Posted on 04/12/2004 7:53:52 AM PDT by Valin

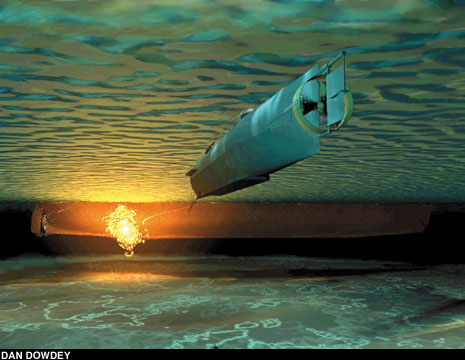

The identities of the crew of the Civil War submarine H.L. Hunley are coming to light just days before the mens remains are to be buried. The first submarine to sink an enemy ship, the Hunley itself sank off South Carolina in 1864, was found in 1995, and was raised in 2000. On a cold February night in 1864, eight men squeezed through the tiny hatches of the H.L. Hunley, a strange new warship tied up at a dock in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. They crawled or duckwalked through the 4-foot-tall (1.2-meter-tall) passageway to their places on a long, low bench. Each of them sat down at a hand crank attached to the Hunley's propeller shaft.

These eight men were the living power plant for a revolutionary machine—a submarine that could attack an enemy ship from underwater. Led by Confederate Lt. George Dixon, these men would literally dive into the pages of history when the submerged Hunley attached a torpedo to the U.S.S. Housatonic and blew it up. The Union warship was helping to enforce the maritime blockade of Charleston that was slowly strangling the rebellious Confederate States of America's ability to fight the Civil War.

(Clay covering the cast of a skull was used to reconstruct the face of one of the crewmen of the Civil War submarine Hunley. (See more photos.) In the four years since the sub's recovery from the bottom of a South Carolina harbor, a team of experts has undertaken a massive effort to reconstruct not only the faces of the crew but also their stories.

The researcher's findings were revealed on the National Geographic Ultimate Explorer documentary that aired on April 11 on MSNBC TV.

Get a 3-D interactive view of the H. L. Hunley and read an online excerpt from National Geographic magazine's July 2002 article "The H.L. Hunley: Secret Weapon of the Confederacy.")

But the cantankerous Hunley was as dangerous to its crew as it was to the Housatonic, and not long after the Union warship sank, the submarine slipped to the bottom of the bay and never came up.

The name of the first submarine to sink an enemy vessel became the stuff of legend. With the exception of Dixon, however, the names of most of the crewmen who propelled the Hunley to glory were obscured by the mists of time.

That's now changed. After years of painstaking work, a team of archaeologists, forensic experts, and researchers at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in Charleston has dug up some interesting information—and more than a few surprises—about the submarine and the crewmen who had rested 30 feet (10 meters) below the surface of the ocean since 1864. These details were revealed on April 11 in a National Geographic Ultimate Explorer documentary produced by Simon Boyce.

Friends of the Hunley

The Hunley was found in 1995 by underwater archaeologists working for author Clive Cussler. South Carolina officials created the Hunley Commission to recover, preserve, and display the historic warship, and a private group, Friends of the Hunley, was formed to help with the project.

The submarine was raised in August 2000, and in January 2001 the investigators went to work. The team included forensic experts Doug Owsley and Sharon Long, archaeologist Maria Jacobsen, genealogist Linda Abrams, and underwater archaeologist Harry Pecorelli III.

They carefully removed the silt that had filled—and helped preserve—the Hunley, and recovered the remains of the crew. The forensic experts examined the bones and teeth for clues about the crew's identity. Long, a forensic sculptor, used the skulls to recreate faces of the men who had been lost to time.

One of the striking facts revealed by the research is that the men who went down with the Hunley reflected the complex loyalties, divisive politics, and slavery disputes that pulled the United States apart in the middle of the 19th century.

Most of the men aboard the submarine weren't from any of the 11 southern slaveholding states that made up the short-lived Confederate States of America. Four were probably from northern Europe. One was from Maryland, a slaveholding state that didn't secede from the United States when the Civil War erupted in 1861.

Two crewmen were from slaveholding states that had withdrawn from the Union. And George Dixon—who led the Hunley on its historic but doomed mission and became an immortal hero for the Confederacy—was from Ohio, where slavery was illegal.

The researchers identified the four likely Europeans by finding clues about their diets from their teeth. Uncovering the names of the Europeans has been difficult, but the researchers have developed some theories about their lives before they joined the Confederate cause.

Life of Strenuous Toil

The battered skull of one of the Europeans—a man in his early 40s who was perhaps named Simkins or Lumkin—revealed that he was a brawler who had been in some intense fights before he became a crewman on the Hunley.

Another European was a young man of about 20, perhaps named Arnold Becker, who may have been from Germany. Becker's spine showed that, despite his young age, he'd already lived a life of strenuous toil, lifting very heavy loads.

One of the Europeans was a man in his mid-40s whose name may have been Miller. The fourth non-American, who could have been named Carlsen, was a daring man who had made a lot of money by running supplies for the Confederate States through the Union blockade of southern ports.

The two men from seceded states were James Wicks from North Carolina and Frank Collins from Virginia. Wicks, who was about 40, was serving in the United States Navy when the war broke out. But when his ship was sunk in fighting at Hampton Roads, Virginia, Wicks joined the Confederate Navy.

James Ridgaway was from Talbot County, Maryland. He carried a war souvenir that puzzled the researchers for a while—an identification tag belonging to Ezra Chamberlain, a Union soldier from Connecticut. Researchers thought at first that they'd discovered a Union deserter serving on the Hunley, but later determined that Ridgaway was carrying the tag that apparently had been taken from Chamberlain's body after he'd been killed in battle.

The fact that George Dixon came from Ohio was only one of several surprises uncovered about the Hunley's commander. After the war, a colorful legend arose about him.

Lucky Gold Coin Dixon, so the story went, had a beautiful young sweetheart in Mobile, Alabama, named Queenie Bennett. She gave him a U.S. $20 gold piece, which Dixon had in his pocket at the bloody Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee in 1862.

A bullet that could have killed Dixon struck him in the thigh, but the gold coin stopped the slug. The legend said that Dixon had this lifesaving coin from his sweetheart with him the night he went down with the Hunley.

Bennett had a photograph supposedly of Dixon that was published many times after the Civil War.

A bent gold coin, inscribed "Shiloh April 6, 1862 My life Preserver G.E.D" was found in the Hunley near Dixon's remains. At least part of the legend was true. But there was no mention of Queenie Bennett in the inscription, and when investigator Nick Herrmann used a laser to examine Dixon's skull, another surprise was revealed. The man in the photo that Bennett had kept probably was not George Dixon.

The researchers in Charleston also have discovered that the Hunley was even more of an engineering marvel that anyone had realized. Pecorelli, the underwater archaeologist who found the submarine with diver Wes Hall in 1995, said the submarine is "almost a work of art."

The men who built the Hunley gave the warship's prow a knifelike shape that would cut through the water, and the rivets that held the ship together were sunk flush with the hull to reduce drag. "We could see right off the bat that someone had spent a lot of time putting this thing together," Pecorelli said.

Still, one question about the Hunley's fate has only been deepened by its discovery. Whatever caused the submarine to sink is still a mystery. The researchers discovered that the crewmen were still seated at their posts when they died.

It was a puzzling discovery. "You'd expect that when the sub flooded, they'd have desperately tried to escape," Boyce, the National Geographic television producer, said. "There's no evidence of that."

Pecorelli is confident that the crew's remains will yield an answer as to why they perished, but finding that answer will take years.

"In the end, we'll be able to answer what happened more accurately than if they brought the Hunley up the next day after it sank," Pecorelli said. "It won't be a guess."

I watched it last night, very interesting. I am sure it will be re-broadcast several times for those who missed it.

free dixie,sw

i was PLEASED!

PLEASE smallcase my screen-name, as i'm just the General's muleholder.<P.free dixie,sw

Fair enough stand.

you and e e cummings

free dixie,sw

free dixie,sw

Five of the men who drowned in this harbor with Capt. Hunley, several weeks ago, were mechanics of the city of Mobile, who have left families in destitute circumstances, having been dependent for support on the wages of the men now taken from them. These families are commended to the attention of the liberal gentlemen of Charleston, as objects worthy of judicious and substantial charity.

Bet they don't put that in the movie.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.