Posted on 2/8/2005, 11:50:43 AM by PatrickHenry

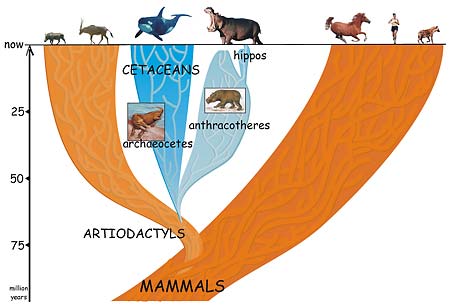

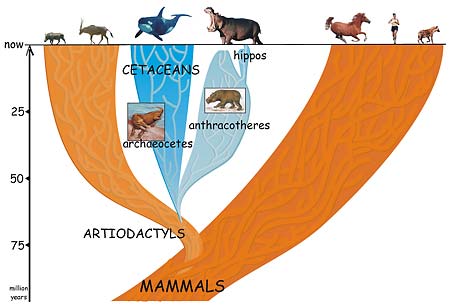

A group of four-footed mammals that flourished worldwide for 40 million years and then died out in the ice ages is the missing link between the whale and its not-so-obvious nearest relative, the hippopotamus.

The conclusion by University of California, Berkeley, post-doctoral fellow Jean-Renaud Boisserie and his French colleagues finally puts to rest the long-standing notion that the hippo is actually related to the pig or to its close relative, the South American peccary. In doing so, the finding reconciles the fossil record with the 20-year-old claim that molecular evidence points to the whale as the closest relative of the hippo.

"The problem with hippos is, if you look at the general shape of the animal it could be related to horses, as the ancient Greeks thought, or pigs, as modern scientists thought, while molecular phylogeny shows a close relationship with whales," said Boisserie. "But cetaceans – whales, porpoises and dolphins – don't look anything like hippos. There is a 40-million-year gap between fossils of early cetaceans and early hippos."

In a paper appearing this week in the Online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Boisserie and colleagues Michel Brunet and Fabrice Lihoreau fill in this gap by proposing that whales and hippos had a common water-loving ancestor 50 to 60 million years ago that evolved and split into two groups: the early cetaceans, which eventually spurned land altogether and became totally aquatic; and a large and diverse group of four-legged beasts called anthracotheres. The pig-like anthracotheres, which blossomed over a 40-million-year period into at least 37 distinct genera on all continents except Oceania and South America, died out less than 2 and a half million years ago, leaving only one descendent: the hippopotamus.

This proposal places whales squarely within the large group of cloven-hoofed mammals (even-toed ungulates) known collectively as the Artiodactyla – the group that includes cows, pigs, sheep, antelopes, camels, giraffes and most of the large land animals. Rather than separating whales from the rest of the mammals, the new study supports a 1997 proposal to place the legless whales and dolphins together with the cloven-hoofed mammals in a group named Cetartiodactyla.

"Our study shows that these groups are not as unrelated as thought by morphologists," Boisserie said, referring to scientists who classify organisms based on their physical characteristics or morphology. "Cetaceans are artiodactyls, but very derived artiodactyls."

The origin of hippos has been debated vociferously for nearly 200 years, ever since the animals were rediscovered by pioneering French paleontologist Georges Cuvier and others. Their conclusion that hippos are closely related to pigs and peccaries was based primarily on their interpretation of the ridges on the molars of these species, Boisserie said.

"In this particular case, you can't really rely on the dentition, however," Boisserie said. "Teeth are the best preserved and most numerous fossils, and analysis of teeth is very important in paleontology, but they are subject to lots of environmental processes and can quickly adapt to the outside world. So, most characteristics are not dependable indications of relationships between major groups of mammals. Teeth are not as reliable as people thought."

As scientists found more fossils of early hippos and anthracotheres, a competing hypothesis roiled the waters: that hippos are descendents of the anthracotheres.

All this was thrown into disarray in 1985 when UC Berkeley's Vincent Sarich, a pioneer of the field of molecular evolution and now a professor emeritus of anthropology, analyzed blood proteins and saw a close relationship between hippos and whales. A subsequent analysis of mitochondrial, nuclear and ribosomal DNA only solidified this relationship.

Though most biologists now agree that whales and hippos are first cousins, they continue to clash over how whales and hippos are related, and where they belong within the even-toed ungulates, the artiodactyls. A major roadblock to linking whales with hippos was the lack of any fossils that appeared intermediate between the two. In fact, it was a bit embarrassing for paleontologists because the claimed link between the two would mean that one of the major radiations of mammals – the one that led to cetaceans, which represent the most successful re-adaptation to life in water – had an origin deeply nested within the artiodactyls, and that morphologists had failed to recognize it.

This new analysis finally brings the fossil evidence into accord with the molecular data, showing that whales and hippos indeed are one another's closest relatives.

"This work provides another important step for the reconciliation between molecular- and morphology-based phylogenies, and indicates new tracks for research on emergence of cetaceans," Boisserie said.

Boisserie became a hippo specialist while digging with Brunet for early human ancestors in the African republic of Chad. Most hominid fossils earlier than about 2 million years ago are found in association with hippo fossils, implying that they lived in the same biotopes and that hippos later became a source of food for our distant ancestors. Hippos first developed in Africa 16 million years ago and exploded in number around 8 million years ago, Boisserie said.

Now a post-doctoral fellow in the Human Evolution Research Center run by integrative biology professor Tim White at UC Berkeley, Boisserie decided to attempt a resolution of the conflict between the molecular data and the fossil record. New whale fossils discovered in Pakistan in 2001, some of which have limb characteristics similar to artiodactyls, drew a more certain link between whales and artiodactyls. Boisserie and his colleagues conducted a phylogenetic analysis of new and previous hippo, whale and anthracothere fossils and were able to argue persuasively that anthracotheres are the missing link between hippos and cetaceans.

While the common ancestor of cetaceans and anthracotheres probably wasn't fully aquatic, it likely lived around water, he said. And while many anthracotheres appear to have been adapted to life in water, all of the youngest fossils of anthracotheres, hippos and cetaceans are aquatic or semi-aquatic.

"Our study is the most complete to date, including lots of different taxa and a lot of new characteristics," Boisserie said. "Our results are very robust and a good alternative to our findings is still to be formulated."

Brunet is associated with the Laboratoire de Géobiologie, Biochronologie et Paléontologie Humaine at the Université de Poitiers and with the Collège de France in Paris. Lihoreau is a post-doctoral fellow in the Département de Paléontologie of the Université de N'Djaména in Chad.

The work was supported in part by the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Tchadienne, which is co-directed by Brunet and Patrick Vignaud of the Université de Poitiers, and in part by funds to Boisserie from the Fondation Fyssen, the French Ministère des Affaires Etrangères and the National Science Foundation's Revealing Hominid Origins Initiative, which is co-directed by Tim White and Clark Howell of UC Berkeley.

Excuse my bad on angular momentum. However the rest is correct.

Nevertheless, b_sharp is right about what happens when you fire your nose rockets to slow down. That is, you drop into a lower orbit and actually gain velocity. The delta vee comes from your fall from altitude. You trade potential energy (your altitude) for kinetic (your velocity).

Firing your main engine indeed boosts you into a higher orbit and a lower velocity. Against that, you have a higher potential energy. Overall, the higher orbit means you have more energy to get rid of when you try to re-enter. (You could ask the last shuttle crew about that problem, but they can't answer.)

The creationist's DU.

I corrected just before your post.

A little more complicated as you change from a circular to elliptical orbit.

You have to make adjustments to get to the new circular orbit.

In a circular orbit, the tangential velocity is related to the value of g which varies with altitude.

In this case, the rocket goes into an elliptical orbit with a periapsis closer to the earth and a faster speed at the periapsis (but the same (slower) speed at the apoapsis. Once the rocket reaches the periapsis, the rockets can be fired to adjust the speed that is required for the new lower circular orbit.

In the scientific community, or in the general populace? What does the general populace know about evolution? Probably only what their pastors tell them.

Does the general populace understand the basic issues surrounding ID vs. Evo? No. So their opinion doesn't matter in determining whether it's a reasonable or scientific view.

If a person cannot explain the "irreducible complexity" argument, and why evolutionists discount the "irreducible complexity" argument, they aren't worth listening to about evolution. (note that the ability to explain an argument does not mean that you have to support that argument; I'm not demanding that people support evolution in order for their views to be valid)

Thanks for the verification. I will save this little gem since I have heard it so few times. It's nice for an old man to remember something more or less correct from his past.

That was before corrections were made in 2125 and 2128.

Firing the retro does not drop you to a lower orbit. It puts you into an elliptical orbit with the apoapsis at the same altitude and the rocket at slower velocity at that point.

A survey found that 45% of the US population believes that a bullet fired from a curved barrel will continue to curve after leaving the barrel.

About half the general public accepts evolution.

If a person cannot explain the "irreducible complexity" argument, and why evolutionists discount the "irreducible complexity" argument,

Can you explain why evolutionists discount the "irreducile complexity" argument?

Because it has been thoroughly debunked and is now accepted only by ID freaks.

Yes! As a matter of fact, I can.

Other people can do it better, but I can still do it.

"Irreducible complexity" can actually be defined somewhat objectively, which puts it a step up over other creationist nonsense. Anything that is "irreducibly complex" is that which is made up of multiple parts, and its function cannot take place if any of those parts is missing. We still don't know exactly what a "part" is (if it's "anything such that the machine can't function without it" it would be a tautological definition, which is why I say IC is only somewhat objective)

In other words, if there are five pieces in a machine, and I remove any one of those pieces, the machine would not be able to function. Therefore, that machine would be irreducibly complex. Presumably, things that required twenty functioning pieces would be more complex than those that required only five, but all would be irreducibly complex.

Michael Behe is the main proponent of Irreducible Complexity as the Darwin-killing theory that proves evolution is just not possible, even given the existence of micro-evolution. It is important to note that Behe says that IC still can't evolve, even from micro-evolution (which means he accepts micro-evolution as a premise for his argument, which means evolutionists can assume it as well).

Imagine if you will, the following map:

Key:

Grass: .

Water: w

Town A: A

Town B: B

................... ................... .......ww.......... ......wwww......... ...A..wwww..B...... ......wwww......... .......ww.......... ...................

You might say, there is no way to walk from town A to town B, because there is a lake in the middle. In fact, an "as the crow flies" route would be impossible to walk.

This is basically what Behe claims, that there is no direct way for the distinct elements of an irreducibly complex system to evolve, because on their own, the elements would not benefit the organisms until all of them are in place.

But this argument is rejected on a number of grounds. For one, the components of an irreducibly complex system are not necessarily useless by themselves. Often they serve some other fuction. See, for example, the bacterial flagellum, whose base is the same as a cytotoxin pump.

Another reason to reject "irreducible complexity" is that not all evolution takes the direct route. For instance, to get from town A to town B, maybe you would walk to the north of the lake. Likewise, IC systems might evolve by first developing as overly complicated systems with redundancy in them, and only later lose that extra complexity once the system's basic function was in place. In other words, the IC system's function would have been carried out by a non-IC system before evolutionary pressures favored mutations that led to the less complex IC system. It's easier to imagine IC systems evolving from overly-complex systems that already have the function in question than evolving from scratch.

In fact, software designed by evolutionists (design, ha ha ha, laff it up, it's illogical but have your laff) suggests that an Irreducibly Complex algorithm can be the result of small, incremental evolutionary changes similar to micro-evolution (which Michael Behe accepts when he says that IC systems cannot evolve from micro-evolution). In other words, both logic and scientific experiments show that IC can be achieved through micro-evolution.

Okay, now it's your turn :-)

No. A system is irreducibly complex if it contains two or more interrelated parts that cannot be simplified without destroying the system’s basic function.

We still don't know exactly what a "part" is (if it's "anything such that the machine can't function without it" it would be a tautological definition, which is why I say IC is only somewhat objective)

It may require some thought but it's not tautological.

In other words, if there are five pieces in a machine, and I remove any one of those pieces, the machine would not be able to function.

No, you don't quite grasp it.

See, for example, the bacterial flagellum, whose base is the same as a cytotoxin pump.

That was the widely publicized rebuttal. It doesn't explain the flagellum motor AND evolutionary biologist think the TTSS evolved from the flagellum.

Another reason to reject "irreducible complexity" is that not all evolution takes the direct route.

Good. We're rejecting the direct Darwinian path. That's out of the road. The problem with the indirect route is that multiple protein parts from different functional systems have to coalesce to form a newly integrated system. That's fantastically unlikely. Anyway there is no evidence of it -- unless you take the position that evolution is true so it must have happened that way, which is kind of like what you are accusing us of doing.

In fact, software designed by evolutionists

Software designed by environmentalists show the ice caps melting and New York underwater. Data in, wishes out.

If you wrote your response without cutting and pasting you have my sincere compliments.

Two or more --> multiple

cannot be simplified without destroying the system's basic function --> its function cannot take place if any of those parts is missing

How is my definition inadaequate?

That was the widely publicized rebuttal. It doesn't explain the flagellum motor AND evolutionary biologist think the TTSS evolved from the flagellum.

Why should it have to? It's already established that there is some function even with most of the parts missing! Since that is true, the flagellum cannot be considered IC, even though it used to be one of the prime examples of an IC system.

The problem with the indirect route is that multiple protein parts from different functional systems have to coalesce to form a newly integrated system.

Yeah. But the fact that the individual "parts" (such a scientific term) generally have other functions within the cell gives a reason for them to be there in the first place, to be combined.

Software designed by environmentalists show the ice caps melting and New York underwater. Data in, wishes out.

The expression is "garbage in, garbage out," as in: if you put bad data in, you get bad data out. I'll point out that the software in question is premised only on things that Michael Behe admits (microevolution through random mutations) while he says IC systems cannot evolve. It has shown that microevolution can lead to IC systems. It's a major finding.

It's not a matter of something of multiple parts but of multi parts that can't be simplified without destroying its function. A car has multiple parts but you can remove the trunk lid or radio and it will function. An irreducible car would be the motor, driveshaft, axles, wheels and fuel source.

Without either the propeller, shaft or motor, the flagellum won't function.

Why should it have to?

Why should the TTSS come after the flagellum? It's standard evolutionary theory. Evolutionary biologist think the flagellum has been around for 2-3 billion years. The TTSS is a delivery system for pathogens to multi-celled life which, according to evo biologist have been around for just 600 million years. You're not suggesting that TTSS popped up without a purpose, evolved into the flagellum, then found its role?

Blasted placemarker.

My question about IC is why someone would design a machine that would have parts not essential to function?

The only thing I could think of were safety guards etc. You can remove them and the machine still functions, but someone could get hurt.

In any case, IC is circular in much of its reasoning. It does not anticipate increments in ability to function.

Some parts are not necessary for function, but make the machine more efficient, like the front sights on a handgun.

To be even more specific, Michael Behe (the main IC guy) would agree that if handguns were like bacteria, they could probably evolve their own front sights, but they couldn't evolve something irreducibly complex like the semi-auto loading mechanism, he would say that must be the result of design. (in the case of a handgun, he'd be right, of course)

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.