|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

Posted on 12/13/2002 5:34:26 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

| Our Mission: The FReeper Foxhole is dedicated to Veterans of our Nation's military forces and to others who are affected in their relationships with Veterans. We hope to provide an ongoing source of information about issues and problems that are specific to Veterans and resources that are available to Veterans and their families. In the FReeper Foxhole, Veterans or their family members should feel free to address their specific circumstances or whatever issues concern them in an atmosphere of peace, understanding, brotherhood and support.

|

|

|

|

Summary of the Battle The Little Big Horn battle was easily the worst defeat ever sustained by the U.S. Army in Plains Indian warfare with the 7th Cavalry suffering 268 killed or dying of wounds, and 60 wounded. The news shocked the nation and gave rise to an endless debate about the facts, strategy and tactics of the battle which continues to the present day.  Col. Custer May 17th, 1876 On May 17, 1876, the 7th United States Cavalry Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer left Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, as part of a column commanded by Brigadier General Alfred H. Terry. This column, with two others already in the field led by Brigadier General George Crook and Colonel John Gibbon, was to participate in the effort to force all Sioux and Northern Cheyenne in the unceded territory back to their reservations. When the 7th Cavalry left on the expedition, it did so divided into two wings, the right under Major Marcus A. Reno and the left under Captain Frederick W. Benteen. Within the right wing were the battalions of Captain Myles W. Keogh (Companies B, C and I) and Captain George W. Yates (Companies E, F and L). The left wing was comprised of battalions under Captain Thomas B. Weir (Companies A, D and H) and Captain Thomas H. French (Companies G, K and M). The regiment consisted of approximately 750 officers and enlisted men, although the exact number is open to question, and was accompanied by a contingent of about forty Arikara Indian scouts. Also in the column were three companies of infantry and a Gatling gun platoon, all supported by wagons carrying supplies. June 7th On June 7, Terry's column reached the confluence of the Powder and Yellowstone Rivers from which point he left to confer with Gibbon on June 9, and then returned. The right wing of the 7th Cavalry, along with one Gatling gun, was then ordered on a scout intended to take the unit up the Powder River, then over to the Tongue River, and back to the Yellowstone. Reno exceeded, or disobeyed, those orders by proceeding further west to Rosebud Creek where he found an Indian trail. He followed the trail upstream for perhaps 45 miles before returning to the Yellowstone.  Maj. Reno June 21st On June 21, the remainder of the 7th Cavalry joined Reno below the mouth of the Rosebud and the whole regiment moved to the junction of that stream and the Yellowstone. On the same day, Terry, Gibbon, Custer and Major James Brisbin held a conference on board the steamer Far West. The decision reached was that Gibbon's infantry and Brisbin's 2nd Cavalry would proceed up the Yellowstone, cross and go south up the Big Horn. Custer and the 7th Cavalry were to move south along the Rosebud, then cross to the Little Big Horn, and return along that stream. The obvious hope was that the Indians would be found in the area of the Little Big Horn and be trapped between the two columns. During the course of the meeting, Custer declined the offer of the Gatling gun battery on the grounds that it could hinder his progress. He also refused the four companies of the 2nd Cavalry under Brisbin, saying that the 7th Cavalry could handle anything it met. To assist Custer, six Crow scouts from Gibbon's command were assigned along with the famous civilian guide and scout Mitch Bouyer. George Herendeen was attached to Custer for the purpose of scouting the upper reaches of Tulloch's Fork and carrying the results of that scout to Terry. The conference resulted in the now famous "Orders" dated June 22, to Custer from Terry. The verbal and written battles waged over the meaning, force and effect of these orders began soon after the actual battle ended, and persist even today. June 22nd At noon on June 22, the 7th Cavalry proceeded up the Rosebud about 12 miles. While at the Yellowstone, Custer had abolished the wing/battalion assignments for reasons unknown, informing Reno that command assignments would be made on the march. That evening, Custer told his assembled officers that he expected they might face a warrior force of up to 1500, and if he got on their trail he would pursue, even if beyond the fifteen days for which they were rationed. The regimental supplies were carried by a make-shift mule train of twelve mules per company with some additional animals to transport headquarters and miscellaneous equipment. Twelve mules each carried two 1000-round ammunition boxes, or 2000 rounds per company. Each soldier was armed with the single-shot, .45 caliber, Model 1873 Springfield carbine, and was ordered to carry 100 rounds of 45-55 carbine ammunition of which fifty rounds was to be on his person. The troopers also carried the Model 1873 Colt .45 caliber, single-action revolver with twenty four rounds of ammunition. Despite artwork to the contrary, no sabres were carried after the expedition left the Powder River camp. It further appears from recent archeological surveys that some of the soldiers may have carried weapons other than those mentioned, and that some men and officers had "personal" weapons with them.  Capt. Benteen June 24th Saturday, June 24, found the regiment on the march by 5 a.m. Indian campsites were passed and examined and, after a march of some 28 miles, the command went into camp. That evening Custer called First Lieutenant Charles A. Varnum to him and stated that the Crow scouts believed the Sioux were in the Little Big Horn valley. Custer wanted someone to accompany the Crows scouts to a spot, later to become famous as the "Crow's Nest," from which the scouts said they could see the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne camp fires when started in the early morning. Custer wanted a messenger to be sent back with information as soon as possible. Varnum was to leave about 9 p.m. and Custer would follow with the regiment at 11 p.m. and thought he could be at the base of the divide between the Rosebud and Little Big Horn before morning. Varnum along with Charlie Reynolds, a white scout, some Crow and Arikara scouts left as ordered. Custer turned the regiment westward toward the divide and marched about four hours until the weary unit halted. At this point, a message was received from Varnum stating that the scouts had seen camp fire smoke and a pony herd in the valley, and the regiment again moved out about 8 a.m. Later that morning Custer arrived at the Crow's Nest, looked through field glasses at the indicated site but, like Varnum earlier, was unable to see what the Crow scouts had seen. Although Benteen later claimed Custer did not believe the scouts' report, Custer's subsequent actions were those of a commander taking his command toward a scene of action. Upon his return to the regiment, Custer was told that a detail of troopers, led by Sergeant William A. Curtis of F Company, had come upon an Indian trying to open a lost box or bundle of clothing. There were other reports from Herendeen and Bouyer of sightings of Indians who, it was assumed, had also discovered the regiment. Since it was the Indians' custom to scatter in the presence of troops, Custer decided to strike immediately, rather than lay concealed during June 25 and attack on the morning of the 26th. June 25th  At about noon on June 25, at the Rosebud-Little Big Horn divide, Custer halted the regiment and proceeded to assign commands. Reno received Companies A, G and M, and Benteen, Companies D, H and K. It is probable that Captain Keogh was given Companies I, L and C, and Captain Yates, Companies E and F. Captain Thomas McDougall's Company B was assigned as packtrain guard. Furthermore, a noncommissioned officer and six privates were detailed from each company to help with company pack mules. Benteen was ordered to scout toward a line of hills to the left front. After his departure, two messengers were sent directing him to go beyond the line of hills in view. This scout is sometimes characterized as Custer's way of appearing to comply with Terry's directive that he feel "... constantly to your left ..," but more likely represents Custer's reaction to his experience at the Washita, when he found that Indian villages camped separately along the same stream. The balance of the regiment proceeded down Reno (or Sundance, or Ash) Creek toward the Little Big Horn, Reno's command on the left bank and Custer's two battalions on the right, with the pack train bringing up the rear. Around 2 p.m. Reno's battalion crossed over the creek to join Custer's command on the right bank. Shortly after, the combined columns arrived in the vicinity of the Lone Tepee, the location of which is still a matter of dispute. Near this point, Fred Girard, civilian interpreter for the Arikara scouts, spotted a group of Indians fleeing toward the river, and heavy dust clouds were seen in the valley. Riding to the top of a small knoll, Girard called out to Custer, "Here are your Indians, running like devils." Custer sent his adjutant, First Lieutenant William W. Cooke, to Reno with the order, "Custer says to move at as rapid a gait as you think prudent and to charge afterwards, and you will be supported by the whole outfit." This was the last and only order Reno ever received and, in fact, was the last communication from Custer's command. In obedience to the order, Reno proceeded to the Little Big Horn River at a fast trot, crossed and halted on the far side of some timber to gather the companies which had lost formation in the crossing. Meanwhile, Girard still on the right bank had heard the Crow and Arikara call out that the Sioux, in large numbers, were coming up to meet Reno, an observation also made by the scout Herendeen. Thinking that Custer should know of this development, he turned back and quickly came upon Cooke who was riding toward the river. After Girard relayed his information, Cooke stated he would report to Custer and turned back immediately. Reno advanced down the valley toward the Indian village which was about two miles from the river crossing. During this movement Reno sent two separate messages, carried by Privates Archibald McIlhargey and John Mitchell, to Custer, each with the same information that the Indians were in force in front of him.  Sitting Bull Indians poured across Reno's front, many moving to the bluffs on his left. Reno halted and dismounted his command of 128 soldiers to fight in a skirmish line formation, with his right resting on the timber near the river, and extending to his left toward the bluffs. The line advanced about 100 yards toward the village, but no further. Reno sent the horses and G Company into the timber. Out on the valley floor the battle continued, and as the Indians moved to Reno's left, he withdrew the skirmish line to the edge of the timber. The length of the fight until the line withdrew is a matter of argument with opinions ranging from five minutes to a half-hour. Once in the timber, the fight continued until Reno, not receiving the promised support of "the whole outfit," and concerned about the expenditure of non-replaceable ammunition, decided to withdraw to the bluffs on the east side of the river. Varnum, Lieutenant Charles C. DeRudio, and the scout Herendeen, all saw Custer and/or his command moving north along the bluffs to the east of the Little Big Horn, but no one informed Reno of Custer's movements! Reno was able to mount most, but clearly not all, of his command in a clearing in the timber. A volley of shots rang out and the Arikara scout, Bloody Knife, at Reno's side, died from a bullet in the head, spattering blood and brains over Reno. Orders to dismount, then mount were given, and the command left the timber for the eastern heights. No organized resistance to the onslaught of the warriors took place either during the retreat or at the river crossing. This retreat, called a charge by Reno, resulted in the reported loss of three officers, at least twenty nine enlisted men, three civilians and two Arikara scouts. It terminated on the bluffs near the current Reno-Benteen battle site, and the result at the time must have appeared even worse, for in addition to those ultimately found dead, there were an officer, three civilians and fifteen soldiers missing, all but four of whom rejoined later that afternoon. Shortly after reaching the bluffs, Reno was joined by Benteen's battalion which had returned to the trail some distance above the Lone Tepee. On his way to the river, Benteen was passed by Sergeant Daniel Kanipe of Company C who carried a message to the pack train. The message was for the train to come on across country and, in essence, not to worry about the loss of packs unless they contained ammunition. Benteen was next met by Trumpeter John Martin of Benteen's own Company H with the now famous, and disputed, message, "Benteen, Come on. Big village, Be quick. Bring packs. W.W. Cooke. P. S. Bring Packs." The dispute over this latter message is whether or not its intent was to have Benteen bring forward only the twelve mules with all the reserve ammunition. Proponents of the "ammunition packs" theory assert that Custer intended to make a stand and would need the reserve ammunition. Opponents point out that the word "ammunition" is not used, that Custer had not yet even become engaged, and that to sequester all the ammunition implies an indifference to the fate of Reno and the pack train. In any event, Benteen reached the river in time to see the last of Reno's "charge" to the bluffs. He joined the shattered unit and Lieutenant Luther Hare was swiftly dispatched to the pack train to bring up several mules with ammunition. At about the same time, firing down river was heard indicating that Custer was engaged. In response to this, Weir, on his own, started down river perhaps thirty- five minutes after arrival at Reno's position. Lieutenant Winfield S. Edgerly, believing Weir had permission to advance, ordered Company D to mount and follow. This precipitated the disjointed movement by Reno's command. Upon arrival of McDougall and the pack train, Companies H, K and M followed D to a prominent point along the bluffs (today known as Weir Point) and the remainder of the command started in that direction but made little progress. The units on Weir Point abandoned that position and, again in a rather uncontrolled manner, moved back to the area occupied during the siege. The movement was prevented from becoming a disaster by Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey, who on his own authority, dismounted K Company and covered the retreat. Reno's command was quickly surrounded and came under heavy fire. Earlier that afternoon, when Custer gave his last order to Reno, he probably had no plan for an enveloping maneuver. However, as he approached the river he was met by Adjutant Cooke bringing Girard's information that the Indians were coming up to meet Reno. This was almost immediately reinforced by the arrival of the first of the soldiers sent by Reno with a message to the same effect. The arrival of the second soldier added emphasis to the fact that a large number of Indians were in the valley. The dust in the valley probably indicated to Custer that the noncombatants were fleeing north. A flanking maneuver to get to the women and children and, at the same time, placing the warriors between him and Reno must have seemed appropriate. In any event, Custer turned north.  Crazy Horse Then What? From this point on, there are few absolutes about Custer's action except its outcome. Theories abound. The last soldiers to see him were Kanipe, sent back when Custer first reached a bluff overlooking the river, and Trumpeter Martin, whose point of departure is disputed. Some writers place it in Cedar Coulee and others at the junction of Custer's northward approach and Medicine Tail Coulee, for Martin himself said they had reached a ravine which ran toward the river. There is controversy whether Custer moved along the bluffs next to the river or behind Sharpshooter's Ridge, a prominence north of the Reno-Benteen defense site. Likewise, there are differences of opinion about whether or not Custer personally went to Weir Point, the highest point nearest the river. This would have afforded Custer an unlimited view of the village had he gone there. In opposition, there is the unquestioned fact that at least four Crow scouts were definitely on Weir Point and not one of them places Custer, or any other soldier, there at any time. Additionally, Martin testified that only the Crow scouts went to Weir Point and that Custer was never there. No matter the route, from there we know, with reasonable certainty, the location of the dead, though the theories of Custer's final actions are numerous. Passing Sharpshooter's Ridge and proceeding down Cedar Coulee, Custer and his men arrived and halted at the junction of Cedar and South Medicine Tail Coulees. One part of Custer's command, probably Keogh's battalion, with three companies, moved north and occupied areason what is known as Nye-Cartwright Ridge. This ridge divides South Medicine Tail Coulee and North Medicine Tail Coulee, sometimes called Deep Coulee. The latter is the deep ravine at the base of the ridge which runs from Calhoun Hill toward the Little Big Horn where it joins the mouth of South Medicine Tail. Cartridge casing finds clearly indicate troops firing from that point, and any concept of Custer's final battle must include that action if it is to have any validity.

|

You're welcome J

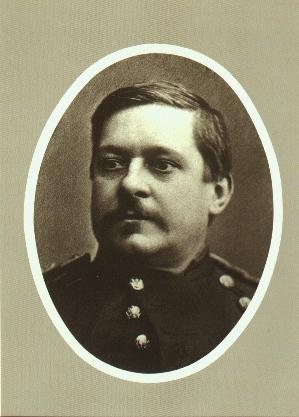

"Portrait of Chief Crazy Horse"

Herein is an enlargement of what I believe is an authentic picture of Crazy Horse. The original is a small tintype, 2 1/2 X 3 1/2 inches, in excellant condition. Its first owner was Baptiste Garnier (Little Bat) the famous scout and frontiersman. When Bat was murdered in 1900 it went to his wife; on her death it was inherited by her daughter, Ellen Howard, from whom Mr. Hackett obtained it, after which it came to me, so the line of ownership is quite clear. I have a certificate from Mrs. Howard attesting that the tintype belonged to her father, and that it had been in the family since it had been made. She also says that her father told his family that it was truly a picture of Crazy Horse.

First publication was by J. W. Vaughn in his excellant With Crook at the Rosebud, (Stackpole, 1956). The account tells of finding the picture in an old trunk, which is probably true, but after that point my investigations do not agree with the information supplid to Mr. Vaughn. The account said the picture was taken about 1870 at Fort Laramie. There were two other pictures, one of Little Bat and his wife, and the other of Bat and Frank Grouard. We do not know if they were part of the same series but if they were, they were not taken in 1870 for the following reasons: Grouard tells in his biography, Life and Adventures of Frank Grouard, by Joe DeBarthe (1894, p. 117), that he met Crazy Horse for the first time just a few days after the battle between the Sioux and the Stanley Expedition on the Yellowstone River - this took place August 4th, 1873. Another point, in 1870 Bat was 15 or 16 years old; I do not believe a war chief of the Oglalas was hanging around with a teen-ager. Crazy Horse had been made a chief only a little more than a year previous - he was out in the hinterlands with his band of warriors and their families; he was not hanging around the fort for the white man's handouts as did Red Cloud and Spotted Tail. At this time and for several more years probably his only contact with the white man was across the sights of his Winchester.

Following their surrender in May 1877, Crazy Horse and his chief warriors were signed up as Indian Scouts ostensibly to keep tab on the Nez Perce, but with Lieutenant Clark on the job you may be sure they were under his eagle eye both day and night. The whites were afraid of this man and kept close track of his every move, so he was not let out on any scouting trips. Time was very heavy on his hands, the tiny details of every day living were a nuisance to him, begging for supplies and food, or settling a quarrel between the women, so one day when Little Bat rode past the camp on his way to Fort Robinson he easily persuaded Crazy Horse to come along and see what they could see. Crazy Horse liked Bat, and Mrs. Bat was a cousin of his, so he was at ease and relaxed, being with his friends. While at the Fort, with everyone in high good humor Bat dared Crazy Horse to have his picture taken, and he finally consented. According to the story he even borrowed the moccasins to make a good appearance. I know all previous picture requests had been refused; these had all been made by white men, and the white man had been trying for years to kill Crazy Horse and his people, so why should he do even the slightest favor for them. Also, on this last summer of his life he did a number of things he had never done before. On this one time he let down his guard for his good friend Bat. We also know there was a photographer at the Fort in the summer of 1877 as I have another photo stamped Fort Robinson in the mounting and this was taken in 1877.

The picture shows an Indian of medium stature, lighter-haired than the average Indian, with a rounded face rather than one with high, wide cheekbones. His hair is in two braids to his waist, and he wears two feathers which was customary for Crazy Horse. Mr. Hackett has a set of feathers given him by an old chief and they are exactly similar to those shown in the photo. Also the picture shows clearly the scar in the left corner of his mouth where he was shot some years before by No Water, after he had ridden away with No Water's wife.

It is unfortunate that the secretive nature of the old-time Indians dealing with whites caused this picture to be so long hidden. We know of trunks and bags which still hold relics of the Custer battle. Even thrity years ago would have been sufficient for proper identification, as He Dog lived until 1936, and Docotor McGillycuddy who knew and liked Crazy Horse, lived until June of 1939. Either man could have said yes or no at first glimpse, but neither saw it and now it is too late. From the people involved and my searches I firmly believe this is an authentic likeness of Crazy Horse...written by Carroll Friswold

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.