatise on The Law of Nations of Principles of Natural Law by Emer de Vattel (1758/1797), which the founders and framers used to justify the Revolution and write the founding documents. That treatise was also widely used by the U.S. Supreme Court during the first 50 years to start establishing U.S. Federal Common Law. Vattel was cited in the SCOTUS Venus case of 1814. For Vattel's clear cut definition of "natural born Citizen", see Vol.1 Chapter 19 Section 212:

https://lonang.com/library/reference/vattel-law-of-nations/vatt-119/ Also Mr. Ultra Sonic, see the Euler Logic Diagram below if you have trouble with adjectives modifying a noun, and understanding that a "natural born Citizen" is a subset of all "Citizens", the largest subset for most counties, i.e., the children born in the country of its citizen parents, plural. But it seems to me you do not wish to be logical but instead choose to use social engineering skills to manipulate terms and language to push your Progressive agenda to subvert the U.S. Constitution original intent, meaning, and purpose (the WHY) for the "nbC" term.

32

posted on

01/13/2024 1:10:42 PM PST

by

CDR Kerchner

( retired military officer, natural law, Vattel, presidential, eligibility, natural born Citizen )

To: DiogenesLamp; woodpusher; Fury

A brief post-script to post #31.

One more source, that was referenced by Mary Stoughton Locke: "A sketch of the laws relating to slavery in the several states of the United States of America", by George M. Stroud—

On page 143, mention is made of how in Pennsylvania, "the birth place of efficient hostility to negro bondage, the highest judicial tribunal of the state, has pronounced as the result of its solemn deliberation on a similar article of her constitution, that slavery was not inconsistent with it." The corresponding footnote follows, which spills over to page 144:

On various previous threads, you've stated the following (bold is emphasis mine):

"William Lewis was William Rawle's co-counsel in Negress Flora vs Joseph Grainsberry, where Rawle tried to float his English common law theory, and was shot down unanimously."

"William Rawle was the man who wrote a book that caused the most damage to American's understanding of the meaning "natural born citizen." He was an English lawyer that came to Philadelphia after the Revolutionary war to practice law. He became president of the abolition society of Pennsylvania, and at the time, other states were having success abolishing slavery through court decisions declaring slaves "free." He set about to replicate this in Pennsylvania courts. A case he took on was Negress Flora vs. Joseph Grainsberry. (Not sure I spelled that right) He lost. It went to the Pennsylvania Supreme court and he lost unanimously. He put forth his claim that because English common law declared anyone born on the soil to be a "citizen", slaves could not be slaves, because they were "citizens." The Pennsylvania Supreme court rejected this argument."

"The trouble is, it was not true, as the Pennsylvania Supreme court had made clear to him on more than one occasion. Rawle was deliberately lying, and he *KNEW* he was deliberately lying. He was trying to make the argument that slaves were citizens too, and therefore could not be slaves, and so he misled everyone in an effort to free the slaves through the back door of citizenship law. He had been trying this tactic since the 1790, and the courts kept rejecting him. His efforts to free the slaves has only caused the rest of the nation to be confused about what the framers intended in 1787 when they insisted on "natural born citizen.""

"He spread the idea that "natural born citizen" is based on English Common Law, and he did this despite the fact that he was unanimously rebuked in this view by the entire Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1801,(I think) in the case of "Negress Flora vs Joseph Gainsberry"."

Etcetera.

If the details of this case are not on any surviving books of reports, and the only declaration from the Pennsylvania court can be paraphrased as 'slavery is not outlawed by Pennsylvania's constitution' (with no commentary regarding citizenship by birth or otherwise), how can you justify any of the claims you've made?

33

posted on

01/13/2024 1:16:59 PM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: All

34

posted on

01/13/2024 1:32:59 PM PST

by

CDR Kerchner

( retired military officer, natural law, Vattel, presidential, eligibility, natural born Citizen )

To: CDR Kerchner

See the clear cut definition found in the preeminent legal treatise on The Law of Nations of Principles of Natural Law by Emer de Vattel (1758/1797), which the founders and framers used to justify the Revolution and write the founding documents. Not only do I fail to see why a treatise on **international law** would have any bearing on a nation's own standards for determining citizenship, your citation of the Venus case is malapropos: no question of birthright citizenship was under discussion or investigation. All of the citations of Vattel were in service for determining a dispute regarding property rights, forfeiture, and restitution in a case where seizure of ships on the high seas was involved...in other words, a case wherein the Law of Nations actually comes into play, because it involved a dispute between two or more nations! (It should also go without saying that Vattel's definition is tied to the civil law system of the European continent; it has no bearing on the English common law, which the American system of law is derived from.)

Emer de Vattel was dead and buried before the Declaration of Independence, much less the Constitution. A book on international law has no controlling interest on the domestic laws of a nation, especially when you have over two centuries of Federal and State court decisions to work with.

So you can stow away your "Euler Logic Diagram", because it invokes a category error: the second circle relies on actual United States statute, whereas the third and inmost circle relies on a definition provided by a Swiss civil law specialist in a book focusing on international law. Why should Vattel take precedence over the overwhelming extant evidence favoring the common law notions of "jus soli", insofar as America is concerned?

35

posted on

01/13/2024 1:35:21 PM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

Of course there can be no rational dispute that a nation can determine the parameters of its citizenry.

The pointed out question at hand Here is whether the Congress can determine definition of natural born Citizen.

As the founders were EXPLICITLY breaking away from ‘English law’, while educational it carries no necessary weight re the US Constitution as written.

-fJRoberts-

36

posted on

01/13/2024 1:41:16 PM PST

by

A strike

(Words can have gender, humans cannot.)

To: Ultra Sonic 007

Don’t go starting to use logic, reasoning and the law on FR!!!!

37

posted on

01/13/2024 1:49:04 PM PST

by

Oystir

To: Ultra Sonic 007; DiogenesLamp; CDR Kerchner

‘k scholar, WHY was the term ‘natural born Citizen’ inserted as a qualification if there was no distinction in the Founders minds between nbC and just anyone born here ?

Your ‘arguments’ employing years of subsequent legal mumbo-jumbo regarding nbC are similar to those attempting to accrue legitimacy to the question of ‘what is a woman’.

-fJRoberts

38

posted on

01/13/2024 1:57:09 PM PST

by

A strike

(Words can have gender, humans cannot.)

To: A strike

As the founders were EXPLICITLY breaking away from ‘English law’, while educational it carries no necessary weight re the US Constitution as written. That they broke away from the English as their sovereign, conceded; that they broke away from the common law system itself, denied.

(Underline is emphasis mine.)

From United States v. Rhodes in 1866: "All persons born in the allegiance of the king are natural born subjects, and all persons born in the allegiance of the United States are natural born citizens. Birth and allegiance go together. Such is the rule of the common law, and it is the common law of this country, as well as of England."

From Ludlam v. Ludlam in 1863: "The same question is presented, therefore, in this respect, which arose in Lynch v. Clark (1 Sandf. Ch. R., 583), where it is, I think, very clearly shown that, in the absence of any statute, or any decisions of our own courts, State or National, on the subject, the question of citizenship can only be determined by reference to the English common law, which, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, was, to a greater or less extent, recognized as the law of all the States by which that Constitution was adopted. This conclusion does not involve the question very earnestly debated soon after the organization of the government, whether the common law of England became the law of the Federal Government, on the adoption of the Constitution. (1 Tucker's Blackstone, appendix E, p. 378; 1 Story's Com. on the Const., § 158, and note 2; Madison's Rep. to the Virginia Legislature, 1799, 1800; Instructions of Virginia to her Senators in Congress, January, 1800; Speech of Mr. Bayard on the Judiciary, 2 Benton's Debates, 616; 1 Kent's Com., 331, 343.) It only assumes, what has always been conceded, that the common law may properly be resorted to in determining the meaning of the terms used in the Constitution, where that instrument itself does not define them. Judge Tucker, at the close of his essay against the common law powers of the Federal Government, says: "We may fairly infer, from all that has been said, that the common law of England stands precisely upon the same footing in the Federal Government and the courts of the United States, as such, as the civil and ecclesiastical laws stand upon in England, that is to say, its maxims and rules of proceeding are to be adhered to, whenever the written law is silent, in cases of similar or analogous nature.""

From Zephaniah Swift's 1795 treatise "A system of the laws of the state of Connecticut" (take note that Swift was member of CT's House of Representatives, a judge on the Supreme Court of CT from 1801 to 1819 [serving as Chief Justice for the last 13 years of his tenure], and ran a successful law school, among other things):

And so on.

39

posted on

01/13/2024 2:00:09 PM PST

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: Oystir

“...logic, reasoning and the law”

as if you could recognize it if it hit you upside the head,

back under the bridge

40

posted on

01/13/2024 2:01:43 PM PST

by

A strike

(Words can have gender, humans cannot.)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 ... 181 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson