Skip to comments.

Why Statists Always Get it Wrong

The von Mises Institute ^

| Monday, February 20, 2006

| Per Bylund

Posted on 02/20/2006 6:24:40 AM PST by Shalom Israel

Why Statists Always Get it Wrong

by Per Bylund

[Posted on Monday, February 20, 2006]

[Subscribe at email services and tell others]

In a recent article, Carl Milsted uses Rothbard to argue it would be permissible to use force to make people pay for a service of which their benefit is at least double its cost. His conclusion is that it is reasonable, and even preferable, to establish a minimalist state if it is to people's advantage.

In a recent article, Carl Milsted uses Rothbard to argue it would be permissible to use force to make people pay for a service of which their benefit is at least double its cost. His conclusion is that it is reasonable, and even preferable, to establish a minimalist state if it is to people's advantage.

As has already been argued by N. Stephan Kinsella, he totally misses Rothbard's point. Furthermore, he fails to show why people would not choose to voluntarily pay for services which would benefit them double, as has been pointed out by Bob Kaercher.

Even so, I wish to offer another analysis of Milsted's reasoning. His article is a good example of why statists always seem to get it wrong — and why they always fail to understand what we're talking about. The bottom line is that they fail to realize the costs of force due to their unwillingness to see the state for what it is. I will therefore use Milsted's own example to shed light on his fundamental mistake.

Milsted takes the case of national defense, which is commonly considered an institution that would face the free rider problem if supplied on the market. Argues Milsted: "suppose the majority assesses a tax on everyone to spread the burden of supporting the new defense system. This is theft of the minority. However, suppose that the economies of scale are such that this tax is less than half of what people would have had to pay for defense on their own."

That's the argument, plain and simple. If it is morally permissible to steal when the victim is compensated double, the equation seems to fit. Well, let's look into this in more detail and see if it really does.

First, consider a situation where everybody benefits, say, $10,000 on a yearly basis from being protected by a national defense. That would mean, if the premise is correct, that it would be morally permissible to force costs of no more than $5,000 on everybody.

Were it a company supplying a service worth $10,000 to each of its customers paying only $5,000 for it, this would be easy. Anyone willing to pay the $5,000 would get the service, and the costs associated with administration and so forth would have to be covered by the $5,000 paid. But Milsted argues the $5,000 should be taxed, and that makes it much more difficult.

First of all, we know state-run businesses and authorities (especially if they are monopolies) tend to be much less efficient than private enterprises. That means people in Milstedistan would get less than they would in a free market society. But even so, there is still the cost of coercion totally neglected by Milsted in his article.

Forcing people to pay for a service means there will always be someone who tries to avoid paying or even refuses to pay. So "we" (i.e., the state) need to invest in collection services to get the money. Now, let's say Murray, who is one of the people we're trying to coerce, goes out to buy a rifle and then declares that he's "anti-government, so get the hell off my property." Perhaps he even threatens to kill the collection agents. Dealing with him would take a whole lot more out of the budget, meaning there is even less to provide for the defense (which is the reason we're in business in the first place).

But that's not all. Let's say Murray won't give us the money no matter how much we ask or threaten him. We will simply have to take it by force, so we need to invest in the necessary tools and we go out to hire a dozen brutes to do the forcing. (More money down the drain … ) It is already pretty obvious we're in a very expensive business; there will not be much defense left if there are a lot of Murrays in our society.

Now imagine our hired brutes go down the street to Murray's house and knock on his door. He sticks his rifle out the window and shouts something about having the right to his property and that he will shoot to kill. Anyway, the brutes try to open his door only to find it is locked and barred. They will have to break in to finally get their hands on Murray's cash.

Our small army goes back to their van to get their tools, then returns to break down Murray's door. Going inside, they manage to avoid all the bullets Murray is firing and they tie him up and put him in the closet. They eventually find that he does not have any valuables and that he keeps his cash in a locked safe. So they have to break it to get the money.

Now we have a problem. To make this operation morally permissible, the benefit to Murray, which we know is $10,000, must be at least double the cost forced on him. The cost is now a whole lot more than the cost of the national defense; it includes administration and collection costs, hiring the brutes and their tools, as well as the broken door and safe, and the time and suffering (and perhaps medical expenses) Murray has lost while we were stealing from him. How much do you think is left from the original $5,000 to invest in a national defense? Not much.

What if Murray suffers from paranoia and therefore had invested $1,500 in an advanced special security door and $2,000 in an extra security safe? Then the total cost of simply getting into Murray's safe would probably exceed the $5,000 we are "allowed" to steal. What then? Should we break in anyway since it is a mandatory tax, only to give him a check to cover what's above the $5,000 mark? That doesn't sound right.

But on the other hand, if we just let him be, more people would do the same as Murray only to get off, and we would have a huge problem on our hands. This is a typical state dilemma: it costs too much to force money from some people, but it would probably be much more "expensive" in the long run not to. It's a lose-lose situation.

Now, what if Murray is very poor and doesn't have the $5,000? Then we would have to take whatever he's got and make him work off the rest. We need to get the $5,000 to cover our expenses of the national defense, and we have the right to take that amount from him. It could, of course, be argued he couldn't possibly benefit $10,000 from a national defense if he has no money and no property. If we trust Austrian economics, that might very well be correct; the benefit of national defense would, like any other product or service, be valued subjectively and thus the benefit would be different for each and every individual.

If this is true, it means we have an even greater problem: the state can rightfully levy costs of a maximum of half the subjective benefit enjoyed. Well, that's a task that would keep an army of Nobel Prize winners busy for a while. If possible, I wonder how much that would cost in the end.

This is the problem statists face on an everyday basis when discussing philosophy and politics. It is easy to make nice equations and formulas, and theorize on great systems and cheap solutions neatly enforced by the state. But when consistently failing to realize the costs of coercion it makes their reasoning fundamentally flawed. Just scratching the surface reveals they really have no clue whatsoever.

Per Bylund works as a business consultant in Sweden, in preparation for PhD studies. He is the founder of Anarchism.net. Send him mail. Visit his website. Comment on the blog.

TOPICS: Business/Economy; Government; Miscellaneous; Philosophy

KEYWORDS: anarchism; libertarian; statism; statist

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 ... 561-577 next last

To: justinellis329

I thought that the Founders' biggest worry about a standing army was that it might interfere in politics. Not exactly. They were afraid the government would use a standing army to enforce its will on the people. And it has been used in that way before, just as predicted, though perhaps not as frighteningly as in China. But it's also worth pointing out that a standing police force with paramilitary training fills the role the founders feared of the military.

In other words, if you want to know exactly what the founders feared, look at no-knock and warrantless searches, asset forfeitures, brutality in prisons, etc. Today, we don't even bat an eye when a cop calls non-police "civilians". There was a time when that was seen as a very disturbing trend...

21

posted on

02/20/2006 7:19:10 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: Shalom Israel

"The founders were closer to my view than yours;"

Utter crap! The founders believed in personal responsability. THAT is why they believed in the citizen soldier rather than 'professionals' as a standing army. The founding fathers knew History.

22

posted on

02/20/2006 7:21:36 AM PST

by

TalBlack

(I WON'T suffer the journalizing or editorializing of people who are afraid of the enemies of freedom)

To: Shalom Israel

With SWAT teams and the like, it really is amazing just how much force the state could theoretically use against its citizens. One could argue that great force is necessary to combat new threats like terrorists. But even if so, we need to think carefully about how we use this massive police power we have.

To: Shalom Israel

You are correct......the Founders viewed a standing army as a threat to liberty. The memory of the British soldiers in their midst was fresh....and the second amendment was written as it was "A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed." to recognize the fact that the common defense was to be provided by the whole of the people. There was likewise a very healthy distrust of the FEDERAL government that was to be created. The concern was that it was going to be all powerful and essentially crush the individual states. The second amendment, when viewed with in the context of history, is fully comprehensible:

"A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state".......meant that the whole of the people were to be armed....so that they could defend themselves and their states from enemies foreign and domestic.

24

posted on

02/20/2006 7:26:41 AM PST

by

Conservative Goddess

(Politiae legibus, non leges politiis, adaptandae)

To: Badray

25

posted on

02/20/2006 7:27:02 AM PST

by

Conservative Goddess

(Politiae legibus, non leges politiis, adaptandae)

To: DugwayDuke

Since service in the milita was compulsory (the militia consisted of all able bodied males), how is this consistent with the libertarian philosophy? Libertarian philosophy holds that the preservation of individual liberty is in the best long term interest of the nation. Collective action that directly serves that goal is well within libertarian philosophy. It is anathema to libertarianism when it becomes detrimental to that goal.

26

posted on

02/20/2006 7:28:25 AM PST

by

tacticalogic

("Oh bother!" said Pooh, as he chambered his last round.)

To: justinellis329

>>

Certainly you have to agree there's a difference between a natural right like "the right to property" and a civil right like having X number of people in your jury. From experience, most FReepers don't understand the difference between Natural law and positive law, much less civil law and statutory law.

---------

>>Civil rights just flesh out the details of natural rights; but that doesn't give them the, er, right to trump natural rights.

VERY true. Unfortunately, our government has spent the last 200 or so years trying to blend the multiple law system of our Republic created by the Founders into one 'legal system' of *law* where IT has the unquestioned authority to define all the words.

27

posted on

02/20/2006 7:30:24 AM PST

by

MamaTexan

(I am NOT a ~legal entity~, nor am I a *person* as created by law!)

To: tacticalogic

"Libertarian philosophy holds that the preservation of individual liberty is in the best long term interest of the nation. Collective action that directly serves that goal is well within libertarian philosophy. It is anathema to libertarianism when it becomes detrimental to that goal."

Well, that may be a part of the libertarian philosophy but the Von Mises Institute essentially believes that the government is the most dangerous threat to liberty. Consequently, almost all of the material coming from this Insitute denies any legitimate role for the state and rejects all forms of compulsion. This article specifically rejects any form of collective defense if it is compulsory.

Would you care to explain how a non-compulsory national defense would work?

28

posted on

02/20/2006 7:38:29 AM PST

by

DugwayDuke

(Stupidity can be a self-correcting problem.)

To: justinellis329

My problem is with the author's opening salvo -- that statists "always seem to get it wrong." Such qualified statements are a sure sign that a strawman is soon to follow, and sure enough he gives us one.

To give Our Author credit, he does attempt take on the obvious case of a national defense. Unfortunately, his argument makes no sense ... he basically acknowledges the legitimacy of national defense, then veers off into an odd little discussion of tax rates, and finally never discusses the underlying "statist" notion of a national defense at all.

IOW, the article says nothing -- and indeed it cannot, as to actually tackle the idea of national defense would be to acknowledge the fundamental correctness of a "statist" argument. And thus "almost never" becomes "sometimes", and our author is undone.

29

posted on

02/20/2006 7:44:49 AM PST

by

r9etb

To: DugwayDuke

"National defense cannot be contracted out."

All defense is contracted out now, and that's precisely the problem.

30

posted on

02/20/2006 7:49:50 AM PST

by

VRing

("That every man be armed")

To: Conservative Goddess

You are correct......the Founders viewed a standing army as a threat to liberty. The memory of the British soldiers in their midst was fresh....and the second amendment was written as it was "A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed." to recognize the fact that the common defense was to be provided by the whole of the people. And the hard, hard lesson of the First World War was that lack of a standing army made timely mobilization impossible when large bodies of troops were required. We were lucky, in that war, that we had 9+ months to assemble our troops (who were dismally short of armaments, it must be remembered).

The idea of not having a standing army is fine, so long as one is never seriously threatened by another nation which does have a standing army. To fail to establish a standing army in such cases is to commit suicide.

31

posted on

02/20/2006 7:51:03 AM PST

by

r9etb

To: DugwayDuke

Well, that may be a part of the libertarian philosophy but the Von Mises Institute essentially believes that the government is the most dangerous threat to liberty. Consequently, almost all of the material coming from this Insitute denies any legitimate role for the state and rejects all forms of compulsion. This article specifically rejects any form of collective defense if it is compulsory. If the Von Mises Institute is mis-representing libertarinaism, then the question is about the institute itself, not libertarianism.

Would you care to explain how a non-compulsory national defense would work?

Probably not very well, but the article doesn't seem to be limited to consideration of what is required to provide for the national defense, and I don't think there's a case to be made that any action that is justified in the name of national defense is equally justifiable for any other reason.

32

posted on

02/20/2006 7:53:36 AM PST

by

tacticalogic

("Oh bother!" said Pooh, as he chambered his last round.)

To: VRing

"All defense is contracted out now, and that's precisely the problem."

Would you care to name the contractor that employes the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines?

33

posted on

02/20/2006 7:53:39 AM PST

by

DugwayDuke

(Stupidity can be a self-correcting problem.)

To: DugwayDuke

That would be trying to prove a negative. No, it wouldn't; it's equivalent to proving that defense must be run by the state. If you did some homework, you'd find out that the arguments for state-run defense are very thoroughly expounded out there. I would expect you to counter with that argument, or at least demonstrate some familiarity with it.

The going argument is that of Samuelson, who argues that defense is a "public good." A "public good" is defined to be something that is (1) non-excludable, and (2) non-rivalrous. The former means that you can't prevent free-loaders from being defended. The latter means that my benefiting from defense in no way diminishes your benefit from defense--or, crudely, "defense" is not a "scarcity good".

The rationale behind that argument is two-fold. First, non-excludability implies that free-loaders can refuse to pay for defense, but the defenders are forced to defend them anyway. Thus, people will not pay enough to bear the cost of defense (unless the government forces them to do so). Second, non-rivalry means that it is somehow "inefficient" to allow people to be undefended, since defending them doesn't diminish anyone else's defense. In effect, it's "inefficient," or "wasteful," or "harmful to society," if non-rivalrous goods aren't distributed to everyone who wants them. These arguments are considered so water-tight, that "national defense" is generally cited as the "purest" example of a public good.

The argument is pure buncombe.

First, excludability. Defense is not "perfectly" excludable, it's true. If my defense contractor ends the war by conquering the Mexican invaders, non-subscribers benefit from that. But it is certainly possible to exclude people. For example, a defense contractor might provide an air-raid shelter; non-subscribers can be refused entry. If in some town nobody subscribes, then my defense contractor won't defend that town, unless it happens to be in its subscribers' interest for strategic reasons. The contractor will conduct rescue missions, but only to rescue subscribers. And so on.

Second, non-rivalry. If a rescue squad comes for me, they might (or might not) rescue non-subscribers imprisoned with me; that's a non-rivalrous situation, if there are seats left in the rescue vehicle. More generally, however, defense is certainly rivalrous. Defense takes resources. Mobilizing here reduces defensive manpower over there. There are only so many guns and so much ammunition to go around.

What don't you try to prove that it can be? ... Defense of one's life, liberty, and personal property is not national defense.

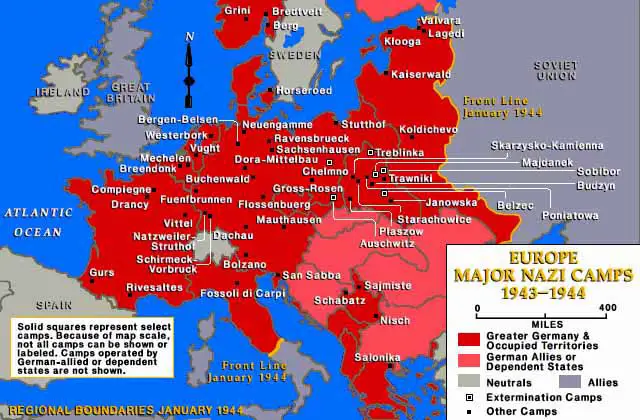

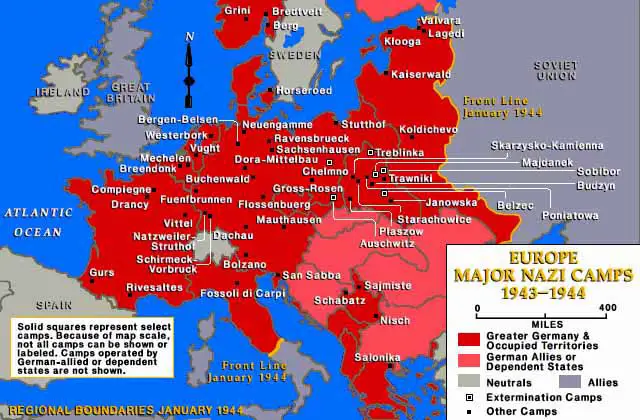

The founders disagreed with you. Those minutemen at Lexington and Concord were fighting to defend their lives, liberty and property. If every citizen is armed and ready to fight, to the last man, in self defense, then the nation is well protected indeed. The invading Canadian army will run into a solid wall of armed citizenry. There's a reason Switzerland wasn't invaded in WWII, you know. The Nazis owned everything between Spain and Russia--except Switzerland.

Take Three guesses: Can you spot Switzerland?

Since service in the milita was compulsory...

I look forward to your proof of that statement. But before you wear yourself out, here's a free clue: Pennsylvania was just crawling with Quakers.

34

posted on

02/20/2006 7:58:06 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: justinellis329

I don't think my argument would justify Kelo...I'm sure you're against Kelo. The irony here is that the state, supposedly indispensible to protecting my rights, is in fact the biggest threat to my rights that there is.

35

posted on

02/20/2006 8:00:15 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: TalBlack

Utter crap! The founders believed in personal responsability. You just said, "You're wrong! You're right..."

36

posted on

02/20/2006 8:01:02 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: Conservative Goddess

I think I'm in love. Sigh. If I were younger, thinner and single...

37

posted on

02/20/2006 8:02:09 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: r9etb

And the hard, hard lesson of the First World War was that lack of a standing army made timely mobilization impossible when large bodies of troops were required.Just an observation: if every capable citizen, male and female, is armed, then there's no "mobilization" required. It's true that it would be impossible to go around invading other countries without assembling an army, though...

38

posted on

02/20/2006 8:05:29 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

To: DugwayDuke

"Would you care to name the contractor that employes the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines?"

The US Government. Duh.

Your turn. Who's the contractor that is responsible for the defense of "my" property?

39

posted on

02/20/2006 8:05:36 AM PST

by

VRing

("That every man be armed")

To: r9etb

My problem is with the author's opening salvo -- that statists "always seem to get it wrong." Such qualified statements are a sure sign that a strawman is soon to follow...Out of curiosity, if I said, "Pedophiles always get it wrong..." exactly what straw-man would you expect me to follow up with? (Also note that "statist" and "minarchist" are two very different things.)

40

posted on

02/20/2006 8:06:51 AM PST

by

Shalom Israel

(Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.)

Navigation: use the links below to view more comments.

first previous 1-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80 ... 561-577 next last

Disclaimer:

Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual

posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its

management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the

exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.

FreeRepublic.com is powered by software copyright 2000-2008 John Robinson

In a recent article, Carl Milsted uses Rothbard to argue it would be permissible to use force to make people pay for a service of which their benefit is at least double its cost. His conclusion is that it is reasonable, and even preferable, to establish a minimalist state if it is to people's advantage.

In a recent article, Carl Milsted uses Rothbard to argue it would be permissible to use force to make people pay for a service of which their benefit is at least double its cost. His conclusion is that it is reasonable, and even preferable, to establish a minimalist state if it is to people's advantage.