Posted on 11/24/2002 7:30:41 AM PST by SAMWolf

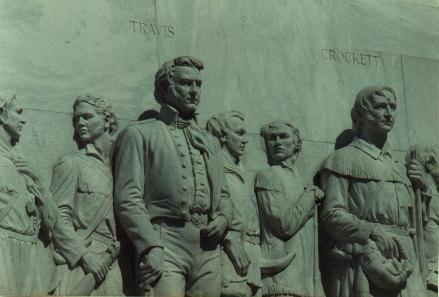

The siege and the final assault on the Alamo in 1836 constitute the most celebrated military engagement in Texas history. The battle was conspicuous for the large number of illustrious personalities among its combatants. These included Tennessee congressman David Crockett, entrepreneur-adventurer James Bowie, and Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna. Although not nationally famous at the time, William Barret Travis achieved lasting distinction as commander at the Alamo. For many Americans and most Texans, the battle has become a symbol of patriotic sacrifice. Traditional popular depictions, including novels, stage plays, and motion pictures, emphasize legendary aspects that often obscure the historical event.

To understand the real battle, one must appreciate its strategic context in the Texas Revolution. In December 1835 a Federalist army of Texan (or Texian, as they were called) immigrants, American volunteers, and their Tejano allies had captured the town from a Centralist force during the siege of Bexar. With that victory, a majority of the Texan volunteers of the "Army of the People" left service and returned to their families. Nevertheless, many officials of the provisional government feared the Centralists would mount a spring offensive. Two main roads led into Texas from the Mexican interior. The first was the Atascosito Road, which stretched from Matamoros on the Rio Grande northward through San Patricio, Goliad, Victoria, and finally into the heart of Austin's colony. The second was the Old San Antonio Road, a camino real that crossed the Rio Grande at Paso de Francia (the San Antonio Crossing) and wound northeastward through San Antonio de Béxar, Bastrop, Nacogdoches, San Augustine, and across the Sabine River into Louisiana. Two forts blocked these approaches into Texas: Presidio La Bahía (Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio) at Goliad and the Alamo at San Antonio. Each installation functioned as a frontier picket guard, ready to alert the Texas settlements of an enemy advance. James Clinton Neill received command of the Bexar garrison. Some ninety miles to the southeast, James Walker Fannin, Jr., subsequently took command at Goliad. Most Texan settlers had returned to the comforts of home and hearth. Consequently, newly arrived American volunteers-some of whom counted their time in Texas by the week-constituted a majority of the troops at Goliad and Bexar. Both Neill and Fannin determined to stall the Centralists on the frontier. Still, they labored under no delusions. Without speedy reinforcements, neither the Alamo nor Presidio La Bahía could long withstand a siege.

At Bexar were some twenty-one artillery pieces of various caliber. Because of his artillery experience and his regular army commission, Neill was a logical choice to command. Throughout January he did his best to fortify the mission fort on the outskirts of town. Maj. Green B. Jameson, chief engineer at the Alamo, installed most of the cannons on the walls. Jameson boasted to Gen. Sam Houston that if the Centralists stormed the Alamo, the defenders could "whip 10 to 1 with our artillery." Such predictions proved excessively optimistic. Far from the bulk of Texas settlements, the Bexar garrison suffered from a lack of even basic provender. On January 14 Neill wrote Houston that his people were in a "torpid, defenseless condition." That day he dispatched a grim message to the provisional government: "Unless we are reinforced and victualled, we must become an easy prey to the enemy, in case of an attack."

By January 17, Houston had begun to question the wisdom of maintaining Neill' s garrison at Bexar. On that date he informed Governor Henry Smith that Col. James Bowie and a company of volunteers had left for San Antonio. Many have cited this letter as proof that Houston ordered the Alamo abandoned. Yet, Houston's words reveal the truth of the matter:

"I have ordered the fortifications in the town of Bexar to be demolished, and, if you should think well of it, I will remove all the cannon and other munitions of war to Gonzales and Copano, blow up the Alamo and abandon the place, as it will be impossible to keep up the Station with volunteers, the sooner I can be authorized the better it will be for the country."

Houston may have wanted to raze the Alamo, but he was clearly requesting Smith's consent. Ultimately, Smith did not "think well of it" and refused to authorize Houston' s proposal.

On January 19, Bowie rode into the Alamo compound, and what he saw impressed him. As a result of much hard work, the mission had begun to look like a fort. Neill, who well knew the consequences of leaving the camino real unguarded, convinced Bowie that the Alamo was the only post between the enemy and Anglo settlements. Neill's arguments and his leadership electrified Bowie. "I cannot eulogize the conduct & character of Col. Neill too highly," he wrote Smith; "no other man in the army could have kept men at this post, under the neglect they have experienced." On February 2 Bowie wrote Smith that he and Neill had resolved to "die in these ditches" before they would surrender the post. The letter confirmed Smith's understanding of controlling factors. He had concluded that Bexar must not go undefended. Rejecting Houston's advice, Smith prepared to funnel additional troops and provisions to San Antonio. In brief, Houston had asked for permission to abandon the post. Smith considered his request. The answer was no.

Colonel Neill had complained that "for want of horses," he could not even "send out a small spy company." If the Alamo were to function as an early-warning station, Neill had to have outriders. Now fully committed to bolstering the Bexar garrison, Smith directed Lt. Col. William B. Travis to take his "Legion of Cavalry" and report to Neill. Only thirty horsemen responded to the summons. Travis pleaded with Governor Smith to reconsider: "I am unwilling to risk my reputation (which is ever dear to a soldier) by going off into the enemy' s country with such little means, and with them so badly equipped." Travis threatened to resign his commission, but Smith ignored these histrionics. At length, Travis obeyed orders and dutifully made his way toward Bexar with his thirty troopers. Reinforcements began to trickle into Bexar. On February 3, Travis and his cavalry contingent reached the Alamo. The twenty-six-year-old cavalry officer had traveled to his new duty station under duress. Yet, like Bowie, he soon became committed to Neill and the fort, which he began to describe as the "key to Texas." About February 8, David Crockett arrived with a group of American volunteers.

On February 14 Neill departed on furlough. He learned that illness had struck his family and that they desperately needed him back in Bastrop. While on leave, Neill labored to raise funds for his Bexar garrison. He promised that he would resume command when circumstances permitted, certainly within twenty days, and left Travis in charge as acting post commander. Neill had not intended to slight the older and more experienced Bowie, but Travis, like Neill, held a regular army commission. For all of his notoriety, Bowie was still just a volunteer colonel. The Alamo's volunteers, accustomed to electing their officers, resented having this regular officer foisted upon them. Neill had been in command since January; his maturity, judgment, and proven ability had won the respect of both regulars and volunteers. Travis, however, was unknown. The volunteers insisted on an election, and their acting commander complied with their wishes. The garrison cast its votes along party lines: the regulars voted for Travis, the volunteers for Bowie. In a letter to Smith, Travis claimed that the election and Bowie's subsequent conduct had placed him in an "awkward situation." The night following the balloting, Bowie dismayed Bexar residents with his besotted carousal. He tore through the town, confiscating private property and releasing convicted felons from jail. Appalled by this disorderly exhibition, Travis assured the governor that he refused to assume responsibility "for the drunken irregularities of any man"-not even the redoubtable Jim Bowie. Fortunately, this affront to Travis's sense of propriety did not produce a lasting breach between the two commanders. They struck a compromise: Bowie would command the volunteers, Travis the regulars. Both would co-sign all orders and correspondence until Neill's return. There was no more time for personality differences. They had learned that Santa Anna's Centralist army had reached the Rio Grande. Though Travis did not believe that Santa Anna could reach Bexar until March 15, his arrival on February 23 convinced him otherwise. As Texans gathered in the Alamo, Travis dispatched a hastily scribbled missive to Gonzales: "The enemy in large force is in sight. We want men and provisions. Send them to us. We have 150 men and are determined to defend the garrison to the last." Travis and Bowie understood that the Alamo could not hold without additional forces. Their fate now rested with the General Council in San Felipe, Fannin at Goliad, and other Texan volunteers who might rush to assist the beleaguered Bexar garrison.

Santa Anna sent a courier to demand that the Alamo surrender. Travis replied with a cannonball. There could be no mistaking such a concise response. Centralist artillerymen set about knocking down the walls. Once the heavy pounding reduced the walls, the garrison would have to surrender in the face of overwhelming odds. Bottled up inside the fort, the Texans had only one hope-that reinforcements would break the siege.

On February 24 Travis assumed full command when Bowie fell victim to a mysterious malady variously described as "hasty consumption" or "typhoid pneumonia." As commander, Travis wrote his letter addressed to the "people of Texas & all Americans in the world," in which he recounted that the fort had "sustained a continual Bombardment and cannonade for 24 hours." He pledged that he would "never surrender or retreat" and swore "Victory or Death." The predominant message, however, was an entreaty for help: "I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch." On March 1, thirty-two troops attached to Lt. George C. Kimbell's Gonzales ranging company made their way through the enemy cordon and into the Alamo. Travis was grateful for any reinforcements, but knew he needed more. On March 3 he reported to the convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos that he had lost faith in Colonel Fannin. "I look to the colonies alone for aid; unless it arrives soon, I shall have to fight the enemy on his own terms." He grew increasingly bitter that his fellow Texans seemed deaf to his appeals. In a letter to a friend, Travis revealed his frustration: "If my countrymen do not rally to my relief, I am determined to perish in the defense of this place, and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect."

On March 5, day twelve of the siege, Santa Anna announced an assault for the following day. This sudden declaration stunned his officers. The enemy's walls were crumbling. No Texan relief column had appeared. When the provisions ran out, surrender would remain the rebels' only option. There was simply no valid military justification for the costly attack on a stronghold bristling with cannons. But ignoring these reasonable objections, Santa Anna stubbornly insisted on storming the Alamo. Around 5:00 A.M. on Sunday, March 6, he hurled his columns at the battered walls from four directions. Texan gunners stood by their artillery. As about 1,800 assault troops advanced into range, canister ripped through their ranks. Staggered by the concentrated cannon and rifle fire, the Mexican soldiers halted, reformed, and drove forward. Soon they were past the defensive perimeter. Travis, among the first to die, fell on the north bastion. Abandoning the walls, defenders withdrew to the dim rooms of the Long Barracks. There some of the bloodiest hand-to-hand fighting occurred. Bowie, too ravaged by illness to rise from his bed, found no pity. The chapel fell last. By dawn the Centralists had carried the works. The assault had lasted no more than ninety minutes. As many as seven defenders survived the battle, but Santa Anna ordered their summary execution. Many historians count Crockett as a member of that hapless contingent, an assertion that still provokes debate in some circles. By eight o'clock every Alamo fighting man lay dead. Currently, 189 defenders appear on the official list, but ongoing research may increase the final tally to as many as 257.

Though Santa Anna had his victory, the common soldiers paid the price as his officers had anticipated. Accounts vary, but best estimates place the number of Mexicans killed and wounded at about 600. Mexican officers led several noncombatant women, children, and slaves from the smoldering compound. Santa Anna treated enemy women and children with admirable gallantry. He pledged safe passage through his lines and provided each with a blanket and two dollars. The most famous of these survivors were Susanna W. Dickinson, widow of Capt. Almaron Dickinson, and their infant daughter, Angelina Dickinson. After the battle, Mrs. Dickinson traveled to Gonzales. There, she reported the fall of the post to General Houston. The sad intelligence precipitated a wild exodus of Texan settlers called the Runaway Scrape.

What of real military value did the defenders' heroic stand accomplish? Some movies and other works of fiction pretend that Houston used the time to raise an army. During most of the siege, however, he was at the Convention of 1836 at Washington-on-the-Brazos and not with the army. The delay did, on the other hand, allow promulgation of independence, formation of a revolutionary government, and the drafting of a constitution. If Santa Anna had struck the Texan settlements immediately, he might have disrupted the proceedings and driven all insurgents across the Sabine River. The men of the Alamo were valiant soldiers, but no evidence supports the notion-advanced in the more perfervid versions-that they "joined together in an immortal pact to give their lives that the spark of freedom might blaze into a roaring flame." Governor Smith and the General Council ordered Neill, Bowie, and Travis to hold the fort until support arrived. Despite all the "victory or death" hyperbole, they were not suicidal. Throughout the thirteen-day siege, Travis never stopped calling on the government for the promised support. The defenders of the Alamo willingly placed themselves in harm's way to protect their country. Death was a risk they accepted, but it was never their aim. Torn by internal discord, the provisional government could not deliver on its promise to provide relief, and Travis and his command paid the cost of that dereliction. As Travis predicted, his bones did reproach the factious politicos and the parade ground patriots for their neglect. Even stripped of chauvinistic exaggeration, however, the battle of the Alamo remains an inspiring moment in Texas history. The sacrifice of Travis and his command animated the rest of Texas and kindled a righteous wrath that swept the Mexicans off the field at San Jacinto. Since 1836, Americans on battlefields over the globe have responded to the exhortation, "Remember the Alamo!"

Besieged by Santa Anna, who had reached Bexar on February 23, 1836, Colonel William Barret Travis, with his force of 182, refused to surrender but elected to fight and die, which was almost certain, for what they thought was right. The position of these men was known but no aid reached them. The request to Colonel James W. Fannin for assistance had gone unheeded. No relief was in store. As the Battle of the Alamo was in progress, a part of the Texas Army had assembled in Gonzales under the command of Mosely Baker in the latter part of February. From this army, a gallant band of 32 courageous men under the command of George C. Kimble left to join the garrison at the Alamo. Making their way through the enemy lines, these 32 men joined the doomed defenders and perished with them.

On March 2, 1836, during the siege of the Alamo, Texas independence was declared. Four days later, the document was signed with the blood shed at the Alamo. It was under such conditions that Travis and his men fought off the much larger force under Santa Anna. It was with the love of liberty in his voice and the courage of the faithful and brave that Travis gave his men the none too cheerful choice of the manner in which they wished to die.

Realizing that no help could be expected from the outside and that Santa Anna would soon take the Alamo, Travis addressed his men, told them that they were fated to die for the cause of liberty and the freedom of Texas. Their only choice was in which way they would make the sacrifice. He outlined three procedures to them: first, rush the enemy, killing a few but being slaughtered themselves in the hand-to-hand fight by the overpowering Mexican force; second, to surrender, which would eventually result in their massacre by the Mexicans, or, third, to remain in the Alamo and defend it until the last man, thus giving the Texas army more time to form and likewise taking a greater toll among the Mexicans.

The third choice was the one taken by the men. Their fate was death and they faced it bravely, asking no quarter and giving none. The siege of the Alamo ended on the dawn of March 6, when its gallant defenders were put to the sword. But it was not an idle sacrifice that men like Travis and Davy Crockett and James Bowie made at the Alamo. It was a sacrifice on the altar of liberty.

They already did the re-write on the Alamo. The discovery channel was making the claim that Davey Crockett had not died fighting, but had been captured and executed by Santa Ana. It appeared to me that the entire History's Mysteries (that's what they called it) was designed to cast doubt on Davey Crockett and the battle.

Discovery Channel also had their "experts" who couldn't prove anything, but also they weren't disproved.

The final parting shots of the liberal pc ninnies, was to say that history should be re-written to show that the men at the Alamo weren't so brave, weren't so large, and that those good ol' white boys have hogged history for too long. /disgust

The forensics of the battle would have been very interesting if they could have kept it to history, to what they could prove, but they didn't. They took every opportunity to insert agendas into what should have been a scientific search. It's a pity. I know they wanted people to come away thinking bad thoughts about the men at the Alamo, but instead, they just made me all the angrier.

A hundred and eighty were challenged by Travis to die

A line that he drew with his sword when the battle was nigh

The man who would fight to the death cross over

But him that would live better fly

And over the line stepped a hundred and seventy nine

High up, Santa Ana, we're killin' your soldiers below

So the rest of Texas will know

And remember the Alamo

Jim Bowie lay dyin', his powder was ready and dry

From flat on his back Bowie killed him a few in reply

And young Davy Crockett was smilin' and laughin'

The challenge was fierce in his eye

For Texas and freedom, a man more than willing to die

High up, Santa Ana, we're killin' your soldiers below

So the rest of Texas will know

And remember the Alamo

A courier sent through the battlements, bloody and loud

With words of farewell, and the letters he carried were proud

"Grieve not, little darlin', my dyin'

If Texas is sovereign and free

We'll never surrender and ever will liberty be"

High up, Santa Ana, we're killin' your soldiers below

So the rest of Texas will know

And remember the Alamo

Agreed. Unfortunately, they are finding that there are those of here in Texas are not so ready to let them destroy our past. We're not trying to re-write it, mind you, but we won't let them alter it now.

We need more people to remember our past, not to forget it, not to try to wipe away the blood and the pain.

Those PC twerps are trying so hard to make sure that the minds they are molding believe that no good was ever done by the white man, and that all faults with the world can be laid at our feet.

While I was watching that "special" in my mind I could see the next follow-up. It would read "gang of angry white thieves routed by honorable mexican gentleman."

I'm not saying that there weren't honorable men on both sides of that battle, but to allow history to be changed on the basis of a forged (they found 5 distinct people wrote it) diary that somehow managed to survive all of these years to suddenly appear with no provenence, and an owner unwilling to give any... well, that's suspicious if you ask me.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.