Skip to comments.

Happy Secession day!

July 4, 2023

| Me.

Posted on 07/04/2023 11:54:31 AM PDT by DiogenesLamp

Today we celebrate the 13 original states seceding from the Union and forming a confederacy. (Articles of Confederation.)

TOPICS: History; Miscellaneous; Society

KEYWORDS: confederacy; dunmoreproclamation; frdemtrolls; independence; nostalgicdepression; notthisshitagain; secession; skinheadsonfr

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20 ... 81-100, 101-120, 121-140 ... 181-195 next last

To: jmacusa

[jmacusa #53] "Slavery ended in NJ in 1809." [woodpusher #95] "Despite the 13th Amendment, New Jersey stubbornly resisted abolition until January 1866."

[jmacusa #96] "It ended none the less, resistance or not. NJ contributed to fighting to preserve the Union and ending slavery."

Everybody knows slavery ended. You said it ended in New Jersey in 1809. The New Jersey government official website says it ended in 1866. You seem to be experiencing extreme difficulty in acknowledging your claim missed by 57 years.

In its alleged continued fight to end slavery, New Jersey refused to ratify the 13th Amendment until after it had already been certified into law without the vote of the recalcitrant state of New Jersey. New Jersey acknowledges itself as being the last of the states to have slavery.

https://nj.gov/state/historical/his-2021-juneteenth.shtml

New Jersey, The Last Northern State to End Slavery

[excerpt]

Slavery’s final legal death in New Jersey occurred on January 23, 1866, when in his first official act as governor, Marcus L. Ward of Newark signed a state Constitutional Amendment that brought about an absolute end to slavery in the state. In other words, the institution of slavery in New Jersey survived for months following the declaration of freedom in Texas. To understand this historical development, one needs to take a step back to 1804 when New Jersey passed its Gradual Abolition of Slavery law—an act that delayed the end of slavery in the state for decades. It allowed for the children of enslaved Blacks born after July 4, 1804 to be free, only after they attained the age of 21 years for women and 25 for men. Their family and everyone else near and dear to them, however, remained enslaved until they died or attained freedom by running away or waiting to be freed.

To: DiogenesLamp

It is my recollection that the US government owned slaves for a month or so at the beginning of the war. (Captured Contraband.)Then they decided it was embarrassing, so they freed them.

See Laura F. Edwards, "A Legal History of the Civil War and Reconstruction; A Nation of Rights, Cambridge University Press, 2015, page 20.

It's [martial law] first controversial use came from John C. Fremont, who commanded federal troops to Missouri. After removing the state's secessionist governor, Fremont declared martial law in the entire state without obtaining Lincoln's permission. He then used those powers to abolish slavery and confiscate secessionists' property, also without Lincoln's permission. It was not so much the declaration of martial law as what Fremont did with it that caused trouble. … He was a strong opponent of slavery, not just in the territories, but also in states where it already existed. No wonder that Lincoln did not take kindly to Fremont's efforts to supplant his authority and his political agenda, which promised to leave slavery alone so as to keep Border States in the Union. The showdown ended when Lincon removed Fremont from command.

See Lerone Bennett, Jr., "Forced Into Glory," Johnson Publishing Company, 2000, pp. 30-31:

Far from being "the great emancipator," he came clse to being the great contra-emancipator. When General John Charles Fremont freed Missouri slaves, Lincoln reenslaved them, pleading Kentucky and the need to assuage the fears and interests of slaveholders and supporters of slaveholders. When his friend, Major General David Hunter, freed slaves in Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, Lincoln reenslaved them (CW 5:222-3). When Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler moved too forcefully against slavery in Louisiana, he was sacked and put on Lincoln's white list of troublesome antislavery generals. When John W. Phelps, Donn Piatt and other Union officers threatened the interests of slaveowners, the were either sacked, denied promotion, or cashiered out of the service.

CW 5:222-3 provides Lincoln's May 19, 1862 Presidential Proclamation regarding the acts of General Hunter, excerpted below.

I, Abraham Lincoln, president of the United States, proclaim and declare, that the government of the United States, had no knowledge, information, or belief, of an intention on the part of General Hunter to issue such a proclamation; nor has it yet, any authentic information that the document is genuine. And further, that neither General Hunter, nor any other commander, or person, has been authorized by the Government of the United States, to make proclamations declaring the slaves of any State free; and that the supposed proclamation, now in question, whether genuine or false, is altogether void, so far as respects such declaration. I further make known that whether it be competent for me, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, to declare the Slaves of any state or states, free, and whether at any time, in any case, it shall have become a necessity indispensable to the maintainance of the government, to exercise such supposed power, are questions which, under my responsibility, I reserve to myself, and which I can not feel justified in leaving to the decision of commanders in the field. These are totally different questions from those of police regulations in armies and camps.

To: jmacusa; woodpusher

The clause prohibited the Federal govt from from limiting the importation of ‘’persons''. It does not use the word ''slave. Are ya gonna lie to yourself about what they mean? Woodpusher, could you provide the text of Congress's law banning the import of "persons" so we can see what sort of "persons" they were referring to by stopping their import in 1808?

103

posted on

07/10/2023 8:09:08 AM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: jmacusa

No you didn’t. Answer the question. So what is the question? As I said, I have already answered the "Would the South continue to have slavery?" question.

I said they would likely continue to have slavery for between 20 to 80 years longer, but likely not longer than that.

I said the North would also continue having slavery for between 20 to 40 years longer.

If this is not the question you wanted me to answer, tell me what is the question you wanted me to answer.

104

posted on

07/10/2023 8:18:07 AM PDT

by

DiogenesLamp

("of parents owing allegiance to no other sovereignty.")

To: woodpusher; jmacusa; x; DiogenesLamp

woodpusher:

"You couldn't teach anybody anything unless it appears Wikipedia." It's true that I don't try to depend on my own memory to keep the facts straight, and Wikipedia is a convenient source, mostly free and ad-free, of "common knowledge."

And unlike some younger people, I don't have access to whole electronic libraries full of useful data.

Maybe someday I'll figure out how they do that, but one problem is, we are already at the point of overloading with far too much information for the average person to absorb.

I'm not certain it helps arguments to load them down with very lengthy quotes from obscure sources...

woodpusher: "But then as early as 1803, a loophole was created that [essentially] said: “Bring your slaves to Illinois.

It’s fine.

Just go through the formality of an indenture contract.”

Some contracts were for 99 years."

Right, I totally understand your point here, but my point totally sailed right over your head, didn't it?

My response was:

"...in 1845 Illinois supreme court freed any remaining indentured ex-slaves."

So, your 99 years turned out to be something considerably less, didn't it?

woodpusher: [slaves] "They worked in Illinois but were the slaves of another state.

In other words, after Illinois proclaimed itself slave-free, slaves in Ilinois were sheep-dipped in another state."

Right, and before the 1857 SCOTUS Dred Scott ruling, such practices were often disciplined by state courts, even in the South, who recognized Northern states' laws automatically manumitting slaves who were kept too long in a Northern state.

Those are the grounds on which Dred Scott sued for his freedom and which SCOTUS Chief Crazy Roger Taney struck down in his insane opinions.

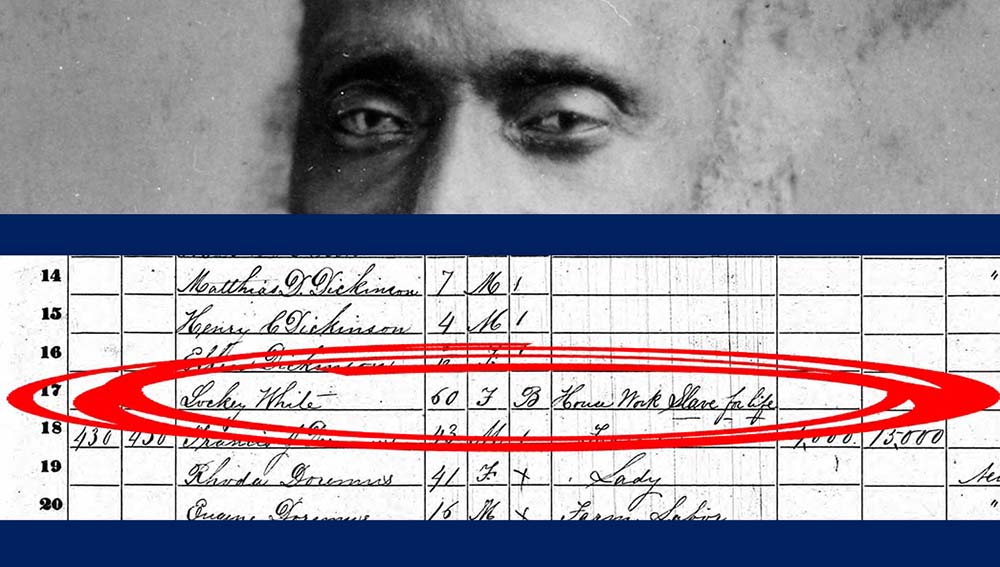

woodpusher quoting: "At the outbreak of the Civil War, New Jersey slaveholders owned eighteen apprentices for life—or, as the federal census more accurately classified them, “slaves.”

A Princeton professor, Albert B. Dod owned a slave as late as 1840, one of the last men in the state to do so."

Right, and while Northern states like New Jersey and Illinois gradually abolished slavery in accordance with our Founders' original intentions, in Southern states, the numbers of slaves increased 6-fold, from 654,121 in 1790 to 3,950,511 in 1860, while Southern agitations to increase legal protections for slavery never even slackened.

woodpusher: "Perhaps you should have tried reading my linked paper from Princeton University.

I know Princeton is not up to your usual Wikipedia standards, but some of us make do."

Well, two points on this:

- I'm not such a big fan of Princeton, seems to me they've always been a bit "off", even going back to the days when an aristocratic Son of the Confederacy, a very progressive Democrat named Woodrow Wilson, was Princeton's president.

- The quotes I truly treasure say the most with the fewest words, and nothing I've ever seen posted by woodpusher meets that criterion.

woodpusher:

"A lifetime apprenticeship of New Jersey differed so little from African slavery that the official census ignored the bullflop and listed them as what they really were — slaves." And so, turns out, the alleged official hypocrisy which has you so highly agitated, did not, in fact, exist -- actual slaves were counted as what they really were.

And, in the meantime, while New Jersey's slaves dwindled from 11,423 in 1790 to 18 in 1860, in the South, slaves increased 6-fold, from 654,121 in 1790 to 3,950,511 in 1860.

woodpusher: "Not one of your alleged court cases was linked, cited, or quoted.

It is very doubtful you even know what cases you are talking about, much less what is in them."

If you can prove me wrong here, I'll submit your proofs to Wikipedia and ask them to correct their mistakes.

woodpusher: "Of course, slaves in New Jersey, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri, not to mention Washington, D.C., are inconvenient facts."

Naw, that's just Lost Cause crazy-talk because, first of all, Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri and Washington, DC, were all slavery-legal with no laws restricting slavery and many laws supporting it.

New Jersey after 1804 was simply following the pattern previously set by Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Wisconsin.

Why that should so trigger your agitations is, frankly, a mystery to me.

woodpusher: "The fact that the 1860 census showed more free blacks in the slave states than in the free states gives the lie about the northern slaves having been set free.

They were not living as free men in the North.

They were sold South."

Naw, now you're just hallucinating.

Reality is that while Southern states grew numbers of slaves 6-fold by 1860, in northern states slave totals were reduced from 40,086 in 1790 to 18 in 1860, while the number of free-blacks grew 8-fold, from 27,034 in 1790 to 225,961 in 1860.

So, your whole idea that Northerners "hated blacks" and "sold them down the river" is just crazy-talk, projections from more typical Southern behaviors.

woodpusher: "Nonsense.

Cite the U.S. Supreme Court decision that did this.

Where did you cut and paste this crap from?

Let me guess.

Wikipedia?

On what legal basis did the Federal U.S. Supreme Court free any slaves in Indiana?

The fact is that you have no clue what you are talking about."

Wrong again, but unlike you, I do think there's a huge value to brevity and eliminating unnecessary words.

In this particular case, to quote exactly:

"Indiana -- the supreme court orders almost all slaves in the state to be freed in Polly v. Lasselle."

Polly v Lasselle was in Indian state court and was appealed to the Indiana Supreme court as State vs Lasselle, which ruled in 1820:

"The ruling was made on July 22, 1820,[1] based upon the Indiana Constitution, 11th article, section 7, 'There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

Nor shall any indenture of any negro or mulatto hereafter made, and executed out of the bounds of this state be of any validity within the state.'[6]"

The case was further appealed to the US Supreme Court, which refused to hear it, thus confirming the Indiana ruling.

![]()

105

posted on

07/10/2023 8:46:45 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(future DDG 134 -- we remember)

To: DiogenesLamp

You answered it and you're full of it.

The South would have maintained slavery for as long as it could where as the North ended it.

106

posted on

07/10/2023 8:47:48 AM PDT

by

jmacusa

(Liberals. Too stupid to be idiots.)

To: BroJoeK; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp

woodpusher: "You couldn't teach anybody anything unless it appears Wikipedia."

It's true that I don't try to depend on my own memory to keep the facts straight, and Wikipedia is a convenient source, mostly free and ad-free, of "common knowledge."

And unlike some younger people, I don't have access to whole electronic libraries full of useful data.

Maybe someday I'll figure out how they do that, but one problem is, we are already at the point of overloading with far too much information for the average person to absorb.

I'm not certain it helps arguments to load them down with very lengthy quotes from obscure sources...

By "common knowledge" you refer to what is often palpable nonsense. By my obscure sources, you refer to court documents fromm volumes by the court reporter, official government websites, and the like.

To find the official copy of the court opinion, and the draft of an appeal requires nothing more than a computer, a search engine, and the ability to use them.

Stating what is in court opinions without reading them, or making any attempt to do so, is just blatant ignorance.

Cite the U.S. Supreme Court decision that did this. Where did you cut and paste this crap from?

Let me guess.

Wikipedia?

On what legal basis did the Federal U.S. Supreme Court free any slaves in Indiana?

The fact is that you have no clue what you are talking about."

Wrong again, but unlike you, I do think there's a huge value to brevity and eliminating unnecessary words.

If I am wrong about you not knowing what you are talking about, cite, link, and/or quote the U.S. Supreme Court opinion that made the alleged claims.

You can always try to babble and bluster your way through, but you are too incompetent to do a google search and find even the State court opinion. I repeat for your enlightenment that it is at 1 Blackf. 60 (1820). There are no U.S. Supreme Court opinions in 1 Blackf.

You can continue to try to make believe reference to an unlinked and uncited State court opinion justifies the claim about a U.S. Supreme Court opinion, however, that only reveals the depth of your bullsplat.

woodpusher: "Not one of your alleged court cases was linked, cited, or quoted. It is very doubtful you even know what cases you are talking about, much less what is in them."

If you can prove me wrong here, I'll submit your proofs to Wikipedia and ask them to correct their mistakes.

What you admit is that you have never read the court opinions, and having been challenged, you are too lazy or incompetent to find them on the internet.

The claim that a U.S. Supreme Court opinion said what as claimed in 1820 is an absurdity on its face. No further proof is needed. It is quite tellling that not only did you make no attempt to find the non-existent Supreme Court opinion, but you have no idea of the correct citation for the State court opinion, no actual knowledge of its contents, and you have rather hilariously misstated even what Wikipedia or whoever may have said.

Now there is a load of horsecrap. As long as you are too lazy to find and read court opinions, you should stop making believe with your atttempts to shovel piles of steaming turds as some sort of research on your part. Maybe a picture will not overly strain your limited abilities.

300 N. Capitol Ave., Corydon, between the Harrison County Courthouse and the First State Capitol building (Harrison County, Indiana). Installed 2016 Indiana Historical Bureau, Harrison County Committee for the Indiana Bicentennial, and Leora Brown School.

"THIS DECISION DID NOT FREE REMAINING SLAVES IN INDIANA.

https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/find-historical-markers-by-county/indiana-historical-markers-by-county/polly-strong-slavery-case/

Strong appealed to Indiana Supreme Court in Corydon which ruled in State v. Lasselle, July 22, 1820: “slavery can have no existence” in Indiana. This decision did not free remaining slaves in Indiana; it did establish 1816 Indiana Constitution as the authority for decisions in Indiana courts regarding slavery and involuntary servitude, including 1821 Mary Clark case.

Who are we to believe? Numbnuts with Wikipedia and unnamed sources, or the Indiana Historical Bureau?

The correct citation for the State case is 1 Blackf. 60 (1820). The only reason you have not found it is that you are too lazy to look for it, or too incompetent to find it. Fortunately for me, I do not share your laziness or incompetence. But when you state some case says something, it is not my job to find the court opinions, or to tell you what they really say.

There is no citation to the U.S. Supreme Court. There is no indication that a petition for cert was ever drafted, filed or acted upon, and no indication of a docket number ever having been assigned. There is only evidence that the attorney drafted an appeal. The Appeal draft does not even read like a petition for cert which must precede any appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. There is no right of appeal of a case to the Supreme Court. One must obtain permission of the Court to file an appeal. The cert process obtains a Supreme Court docket number and a decision whether or not to consider the case.

Law Dictionary 2nd Ed., by Stephen H. Gifis:

CERTIORARI. Lat: to be informed of a means lf gaining appellate review; a common law writ issued from a superior court to one of inferior jurisdiction., commanding the latter to certify and return to the former the record in the particular case. 6 Cyr. 737. The writ is issued in order that the court issuing the writ may inspect the proceedings and determine whether there have been any irregularities. In the United StatesSupreme Court the writ is dicretionary with the Court and will be issued to any Court and will be to any court in the land to review a federal question if at least 4 of the 9 justices vote to hear the case. A similar writ used by some statecourts is called CERTIFICATION.

As is readily apparent, there must be a federal question placed to the Supreme Court. The highest court of a State is the ultimate authority in interpreting State law. An apppeal from the State court would normally be made first to the appropriate Circuit Court.

Should you, or anyone else, persist in a claim that this case was appealed to the Supreme Court, it is YOUR responsibility to produce some evidence that it happened.

Moreover, the crazy claim under review is:

in 1820 the US Supreme Court freed any slaves in Indiana

There was no case in the Supreme Court, and the case in the Indiana state court did NOT "free any slaves in Indiana." In context, any refers to any and all slaves remaining in Indiana, and does not refer to one or more slaves.

Strangely, the State monument states precisely the opposite. So you have a Supreme Court case that does not exist, and you have no court whatever that does what was claimed.

My response was:"...in 1845 Illinois supreme court freed any remaining indentured ex-slaves."

You have an innate ability for the irrelevant. We are discussing New Jersey which most definitely had slaves after the claimed end date of 1809. You constantly try to defend your child's nonsense with distracting nonsense of your own.

[jmacusa #53] "Slavery ended in NJ in 1809."

No it did not. And citing irrelevant events in Illinois changes nothing. Moreover, nothing challenges that Illinois replaced slavery with 99-year indentured servitude before it later abolished both.

In this particular case, to quote exactly:"Indiana -- the supreme court orders almost all slaves in the state to be freed in Polly v. Lasselle."

Polly v Lasselle was in Indian state court and was appealed to the Indiana Supreme court as State vs Lasselle, which ruled in 1820:

"The ruling was made on July 22, 1820,[1] based upon the Indiana Constitution, 11th article, section 7,

'There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

Nor shall any indenture of any negro or mulatto hereafter made, and executed out of the bounds of this state be of any validity within the state.'[6]"

As you provide neither link nor footnotes, the citations to footnotes are meaningless.

The paragraph from the STATE opinion quoting the Indiana Constitution, 11th Article, section 7 is accurate and appears at 1 Blackf. 62. Unfortunately, the next paragraph does not appear on any page of the Court's opinion.

What the actual opinion of the STATE Court says at 1 Blackf. 62:

In the 11th Article of that instrument, section 7th, it is declared, that "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this statem otherwise than for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." It is evident that, by these provisions, the framers of our constitution intended a total and entire prohibition of slavery in this state; and we can conceive of no form of words in which that intention could have been more clearly expressed.

While you provide no link to your source, or its footnoted source, the footnoted source is an article by Sandra Boyd Williams at Ind. L. Rev. 30:305 which provides the same quote as I did, albeit without the italicized emphasis appearing in the official Reporter copy. While a Wikipedia legal meathead attributes the paragraph about "any negro or mulatto" to the Williams article, that paragraph is not to be found therein.

Wikipedia: "Lasselle filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of the United States on July 27, 1820." This load of crap is not just wrong but impossible for 1820. The court opinion was handed down on Saturday, July 22, 1820. The draft Appeal is dated July 27, 1820. And for this load of crap to be accurate, on the day the document was drafted in Indiana, it was also filed in the U.S. Supreme Court. I doubt they had electronic filing in 1820.

Right, and before the 1857 SCOTUS Dred Scott ruling, such practices were often disciplined by state courts, even in the South, who recognized Northern states' laws automatically manumitting slaves who were kept too long in a Northern state. Those are the grounds on which Dred Scott sued for his freedom and which SCOTUS Chief Crazy Roger Taney struck down in his insane opinions.

In point of fact, Chief Justice Taney did not, and could not, strike down anuything with his opinions. Only Opinions of the Court do that. For any stated opinion to rise above the level of dicta, and have legal effect, it must be supported by a majority of the justices; in the case of Scott, that being five. It must also be necessary to resolve the issue before the court. Extremely little in Taney's opinion was so supported. All nine opinions must be read to sort out what the Court opined. As you do not read court opinions, you only blather about them, once again, you do not know what you are talking about.

The crazy manufactured plea of Dred Scott was properly shot down by showing a lack of standing on the part of Scott and a lack of jurisdiction on the part of the Court. The case was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction on the part of the U.S. Supreme Court and remanded to the lower court with instructions to dismiss the case for lack of jurisdiction in that court.

Scott's claim to federal jurisdiction was made on a claim of diversity of state citizenship, with Scott claiming to be a citizen of Missouri, and claiming the defendant Sanford was a citizen of New York. In previous litigation, the Supreme Court of Missouri determined that Scott was not a citizen of Missouri according to Missouri law. The highest court of a state is the ultimate authority in interpreting state law. Absent citizenship in the state of Missouri, pursuant to the laws of Missouri, Scott had no claim to invoke the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

Scott claimed that Sanford purhased him directly from Dr. John Emerson about ten years after Emerson died. The real owner was a Massachusetts abolitionist congressman, Calvin Chaffee, husband of Elizabeth Irene Sanford Emerson Chaffee who was the owner of Scott before her husband became the owner.

While the litigation was pending for years, Dred Scott was in the custody of a sheriff who hired him out and put the earnings in escrow. When the case was decided, Mrs. Chaffee claimed the funds in escrow. Congressman Chaffee of Massachusetts executed a quitclaim deed to transfer his ownership of Scott.

Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1857) was decided March 6, 1857. In May 1857, Massachusetts Congressman Calvin Chaffee executed a quitclaim deed in favor of Taylor Blow in Missouri giving Blow ownership of Dred Scott and family. The ownership story had hit the major newspapers. On May 26, 1857 Taylor Blow emancipated the Scotts.

26 Saint Louis Circuit Court Record 2631

Tuesday May 26th 1857 Taylor Blow, who is personally known to the court, comes into open court, and acknowledges the execution by him of a Deed of Emancipation to his slaves, Dred Scott, aged about forty eight years, of full negro blood and color, and Harriet Scott wife of said Dred, aged thirty nine years, also of full negro blood & color, and Eliza Scott a daughter of said Dred & Harriet, aged nineteen years of full negro color, and Lizzy Scott, also a daughter of said Dred & Harriet, aged ten years likewise of full negro blood & color.

1 26 Saint Louis Circuit Record 263

The next day, Eliza Irene Sanford Emerson Chaffee’s attorney filed the motion to claim all of the wages earned by Scott, held by the Sheriff.

26 Saint Louis Circuit Court Record 2671

Wednesday May 27th 1857

Dred Scott.

vs. )

Irene Emerson. ) On motion of defendants attorney it is ordered that the Sheriff of St. Louis County do render his account to the court of the wages that have come to his hands of the earnings of the above named plaintiff and that the said sheriff do pay to the defendant all such wages that now remain in his hands, excepting all commissions and expenses to which the said Sheriff may be legally entitled.

1 26 Saint Louis Circuit Record 267

To: woodpusher; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp; x; jeffersondem

First, we should remember how jeffersondem deals with a lengthy post, when he disagrees with it.

And I'll point out that I've not done that with woodpusher's lengthy posts, though the thought did occur to me.

woodpusher: "By "common knowledge" you refer to what is often palpable nonsense.

By my obscure sources, you refer to court documents from volumes by the court reporter, official government websites, and the like."

Well... first, anything can be "palpable nonsense" if it's misused, for example, in claiming that a legitimate quote supports a spurious argument, when if fact it does not.

So, it's not facts which can be "nonsense", but rather the uses to which facts are employed.

Second, as for "common knowledge", I'm mainly referring to keeping names, dates, other numbers and known quotes straight.

Where Wikipedia delves into analyses, they usually give both sides, though the seemingly stronger case will be the one which has more of "common knowledge".

Third... well, in some cases, "obscure sources" means actual fake quotes, which we don't see as much of these days as we used to -- it's too easy now to fact-check them.

In other cases, "obscure sources" is not the best term for what I'm thinking of for you, woodpusher, namely: in too many cases you post lengthy quotes which either do not say what you claim they say, or they support points which are irrelevant to what's being discussed.

woodpusher: "Stating what is in court opinions without reading them, or making any attempt to do so, is just blatant ignorance."

The truth is, there can be a lot of "blatant ignorance" on display here, even by some who claim to have read whole libraries full of legal opinions.

This will become apparent in the particulars of examples we're talking about here.

woodpusher: "If I am wrong about you not knowing what you are talking about, cite, link, and/or quote the U.S. Supreme Court opinion that made the alleged claims."

And here is a good example of you doubling down on "blatant ignorance", by refusing to acknowledge the truth of the matter while wildly clinging to distinctions which don't matter.

In this example, there were three courts involved:

- A local Indiana state court ruled on Polly v Lasselle, 1820.

- Indiana's state supreme court overturned that ruling in State vs. Lasselle, still 1820.

- The US Supreme Court refused to hear the case, thus confirming the state supreme court's decision, still in 1820.

So what matters in all this is what Indiana's state supreme court said, as confirmed by the US Supreme Court.

Here I posted quotes which sound to me like blanket, bullet-proof abolition in Indiana.

So you, woodpusher, point out, potentially correctly, that Indiana's legal seals against slavery still did not 100% stop all slavery.

So, I say, without even delving into the merits of your ridiculous arguments, let's look at the actual results, OK?

- In 1820 Virginia had 420,153 slaves

- In 1820 Indiana had 190 slaves (not 190,000, just 190)

- By 1850, Virginia's slaves grew to 472,528 = 11% increase, despite massive numbers sold into Deep South states.

- By 1850, Indiana had zero slaves, whatever loopholes there may have been in Indiana's laws, the result was zero slaves.

So, while Virginia added 52,375

more slaves, Indiana reduced its slave population to zero, and yet in woodpusher's warped demented Democrat mind, Virginia had the moral high ground and Indianans should grovel in shame!

This is why it doesn't matter how many legal cases you quote or how lengthy the quotes, your argument here is still total BS.

woodpusher: "What you admit is that you have never read the court opinions, and having been challenged, you are too lazy or incompetent to find them on the internet."

Because all that is 100% irrelevant to the questions which matter here, namely, were Indiana's abolition laws strong enough to gradually abolish slavery?

The answer is, as proved by US census numbers: of course they were, in 10 years Indiana's laws reduced slaves from 190 to 3 and in 20 more years to zero.

In the meantime, the number of freed-blacks in Indiana grew from 1,230 in 1820 (6 times the number of slaves) to 11,262 in 1850 (with zero slaves).

Only a raging partisan Democrat could look at such numbers and still claim there was something wrong in Indiana, compared to any Southern state.

woodpusher: "Now there is a load of horsecrap.

As long as you are too lazy to find and read court opinions, you should stop making believe with your atttempts to shovel piles of steaming turds as some sort of research on your part.

Maybe a picture will not overly strain your limited abilities."

I'll restate it: all the lengthy opinions in the world, in this particular case, are 100% irrelevant to the main conclusion, which is that Indiana's abolition laws were 100% adequate to do what they were intended to do, which was to gradually abolish slavery, in their case, from 190 slaves in 1820 to zero in 1850.

Everything else is just you blowing smoke to obscure the facts.

quoting jmacusa: "Slavery ended in NJ in 1809."

woodpusher: "No it did not."

New Jersey's 1804 gradual abolition law reduced numbers of slaves from:

- 1800 -- 12,242

- 1810 -- 10,851

- 1820 -- 7,757

- 1850 -- 236

In the meantime, New Jersey's freed-blacks grew from:

- 1800 -- 4,402

- 1810 -- 7,803

- 1820 -- 12,460

- 1850 -- 23,810

So, New Jersey's abolition laws did what they were intended to do. Your claims otherwise are pure nonsense.

woodpusher: "In point of fact, Chief Justice Taney did not, and could not, strike down anuything with his opinions. "

Naw, all you're doing here is making useless lawyerly quibbles to obscure the fact that you're arguing complete nonsense.

The fact is that Roger Taney was a raging lunatic whose SCOTUS opinions were highly influential in giving Southern Democrats what they wanted in 1857, while motivating Northerns to organize as anti-slavery Republicans against Crazy Roger's expansions of "slavers' rights".

Nobody said it better than Lincoln himself:

"We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State."

1858 House Divided Speech

This fear of Crazy Roger helped elect Lincoln president in 1860, regardless of how much you wish to quibble, split hairs and lawyerly sharpshoot what, exactly, Crazy Roger actually said.

![]()

108

posted on

07/11/2023 7:08:37 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(future DDG 134 -- we remember)

To: BroJoeK; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp; jeffersondem

woodpusher: "Stating what is in court opinions without reading them, or making any attempt to do so, is just blatant ignorance."

The truth is, there can be a lot of "blatant ignorance" on display here, even by some who claim to have read whole libraries full of legal opinions.

This will become apparent in the particulars of examples we're talking about here.

An abject example of saying nothing while avoiding the obvious evidence of prior ignorance.

in 1820 the US Supreme Court freed any slaves in Indiana

In reply are citations to STATE court opinions which did NOT free any slaves in Indiana.

300 N. Capitol Ave., Corydon, between the Harrison County Courthouse and the First State Capitol building (Harrison County, Indiana). Installed 2016 Indiana Historical Bureau, Harrison County Committee for the Indiana Bicentennial, and Leora Brown School.

"THIS DECISION DID NOT FREE REMAINING SLAVES IN INDIANA.

woodpusher: "If I am wrong about you not knowing what you are talking about, cite, link, and/or quote the U.S. Supreme Court opinion that made the alleged claims."

And here is a good example of you doubling down on "blatant ignorance", by refusing to acknowledge the truth of the matter while wildly clinging to distinctions which don't matter.

In this example, there were three courts involved:

A local Indiana state court ruled on Polly v Lasselle, 1820.

Indiana's state supreme court overturned that ruling in State vs. Lasselle, still 1820.

The Polly case was never a U.S. Supreme Court case. Citing State cases cannot support a claim that the U.S. Supreme Court issued any ruling.

The request to provide a cite, link or quote of any U.S. Supreme Court case is just avoided because there is no such case. Nor can BroJoeK cite to any Petition for a Writ of Cert requesting permission to file an appeal in the Polly case. Nor can BroJoeK provide a scintilla of evidence that any U.S. Supreme Court docket number was ever assigned to the Polly case. Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court never has refused to hear a case. To each petition for writ of cert, the Court issues an order accepting or denying the Petition. However, in the instant case, there is no Petition, no docket number, and no order denying the non-existent Petition.

There was a draft of an Appeal discovered in the papers of the attorney, dated July 27, 1820. There is also an unsupported and unsupportable claim by an anonymous source that an appeal was filed on July 27, 1820. The impossibility of the claim is self-evident. Consider drafting an Appeal in Indiana in 1820 and filing it with the Court in Washington D.C. the same day. It would seem the only question left is whether the attorney flew first class or took a private jet.

The US Supreme Court refused to hear the case, thus confirming the state supreme court's decision, still in 1820.

Jerome A. Barron and C. Thomas Dienes, Constitutional Law, Thomson West 2003, Sixth Edition, Black Letter Series, West Group, page 72-3:

c. Discretionary Review 1) Certiorari

With a few minor exceptions, Supreme Court review of lower court decisions is discretionary. The losing party below petitions the Court of a writ of certiorari. Certiorari is granted when four justices vote to review the decision (the Rule of Four). A denial of certiorari is not a decision on the merits.

Black's Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, 1990, p. 1609:

Writ of certiorari. [...]

In the U.S. Supreme Court, a review on writ of certiorari is not a matter of right, but of judicial discretion, and will be granted only when there are special and important reasons therefor. 28 U.S.C.A. §§ 1254, 1257; Sup.Ct.Rules 10 et seq.

So what matters in all this is what Indiana's state supreme court said, as confirmed by the US Supreme Court.

The U.S. Supreme Court case does not exist, and BroJoe is unable to kink, cite, or quote the imaginary case. Neither does the U.S. Supreme Court order issuing its "refusal" to hear the case. The U.S. Supreme Court did not say a damned thing, nor can BroJoe quote them saying a damn thing.

As for what BroJoe says the Indiana Supreme Court said, Indiana has erected a monument stating the Court said exactly the opposite, BroJoe just leaving out the word "not."

By 1850, Indiana had zero slaves, whatever loopholes there may have been in Indiana's laws, the result was zero slaves.

We are not talking about the state of Indiana in 1850. Nor are we talking about your other diversionary, irrelevant bullflop.

woodpusher: "In point of fact, Chief Justice Taney did not, and could not, strike down anything with his opinions. "

Naw, all you're doing here is making useless lawyerly quibbles to obscure the fact that you're arguing complete nonsense.

The fact is that Roger Taney was a raging lunatic whose SCOTUS opinions were highly influential in giving Southern Democrats what they wanted in 1857, while motivating Northerns to organize as anti-slavery Republicans against Crazy Roger's expansions of "slavers' rights".

As the mandate issued to the Circuit Court in the case of Scott v. Sandford shows, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the Circuit Court had no jurisdiction to hear the case, and remanded the case to that court with instructions to dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction.

Missouri, C.C.U.S. No. 7

Dred Scott, Ptff. in Er.

vs.

John F.A. Sandford

Filed 30th December 1854.

Dismissed for want of jurisdiction.

March 6th, 1857. —

- - - - - - - - - -

No. 7

Ptff. in Er.

Dred Scott

vs.

John F.A. Sandford

In error to the Circuit Court of the United Stated for the District of Missouri.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the record from the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Missouri and was argued by counsel. On consideration whereof, it is now here ordered and adjudged by this court that the judgment of the said Circuit Court in this cause be and the same is hereby reversed for the want of jurisdiction in that court and that this cause be and the same is hereby remanded to the said Circuit Court with directions to dismiss the case for the want of jurisdiction in that court. —

Ch. Jus. Taney

6th March 1857

Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case, Its Significance in American Law and Politics, 2001, p. 324, provides a box score of results as follows:

1. Four justices held that the plea in abatement was properly before the Court (Taney, Wayne, Daniel, and Curtis). 2. Three justices held that a Negro could not be a citizen of the United States (Taney, Wayne, and Daniel).

3. Six justices held that the Missouri Compromise restriction was invalid (Taney, Wayne, Grier, Daniel, Campbell, and Catron).

4. Seven justices held that the laws of Missouri determined Scott's status as a slave after his return to that state from Illinois (Taney, Wayne, Nelson, Grier, Daniel, Campbell,, and Catron).

5. Seven justices held that Scott was still a slave, though there were differences of what the final judgment of the Court should be (same as in number 4).

Only a majority of justices form an Opinion of the Court. There was neither a holding of the Court that a Negro could not be a citizen, nor a holding of the Court that the plea in abatement was properly before the Court. As these were never adopted as Opinions of the Court, discussing them as such is fantasy land. That Taney’s opinion was captioned Opinion of the Court does not make everything in it an opinion of the Court.

There were holdings of the Court that the Missouri Compromise was invalid; that Missouri law determined Scott's status as a slave after his return to Missouri; and that Scott was still a slave.

BroJoeK #105 Right, and before the 1857 SCOTUS Dred Scott ruling, such practices were often disciplined by state courts, even in the South, who recognized Northern states' laws automatically manumitting slaves who were kept too long in a Northern state.

The is total make-believe bullflop. No law ever automatically manumitted anyone, from Somersett to Scott.

A slave taken to a free state, while in that free state, might successfully sue for his freedom, but should he return to a slave state, he resumed his status as a slave. This was upheld in English as well as American law. There is ample precedent to support the holdings of the Court. One cannot ignore the precedents set in R. v. Knowles ex rel Somersett, (1772) 20 State Tr 1, (aka Somerset v Steuart); The Slave, Grace, 2 Hagg. 94 (1833); Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82 (1851); and Lemmon v. The People, 20 N.Y. 562 (1860)

In the case of Lemmon v. The People,

The Lemmons were Virginia slaveholders moving to Texas. The fastest route, although hardly the most direct, was to take a boat from Norfolk to New York City and then change for a ship that was heading for New Orleans. In 1852 they came to New York with their eight slaves. While they were there, a black dockworker obtained a writ of habeas corpus and a local judge ruled that under New York law the "eight colored Virginians," as the judge called them, became free the moment their owner brought them into the state. This decision was consistent with precedents dating from the Somerset case (1772). In 1857 a middle-level New York court upheld the Lemmon decision, but in the aftermath of Dred Scott the state of Virginia appealed the decision to New York's highest court, the Court of Appeals. In 1860 that court also upheld the original ruling in favor of freedom.

SOURCE: Dred Scott v. Sandford, A brief History with Documents, Paul Finkelman, (1997), p. 47.

The case was not appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The referenced Somerset case is a British case, Somerset v. Stewart, 1 Lofft (G.B.) 1, (1772).

In Somerset Lord Mansfield, chief justice of the Court of King's Bench, declared:

So high an act of dominion [as enslavement of a human being] must be recognized by the law of the country where it is used.... The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political;... it's so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law.

However, in speaking of the Somerset rule, one must also consider the case of The Slave, Grace, 2 Hagg. Admir. (G.B.) 94, (1827)

In The Slave, Grace (1827), the English High Court of Admiralty modified the Somerset rule. Grace, a West Indian slave, had been taken to England but then returned to Antigua with her master. She sued for her freedom only after returning to Antigua. Lord Stowell, speaking for the English court, held that Grace was still a slave. Stowell found that residence in England only suspended the status of a slave. Without positive law, the master could not control a slave in England and could not force a slave to leave the realm. But if a slave did return to a slave jurisdiction, as Grace had, then the law of England would no longer be in force and the person's status would once again be determined by the laws of the slave jurisdiction.

SOURCE: Dred Scott v. Sandford, A brief History with Documents, Paul Finkelman, (1997), p. 21.

Also consistent is the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82 (1851)

At 93-94:

Every state has an undoubted right to determine the status, or domestic and social condition of the persons domiciled within its territory except insofar as the powers of the states in this respect are restrained, or duties and obligations imposed upon them, by the Constitution of the United States. There is nothing in the Constitution of the United States that can in any degree control the law of Kentucky upon this subject. And the condition of the negroes, therefore, as to freedom or slavery after their return depended altogether upon the laws of that state, and could not be influenced by the laws of Ohio. It was exclusively in the power of Kentucky to determine for itself whether their employment in another state should or should not make them free on their return. The Court of Appeals has determined that by the laws of the state, they continued to be slaves. And their judgment upon this point is, upon this writ of error, conclusive upon this Court, and we have no jurisdiction over it.

Upon the return of Etheldred Scott to Missouri, the laws of the state of Missouri operated upon him, and those alone determined his status. The Supreme Court of Missouri found that, under the laws of Missouri, Scott was a slave,

The U.S. Supreme Court concurred that the deciding law was the law of Missouri, and that the holding in the prior case of Scott v. Emerson, a case separate from Scott v. Sandford, was decisive and not appealed. Scott was a slave and, as such, could not use diversity of state citizenship to invoke the jurisdiction of the federal courts. There being no jurisdiction of the Circuit Court to have heard or decided the case, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Circuit Court with instructions to dismiss for want of jurisdiction.

As previously stated, only opinions by a majority are opinions of the Court. The Scott case was originally assigned to Justice Nelson to write the opinion of the Court. His opinion is fairly short and to the point. However, it became known that Justice Curtis intended to write a very long dissenting opinion raising many of the issues the Court had avoided, especially negro citizenship and the validity of the Missouri Compromise. Justice Wayne suggested that the Chief Justice write an opinion responding to unnecessary dicta, and that said opinion be captioned as the Opinion of the Court. Curtis went on to leak his magnum opus to the press before any official opinion on the case was officially released. Taney took up the challenge to write an opinion with page after page of dicta responding to the dicta of Justice Curtis.

Justice Curtis was the youngest justice on the Court. He never again sat on the Court, but resigned before the next session. Not only was the true owner of Dred Scott from Massachusetts, Justice Curtis was from Massachusetts. Not only were they both from Massachusetts but the noted lawyer who argued the constitutional issues for Scott was also from Massachusetts. Not only was that lawyer from Massachusetts, he was George Curtis, the elder brother of Justice Benjamin Curtis, who saw no reason for recusal.

As most of what was in the magnum opus of Justice Curtis was not properly before the court, here are a few more.

John Sanford was not a real party to the case. While the parties mutually agreed to a purported Statement of Facts, this included a fictitious sale of Dred Scott by a then long-dead Dr. Emerson to John Sanford. Mrs. Emerson remarried in 1850 and, under the law of femes covert, married women did not own property. Rather, Congressman Chaffee was the new owner of Dred Scott, and the person who should have been the properly named defendant in the case. It was Congressman Chaffee who bestowed Dred Scott to Taylor Blow of Missouri via quit-claim deed right after the decision; and it was Taylor Blow who manumitted Dred Scott in Missouri. Mrs. Chaffee did claim the wages of Dred Scott being held by the Sheriff. John Sanford had died in an insane asylum. The false claim of ownership had been made to fashion a bogus claim of jurisdiction via diversity of state citizenship without implicating a sitting Massachusetts congressman.

To: woodpusher; x; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp; jeffersondem

woodpusher:

"An abject example of saying nothing while avoiding the obvious evidence of prior ignorance." And yet... "prior ignorance" is not the issue here, it's a distraction, it's just woodpusher blowing smoke to avoid admitting the obvious, which is that Northern states like Indiana, New Jersey and Illinois all gradually abolished slavery, while in the South slave populations only increased, and no efforts were made to even restrict, much less abolish slavery there.

quoting BJK: "in 1820 the US Supreme Court freed any slaves in Indiana"

woodpusher: "In reply are citations to STATE court opinions which did NOT free any slaves in Indiana."

I can see, you've made a minor distinction, and blown it up beyond any merit.

More accurately stated: in 1820 the US Supreme Court confirmed Indiana laws and rulings which eventually reduced it's slave population from 190 to zero.

The fact remains that Indiana, and others, abolished slavery while no Southern state even seriously restricted it.

woodpusher: "The Polly case was never a U.S. Supreme Court case.

Citing State cases cannot support a claim that the U.S. Supreme Court issued any ruling."

Here again is the wording from that Wikipedia article on Polly Strong:

"The ruling was made on July 22, 1820,[1] based upon the Indiana Constitution, 11th article, section 7,'There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

Nor shall any indenture of any negro or mulatto hereafter made, and executed out of the bounds of this state be of any validity within the state.'[6]

Justice James Scott wrote, 'It is evident that by these provisions, the framers of our constitution intended a total and entire prohibition of slavery in this State; and we can conceive of no form of words in which that intention could have been more clearly expressed.'[6]

Strong was declared a free woman.[8]

Lasselle filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of the United States on July 27, 1820.

The court refused to hear the case, upholding the decision made by the Indiana Supreme Court.[9]"

So, now you, woodpusher, tell us you personally can't find evidence of Lasselle's alleged July 27, 1820 appeal and therefore it was never really made.

I'd say, your personal inability to find evidence may indeed suggest something, though exactly what is still an open question.

Possibilities include, did Lasselle claim he'd submitted an appeal when in fact he never did, or maybe, given 1820 travel conditions, the appeal didn't make it all the way to Washington, or having reached Washington, was it informally side-tracked rather than formally refused?

Or, perhaps it's just that woodpusher's research skills are not quite as awesome as he likes to pretend?

And none of these possibilities changes one iota the fact that Indiana's abolition laws and rulings did gradually reduce slaves from 190 in 1820 to zero by 1850.

woodpusher: "Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court never has refused to hear a case.

To each petition for writ of cert, the Court issues an order accepting or denying the Petition."

Now there is a great lawyerly distinction which I'm certain makes a huge difference to... well... ah... nobody outside a law classroom.

woodpusher: "There was a draft of an Appeal discovered in the papers of the attorney, dated July 27, 1820.

There is also an unsupported and unsupportable claim by an anonymous source that an appeal was filed on July 27, 1820. "

Oh look, I guessed right, somebody claimed Lasalle appealed.

woodpusher: " It would seem the only question left is whether the attorney flew first class or took a private jet."

Or, maybe he was already in Washington at the time and just "flew" across the street...

woodpusher quoting: "A denial of certiorari is not a decision on the merits."

And yet... it still has the effect of confirming a lower court's rulings.

Funny how that works.

woodpusher: "The U.S. Supreme Court case does not exist, and BroJoe is unable to kink, cite, or quote the imaginary case.

Neither does the U.S.

Supreme Court order issuing its "refusal" to hear the case.

The U.S. Supreme Court did not say a damned thing, nor can BroJoe quote them saying a damn thing."

And so, amazingly, despite all of woodpusher's lawyerly smoke-blowing, the lower court ruling stood confirmed as the law in Indiana, and slavery was gradually abolished there.

woodpusher: "As for what BroJoe says the Indiana Supreme Court said, Indiana has erected a monument stating the Court said exactly the opposite, BroJoe just leaving out the word "not.""

The Indiana court's words quoted above seem pretty clear, to repeat them here:

"There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

Nor shall any indenture of any negro or mulatto hereafter made, and executed out of the bounds of this state be of any validity within the state.'"

So, woodpusher keeps telling us, over and over, that this quote is invalid, and yet has provided no evidence of that.

Why would anyone believe it?

woodpusher: "We are not talking about the state of Indiana in 1850.

Nor are we talking about your other diversionary, irrelevant bullflop."

That is the only thing we're talking about -- that Indiana gradually abolished slavery.

Every other point you've raised here is 100% lawyerly BS smoke-screen intended only to obscure the fundamental facts.

woodpusher: "Only a majority of justices form an Opinion of the Court.

There was neither a holding of the Court that a Negro could not be a citizen, nor a holding of the Court that the plea in abatement was properly before the Court.

As these were never adopted as Opinions of the Court, discussing them as such is fantasy land.

That Taney’s opinion was captioned Opinion of the Court does not make everything in it an opinion of the Court."

The vote was 7-2, an absolute Southern dominated majority.

Crazy Roger's insane opinions laid the groundwork for the next such SCOTUS ruling which, as Lincoln observed, would turn Northern states in slave states.

That's what turned many pro-Southern Northern Democrats into anti-slavery Northern Republicans and helped elect Lincoln president in 1860.

woodpusher: "The is total make-believe bullflop.

No law ever automatically manumitted anyone, from Somersett to Scott."

Well, you can quibble over the word "automatically", but the most famous example is Pres. Washington, living in Philadelphia during Pennsylvania's gradual abolition period.

Pennsylvania law required, in effect, that Washington rotate his slaves in Philadelphia after a certain defined time-period, or they would be subject to legally imposed manumission.

Here are cases more directly related to Dred Scott:

- "It was expected that the Scotts would win their freedom with relative ease.[21][24]: 241

By 1846, dozens of freedom suits had been won in Missouri by former slaves.[24]

Most had claimed their legal right to freedom on the basis that they, or their mothers, had previously lived in free states or territories.[24] - Among the most important legal precedents were Winny v. Whitesides[25] and Rachel v. Walker.[26]

- In Winny v. Whitesides, the Missouri Supreme Court had ruled in 1824 that a person who had been held as a slave in Illinois, where slavery was illegal, and then brought to Missouri, was free by virtue of residence in a free state.[23]: 41

- In Rachel v. Walker, the state supreme court had ruled that a U.S. Army officer who took a slave to a military post in a territory where slavery was prohibited and retained her there for several years, had thereby "forfeit[ed] his property".[23]: 42

Rachel, like Dred Scott, had accompanied her enslaver to Fort Snelling.[23]"

woodpusher: "A slave taken to a free state, while in that free state, might successfully sue for his freedom, but should he return to a slave state, he resumed his status as a slave.

This was upheld in English as well as American law. "

Not true, see examples cited above.

woodpusher quoting: "...local [New York] judge ruled that under New York law the "eight colored Virginians," as the judge called them, became free the moment their owner brought them into the state.

This decision was consistent with precedents dating from the Somerset case (1772)."

So, it appears that you agree with me on this point, or did you not actually read your own quote?

woodpusher quoting on the 1827 British ruling: "Without positive law, the master could not control a slave in England and could not force a slave to leave the realm.

But if a slave did return to a slave jurisdiction, as Grace had, then the law of England would no longer be in force and the person's status would once again be determined by the laws of the slave jurisdiction."

So it appears that different courts, in this case a British court, ruled different ways on this matter.

The US, we might say, was more "slave-friendly".

woodpusher: "Not only was that lawyer from Massachusetts, he was George Curtis, the elder brother of Justice Benjamin Curtis, who saw no reason for recusal."

So, had Justice Curtis recused himself, the vote on Dred Scott would be, instead of 7-2, 7-1 a near unanimous display of Southern control over the 1857 US Supreme Court, thus even more strongly supporting Northern fears that the US Supreme Court was only one decision away from imposing slavery on Northern states.

![]()

110

posted on

07/12/2023 6:12:50 AM PDT

by

BroJoeK

(future DDG 134 -- we remember)

To: BroJoeK; woodpusher; x; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp; jeffersondem

Possibilities include, did Lasselle claim he'd submitted an appeal when in fact he never did, or maybe, given 1820 travel conditions, the appeal didn't make it all the way to Washington, or having reached Washington, was it informally side-tracked rather than formally refused? Or, perhaps it's just that woodpusher's research skills are not quite as awesome as he likes to pretend? I think the overall thrust of woodpusher's point is that the Wikipedia article you keep citing (instead of primary sources like woodpusher is doing) outright states "Lasselle filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of the United States on July 27, 1820.". This is not a claim of no appeal having been submitted, or that it didn't make it to Washington, or that it got informally rejected; this is a direct claim that an appeal *was made* to the SCOTUS. Such an appeal would have a paper trail documenting its existence with the SCOTUS.

Now, if the draft of an appeal dated 7/27/1820 was in the effects of Hyacinthe Laselle (living in Indiana), then it was impossible for said appeal to have been made to the SCOTUS on 7/27/1820 as Wikipedia claims.

Note that this was before the invention of the telegraph, so the only way such an appeal could have been delivered to the SCOTUS was either in person or by mail.

Even if Hyacinthe had booked it the MOMENT the case ended on 7/22, and drafted his appeal on the way, it was not possible to get to Washington D.C. from Indiana in 5 days; note that it would be over 15 years until the first railroad tracks were laid in Indiana, so he would have had to travel by foot.

Maybe he was actually a world-class sprinter/marathon runner.

111

posted on

07/12/2023 12:51:39 PM PDT

by

Ultra Sonic 007

(There is nothing new under the sun.)

To: BroJoeK; jmacusa; DiogenesLamp; jeffersondem; Ultra Sonic 007

Northern states like Indiana, New Jersey and Illinois all gradually abolished slavery,

Nobody but a simple minded moron, such as yourself, would even consider arguing that any one of the states did not eventually abolish slavery. The case in point was the claim of jmacusa that the state of New Jersey aboished slavery in 1809. No measure of your obfuscatory bullflop can change the fact that New Jersey did not abolish slavery in 1809. As for the intent of gradual emancipation....

Inspired directly by God, Thomas Jefferson espoused gradual emancipation. And while so inspired, Thomas wrote down for posterity that such holy emancipation was to be a precursor for deportation of the Black population, and that their place was to be filled up by free white laborers.

Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson

Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [Blacks] are to be free. Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government. Nature, habit, opinion has drawn indelible lines of distinction between them. It is still in our power to direct the process of emancipation, and deportation, peaceably, and in such slow degrees, as that the evil will wear off insensibly; and their places be, pari passu, filled up by free white laborers.

And did the Great Emancipator not give the original NIMBY assurance to the nation?

But it is dreaded that the freed people will swarm forth, and cover the whole land? Are they not already in the land? Will liberation make them any more numerous? Equally distributed among the whites of the whole country, and there would be but one colored to seven whites. Could the one, in any way, greatly disturb the seven? There are many communities now, having more than one free colored person, to seven whites; and this, without any apparent consciousness of evil from it. The District of Columbia, and the States of Maryland and Delaware, are all in this condition. The District has more than one free colored to six whites; and yet, in its frequent petitions to Congress, I believe it has never presented the presence of free colored persons as one of its grievances. But why should emancipation south, send the free people north? People, of any color, seldom run, unless there be something to run from. Heretofore colored people, to some extent, have fled north from bondage; and now, perhaps, from both bondage and destitution. But if gradual emancipation and deportation be adopted, they will have neither to flee from. Their old masters will give them wages at least until new laborers can be procured; and the freed men, in turn, will gladly give their labor for the wages, till new homes can be found for them, in congenial climes, and with people of their own blood and race. This proposition can be trusted on the mutual interests involved. And, in any event, cannot the north decide for itself, whether to receive them?

As subsequently and approvingly quoted by Abraham Lincoln in his famous Cooper Union address, New York City, February 27, 1860:

Collected Works, Vol. III, pg. 541

Indiana and Illinois are not New Jersey.

Enough states ratified the 13th Amendment that it was certified and became part of the Constitution in 1865, over the objections of New Jersey. New Jersey finally saw the light in 1866 and ratified the 13th Amendment. That brought about their sudden abolishment of slavery.

quoting BJK: "in 1820 the US Supreme Court freed any slaves in Indiana"

No, moron. Not quoting BJK. Quoting jmacusa #53. You joined the conversation late, did not bother to read the thread, and proceeded to spam, not knowing what you were spammig about.

https://freerepublic.com/focus/chat/4165496/posts?page=53#53

Slavery ended in NJ in 1809. … 53 posted on 7/8/2023, 3:40:20 PM by jmacusa

You didn't say it. I should't have to tell you that you didn't say it.

As a matter of historical fact, stated officially by the state of New Jersey, slavery was the last state to end slavery in 1866.

That Taney’s opinion was captioned Opinion of the Court does not make everything in it an opinion of the Court."

The vote was 7-2, an absolute Southern dominated majority.

The decision was 7-2, idiot. The decision, as stated in the mandate, was to dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction. You seem to be too legally incompetent to distinguish between the Opinion and the Decision.

FOUR justices were from what were to become Confederate states, FIVE justices were from what were Union states during the Civil War.

Justice Curtis was from Massachusetts

Justice Nelson was from New York.

Justice McLean was from New Jesey.

Justice Grier was from Pennsylvania.

CJ Taney was from Maryland.

Justice Wayne was from Georgia.

Justice Daniel was from Virginia.

Justice Campbell was from Alabama.

Justice Catron was from Tennessee.

Even if one counts CJ Taney from the Union state of Maryland as part of your "Southern dominated majority," there were still four distictly Northern justices, from Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

Notably, you do not argue the merits because you have no argument to make. In Scott v. Emerson (1852). As the Supreme Cout noted in Scott v. Sandford, that case was never appealed to the Supreme Court, and was final.

As the Supreme Court of Missouri in the Emerson case of 1852 decided Scott's citizenship status in Missouri, no prior case from that court, or any lower court, was thereafter citable as authority. The law of no other state is cited as controlling in Missouri.

Crazy Roger's insane opinion

Please do cite your insane opinion of something Taney stated as being insane, or even contrary to law. I understand your reticence to state anythig specific because is is easier to hide your own insanity behind generalities where you say nothing specific but allege insanity on the part of Taney. Please identify at least one Taney claim you consider insane or failing your personal standards.

No law ever automatically manumitted anyone, from Somersett to Scott."

Well, you can quibble over the word "automatically", but the most famous example is Pres. Washington, living in Philadelphia during Pennsylvania's gradual abolition period.

Pennsylvania law required, in effect, that Washington rotate his slaves in Philadelphia after a certain defined time-period, or they would be subject to legally imposed manumission.

Remind me. Did Washington ever manumit his slaves in his lifetime or in his will?

You are never lacking in irrelevant bullflop.

Here are cases more directly related to Dred Scott:"It was expected that the Scotts would win their freedom with relative ease.[21][24]: 241 By 1846, dozens of freedom suits had been won in Missouri by former slaves.[24]

Most had claimed their legal right to freedom on the basis that they, or their mothers, had previously lived in free states or territories.[24]

Among the most important legal precedents were Winny v. Whitesides[25] and Rachel v. Walker.[26]

In Winny v. Whitesides, the Missouri Supreme Court had ruled in 1824 that a person who had been held as a slave in Illinois, where slavery was illegal, and then brought to Missouri, was free by virtue of residence in a free state.[23]: 41

In Rachel v. Walker, the state supreme court had ruled that a U.S. Army officer who took a slave to a military post in a territory where slavery was prohibited and retained her there for several years, had thereby "forfeit[ed] his property".[23]: 42 Rachel, like Dred Scott, had accompanied her enslaver to Fort Snelling.[23]"

Winny v. Whitesides (1824) was overruled by Scott v. Emerson (1852) and was uncitable as precedent.

Rachel v. Walker (1836) had nothing to do with Missouri, and was uncitable as authority to overturn the Supreme Court of Missouri decision in the case of Scott v. Emerson (1852). In Emerson, Rachel v. Walker was cited as case 11 of 14 cases specfically argued to the Court.

As the Court stated in Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo 576 (1852)

In States and Kingdoms in which slavery is the least countenanced, and where there is a constant struggle against its existence, it is admitted law, that if a slave accompanies his master to a country in which [*586] slavery is prohibited, and remains there a length of time, if during his continuance in such country there is no act of manumission decreed by its courts, and he afterwards returns to his master’s domicil, where slavery prevails, he has no right to maintain a suit founded upon a claim of permanent freedom. This is the law of England, where it is said that her air is too pure for a slave to breathe in, and that no sooner does he touch her soil than his shackles fall from him. The case of slave, Grace, 2 Haggard Adm’rl’ty Rep. 94. Story, in his conflict of laws, says, “it has been solemnly decided that the law of England abhors and will not endure the existence of slavery within the nation, and consequently, so soon as a slave lands in England, he becomes ipso facto, a free man, and discharged from the state of servitude; and there is no doubt that the same principle pervades the common law of the non-slaveholding States in America: that is to say, foreign slaves would no longer be deemed such after their removal thither.” But he continues, “it is a very different question how far the original state of slavery might re-attach upon the party, if he should return to the country by whose laws he was declared to be and was held as a slave:” Sec. 95, 6. In the case of the commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Ames, 18, Peck, Judge Shaw, although declining to give an express opinion upon this question, intimates very clearly that if the slave returns to his former country where slavery obtains, his condition would not be changed. In the case of Graham vs. Strader, 5 Mon. 183, the court of Appeals in Kentucky held, that the owner of a slave, who resides in Kentucky, and who permits his slave to go to Ohio in charge of an agent for a temporary purpose, does not forfeit his right of property in such slave. An attempt has been made to show, that the comity extended to the laws of other States, is a matter of discretion, to be determined by the courts of that State in which the laws are proposed to be enforced. If it is a matter of discretion, that discretion must be controlled by circumstances. Times now are not as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequence must be the overthrow and destruction of our government. Under such circumstances it does not behoove the State of Missouri to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit. She is willing to assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery within her limits, nor does she seek to share or divide it with others. Although we may, for our own sakes, regret that the avarice and hard-heartedness of the progenitors of those who are [*587] now so sensitive on the subject, ever introduced the institution among us, yet we will not go to them to learn law, morality or religion on the subject.

Rachel v. Walker was argued to the Court and the losing argument lost.

Do you have any more irrelevant bullflop to spam with, or are you done?

woodpusher: " A slave taken to a free state, while in that free state, might successfully sue for his freedom, but should he return to a slave state, he resumed his status as a slave. This was upheld in English as well as American law. "

Not true, see examples cited above.

As is your habit, due to willful purpose or incompetence, you cite case opinions that were struck down by a higher court, or are just irrelevant. The applicable precedents were set by R. v. Knowles ex rel Somersett, (1772) 20 State Tr 1, (aka Somerset v Steuart); The Slave, Grace, 2 Hagg. 94 (1833); Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82 (1851); and Lemmon v. The People, 20 N.Y. 562 (1860).

The U.S. Supreme Court in Strader v. Graham was especially on point, as was previously cited and quoted to you.

Also consistent is the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82 (1851)

At 93-94:

Every state has an undoubted right to determine the status, or domestic and social condition of the persons domiciled within its territory except insofar as the powers of the states in this respect are restrained, or duties and obligations imposed upon them, by the Constitution of the United States. There is nothing in the Constitution of the United States that can in any degree control the law of Kentucky upon this subject. And the condition of the negroes, therefore, as to freedom or slavery after their return depended altogether upon the laws of that state, and could not be influenced by the laws of Ohio. It was exclusively in the power of Kentucky to determine for itself whether their employment in another state should or should not make them free on their return. The Court of Appeals has determined that by the laws of the state, they continued to be slaves. And their judgment upon this point is, upon this writ of error, conclusive upon this Court, and we have no jurisdiction over it.

woodpusher quoting: "...local [New York] judge ruled that under New York law the "eight colored Virginians," as the judge called them, became free the moment their owner brought them into the state. This decision was consistent with precedents dating from the Somerset case (1772)."

So, it appears that you agree with me on this point, or did you not actually read your own quote?

Unlike you, I both read it and understood it. Since R. v. Knowles, ex re Someset, 1 Lofft (G.B.) 1, (1772) the courts have ruled that if a slave is taken to a jurisdiction that does not recognize the existence of slavery, the slave may petition a court for manumission. Should the same slave return to a slave jurisdiction, as did Dred Scott, the status of slave reattaches and the slave state alone determines the status of the slave. In other words, Dred Scott had no case, had no legal claim to federal jurisdiction, and he quite properly lost in the Missouri Supreme Court and in the United States Supreme Court, despite your collection of spam which you incessantly splat upon the board.

woodpusher quoting on the 1827 British ruling: "Without positive law, the master could not control a slave in England and could not force a slave to leave the realm. But if a slave did return to a slave jurisdiction, as Grace had, then the law of England would no longer be in force and the person's status would once again be determined by the laws of the slave jurisdiction."

So it appears that different courts, in this case a British court, ruled different ways on this matter.

No, moron. When deciding cases presenting DIFFERENT FACTS AND CIRCUMSTANCES, the Court reached different decisions. When the slave litigated while in a free jurisdiction, the slave could not be removed from the jurisdiction by force. However, where the slave returned to a slave jurisdiction, as did The Slave Grace, and as did Etheldred Scott, the law of the free jurisdiction no longer applied and the person's status would be determined by the laws of the slave jurisdiction.

Somerset, Grace, the NY high court in Lemmon v. the People, Scotus in Strader v. Graham, S. Ct. of Missouri in Scott v. Emerson, and Scotus in Scott v. Sandford are all consistent. Litigation presented from a free state good, litigation presented from a slave state no good.

The seven judge majority in Scott was not insane. Your incessant spam is insane.

woodpusher: "Not only was that lawyer from Massachusetts, he was George Curtis, the elder brother of Justice Benjamin Curtis, who saw no reason for recusal."

So, had Justice Curtis recused himself, the vote on Dred Scott would be, instead of 7-2, 7-1 a near unanimous display of Southern control over the 1857 US Supreme Court, thus even more strongly supporting Northern fears that the US Supreme Court was only one decision away from imposing slavery on Northern states.