|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

Posted on 03/06/2003 5:33:16 AM PST by SAMWolf

|

are acknowledged, affirmed and commemorated.

|

|

|

|

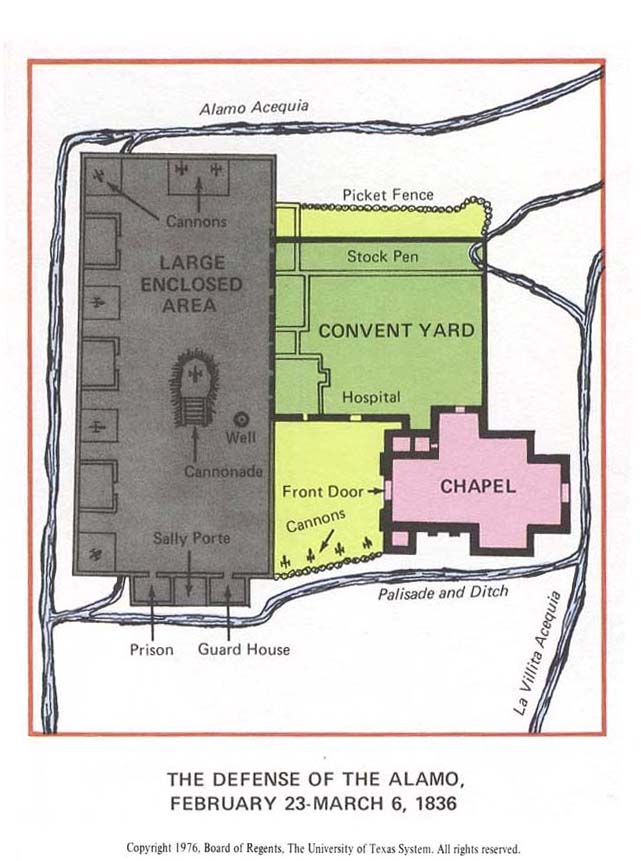

The garrison's sentries spot the advance of Santa Anna's Cavalry units. After scouts confirm the Mexican army's presence, Colonel William B. Travis orders a withdrawal into the Alamo compound.  In a parley with Mexican Colonel Juan Almonte the Texians are ordered to surrender or be put to the sword. Travis answers the Mexican's terms with a volley from the 18-pounder. The second day of the siege began early with the Texians facing a newly established battery erected by the Mexicans during the night. The battery consisted of two eight-pounders and a howitzer and was located approximately 400 yards to the west of the fort. It was known as the River Battery. The defenders were busy that night as well. They had captured at least one Mexican soldier and six pack mules during a nighttime patrol. According to Enrique Esparza, the defenders used the captured soldier to decipher bugle calls for the Texians throughout the siege. Sometime around eleven that morning, Santa Anna began his survey of the Alamo fortifications and surrounding area to familiarize himself with the area. The Mexican army pillaged the Texian's stores in Béxar and began the bombardment of the Alamo in earnest. The Texian artillery returned fire with no obvious results. James Bowie, in command of the garrison, fell ill. The garrion's surgeon described his illness as a "A peculiar disease of a peculiar nature." Jim Bowie relinquished his command of the garrison to Travis.  The Alamo's well proved inadequate in supplying the garrison's water needs. This forced the defenders to obtain water from the acequia and reservoir to east of the compound setting the stage for several skirmishes. Travis penned his "To the people of Texas and all Americans in the world" letter. Defender Albert Martin carried the letter from the Alamo and added his own comments to the back of the document. Historians consider this letter to be one of the most stirring documents in American history because it helped to establish the Texian national identity. The morning of February 25, 1836 dawned with summer-like temperatures opening one of the most eventful days of the siege.  William Barret Travis The Mexicans launched an attack with approximately 400 - 450 soldiers personally led by General Castrillon. The Matamoros Battalion and three companies of cazadores made up the attacking force. They came from the area of the river battery through Pueblo de Valero's jacales and buildings advancing to within 50-100 yards from the Alamo's walls. After two hours of fighting, The Texians finally forced a Mexican withdrawal using the ditches and outworks. They inflicted only light casualties on their attackers. Sometime during the fighting, Texian sorties burned the jacales closest to the Alamo. At the same time, the Mexicans established new fortifications near the McMullen house. As the Mexicans advanced through the pueblo, they discovered a young woman and her mother in one of the houses. Although already married, Santa Anna took advantage of the situation, arranged a false marriage, and quickly consummated the relationship.  That night, the temperatures dropped into the 30's. Under the cover of darkness, William B. Travis sent Colonel Juan Seguin to find General Houston and ask for help. The defenders ventured out again burning even more jacales. There is some evidence that at least nine men deserted the garrison and gave information to Santa Anna where the Texians had hidden at least 50 rifles. The day's fighting was not a victory for the Texians. The Mexicans had established artillery and infantry entrenchments in La Villita and the Alameda, but the Texians proved that as unorganized as they were, they could fight. The Texians burned more jacales during the night. It soon became obvious that the Alamo's water well would not supply the needs of a 150+ people in the garrison. They would have to obtain water from the nearby acequia. The overnight arrival of a norther dropped the temperatures to near freezing. As daylight broke, a Texian foray went outside the walls to obtain water and wood. A small skirmish erupted with the Mexican troops under General Sesma. Mexican casualties were slightly heavier than in earlier fights due to the Texian's eastern-facing cannon. The fifth day of the siege was again cold with temperatures ranging in the 30s. Having exhausted their own supplies, the Mexicans pillaged BŽjar of foodstuffs and perishables. When they in turn depleted these, they sent troops to nearby ranchos to forage livestock and corn.  In a decisive move, the Mexicans cut off the eastern acequia's water supply at its source: the San Antonio River. Not only did this end the minor skirmishes that had taken place from the beginning of the siege; it essentially eliminated the defender's major source of water. The Matamoros battalion began work on trenches to the South of the Alamo compound. These entrenchments did not pass Santa Anna's inspection and so he ordered his men to dig new entrenchments closer to the Alamo under the direct supervision of General Amador. Throughout the day, the Texians maintained constant fire on the Mexican work party. According to General Filisola, the Texians were seen working frantically on their own ditch inside the parapet of the cattle pen. This effort later proved fruitless and was harmful to the Alamo's defense by undermining the walls, essentially removing any walkway the defenders might have had exposing them to Mexican fire. General Gaona received Santa Anna's letter of the 25th requesting him to send three battalions as quickly as possible. Gaona immediately complied, yet failed to forward any heavy siege guns because Santa Anna neglected to include this request in his dispatch. Mexicans receive intelligence that 200 Texian reinforcements from Goliad are en route to the Alamo.  The morale within the compound is high. According to Mrs. Dickinson, Crockett took up a fiddle and challenged John McGregor, a Scot with bagpipes, to a contest of instruments. The Mexican's Jimenez battalion and the cavalry under command of General Ramirez y Sesma are ordered down the Goliad road to intercept any reinforcements that might have been sent by Fannin. The Mexicans propose a three-day armistice and several Tejanos leave Alamo during the cease-fire. Thirty-two reinforcements from Gonzales arrive.  Davy Crockett General Sesma advances towards Goliad to seek out Texian reinforcements coming to the aid of the Alamo. Finding none, he returns to Bexar. The Alamo's 12-pound gunnade fires two shots, one of them hitting Santa Anna's headquarters. Travis receives a report that there is corn at the Seguin ranch. He sends a detatchment headed by Lt. Menchaca to retrieve it. Mexican forces discover a hidden road within pistol shot of the Alamo and post the Jimenez battalion there to cover it. Unknown to the defenders, Independence has been declared at Washington-on-the-Brazos. James Butler Bonham arrives with news of reinforcements. He reports that sixty men from Gonzales are due and that an additional 600 would soon be en route.  The Texians fire several shots into the city in celebration. Santa Anna receives word of Mexican General Urrea's victory at San Patricio. In celebration, the Mexcians ring church bells and there is revelry in the camp. Santa Anna gathers his officers for a council of war. It is decided that when the final assault takes place, that they will take no prisoners. The time for the assault will be determined tomorrow.  Jim Bowie Having been consolidated into two batteries, the Mexican artillery, is brought to within 200 yards of the compound. More Texian reinforcements arrive in the late hours. Santa Anna issues orders for the assault to begin on the following day utilizing four assault columns and one reserve column. Santa Anna calls for reconnaissance to determine Mexican attack positions and approaches. A messenger arrives at the compound with the grim news that reinforcements aren't coming. Travis gathers his men and informs them of their options. At midnight the Mexicans begin moving into attack position.

|

The massed troops moved quietly, encountering the Texian sentinels first. They killed them as they slept.

No longer able to contain the nervous energy gripping them, cries of "Viva la Republica" and "Viva Santa Anna" broke the stillness.

The Mexican soldiers' shouts spoiled the moment of surprise.

Inside the compound, Adjutant John Baugh had just begun his morning rounds when he heard the cries. He hurriedly ran to the quarters of Colonel William Barret Travis. He awakened him with: "Colonel Travis, the Mexicans are coming!" Travis and his slave Joe quickly scrambled from their cots. The two men grabbed their weapons and headed for the north wall battery. Travis yelled "Come on boys, the Mexicans are on us and we'll give them Hell! "Unable to see the advancing troops for the darkness, the Texian gunners blindly opened fire; they had packed their cannon with jagged pieces of scrap metal, shot, and chain. The muzzle flash briefly illuminated the landscape and it was with horror that the Texians understood their predicament. The enemy had nearly reached the walls of the compound.

Travis hastily climbed to the top of the north wall battery and readied himself to fire; discharging both barrels of his shotgun into the massed troops below. As he turned to reload, a single lead ball struck him in the forehead sending him rolling down the ramp where he came to rest in a sitting position. Travis was dead. Joe saw his master go down and so retreated to one of the rooms along the west wall to hide.

There was no safe position on the walls of the compound. Each time the Texian riflemen fired at the troops below, they exposed themselves to deadly Mexican fire. On the south end of the compound, Colonel Juan Morales and about 100 riflemen attacked what they perceived was the weak palisade area. They met heavy fire from Crockett's riflemen and a single cannon. Morales's men quickly moved toward the southwest corner and the comparative safety of cover behind an old stone building and the burned ruins of scattered jacales.

General Castrillón took command from the wounded Colonel Duque and began the difficult task of getting his men over the wall. As the Mexican army reached the walls, their advance halted. Santa Anna saw this lag and so committed his reserve of 400 men to the assault bringing the total force to around 1400 men.

Amid the Texian cannon fire tearing through their ranks, General Cos's troops performed a right oblique to begin an assault on the west wall. The Mexicans used axes and crowbars to break through the barricaded windows and openings. They climbed through the gun ports and over the wall to enter the compound.

General Amador and his men entered the compound by climbing up the rough-faced repairs made on the north wall by the Texians. They successfully breached the wall and in a flood of fury, the Mexican army poured through.

The Texians turned their cannon northward to check this new onslaught. With cannon fire shifted, Colonel Morales recognized a momentary advantage. His men stormed the walls and took the southwest corner, the 18-pounder, and the main gate. The Mexican army was now able to enter from almost every direction.

In one room near the main gate, the Mexican soldiers found Colonel James Bowie. Bowie was critically ill and confined to bed when the fighting began. The soldiers showed little mercy as they silenced him with their bayonets.

The Texians continued to pour gunfire into the advancing Mexican soldiers devastating their ranks. Still they came.

When they saw the enemy rush into the compound from all sides, the Texians fell back to their defenses in the Long Barracks. Crockett's men in the palisade area retreated into the church.

The rooms of the north barrack and the Long Barracks had been prepared well in advance in the event the Mexicans gained entry. The Texians made the rooms formidable by trenching and barricading them with raw cowhides filled with earth. For a short time, the Texians held their ground.

The Mexicans turned the abandoned Texian cannon on the barricaded rooms. With cannon blast followed by a musket volley, the Mexican soldiers stormed the rooms to finish the defenders inside the barrack.

Mexican soldiers rushed the darkened rooms. With sword, bayonet, knife, and fist the adversaries clashed. In the darkened rooms of the north barrack, it was hard to tell friend from foe. The Mexicans systematically took room after room; finally, the only resistance came from within the church itself.

Once more, the Mexicans employed the Texians' cannon to blast apart the defenses of the entrance. Bonham, Dickinson and Esparza died by their cannon at the rear of the church. An act of war became a slaughter. It was over in minutes.

According to one of Santa Anna's officers, the Mexican army overwhelmed and captured a small group of defenders. According to this officer, Crockett was among them. The prisoners were brought before Santa Anna where General Castrillón asked for mercy on their behalf. Santa Anna instead answered with a "gesture of indignation" and ordered their execution. Nearby officers who had not taken part in the assault fell upon the helpless men with their swords. One Mexican officer noted in his journal that: "Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers."

Santa Anna ordered Alcalde Francisco Ruiz to gather firewood from the surrounding countryside and in alternating layers of wood and bodies the dead were stacked.

At 5:00 O'clock in the evening the pyres were lit. In this final act, Santa Anna's "small affair" ended.

From the northwest: General Martín Perfecto de Cós with two hundred fusiliers and rifleman of the Aldama Battalion and one hundred fusilers of the San Luis Potosi militia carrying ten ladders, two crowbars, and two axes.

From the north: Colonel Francisco Duqué with the Toluca Battalion (minus the grenadiers) and three fusilier companies of San Luis, about four hundred men in all, carrying ten ladders, two crowbars, and two axes.

From the northeast: Colonel José María Romero with fusilier companies of the Matamoros and Jimenez battalions, about thre hundred men, carrying six ladders.

From the south: Colonel Juan Morales with three rifle companies of the Matamoros, Jimenez, and San Luis battalions, totaling one hundred men, carrying two ladders.

Mauled by Alamo artillery and small-arms fire, the columns on the east, north, and west waver and fall back. The southeren column seeks shelter behind the jacales at the southwest corner.

Meanwhile, General Castrillón directs the assault of the north column up the wooden outerwork that covers the entire face of the north wall, but his men meet fierce resistance.

Santa Anna then sends in the reserves: the Zapadores Battalion and five grenadier companies of Matamoros, Jimenez, Aldama, Toluca, and San Luis, 400 men in all.

Seeing their flanks exposed by the ingress of the columns under Cos and Romero, the Texians defending the north wall abandon it and seek shelter in the second line of defense: the long barracks and other houses within the compound.

By this time Morales's men have also entered the fort, seizing the eighteen-pounder and the main gate positions. Mexican soldiers now pour unchecked into the Alamo from almost every direction. In the barracks and the chapel, the surviving Texians ensconce themselves for their last, brutal stand.

| 'Commandancy of the Alamo Bexar, Feby. 24th, 1836 To the People of Texas & all Americans in the World-- Fellow Citizens and Compatriots-- I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna--I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man--The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken--I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls--I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all despatch--The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country--Victory or Death.' -- William Barret Travis Lt. Col. comdt.

Let the old men tell the story Let the legend grow and grow Of the 13 days of glory At the siege of Alamo. Lift the tattered banners proudly While the eyes of Texas shine Let the fort that was a mission Be an everlasting shrine. That they died to give us freedom That is all we need to know Of the 13 days of glory At the siege of Alamo. -- "The Alamo",1960 |

| Standing Operating Procedures state: Click the Pics  |

It is difficult to recall that stouthearted men such as Davy Crockett, Will Travis, and Jim Bowie really existed. These were real men with real dreams and real desires. Real blood flowed in their veins. They loved their families and enjoyed life (Travis was only 23 years old) as much as any of us. There was something different about them, however. They possessed a commitment to liberty that transcended personal safety and comfort.

"Liberty" is an easy word to say, but it is a hard word to live up to. Freedom has little to do with financial gain or personal pleasure. Freedom brings with her an unattractive companion called "Responsibility." Neither is she an only child. "Patriotism" and "Morality" are her sisters. They are inseparable. Destroy one and all will die.

Early in the siege, Travis wrote these words to the people of Texas: "Fellow Citizens & Compatriots: I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot & our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. VICTORY OR DEATH! P.S. The Lord is on our side."

As you read those words, remember that Travis and the others did not have the Anti-Christian Liberties Union, the People for the un-American Way, and the National Education Association telling them how intolerant and narrow-minded their notions of honor and patriotism were. A hostile media did not constantly castigate them as a bunch of wild-eyed extremists. As school children, they were not taught that their forefathers were nothing more than racist jerks.

The brave men at the Alamo labored under the belief that America (and Texas) really was "the land of the free and the home of the brave." They believed God was on their side and that the freedom of future generations depended on their courage and resolve. They further believed their posterity would remember their sacrifice as an act of love and devotion. It all looks pale now.

By today's standards, the gallant men of the Alamo seem rather foolish. After all, they had no chance of winning - none! However, the call for "pragmatism" and "practicality" was never sounded. The clarion call they answered was, "VICTORY OR DEATH!"

Please try to remember the heroes of the Alamo as you listen to our gutless political (and religious) leaders calling for appeasement, compromise, and tolerance. Try to recall the time in this country when ordinary men (and women) had the courage of their convictions and were willing to sacrifice their lives on the altar of freedom and principle.

I'll tell you this, those courageous champions didn't die for any political party or for some ambiguous "lesser of two evils" mantra! They fought and died for a principle! So did the men at Lexington and Concord. That is our history. On second thought, do they look foolish, or do we?

Today's classic warship, USS Enterprise

Enterprise class schooner

Tonnage. 135

Lenght. 84'7"

Beam. 22'6"

Draft. 10'

Complement. 70

Armament. 12 6 pdr.

The USS Enterprise, a schooner, was built by Henry Spencer at Baltimore, Md., in 1799, and placed under the command of Lieutenant John Shaw.

On 17 December 1799, Enterprise departed the Delaware Capes for the Caribbean to protect United States merchantmen from the depredations of French privateers during the Quasi-War with France. Within the following year, Enterprise captured 8 privateers and liberated 11 American vessels from captivity, achievements which assured her inclusion in the 14 ships retained in the Navy after the Quasi-War.

Enterprise next sailed to the Mediterranean, raising Gibraltar on 26 June 1801, where she was to join other U.S. warships in writing a bright and enduring page in American naval history. Enterprise's first action came on 1 August 1801 when, just west of Malta, she defeated the 14-gun Tripolitan corsair Tripoli, after a fierce but one-sided battle. Unscathed, Enterprise sent the battered pirate into port since the schooner's orders prohibited taking prizes. Her next victories came in 1803 after months of carrying despatches, convoying merchantmen, and patrolling the Mediterranean. On 17 January, she captured Paulina, a Tunisian ship under charter to the Bashaw of Tripoli, and on 22 May, she ran a 30-ton craft ashore on the coast of Tripoli. For the next month, Enterprise and other ships of the squadron cruised inshore bombarding the coast and sending landing parties to destroy enemy small craft.

On 23 December 1803, after a quiet interval of cruising Enterprise joined with the frigate Constitution to capture the Tripolitan ketch Mastico. Refitted and renamed Intrepid, the ketch was given to Enterprise's commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr., for use in a daring expedition to burn frigate Philadelphia, captured by the Tripolitans and anchored in the harbor of Tripoli. Decatur and his volunteer crew carried out their mission perfectly, destroying the frigate and depriving Tripoli of a powerful warship. Enterprise continued to patrol the Barbary Coast until July 1804 when she joined the other ships of the squadron in general attacks on the city of Tripoli over a period of several weeks.

Enterprise passed the winter in Venice, where she was practically rebuilt by May 1805. She rejoined her squadron in July, and resumed patrol and convoy duty until August of 1807. During that period she fought (15 August 1806) a brief engagement off Gibraltar with a group of Spanish gunboats who attacked her but were driven off. Enterprise returned to the United States in late 1807, and cruised coastal waters until June 1809. After a brief tour of the Mediterranean, she sailed to New York, where she was laid up for nearly a year.

Repaired at the Washington Navy Yard, Enterprise was recommissioned there in April 1811, then sailed for operations out of Savannah, Ga., and Charleston, S.C. She returned to Washington for extensive repairs and modifications; when she saied on 20 May 1812, she had been refitted as a brig. At sea when war was declared on Great Britain, she cruised along the east coast during the first year of hostilities. On 5 September 1813, Enterprise sighted and chased HBM Brig Boxer. The brigs opened fire on each other, and in a closely fought, fierce and gallant action which took the lives of both commanding officers, Enterprise captured Boxer and took her into nearby Portland, Maine. Here, a common funeral was held for Lieutenant William Burrows, Enterprise, and Captain Samuel Blyth, Boxer, both well known and highly respected in their services.

After repairing at Portland, Enterprise sailed in company with the brig Rattlesnake, for the Caribbean. The two ships took three prizes before bing forced to separate by a heavily armed ship on 25 February 1814. Enterprise was compelled to jettison most of her guns in order to outsail her superior antagonist. The brig reached Wilmington, N.C., on 9 March 1814, then passed the remainder of the was as a guardship off Charleston, S.C.

Enterprise served one more short tour in the Mediterranean (July-November 1815), then cruised the northeastern seaboard until November 1817. From that time on, she sailed the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, suppressing pirates, smugglers, and slavers; in this duty she took 13 prizes, including 4 pirate ships in one day on March 6, 1822.

Her long career ended on 9 July 1823, when, without injury to her crew, she stranded and broke up on Little Curacao Island in the West Indies.

Bimbo 5

ROTFLMAO

The Alamo Flag

The Mexican constitution of 1824 gave the people of Texas rights similar to those enjoyed at the time by the citizens of the United States, but every new Mexican government attempted to increase control over Texas. To call attention to this, Texans removed the coat of arms from the center of a Mexican flag, and replaced it with the date of the constitution. It was this banner that flew from the walls of the Alamo.

The USS Enterprise (NCC-1701) was constructed at the San Francisco Starship Yards and commissioned in the year 2245. This Constitution-class starship was first commanded by Captain Robert April, followed by Captain Christopher Pike, and finally Captain James T. Kirk.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.